Cohomology

In mathematics, specifically in homology theory and algebraic topology, cohomology is a general term for a sequence of abelian groups defined from a co-chain complex. That is, cohomology is defined as the abstract study of cochains, cocycles, and coboundaries. Cohomology can be viewed as a method of assigning algebraic invariants to a topological space that has a more refined algebraic structure than does homology. Cohomology arises from the algebraic dualization of the construction of homology. In less abstract language, cochains in the fundamental sense should assign 'quantities' to the chains of homology theory.

From its beginning in topology, this idea became a dominant method in the mathematics of the second half of the twentieth century; from the initial idea of homology as a topologically invariant relation on chains, the range of applications of homology and cohomology theories has spread out over geometry and abstract algebra. The terminology tends to mask the fact that in many applications cohomology, a contravariant theory, is more natural than homology. At a basic level this has to do with functions and pullbacks in geometric situations: given spaces X and Y, and some kind of function F on Y, for any mapping f : X → Y composition with f gives rise to a function F o f on X. Cohomology groups often also have a natural product, the cup product, which gives them a ring structure. Because of this feature, cohomology is a stronger invariant than homology, as it can differentiate between certain algebraic objects that homology cannot.

Definition

In algebraic topology, the cohomology groups for spaces can be defined as follows (see Hatcher).[1] Given a topological space X, consider the chain complex

as in the definition of singular homology (or simplicial homology). Here, the Cn are the free abelian groups generated by formal linear combinations of the singular n-simplices in X and ∂n is the nth boundary operator.

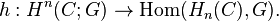

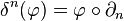

Now replace each Cn by its dual space C*n−1 = Hom(Cn, G), and ∂n by its transpose

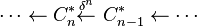

to obtain the cochain complex

Then the nth cohomology group with coefficients in G is defined to be Ker(δn+1)/Im(δn) and denoted by Hn(C; G). The elements of C*n are called singular n-cochains with coefficients in G , and the δn are referred to as the coboundary operators. Elements of Ker(δn+1), Im(δn) are called cocycles and coboundaries, respectively.

Note that the above definition can be adapted for general chain complexes, and not just the complexes used in singular homology. The study of general cohomology groups was a major motivation for the development of homological algebra, and has since found applications in a wide variety of settings (see below).

Given an element φ of C*n-1, it follows from the properties of the transpose that  as elements of C*n. We can use this fact to relate the cohomology and homology groups as follows. Every element φ of Ker(δn) has a kernel containing the image of ∂n. So we can restrict φ to Ker(∂n−1) and take the quotient by the image of ∂n to obtain an element h(φ) in Hom(Hn, G). If φ is also contained in the image of δn−1, then h(φ) is zero. So we can take the quotient by Ker(δn), and to obtain a homomorphism

as elements of C*n. We can use this fact to relate the cohomology and homology groups as follows. Every element φ of Ker(δn) has a kernel containing the image of ∂n. So we can restrict φ to Ker(∂n−1) and take the quotient by the image of ∂n to obtain an element h(φ) in Hom(Hn, G). If φ is also contained in the image of δn−1, then h(φ) is zero. So we can take the quotient by Ker(δn), and to obtain a homomorphism

It can be shown that this map h is surjective, and that we have a short split exact sequence

History

Although cohomology is fundamental to modern algebraic topology, its importance was not seen for some 40 years after the development of homology. The concept of dual cell structure, which Henri Poincaré used in his proof of his Poincaré duality theorem, contained the germ of the idea of cohomology, but this was not seen until later.

There were various precursors to cohomology. In the mid-1920s, J. W. Alexander and Solomon Lefschetz founded the intersection theory of cycles on manifolds. On an n-dimensional manifold M, a p-cycle and a q-cycle with nonempty intersection will, if in general position, have intersection a (p + q − n)-cycle. This enables us to define a multiplication of homology classes

- Hp(M) × Hq(M) → Hp+q−n(M).

Alexander had by 1930 defined a first cochain notion, based on a p-cochain on a space X having relevance to the small neighborhoods of the diagonal in Xp+1.

In 1931, Georges de Rham related homology and exterior differential forms, proving De Rham's theorem. This result is now understood to be more naturally interpreted in terms of cohomology.

In 1934, Lev Pontryagin proved the Pontryagin duality theorem; a result on topological groups. This (in rather special cases) provided an interpretation of Poincaré duality and Alexander duality in terms of group characters.

At a 1935 conference in Moscow, Andrey Kolmogorov and Alexander both introduced cohomology and tried to construct a cohomology product structure.

In 1936 Norman Steenrod published a paper constructing Čech cohomology by dualizing Čech homology.

From 1936 to 1938, Hassler Whitney and Eduard Čech developed the cup product (making cohomology into a graded ring) and cap product, and realized that Poincaré duality can be stated in terms of the cap product. Their theory was still limited to finite cell complexes.

In 1944, Samuel Eilenberg overcame the technical limitations, and gave the modern definition of singular homology and cohomology.

In 1945, Eilenberg and Steenrod stated the axioms defining a homology or cohomology theory. In their 1952 book, Foundations of Algebraic Topology, they proved that the existing homology and cohomology theories did indeed satisfy their axioms.[2]

In 1948 Edwin Spanier, building on work of Alexander and Kolmogorov, developed Alexander–Spanier cohomology.

Cohomology theories

Eilenberg–Steenrod theories

A cohomology theory is a family of contravariant functors from the category of pairs of topological spaces and continuous functions (or some subcategory thereof such as the category of CW complexes) to the category of Abelian groups and group homomorphisms that satisfies the Eilenberg–Steenrod axioms.

Some cohomology theories in this sense are:

Axioms and generalized cohomology theories

There are various ways to define cohomology groups (for example singular cohomology, Čech cohomology, Alexander–Spanier cohomology or Sheaf cohomology). These give different answers for some exotic spaces, but there is a large class of spaces on which they all agree. This is most easily understood axiomatically: there is a list of properties known as the Eilenberg–Steenrod axioms, and any two constructions that share those properties will agree at least on all finite CW complexes, for example.

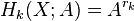

One of the axioms is the so-called dimension axiom: if P is a single point, then Hn(P) = 0 for all n ≠ 0, and H0(P) = Z. We can generalise slightly by allowing an arbitrary abelian group A in dimension zero, but still insisting that the groups in nonzero dimension are trivial. It turns out that there is again an essentially unique system of groups satisfying these axioms, which are denoted by  . In the common case where each group Hk(X) is isomorphic to Zrk for some rk in N, we just have

. In the common case where each group Hk(X) is isomorphic to Zrk for some rk in N, we just have  . In general, the relationship between Hk(X) and

. In general, the relationship between Hk(X) and  is only a little more complicated, and is again controlled by the Universal coefficient theorem.

is only a little more complicated, and is again controlled by the Universal coefficient theorem.

More significantly, we can drop the dimension axiom altogether. There are a number of different ways to define groups satisfying all the other axioms, including the following:

- The stable homotopy groups

- Various different flavours of cobordism groups:

and so on. The last of these (known as complex cobordism) is especially important, because of the link with formal group theory via a theorem of Daniel Quillen.

and so on. The last of these (known as complex cobordism) is especially important, because of the link with formal group theory via a theorem of Daniel Quillen. - Various different flavours of K-theory:

(real periodic K-theory),

(real periodic K-theory),  (real connective),

(real connective),  (complex periodic),

(complex periodic),  (complex connective) and so on.

(complex connective) and so on. - Brown–Peterson homology, Morava K-theory, Morava E-theory, and other theories defined using the algebra of formal groups.

- Various flavours of elliptic homology

These are called generalised homology theories; they carry much richer information than ordinary homology, but are often harder to compute. Their study is tightly linked (via the Brown representability theorem) to stable homotopy.

A cohomology theory E is said to be multiplicative if  is a graded ring.

is a graded ring.

Other cohomology theories

Theories in a broader sense of cohomology include:[3] [4]

- André–Quillen cohomology

- BRST cohomology

- Bonar–Claven cohomology

- Bounded cohomology

- Coherent cohomology

- Crystalline cohomology

- Cyclic cohomology

- Deligne cohomology

- Dirac cohomology

- Étale cohomology

- Flat cohomology

- Galois cohomology

- Gel'fand–Fuks cohomology

- Group cohomology

- Harrison cohomology

- Hochschild cohomology

- Intersection cohomology

- Khovanov homology

- Lie algebra cohomology

- Local cohomology

- Motivic cohomology

- Non-abelian cohomology

- Perverse cohomology

- Quantum cohomology

- Schur cohomology

- Spencer cohomology

- Topological André–Quillen cohomology

- Topological cyclic cohomology

- Topological Hochschild cohomology

- Γ cohomology

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Hatcher, Allen. Algebraic Topology. Cambridge U Press, 2001.

- ↑ Spanier, E. H. (2000) "Book reviews: Foundations of Algebraic Topology" Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 37(1): pp. 114–115

- ↑ http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http://www.geocities.com/jefferywinkler2/ktheory3.html&date=2009-10-26+00:45:56

- ↑ https://www.cs.duke.edu/courses/fall06/cps296.1/

References

- Hatcher, A. (2001) "Algebraic Topology", Cambridge U press, England: Cambridge, p. 198, ISBN 0-521-79160-X and ISBN 0-521-79540-0.

- Hazewinkel, M. (ed.), Encyclopaedia of Mathematics: An Updated and Annotated Translation of the Soviet "Mathematical Encyclopaedia"; Reidel, Dordrecht, Netherlands: 1988; p. 68. ISBN 1-55608-010-7

- or see Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Cohomology", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- E. Cline, B. Parshall, L. Scott and W. van der Kallen, (1977) "Rational and generic cohomology" Inventiones Mathematicae 39 (2), pp. 143–163.

- Asadollahi, Javad and Salarian, Shokrollah (2007) "Cohomology theories for complexes" Journal of Pure & Applied Algebra 210 (3), pp. 771–787.

| ||||||||||||||||