Canine tooth

| Canine tooth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | dentes canini |

| MeSH | A14.549.167.860.200 |

| TA | A05.1.03.005 |

| FMA | 55636 |

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dog teeth, fangs, or (in the case of those of the upper jaw) eye teeth, are relatively long, pointed teeth. However, they can appear more flattened, causing them to resemble incisors and leading them to be called incisiform. They developed and are used primarily for firmly holding food in order to tear it apart, and occasionally as weapons. They are often the largest teeth in a mammal's mouth. Most species that develop them normally have four per mammal, two in the upper jaw and two in the lower, separated within each jaw by its incisors; humans and dogs are examples. In most species, canines are the anterior-most teeth in the maxillary bone.

The four canines in humans are the two maxillary canines and the two mandibular canines.

Details

There are four canine teeth: two in the upper (maxillary) and two in the lower (mandibular) arch. A canine is placed laterally to each lateral incisor. They are larger and stronger than the incisors, and their roots sink deeply into the bones, and cause well-marked prominences upon the surface.

The crown is large and conical, very convex on its labial surface, a little hollowed and uneven on its lingual surface, and tapering to a blunted point or cusp, which projects beyond the level of the other teeth. The root is single, but longer and thicker than that of the incisors, conical in form, compressed laterally, and marked by a slight groove on each side. The lingual surface also presents two depressions on either side of the surface separated by a ridge in between; these depressions are known as mesial and distal lingual fossae.

In humans, the upper canine teeth (popularly called eye teeth, from their position under the eyes[2]) are larger and longer than the lower, and usually present a distinct basal ridge. Eruption typically occurs between the ages of eleven and twelve years.

From a facial aspect, maxillary canines are approximately one millimetre narrower than the central incisor. Their mesial aspects resemble the adjacent lateral incisors, while their distal aspects anticipate the first premolars. They are slightly darker and more yellow in color than the other anterior teeth. From a lingual aspect, they have well developed mesial and distal marginal ridges and a well-developed cingulum. A prominent lingual ridge divides the lingual aspect in half and creates the mesial and distal lingual fossae between the lingual ridge and the marginal ridges. From a proximal aspect, they resemble the incisors, but are more robust, especially in the cingulum region. Incisally, they are visibly asymmetrical, as the mesial incisal edge is slightly shorter than the distal incisal edge, which places the cusp slightly mesial to the long axis of the tooth. They are also thicker labiolingually than mesiodistally. Because of the disproportionate incisal edges, the contacts are also asymmetrical. Mesially, the contact sits at the junction of the incisal and middle third of the crown, while distally, the contact as more cervical, in the middle of the middle third of the crown.

The lower canine teeth are placed nearer the middle line than the upper, so that their summits correspond to the intervals between the upper canines and the lateral incisors. Eruption typically occurs between the ages of nine and ten years of age.

From a facial aspect, the mandibular canine is notably narrower mesiodistally than the maxillary one, even though the root may be just as long (and at times bifurcated). A distinctive feature is the nearly straight outline this tooth has compared to the maxillary canine which is slightly more bowed. As in the maxillary canine, the mesial incisal edge (or cusp ridge) is shorter than the distal side, however, the cusp is displaced slightly lingual relative to the cusp of the maxillary canine. Lingually, the surface of the tooth is much more smooth compared to the very pronounced surface of the maxillary canine, and the cingulum is noted as less developed.

Sexual dimorphism

With many species, the canine teeth in the upper or lower jaw, or in both, are much larger in the males than in the females, or are absent in females, except sometimes a hidden rudiment. Certain antelopes, the musk-deer, camel, horse, boar, various apes, seals, and the walrus, offer instances.[3]

In non-mammals

In non-mammals, teeth similar to canines may be termed "caniniform" ("canine-shaped") teeth.

Additional images

-

Mouth (oral cavity)

-

Left maxilla. Outer surface.

-

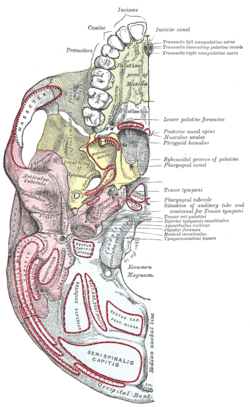

Base of skull. Inferior surface.

-

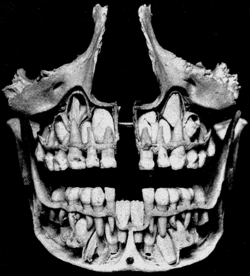

Unerupted permanent teeth underlie the deciduous teeth.

See also

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Berta, A. and Sumich, J. L. (1999). Marine mammals: evolutionary biology. San Diego, California: Academic Press. p. 494.

- ↑ "eye-tooth". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ↑ The Descent of Man. Charles Darwin. s:Descent of Man/Chapter XVII

External links

- Anatomy photo:34:os-0507 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||