Exchange interaction

In physics, the exchange interaction (with an exchange energy, and exchange term) is a quantum mechanical effect that only occurs between identical particles. Despite sometimes being called an exchange force in analogy to classical force, it is not a true force, as it lacks a force carrier.

The effect is due to the wave function of indistinguishable particles being subject to exchange symmetry, that is, either remaining unchanged (symmetric) or changing its sign (antisymmetric) when two particles are exchanged. Both bosons and fermions can experience the exchange interaction. For fermions, it is sometimes called Pauli repulsion and related to the Pauli exclusion principle. For bosons, the exchange interaction takes the form of an effective attraction that causes identical particles to be found closer together, as in Bose–Einstein condensation.

The exchange interaction alters the expectation value of the distance when the wave functions of two or more indistinguishable particles overlap. It increases (for fermions) or decreases (for bosons) the expectation value of the distance between identical particles (as compared to distinguishable particles).[1] Among other consequences, the exchange interaction is responsible for ferromagnetism and for the volume of matter. It has no classical analogue.

Exchange interaction effects were discovered independently by physicists Werner Heisenberg[2] and Paul Dirac[3] in 1926.

"Force" description

The exchange interaction is sometimes called the exchange force. However, it is not a true force and should not be confused with the exchange forces produced by the exchange of force carriers, such as the electromagnetic force produced between two electrons by the exchange of a photon, or the strong force between two quarks produced by the exchange of a gluon.[4]

Although sometimes erroneously described as a force, the exchange interaction is a purely quantum mechanical effect unlike other forces.

Exchange Interactions between localized electron magnetic moments

Quantum mechanical particles are classified as bosons or fermions. The spin–statistics theorem of quantum field theory demands that all particles with half-integer spin behave as fermions and all particles with integer spin behave as bosons. Multiple bosons may occupy the same quantum state; by the Pauli exclusion principle, however, no two fermions can occupy the same state. Since electrons have spin 1/2, they are fermions. This means that the overall wave function of a system must be antisymmetric when two electrons are exchanged, i.e. interchanged with respect to both spatial and spin coordinates. First, however, exchange will be explained with the neglect of spin.

Exchange of spatial coordinates

Taking a hydrogen molecule-like system (i.e. one with two electrons), we may attempt to model the state of each electron by first assuming the electrons behave independently, and taking wave functions in position space of  for the first electron and

for the first electron and  for the second electron. We assume that

for the second electron. We assume that  and

and  are orthogonal, and that each corresponds to an energy eigenstate of its electron. Now, we may construct a wave function for the overall system in position space by using an antisymmetric combination of the product wave functions in position space:

are orthogonal, and that each corresponds to an energy eigenstate of its electron. Now, we may construct a wave function for the overall system in position space by using an antisymmetric combination of the product wave functions in position space:

-

![\Psi_A(\vec r_1,\vec r_2)= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[\Phi_a(\vec r_1) \Phi_b(\vec r_2) - \Phi_b(\vec r_1) \Phi_a(\vec r_2)]](../I/m/193486cd1191988ce480f90a774c7bd0.png)

(1)

Alternatively, we may also construct the overall position–space wave function by using a symmetric combination of the product wave functions in position space:

-

![\Psi_S(\vec r_1,\vec r_2)= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[\Phi_a(\vec r_1) \Phi_b(\vec r_2) + \Phi_b(\vec r_1) \Phi_a(\vec r_2)]](../I/m/464c662b110aae68fa62a31d0be7e716.png)

(2)

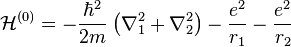

Treating the exchange interaction in the hydrogen molecule by the perturbation method, the overall Hamiltonian is:

=

=  +

+

where  and

and

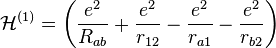

Two eigenvalues for the system energy are found:

-

(3)

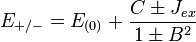

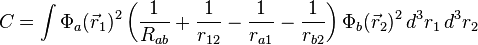

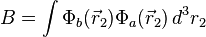

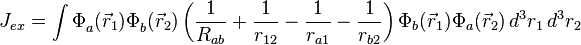

where the E+ is the spatially symmetric solution and E− is the spatially antisymmetric solution. A variational calculation yields similar results.  can be diagonalized by using the position–space functions given by Eqs. (1) and (2). In Eq. (3), C is the Coulomb integral, B is the overlap integral, and Jex is the exchange integral. These integrals are given by:

can be diagonalized by using the position–space functions given by Eqs. (1) and (2). In Eq. (3), C is the Coulomb integral, B is the overlap integral, and Jex is the exchange integral. These integrals are given by:

-

(4)

-

(5)

-

(6)

The terms in parentheses in Eqs. (4) and (6) correspond to: proton–proton repulsion (Rab), electron–electron repulsion (r12), and electron–proton attraction (ra1/a2/b1/b2).All quantities are assumed to be real.

Although in the hydrogen molecule the exchange integral, Eq. (6), is negative, Heisenberg first suggested that it changes sign at some critical ratio of internuclear distance to mean radial extension of the atomic orbital.[5][6][7]

Inclusion of spin

The symmetric and antisymmetric combinations in Eqs. (1) and (2) did not include the spin variables (α = spin-up; β = spin down); there are also antisymmetric and symmetric combinations of the spin variables:

-

±

±

(7)

To obtain the overall wave function, these spin combinations have to be coupled with Eqs. (1) and (2). The resulting overall wave functions, called spin-orbitals, are written as Slater determinants. When the orbital wave function is symmetrical the spin one must be anti-symmetrical and vice versa. Accordingly, E+ above corresponds to the spatially symmetric/spin-singlet solution and E− to the spatially antisymmetric/spin-triplet solution.

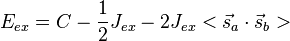

J. H. Van Vleck presented the following analysis:[8]

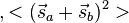

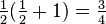

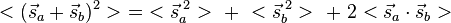

- The potential energy of the interaction between the two electrons in orthogonal orbitals can be represented by a matrix, say Eex. From Eq. (3), the characteristic values of this matrix are C ± Jex. The characteristic values of a matrix are its diagonal elements after it is converted to a diagonal matrix. Now, the characteristic values of the square of the magnitude of the resultant spin

is

is  . The characteristic values of the matrices

. The characteristic values of the matrices  and

and  are each

are each  and

and  . The characteristic values of the scalar product

. The characteristic values of the scalar product  are

are  and

and  , corresponding to both the spin-singlet (S = 0)

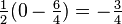

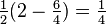

, corresponding to both the spin-singlet (S = 0) - and spin-triplet (S = 1) states, respectively. From Eq. (3) and the aforementioned relations, the matrix Eex is seen to have the characteristic value C + Jex when

has the characteristic value −3/4 (i.e. when S = 0; the spatially symmetric/spin-singlet state). Alternatively, it has the characteristic value C − Jex when

has the characteristic value −3/4 (i.e. when S = 0; the spatially symmetric/spin-singlet state). Alternatively, it has the characteristic value C − Jex when  has the characteristic value +1/4 (i.e. when S = 1; the spatially antisymmetric/spin-triplet state). Therefore,

has the characteristic value +1/4 (i.e. when S = 1; the spatially antisymmetric/spin-triplet state). Therefore,

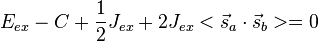

-

(8)

- and, hence,

-

(9)

- where the spin momenta are given as

and

and  .

.

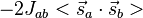

Dirac pointed out that the critical features of the exchange interaction could be obtained in an elementary way by neglecting the first two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. (9), thereby considering the two electrons as simply having their spins coupled by a potential of the form:

-

(10)

It follows that the exchange interaction Hamiltonian between two electrons in orbitals Φa and Φb can be written in terms of their spin momenta  and

and  . This is named the Heisenberg Exchange Hamiltonian or the Heisenberg–Dirac Hamiltonian in the older literature:

. This is named the Heisenberg Exchange Hamiltonian or the Heisenberg–Dirac Hamiltonian in the older literature:

-

(11)

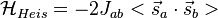

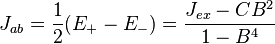

Jab is not the same as the quantity labeled Jex in Eq. (6). Rather, Jab, which is termed the exchange constant, is a function of Eqs. (4), (5), and (6), namely,

-

(12)

However, with orthogonal orbitals (in which B = 0), for example with different orbitals in the same atom, Jab = Jex.

Effects of exchange

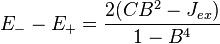

If Jab is positive the exchange energy favors electrons with parallel spins; this is a primary cause of ferromagnetism in materials in which the electrons are considered localized in the Heitler–London model of chemical bonding, but this model of ferromagnetism has severe limitations in solids (see below). If Jab is negative, the interaction favors electrons with antiparallel spins, potentially causing antiferromagnetism. The sign of Jab is essentially determined by the relative sizes of Jex and the product of CB2. This can be deduced from the expression for the difference between the energies of the triplet and singlet states, E− − E+:

-

(13)

Although these consequences of the exchange interaction are magnetic in nature, the cause is not; it is due primarily to electric repulsion and the Pauli exclusion principle. Indeed, in general, the direct magnetic interaction between a pair of electrons (due to their electron magnetic moments) is negligibly small compared to this electric interaction.

Exchange energy splittings are very elusive to calculate for molecular systems at large internuclear distances. However, analytical formulae have been worked out for the hydrogen molecular ion (see references herein).

Normally, exchange interactions are very short-ranged, confined to electrons in orbitals on the same atom (intra-atomic exchange) or nearest neighbor atoms (direct exchange) but longer-ranged interactions can occur via intermediary atoms and this is termed Superexchange.

Direct exchange interactions in solids

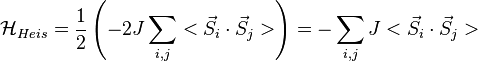

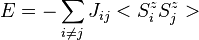

In a crystal, generalization of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian in which the sum is taken over the exchange Hamiltonians for all the (i,j) pairs of atoms of the many-electron system gives:.

-

(14)

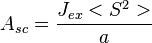

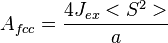

The 1/2 factor is introduced because the interaction between the same two atoms is counted twice in performing the sums. Note that the J in Eq.(14) is the exchange constant Jab above not the exchange integral Jex. The exchange integral Jex is related to yet another quantity, called the exchange stiffness constant (A) which serves as a characteristic of a ferromagnetic material. The relationship is dependent on the crystal structure. For a simple cubic lattice with lattice parameter  ,

,

-

(15)

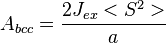

For a body-centered cubic lattice,

-

(16)

and for a face-centered cubic lattice,

-

(17)

The form of Eq. (14) corresponds identically to the Ising [statistical mechanical] model of ferromagnetism except that in the Ising model, the dot product of the two spin angular momenta is replaced by the scalar product SijSji. The Ising model was invented by Wilhelm Lenz in 1920 and solved for the one-dimensional case by his doctoral student Ernst Ising in 1925. The energy of the Ising model is defined to be:

-

(18)

Limitations of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian and the localized electron model in solids

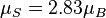

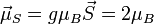

Because the Heisenberg Hamiltonian presumes the electrons involved in the exchange coupling are localized in the context of the Heitler–London, or valence bond (VB), theory of chemical bonding, it is an adequate model for explaining the magnetic properties of electrically insulating narrow-band ionic and covalent non-molecular solids where this picture of the bonding is reasonable. Nevertheless, theoretical evaluations of the exchange integral for non-molecular solids that display metallic conductivity in which the electrons responsible for the ferromagnetism are itinerant (e.g. iron, nickel, and cobalt) have historically been either of the wrong sign or much too small in magnitude to account for the experimentally determined exchange constant (e.g. as estimated from the Curie temperatures via TC ≈ 2⟨J⟩/3kB where ⟨J⟩ is the exchange interaction averaged over all sites). The Heisenberg model thus cannot explain the observed ferromagnetism in these materials.[9] In these cases, a delocalized, or Hund–Mulliken–Bloch (molecular orbital/band) description, for the electron wave functions is more realistic. Accordingly, the Stoner model of ferromagnetism is more applicable. In the Stoner model, the spin-only magnetic moment (in Bohr magnetons) per atom in a ferromagnet is given by the difference between the number of electrons per atom in the majority spin and minority spin states. The Stoner model thus permits non-integral values for the spin-only magnetic moment per atom. However, with ferromagnets ![\mu_S = - g \mu_B [S(S+1)]^{1/2}](../I/m/743e3fe64b02df506c5a164c39bbff43.png) (g = 2.0023 ≈ 2) tends to overestimate the total spin-only magnetic moment per atom. For example, a net magnetic moment of 0.54 μB per atom for Nickel metal is predicted by the Stoner model, which is very close to the 0.61 Bohr magnetons calculated based on the metal's observed saturation magnetic induction, its density, and its atomic weight.[10] By contrast, an isolated Ni atom (electron configuration = 3d84s2) in a cubic crystal field will have two unpaired electrons of the same spin (hence,

(g = 2.0023 ≈ 2) tends to overestimate the total spin-only magnetic moment per atom. For example, a net magnetic moment of 0.54 μB per atom for Nickel metal is predicted by the Stoner model, which is very close to the 0.61 Bohr magnetons calculated based on the metal's observed saturation magnetic induction, its density, and its atomic weight.[10] By contrast, an isolated Ni atom (electron configuration = 3d84s2) in a cubic crystal field will have two unpaired electrons of the same spin (hence,  ) and would thus be expected to have in the localized electron model a total spin magnetic moment of

) and would thus be expected to have in the localized electron model a total spin magnetic moment of  (but the measured spin-only magnetic moment along one axis, the physical observable, will be given by

(but the measured spin-only magnetic moment along one axis, the physical observable, will be given by  ). Generally, valence s and p electrons are best considered delocalized, while 4f electrons are localized and 5f and 3d/4d electrons are intermediate, depending on the particular internuclear distances.[11] In the case of substances where both delocalized and localized electrons contribute to the magnetic properties (e.g. rare-earth systems), the Ruderman–Kittel–Kasuya–Yosida (RKKY) model is the currently accepted mechanism.

). Generally, valence s and p electrons are best considered delocalized, while 4f electrons are localized and 5f and 3d/4d electrons are intermediate, depending on the particular internuclear distances.[11] In the case of substances where both delocalized and localized electrons contribute to the magnetic properties (e.g. rare-earth systems), the Ruderman–Kittel–Kasuya–Yosida (RKKY) model is the currently accepted mechanism.

See also

- Double-exchange mechanism

- Exchange symmetry

- Pauli exclusion principle

- Slater determinant

- Superexchange

- Holstein–Herring method

- Spin-exchange interaction

- Multipolar exchange interaction

References

- ↑ David J. Griffiths: Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, Second Edition, pp. 207–210

- ↑ Mehrkörperproblem und Resonanz in der Quantenmechanik, W. Heisenberg, Zeitschrift für Physik 38, #6–7 (June 1926), pp. 411–426. DOI 10.1007/BF01397160.

- ↑ On the Theory of Quantum Mechanics, P. A. M. Dirac, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A 112, #762 (October 1, 1926), pp. 661—677.

- ↑ Exchange Forces, HyperPhysics, Georgia State University, accessed June 2, 2007.

- ↑ Derivation of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian, Rebecca Hihinashvili, accessed on line October 2, 2007.

- ↑ Quantum Theory of Magnetism: Magnetic Properties of Materials, Robert M. White, 3rd rev. ed., Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2007, section 2.2.7. ISBN 3-540-65116-0.

- ↑ The Theory of Electric and Magnetic Susceptibilities, J. H. van Vleck, London: Oxford University Press, 1932, chapter XII, section 76.

- ↑ Van Vleck, J. H.: Electric and Magnetic Susceptibilities, Oxford, Clarendon Press, p. 318 (1932).

- ↑ see, for example, Stuart, R. and Marshall, W. Phys. Rev. 120, 353 (1960).

- ↑ Elliot, S. R.: The Physics and Chemistry of Solids, John Wiley & Sons, New York, p. 615 (1998)

- ↑ J. B. Goodenough: Magnetism and the Chemical Bond, Interscience Publishers, New York, pp. 5–17 (1966).

Further reading

- Cytter, Y.; Neuhauser, D.; Baer, R. (2014). "Metropolis Evaluation of the Hartree–Fock Exchange Energy". J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10: 4317–4323. doi:10.1021/ct500450w.

External links

- Exchange Mechanisms in E. Pavarini, E. Koch, F. Anders, and M. Jarrell: Correlated Electrons: From Models to Materials, Jülich 2012, ISBN 978-3-89336-796-2

- Exchange Interaction and Energy

- Exchange Interaction and Exchange Anisotropy