Factorial

| n | n! |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 6 |

| 4 | 24 |

| 5 | 120 |

| 6 | 720 |

| 7 | 5040 |

| 8 | 40320 |

| 9 | 362880 |

| 10 | 3628800 |

| 11 | 39916800 |

| 12 | 479001600 |

| 13 | 6227020800 |

| 14 | 87178291200 |

| 15 | 1307674368000 |

| 16 | 20922789888000 |

| 17 | 355687428096000 |

| 18 | 6402373705728000 |

| 19 | 121645100408832000 |

| 20 | 2432902008176640000 |

| 25 | 1.551121004×1025 |

| 50 | 3.041409320×1064 |

| 70 | 1.197857167×10100 |

| 100 | 9.332621544×10157 |

| 450 | 1.733368733×101000 |

| 1000 | 4.023872601×102567 |

| 3249 | 6.412337688×1010000 |

| 10000 | 2.846259681×1035659 |

| 25206 | 1.205703438×10100000 |

| 100000 | 2.824229408×10456573 |

| 205023 | 2.503898932×101000004 |

| 1000000 | 8.263931688×105565708 |

| 1723508 | 5.290070307×1010000001 |

| 2000000 | 3.776821058×1011733474 |

| 10000000 | 1.202423401×1065657059 |

| 14842907 | 2.788662975×10100000000 |

| 10100 | 109.956570552×10101 |

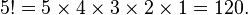

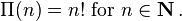

In mathematics, the factorial of a non-negative integer n, denoted by n!, is the product of all positive integers less than or equal to n. For example,

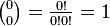

The value of 0! is 1, according to the convention for an empty product.[1]

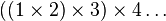

The factorial operation is encountered in many areas of mathematics, notably in combinatorics, algebra, and mathematical analysis. Its most basic occurrence is the fact that there are n! ways to arrange n distinct objects into a sequence (i.e., permutations of the set of objects). This fact was known at least as early as the 12th century, to Indian scholars.[2] Fabian Stedman in 1677 described factorials as applied to change ringing.[3] After describing a recursive approach, Stedman gives a statement of a factorial (using the language of the original):

Now the nature of these methods is such, that the changes on one number comprehends [includes] the changes on all lesser numbers, ... insomuch that a compleat Peal of changes on one number seemeth to be formed by uniting of the compleat Peals on all lesser numbers into one entire body;[4]

The notation n! was introduced by Christian Kramp in 1808.[5]

The definition of the factorial function can also be extended to non-integer arguments, while retaining its most important properties; this involves more advanced mathematics, notably techniques from mathematical analysis.

Definition

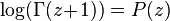

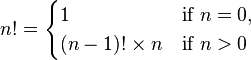

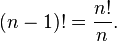

The factorial function is formally defined by the product

or by the recurrence relation

The factorial function can also be defined by using the power rule as

All of the above definitions incorporate the instance

in the first case by the convention that the product of no numbers at all is 1. This is convenient because:

- There is exactly one permutation of zero objects (with nothing to permute, "everything" is left in place).

- The recurrence relation (n + 1)! = n! × (n + 1), valid for n > 0, extends to n = 0.

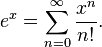

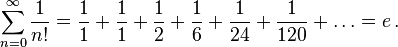

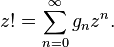

- It allows for the expression of many formulae, such as the exponential function, as a power series:

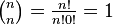

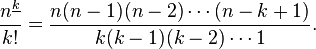

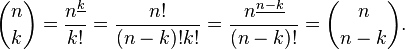

- It makes many identities in combinatorics valid for all applicable sizes. The number of ways to choose 0 elements from the empty set is

. More generally, the number of ways to choose (all) n elements among a set of n is

. More generally, the number of ways to choose (all) n elements among a set of n is  .

.

The factorial function can also be defined for non-integer values using more advanced mathematics, detailed in the section below. This more generalized definition is used by advanced calculators and mathematical software such as Maple or Mathematica.

Applications

Although the factorial function has its roots in combinatorics, formulas involving factorials occur in many areas of mathematics.

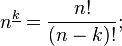

- There are n! different ways of arranging n distinct objects into a sequence, the permutations of those objects.

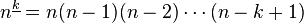

- Often factorials appear in the denominator of a formula to account for the fact that ordering is to be ignored. A classical example is counting k-combinations (subsets of k elements) from a set with n elements. One can obtain such a combination by choosing a k-permutation: successively selecting and removing an element of the set, k times, for a total of

- possibilities. This however produces the k-combinations in a particular order that one wishes to ignore; since each k-combination is obtained in k! different ways, the correct number of k-combinations is

- This number is known as the binomial coefficient

, because it is also the coefficient of Xk in (1 + X)n.

, because it is also the coefficient of Xk in (1 + X)n.

- Factorials occur in algebra for various reasons, such as via the already mentioned coefficients of the binomial formula, or through averaging over permutations for symmetrization of certain operations.

- Factorials also turn up in calculus; for example they occur in the denominators of the terms of Taylor's formula, where they are used as compensation terms due to the n-th derivative of xn being equivalent to n!.

- Factorials are also used extensively in probability theory.

- Factorials can be useful to facilitate expression manipulation. For instance the number of k-permutations of n can be written as

- while this is inefficient as a means to compute that number, it may serve to prove a symmetry property of binomial coefficients:

Number theory

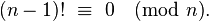

Factorials have many applications in number theory. In particular, n! is necessarily divisible by all prime numbers up to and including n. As a consequence, n > 5 is a composite number if and only if

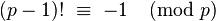

A stronger result is Wilson's theorem, which states that

if and only if p is prime.

Legendre's formula gives the multiplicity of the prime p occurring in the prime factorization of  as

as

or, equivalently,

where  denotes the sum of the standard base-p digits of n.

denotes the sum of the standard base-p digits of n.

The only factorial that is also a prime number is 2, but there are many primes of the form n! ± 1, called factorial primes.

All factorials greater than 1! are even, as they are all multiples of 2. Also, all factorials from 5! upwards are multiples of 10 (and hence have a trailing zero as their final digit), because they are multiples of 5 and 2.

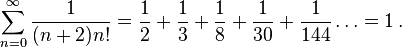

Series of reciprocals

The reciprocals of factorials produce a convergent series: (see e)

Although the sum of this series is an irrational number, it is possible to multiply the factorials by positive integers to produce a convergent series with a rational sum:

The convergence of this series to 1 can be seen from the fact that its partial sums are less than one by an inverse factorial. Therefore, the factorials do not form an irrationality sequence.[7]

Rate of growth and approximations for large n

As n grows, the factorial n! increases faster than all polynomials and exponential functions (but slower than double exponential functions) in n.

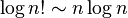

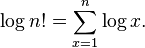

Most approximations for n! are based on approximating its natural logarithm

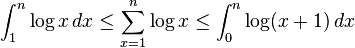

The graph of the function f(n) = log n! is shown in the figure on the right. It looks approximately linear for all reasonable values of n, but this intuition is false. We get one of the simplest approximations for log n! by bounding the sum with an integral from above and below as follows:

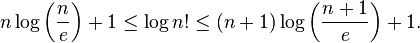

which gives us the estimate

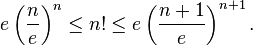

Hence  (see Big O notation). This result plays a key role in the analysis of the computational complexity of sorting algorithms (see comparison sort). From the bounds on log n! deduced above we get that

(see Big O notation). This result plays a key role in the analysis of the computational complexity of sorting algorithms (see comparison sort). From the bounds on log n! deduced above we get that

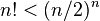

It is sometimes practical to use weaker but simpler estimates. Using the above formula it is easily shown that for all n we have  , and for all n ≥ 6 we have

, and for all n ≥ 6 we have  .

.

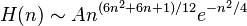

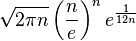

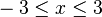

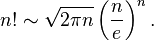

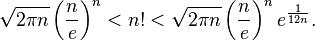

For large n we get a better estimate for the number n! using Stirling's approximation:

This in fact comes from an asymptotic series for the logarithm, and n factorial lies between this and the next approximation:

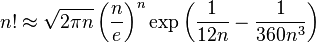

Another approximation for log n! is given by Srinivasa Ramanujan (Ramanujan 1988)

or

Both this and  give a relative error on the order of 1/n3, but Ramanujan's is about four times more accurate. However, if we use two correction terms (as in Ramanujan's approximation) the relative error will be of order 1/n5:

give a relative error on the order of 1/n3, but Ramanujan's is about four times more accurate. However, if we use two correction terms (as in Ramanujan's approximation) the relative error will be of order 1/n5:

Computation

If efficiency is not a concern, computing factorials is trivial from an algorithmic point of view: successively multiplying a variable initialized to 1 by the integers 2 up to n (if any) will compute n!, provided the result fits in the variable. In functional languages, the recursive definition is often implemented directly to illustrate recursive functions.

The main practical difficulty in computing factorials is the size of the result. To assure that the exact result will fit for all legal values of even the smallest commonly used integral type (8-bit signed integers) would require more than 700 bits, so no reasonable specification of a factorial function using fixed-size types can avoid questions of overflow. The values 12! and 20! are the largest factorials that can be stored in, respectively, the 32-bit and 64-bit integers commonly used in personal computers. Floating-point representation of an approximated result allows going a bit further, but this also remains quite limited by possible overflow. Most calculators use scientific notation with 2-digit decimal exponents, and the largest factorial that fits is then 69!, because 69! < 10100 < 70!. Other implementations (e.g., computer software such as spreadsheet programs) can often handle larger values.

Most software applications will compute small factorials by direct multiplication or table lookup. Larger factorial values can be approximated using Stirling's formula. Wolfram Alpha can calculate exact results for the ceiling function and floor function applied to the binary, natural and common logarithm of n! for values of n up to 249999, and up to 20,000,000! for the integers.

If the exact values of large factorials are needed, they can be computed using arbitrary-precision arithmetic. Instead of doing the sequential multiplications  , a program can partition the sequence into two parts, whose products are roughly the same size, and multiply them using a divide-and-conquer method. This is often more efficient.[8]

, a program can partition the sequence into two parts, whose products are roughly the same size, and multiply them using a divide-and-conquer method. This is often more efficient.[8]

The asymptotically best efficiency is obtained by computing n! from its prime factorization. As documented by Peter Borwein, prime factorization allows n! to be computed in time O(n(log n log log n)2), provided that a fast multiplication algorithm is used (for example, the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm).[9] Peter Luschny presents source code and benchmarks for several efficient factorial algorithms, with or without the use of a prime sieve.[10]

Extension of factorial to non-integer values of argument

The Gamma and Pi functions

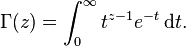

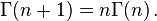

Besides nonnegative integers, the factorial function can also be defined for non-integer values, but this requires more advanced tools from mathematical analysis. One function that "fills in" the values of the factorial (but with a shift of 1 in the argument) is called the Gamma function, denoted Γ(z), defined for all complex numbers z except the non-positive integers, and given when the real part of z is positive by

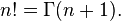

Its relation to the factorials is that for any natural number n

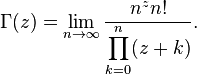

Euler's original formula for the Gamma function was

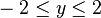

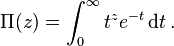

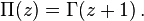

An alternative notation, originally introduced by Gauss, is sometimes used. The Pi function, denoted Π(z) for real numbers z no less than 0, is defined by

In terms of the Gamma function it is

It truly extends the factorial in that

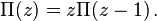

In addition to this, the Pi function satisfies the same recurrence as factorials do, but at every complex value z where it is defined

In fact, this is no longer a recurrence relation but a functional equation. Expressed in terms of the Gamma function this functional equation takes the form

Since the factorial is extended by the Pi function, for every complex value z where it is defined, we can write:

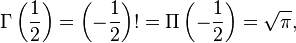

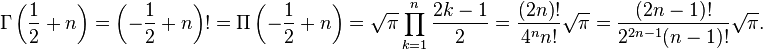

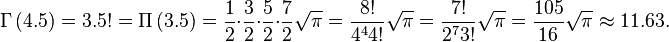

The values of these functions at half-integer values is therefore determined by a single one of them; one has

from which it follows that for n ∈ N,

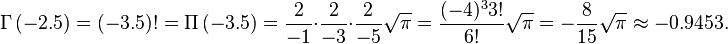

For example,

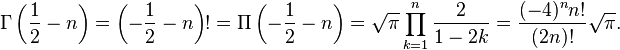

It also follows that for n ∈ N,

For example,

The Pi function is certainly not the only way to extend factorials to a function defined at almost all complex values, and not even the only one that is analytic wherever it is defined. Nonetheless it is usually considered the most natural way to extend the values of the factorials to a complex function. For instance, the Bohr–Mollerup theorem states that the Gamma function is the only function that takes the value 1 at 1, satisfies the functional equation Γ(n + 1) = nΓ(n), is meromorphic on the complex numbers, and is log-convex on the positive real axis. A similar statement holds for the Pi function as well, using the Π(n) = nΠ(n − 1) functional equation.

However, there exist complex functions that are probably simpler in the sense of analytic function theory and which interpolate the factorial values. For example, Hadamard's 'Gamma'-function (Hadamard 1894) which, unlike the Gamma function, is an entire function.[11]

Euler also developed a convergent product approximation for the non-integer factorials, which can be seen to be equivalent to the formula for the Gamma function above:

However, this formula does not provide a practical means of computing the Pi or Gamma function, as its rate of convergence is slow.

Applications of the Gamma function

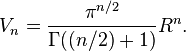

The volume of an n-dimensional hypersphere of radius R is

Factorial at the complex plane

Representation through the Gamma-function allows evaluation of factorial of complex argument. Equilines of amplitude and phase of factorial are shown in figure. Let  . Several levels of constant modulus (amplitude)

. Several levels of constant modulus (amplitude)  and constant phase

and constant phase  are shown. The grid covers range

are shown. The grid covers range

,

,

with unit step. The scratched line shows the level

with unit step. The scratched line shows the level  .

.

Thin lines show intermediate levels of constant modulus and constant phase. At poles  , phase and amplitude are not defined. Equilines are dense in vicinity of singularities along negative integer values of the argument.

, phase and amplitude are not defined. Equilines are dense in vicinity of singularities along negative integer values of the argument.

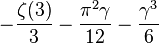

For  , the Taylor expansions can be used:

, the Taylor expansions can be used:

The first coefficients of this expansion are

|

|

approximation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 |  |

|

| 1 |  |

|

| 2 |  |

|

| 3 |  |

|

where  is the Euler constant and

is the Euler constant and  is the Riemann zeta function. Computer algebra systems such as Sage can generate many terms of this expansion.

is the Riemann zeta function. Computer algebra systems such as Sage can generate many terms of this expansion.

Approximations of factorial

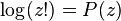

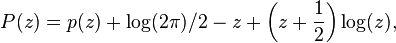

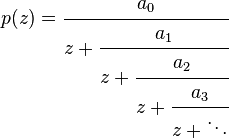

For the large values of the argument, factorial can be approximated through the integral of the digamma function, using the continued fraction representation. This approach is due to T. J. Stieltjes (1894). Writing z! = exp(P(z)) where P(z) is

Stieltjes gave a continued fraction for p(z)

The first few coefficients an are[12]

| n | an |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 / 12 |

| 1 | 1 / 30 |

| 2 | 53 / 210 |

| 3 | 195 / 371 |

| 4 | 22999 / 22737 |

| 5 | 29944523 / 19733142 |

| 6 | 109535241009 / 48264275462 |

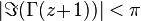

There is a misconception that  or

or  for any complex z ≠ 0. Indeed, the relation through the logarithm is valid only for specific range of values of z in vicinity of the real axis, while

for any complex z ≠ 0. Indeed, the relation through the logarithm is valid only for specific range of values of z in vicinity of the real axis, while  . The larger is the real part of the argument, the smaller should be the imaginary part. However, the inverse relation, z! = exp(P(z)), is valid for the whole complex plane apart from zero. The convergence is poor in vicinity of the negative part of the real axis. (It is difficult to have good convergence of any approximation in vicinity of the singularities). While

. The larger is the real part of the argument, the smaller should be the imaginary part. However, the inverse relation, z! = exp(P(z)), is valid for the whole complex plane apart from zero. The convergence is poor in vicinity of the negative part of the real axis. (It is difficult to have good convergence of any approximation in vicinity of the singularities). While  or

or  , the 6 coefficients above are sufficient for the evaluation of the factorial with the complex<double> precision. For higher precision more coefficients can be computed by a rational QD-scheme (H. Rutishauser's QD algorithm).[13]

, the 6 coefficients above are sufficient for the evaluation of the factorial with the complex<double> precision. For higher precision more coefficients can be computed by a rational QD-scheme (H. Rutishauser's QD algorithm).[13]

Non-extendability to negative integers

The relation n! = n × (n − 1)! allows one to compute the factorial for an integer given the factorial for a smaller integer. The relation can be inverted so that one can compute the factorial for an integer given the factorial for a larger integer:

Note, however, that this recursion does not permit us to compute the factorial of a negative integer; use of the formula to compute (−1)! would require a division by zero, and thus blocks us from computing a factorial value for every negative integer. (Similarly, the Gamma function is not defined for non-positive integers, though it is defined for all other complex numbers.)

Factorial-like products and functions

There are several other integer sequences similar to the factorial that are used in mathematics:

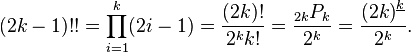

Double factorial

The product of all the odd integers up to some odd positive integer n is called the double factorial of n, and denoted by n!!.[14] That is,

For example, 9!! = 1 × 3 × 5 × 7 × 9 = 945.

The sequence of double factorials for n = 1, 3, 5, 7, ... starts as

Double factorial notation may be used to simplify the expression of certain trigonometric integrals,[15] to provide an expression for the values of the Gamma function at half-integer arguments and the volume of hyperspheres,[16] and to solve many counting problems in combinatorics including counting binary trees with labeled leaves and perfect matchings in complete graphs.[14][17]

Multifactorials

A common related notation is to use multiple exclamation points to denote a multifactorial, the product of integers in steps of two ( ), three (

), three ( ), or more. The double factorial is the most commonly used variant, but one can similarly define the triple factorial (

), or more. The double factorial is the most commonly used variant, but one can similarly define the triple factorial ( ) and so on. One can define the k-th factorial, denoted by

) and so on. One can define the k-th factorial, denoted by  , recursively for positive integers as

, recursively for positive integers as

though see the alternative definition below. In addition, similarly to 0! = 1!/1 = 1, one can define:

Some mathematicians have suggested an alternative notation of  for the double factorial and similarly

for the double factorial and similarly  for other multifactorials, but this has not come into general use.

for other multifactorials, but this has not come into general use.

In the same way that  is not defined for negative integers, and

is not defined for negative integers, and  is not defined for negative even integers,

is not defined for negative even integers,  is not defined for negative integers divisible by

is not defined for negative integers divisible by  .

.

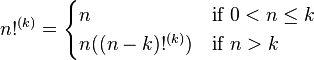

Alternative extension of the multifactorial

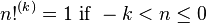

Alternatively, the multifactorial z!(k) can be extended to most real and complex numbers z by noting that when z is one more than a positive multiple of k then

This last expression is defined much more broadly than the original; with this definition, z!(k) is defined for all complex numbers except the negative real numbers evenly divisible by k. This definition is consistent with the earlier definition only for those integers z satisfying z ≡ 1 mod k.

In addition to extending z!(k) to most complex numbers z, this definition has the feature of working for all positive real values of k. Furthermore, when k = 1, this definition is mathematically equivalent to the Π(z) function, described above. Also, when k = 2, this definition is mathematically equivalent to the alternative extension of the double factorial.

Primorial

The primorial (sequence A002110 in OEIS) is similar to the factorial, but with the product taken only over the prime numbers.

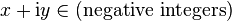

Quadruple factorial

Contrary to consistency with the above definition of the term double factorial, the quadruple factorial is not the multifactorial n!(4); it is a much larger number given by (2n)!/n!, starting as

It is also equal to

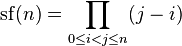

Superfactorial

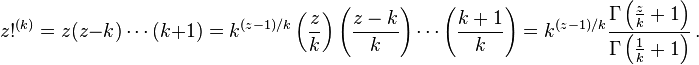

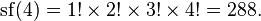

Neil Sloane and Simon Plouffe defined a superfactorial in The Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (Academic Press, 1995) to be the product of the first  factorials. So the superfactorial of 4 is

factorials. So the superfactorial of 4 is

In general

Equivalently, the superfactorial is given by the formula

which is the determinant of a Vandermonde matrix.

The sequence of superfactorials starts (from  ) as

) as

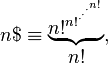

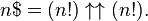

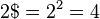

Alternative definition

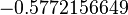

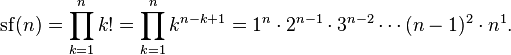

Clifford Pickover in his 1995 book Keys to Infinity used a new notation, n$, to define the superfactorial

or as,

where the [4] notation denotes the hyper4 operator, or using Knuth's up-arrow notation,

This sequence of superfactorials starts:

Here, as is usual for compound exponentiation, the grouping is understood to be from right to left:

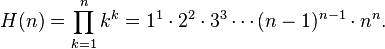

Hyperfactorial

Occasionally the hyperfactorial of n is considered. It is written as H(n) and defined by

For n = 1, 2, 3, 4, ... the values H(n) are 1, 4, 108, 27648,... (sequence A002109 in OEIS).

The asymptotic growth rate is

where A = 1.2824... is the Glaisher–Kinkelin constant.[18] H(14) = 1.8474...×1099 is already almost equal to a googol, and H(15) = 8.0896...×10116 is almost of the same magnitude as the Shannon number, the theoretical number of possible chess games. Compared to the Pickover definition of the superfactorial, the hyperfactorial grows relatively slowly.

The hyperfactorial function can be generalized to complex numbers in a similar way as the factorial function. The resulting function is called the K-function.

See also

- Alternating factorial

- Bhargava factorial

- Digamma function

- Exponential factorial

- Factorial number system

- Factorial prime

- Factorion

- List of factorial and binomial topics

- Pochhammer symbol, which gives the falling or rising factorial

- Subfactorial

- Trailing zeros of factorial

- Triangular number, the additive analogue of factorial

Notes

- ↑ Ronald L. Graham, Donald E. Knuth, Oren Patashnik (1988) Concrete Mathematics, Addison-Wesley, Reading MA. ISBN 0-201-14236-8, p. 111

- ↑ N. L. Biggs, The roots of combinatorics, Historia Math. 6 (1979) 109−136

- ↑ Stedman, Fabian (1677), Campanalogia, London, pp. 6–9 The publisher is given as "W.S." who may have been William Smith, possibly acting as agent for the Society of College Youths, to which society the "Dedicatory" is addressed.

- ↑ Stedman 1677, p. 8.

- ↑ Higgins, Peter (2008), Number Story: From Counting to Cryptography, New York: Copernicus, p. 12, ISBN 978-1-84800-000-1 says Krempe though.

- ↑ http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mathematics/18-01-single-variable-calculus-fall-2006/lecture-notes/lec4.pdf

- ↑ Guy, Richard K. (2004), "E24 Irrationality sequences", Unsolved problems in number theory (3rd ed.), Springer-Verlag, p. 346, ISBN 0-387-20860-7, Zbl 1058.11001.

- ↑ GNU MP software manual, "Factorial Algorithm" (retrieved 22 January 2013).

- ↑ Peter Borwein. "On the Complexity of Calculating Factorials". Journal of Algorithms 6, 376–380 (1985)

- ↑ Peter Luschny, Fast-Factorial-Functions: The Homepage of Factorial Algorithms.

- ↑ Peter Luschny, Hadamard versus Euler - Who found the better Gamma function?.

- ↑ Digital Library of Mathematical Functions, http://dlmf.nist.gov/5.10

- ↑ Peter Luschny, On Stieltjes' Continued Fraction for the Gamma Function..

- 1 2 Callan, David (2009), A combinatorial survey of identities for the double factorial, arXiv:0906.1317.

- ↑ Meserve, B. E. (1948), "Classroom Notes: Double Factorials", The American Mathematical Monthly 55 (7): 425–426, doi:10.2307/2306136, MR 1527019

- ↑ Mezey, Paul G. (2009), "Some dimension problems in molecular databases", Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 45 (1): 1–6, doi:10.1007/s10910-008-9365-8.

- ↑ Dale, M. R. T.; Moon, J. W. (1993), "The permuted analogues of three Catalan sets", Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 34 (1): 75–87, doi:10.1016/0378-3758(93)90035-5, MR 1209991.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Glaisher–Kinkelin Constant", MathWorld.

References

- Hadamard, M. J. (1894), Sur L’Expression Du Produit 1·2·3· · · · ·(n−1) Par Une Fonction Entière (PDF) (in French), OEuvres de Jacques Hadamard, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifiques, Paris, 1968

- Ramanujan, Srinivasa (1988), The lost notebook and other unpublished papers, Springer Berlin, p. 339, ISBN 3-540-18726-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Factorial (function). |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Factorial", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Factorial", MathWorld.

- Factorial at PlanetMath.org.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![n!\approx\sqrt{2\pi n}\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^n[1 +1/(2n) +1/(8n^2)]^{1/6}.](../I/m/4705e168ff6abcc86e5792abaa395dc7.png)

![\begin{align}n! = \Pi(n) &= \prod_{k = 1}^\infty \left(\frac{k+1}{k}\right)^n\!\!\frac{k}{n+k} \\ &= \left[ \left(\frac{2}{1}\right)^n\frac{1}{n+1}\right]\left[ \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^n\frac{2}{n+2}\right]\left[ \left(\frac{4}{3}\right)^n\frac{3}{n+3}\right]\cdots. \end{align}](../I/m/10c77ce080c89f41a96c55dc07d4f0ce.png)

![\begin{align}

2^n\frac{(2n)!}{n!2^n} & = 2^n \frac{(2\cdot 4\cdots 2n) (1\cdot 3\cdots (2n-1))}{2\cdot 4\cdots 2n} \\[8pt]

& = (1\cdot 2)\cdot (3 \cdot 2) \cdots((2n-1)\cdot 2)=(4n-2)!^{(4)}.

\end{align}](../I/m/c31a3285be1fd9627df892969d3464a1.png)

![n\$=n! [4] n! \,](../I/m/86a3b984b90c6ab58a76f345c932f904.png)

![3\$=6 [4] 6={^6}6=6^{6^{6^{6^{6^6}}}}.](../I/m/240b1d0dab333c3d993d386c6db8df61.png)