Fine-needle aspiration

| Fine-needle aspiration | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |

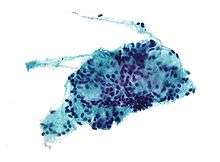

Micrograph of a needle aspiration biopsy specimen of a salivary gland showing adenoid cystic carcinoma. Pap stain. | |

| MeSH | D044963 |

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB, FNA or NAB), or fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), is a diagnostic procedure used to investigate superficial (just under the skin) lumps or masses. In this technique, a thin, hollow needle is inserted into the mass for sampling of cells that, after being stained, will be examined under a microscope. There could be cytology exam of aspirate (cell specimen evaluation, FNAC) or histological (biopsy - tissue specimen evaluation, FNAB).[1] Fine-needle aspiration biopsies are very safe, minor surgical procedures. Often, a major surgical (excisional or open) biopsy can be avoided by performing a needle aspiration biopsy instead. In 1981, the first fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the United States was done at Maimonides Medical Center, eliminating the need for surgery and hospitalization. Today, this procedure is widely used in the diagnosis of cancer and inflammatory conditions.[2]

A needle aspiration biopsy is safer and less traumatic than an open surgical biopsy, and significant complications are usually rare, depending on the body site. Common complications include bruising and soreness. There is a risk, because the biopsy is very small (only a few cells), that the problematic cells will be missed, resulting in a false negative result. There is also a risk that the cells taken will not enable a definitive diagnosis.

Applications

This type of sampling is performed for one of two reasons:

- A biopsy is performed on a lump or a tissue mass when its nature is in question.

- For known tumors, this biopsy is performed to assess the effect of treatment or to obtain tissue for special studies.

When the lump can be felt, the biopsy is usually performed by a cytopathologist or a surgeon. In this case, the procedure is usually short and simple. Otherwise, it may be performed by an interventional radiologist, a doctor with training in performing such biopsies under x-ray or ultrasound guidance. In this case, the procedure may require more extensive preparation and take more time to perform.

Also, fine-needle aspiration is the main method used for chorionic villus sampling,[3] as well as for many types of body fluid sampling.

It is also used for ultrasound-guided aspiration of breast abscess,[4] of breast cysts, and of seromas.[5]

Preparation

Several preparations may be necessary before this procedure.

- No use of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (e.g. ibuprofen, naproxen) for one week before the procedure;

- No food intake a few hours before the procedure;

- Routine blood tests (including clotting profile) must be completed two weeks before the biopsy;

- Suspension of blood anticoagulant medications;

- Antibiotic prophylaxis may be instituted.

Before the procedure is started, vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature, etc.) may be taken. Then, depending on the nature of the biopsy, an intravenous line may be placed. Very anxious patients may want to be given sedation through this line. For patients with less anxiety, oral medication (Valium) can be prescribed to be taken before the procedure.

Procedure

The skin above the area to be biopsied is swabbed with an antiseptic solution and draped with sterile surgical towels. The skin, underlying fat, and muscle may be numbed with a local anesthetic, although this is often not necessary with superficial masses. After locating the mass for biopsy, using x-rays or palpation, a special needle of very fine diameter is passed into the mass. The needle may be inserted and withdrawn several times. There are many reasons for this:

- One needle may be used as a guide, with the other needles placed along it to achieve a more precise position.

- Sometimes, several passes may be needed to obtain enough cells for the intricate tests which the cytopathologists perform.

After the needles are placed into the mass, cells are withdrawn by aspiration with a syringe and spread on a glass slide. The patient's vital signs are taken again, and the patient is removed to an observation area for about 3 to 5 hours.

- For biopsies in the breast, ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy is the most common.

Post-operative care and complications

_(322383635).jpg)

As with any surgical procedure, complications are possible, but major complications due to thin needle aspiration biopsies are fairly uncommon, and when complications do occur, they are generally mild. The kind and severity of complications depend on the organs from which a biopsy is taken or the organs gone through to obtain cells.

After the procedure, mild analgesics are used to control post-operative pain. Aspirin or aspirin substitutes should not be taken for 48 hours after the procedure (unless aspirin is prescribed for a cardiac or neurological condition). Since sterility is maintained throughout the procedure, infection is rare. But should an infection occur, it will be treated with antibiotics. Bleeding is the most common complication of this procedure. A slight bruise may also appear. If a lung or kidney biopsy has been performed, it is very common to see a small amount of blood in sputum or urine after the procedure. Only a small amount of bleeding should occur. During the observation period after the procedure, bleeding should decrease over time. If more bleeding occurs, this will be monitored until it subsides. Rarely, major surgery will be necessary to stop the bleeding.

Other complications depend upon the body part on which the biopsy takes place:

- Lung biopsies are frequently complicated by pneumothorax (collapsed lung). This complication can also accompany biopsies in the upper abdomen near the base of the lung. About one-quarter to one-half of patients having lung biopsies will develop pneumothorax. Usually, the degree of collapse is small and resolves on its own without treatment. A small percentage of patients will develop a pneumothorax serious enough to require hospitalization and placement of a chest tube for treatment. Although it is impossible to predict in whom this will occur, collapsed lungs are more frequent and more serious in patients with severe emphysema and in patients in whom the biopsy is difficult to perform.

- For biopsies of the liver, bile leakages may occur, but these are quite rare.

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) may occur after biopsies in the area around the pancreas.

- In biopsies in the area of the breast, bleeding and bruising may occur, less frequently also infection (rarely) or (very rarely, and only if performed near the chest wall) pneumothorax.

- Deaths have been reported from needle aspiration biopsies, but such outcomes are extremely rare.

Criticism

A recent study showed that in one case a needle biopsy of a liver tumor resulted in spread of the cancer along the path of the needle, and concluded that needle aspiration was dangerous and unnecessary. The conclusions drawn from this paper were strongly criticized subsequently.[6]

Current findings

A recent study introduced a technology that allows analysis of hundreds of proteins from minimally invasive fine-needle aspirates. The method capitalizes on DNA-barcoded antibody sensing, where barcodes can be photocleaved and digitally detected without any amplification steps. The method showed high reproducibility and achieved single-cell sensitivity. Other than profiling cancer cells, the method could also be used as a clinical tool to identify pathway responses to molecularly targeted drugs and to predict drug response in patient samples. [7]

References

- ↑ http://www.indepreviews.com/article/2011/vol-13-no-1/006-084-FINE-NEEDLE-ASPIRATION-CYTOLOGY-%28F-N-A-C%29.pdf

- ↑ http://www.maimonidesmed.org/Main/CultureofInnovation.aspx, First US Procedure

- ↑ Chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis: information for you from Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Date published: 01/06/2006

- ↑ Trop I, Dugas A, David J, El Khoury M, Boileau JF, Larouche N, Lalonde L (October 2011). "Breast abscesses: evidence-based algorithms for diagnosis, management, and follow-up". Radiographics : a Review Publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc (review) 31 (6): 1683–99. doi:10.1148/rg.316115521. PMID 21997989.

- ↑ Department of Pathology University of Massachusetts Medical School (Emeritus) Guido Majno Professor; Department of Pathology University of Massachusetts Medical School (Emerita) Isabelle Joris Associate Professor (12 August 2004). Cells, Tissues, and Disease : Principles of General Pathology: Principles of General Pathology. Oxford University Press. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-19-974892-1.

- ↑ "bmj.com". Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ↑ Ullal AV, Peterson V, Agasti SS, et al. (Jan 2014). "Cancer cell profiling by barcoding allows multiplexed protein analysis in fine-needle aspirates.". Sci Transl Med. 6 (219): 219. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3007361. PMC 4063286. PMID 24431113.

- Originally adapted from Preparing for a needle aspiration biopsy (634 KB). Public domain text of the National Institutes of Health Warren Magnuson Grant Clinical Center.

- Video showing ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy

External links

- Aspiration Biopsy, Fine-Needle at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Breast

- -462749619 at GPnotebook - "fine needle aspiration cytology (breast)"

Lung

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia 003860 - "Lung needle biopsy"

Neck

- ent/561 at eMedicine - "Fine-Needle Aspiration of Neck Masses"

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia 003899 - "Thyroid nodule fine needle aspirate"

Bone

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia 003658 - "Bone marrow aspiration"

- med/2971 at eMedicine - "Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy"

| ||||||||||||||