International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts

The International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts (French: L'Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes) was a World's fair held in Paris, France, from April to October 1925. The term "Art Deco" was derived by shortening the words Arts Décoratifs, in the title of this exposition,[1] and it was popularised in the late 1960s by British art critic and historian, Bevis Hillier.[2] Artistic creation in the années folles in France is marked by this event, when on this occasion many ideas of the international avant-garde in the fields of architecture and applied arts were brought together. This major event of the 20s was located between the esplanade of Les Invalides and the entrances of the Grand Palais and Petit Palais. It received 4,000 guests at the inauguration on April 28, and thousands of visitors each of the following days.

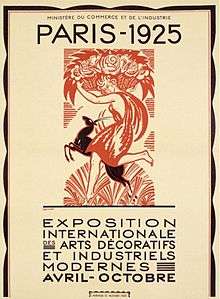

This exhibition epitomized what came to be called decades later "Art Deco," a "modern" style characterized by a streamlined classicism, geometric and symmetric compositions, and a sleek machine-age look. The Exposition poster, by Robert Bonfils, imitating the look of a woodblock print, featured a modern athletic nymph and a racing gazelle. René Lalique's crystal tower fountain was a prominent set-piece of the Exposition. Other prominent motifs included stylized animals, lightning flashes, and "Aztec" (and other exotic) motifs. Some of these were motifs and the design aesthetic was derived from French Decorative Cubism, German Bauhaus, Italian Futurism, and Russian Constructivism.

The central body of exhibits seemed to present the fashionable products of the luxury market, a signal that, after the disasters of World War I, Paris still reigned supreme in the arts of design. At the same time, other examples such as the Esprit Nouveau pavilion and the Soviet pavilion were distinctly not decorative,[3] they contained furnishings and paintings but these works, including the pavilions, were spare and modern. The modern architecture of Le Corbusier and Konstantin Melnikov attracted both criticism and admiration for its lack of ornamentation. Criticism focused on the 'nakedness' of these structures,[4] compared to other pavilions at the exhibition, such as the Pavilion of the Collector by the ébéniste-decorator Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann. These modernist works were integral projects of their own specific movements, so today the term "Art Deco" is used for other works at the exposition with more accuracy.

Le Corbusier's Esprit Nouveau pavilion attracted attention for reasons in addition to its modernism, such as his vast theoretical project that the pavilion embodied. L'Esprit Nouveau was the name of the Rive Gauche journal in which Le Corbusier first published excerpts of his book Vers une architecture,[5] and within this pavilion he exhibited his Plan Voisin for Paris. The Plan Voisin, named for aviation pioneer Gabriel Voisin,[3] was a series of identical 200 meter tall skyscrapers and lower rectangular apartments, that would replace a large section of central Paris in the Rive Droite.[6] Although this was never built, the pavilion was and represented a single modular apartment within the broader urban theoretical project.[7]

Notable examples of Russian constructivism were the Alexander Rodchenko designed worker's club, and Konstantin Melnikov designed Soviet pavilion.[8] Vadim Meller was awarded a gold medal for his scenic design. Student work from Vkhutemas won several prizes,[9] and Melnikov's pavilion won the Grand Prix.[4] Due to continued national tensions after the first world war, Germany was not invited. Austria however contributed Frederick Kiesler's City in Space exhibit to house the Viennese documentation, this exhibit was commissioned by Josef Hoffman.[9]

Polish graphic arts were also successfully represented. Tadeusz Gronowski won the Grand Prix in that category. Danish architect and designer Arne Jacobsen, still a student, won a silver medal for a chair design.[10]

Among the 15,000 exhibitors Croatian sculptor and architect Ivan Meštrović was awarded a Grand Prix for The Racic Mausoleum in Cavtat.

References

- ↑ Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

- ↑ Bevis Hillier, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s (Studio Vista/Dutton Picturebacks), 1968

- 1 2 Dr Harry Francis Mallgrave, Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673-1968, Cambridge University Press, 2005, page 258, ISBN 0-521-79306-8

- 1 2 Catherine Cooke, Russian Avant-Garde: Theories of Art, Architecture, and the City, Academy Editions, 1995, Page 143.

- ↑ Hanno-Walter Kruft, A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present, Princeton Architectural Press, 1994, Page 397, ISBN 1-56898-010-8

- ↑ Anthony Sutcliffe, Paris: An Architectural History, Yale University Press, 1993, Page 143, ISBN 0-300-06886-7

- ↑ Christopher Green, Art in France, 1900-1940, Yale University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-300-09908-8

- ↑ MoMA | exhibitions | Rodchenko | Worker's Club 1925

- 1 2 Penelope Curtis, Sculpture 1900-1945: After Rodin, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ↑ "Arne Jacobsen". Design Museum. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Exposition internationale des Arts Décoratifs et industriels modernes (1925). |

Coordinates: 48°51′49″N 2°18′49″E / 48.8636°N 2.3136°E

| ||||||