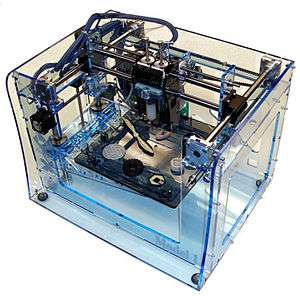

Fab@Home

Fab@Home was the first multi-material 3D printer available to the public, and one of the first two open-source DIY 3D printers (the other one being the RepRap). Up until 2005, all 3D printers were industrial scale, expensive and proprietary. The high cost and closed nature of the 3D printing industry at the time limited the accessibility of the technology to the masses, the range of materials that could be used and the level of exploration that could be done by end-users. The goal of the Fab@Home project was to change this situation by creating a versatile, low-cost, open and “hackable” printer to accelerate technology innovation and its migration into the consumer and Maker space.

Since its open-source release in 2006,[1] hundreds of Fab@Home 3D printers were built across the world,[2] and its design elements could be found in many later DIY printers, most notably the Makerbot Replicator. The printer’s multiple syringe-based deposition method allowed for some of the first multi-material prints including direct fabrication of active batteries, actuators, and sensors, as well as esoteric materials for bioprinting and food printing.[3] The project was closed in 2012 when it was clear that the project’s goal was achieved and distribution of DIY and consumer printers outpaced the sales of industrial printers for the first time.[3]

History

The project was led by students at Cornell University's department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering. The effort was inspired by the history of the Altair 8800, one of the first DIY home computer kits released in 1975. The Altair 8800 is largely credited with triggering the home computing revolution and the transition from the industrial mainframe to the consumer desktop, by making a low-cost, open and “hackable” computer accessible to home enthusiasts for the first time. The goal of the Fab@Home project was to accomplish a similar effect in the 3D printing space. The project was one of the first larger scale cases that applied the open source development model to physical devices, a process that later became known as Open Source Hardware.

Early versions of the device were produced and refined in the lab. The first official release of the Fab@Home model 1 coincided with a presentation at the Solid Freeform Fabrication conference in 2006.[1] After its first release, undergraduate and graduate students at Cornell and other locations joined the team and developed an improved version, later released as the Fab@Home Model 2.[4] The main improvements included easier assembly, no soldering, and fewer parts. The team then expanded and developed the model 3. One important variation of Fab@Home was the Fab@School project, which explored the use of 3D printers suitable for classroom use in elementary grades. Fab@School printers could print with benign materials such as Play-Doh and included a safety enclosure.

The project received wide media attention in its initial years, bringing 3D printing from a relatively obscure technology to broader attention. Notable recognition was the Popular Mechanics Breakthrough award[5] and the Rapid Prototyping Journal best paper of the year award.

Technical abilities

The Fab@Home is a syringe-based deposition system. An X-Y-Z gantry system moves a syringe pump across a 20×20×20 cm (7.87x7.87x7.87 inch) build volume at a maximum speed of 10 mm/s and resolution of 25 µm. Multiple syringes can be controlled independently to deposit material through syringe tips. The syringe displacement could be controlled with microliter precision.

The first version of Fab@Home print head had two syringes; later version had more syringes, up to one print head that had eight syringes that could be used simultaneously.

One of the key advantages of using a syringe based deposition method was that a broad range of materials could be deposited, essentially any liquid, paste, gel or slurry that could be squeezed through a syringe tip. That versatility allowed going beyond printing just in thermoplastics, as did the RepRap and most consumer-scale 3D printers that followed. The range of materials that could be printed with a Fab@Home included hard materials such as epoxy, elastomers such as silicone, biological materials such as cell-seeded hydrogels, food materials such as chocolate, cookie dough and cheese, engineering materials such as stainless steel (later sintered in an oven), and active materials such as conductive wires and magnets. The stated technical goal of the project was to print a complete active system, going beyond printing just passive parts. The project succeeded in printing active devices such as batteries, actuators, sensors, and even a working telegraph machine.

Project members

- Founders: Evan Malone and Hod Lipson

- Project leads: Evan Malone (2005-2009), Daniel Cohen (2010), Jeffery Lipton (2011-2012)

- Project team members (in no particular order): Dan Periard, Max Lobovsky, James Smith, Michael Heinz, Warren Parad, Garrett Bernstien, Tianyou Li, Justin Quartiere, Daniel Sheiner, Kamaal Washington, Abdul-Aziz Umaru, Rian Masanoff, Justin Granstein, Jordan Whitney, Scott Lichtenthal, Karl Gluck

See also

- The RepRap project

References

- 1 2 Malone E., Lipson H., (2006) Fab@Home: The Personal Desktop Fabricator Kit, Proceedings of the 17th Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin TX, Aug 2006

- ↑ Additive Manufacturing and 3D Printing State of the Industry, 2012 Annual Worldwide Progress Report, ISBN 0-9754429-8-8

- 1 2 Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman, Fabricated: The new World of 3D printing, Wiley Press, 2013

- ↑ Lipton, J. Cohen,D., Heinz,M., Lobovsky, M., Parad,W., Bernstien, G., Li,T., Quartiere,J., Washington,K., Umaru,A., Masanoff,R., Granstein, J., Whitney,J., Lipson,H., (2009) "Fab@Home Model 2: Towards Ubiquitous Personal Fabrication Devices" Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium (SFF'09), Aug 3-5 2009, Austin, TX, USA.

- ↑ 2007 Popular Mechanics Breakthrough Award, Fab at Home, Open-Source 3D Printer, Lets Users Make Anything