Examples of Markov chains

This page contains examples of Markov chains in action.

Board games played with dice

A game of snakes and ladders or any other game whose moves are determined entirely by dice is a Markov chain, indeed, an absorbing Markov chain. This is in contrast to card games such as blackjack, where the cards represent a 'memory' of the past moves. To see the difference, consider the probability for a certain event in the game. In the above-mentioned dice games, the only thing that matters is the current state of the board. The next state of the board depends on the current state, and the next roll of the dice. It doesn't depend on how things got to their current state. In a game such as blackjack, a player can gain an advantage by remembering which cards have already been shown (and hence which cards are no longer in the deck), so the next state (or hand) of the game is not independent of the past states.

A center-biased random walk

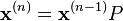

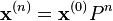

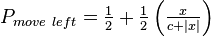

Consider a random walk on the number line where, at each step, the position (call it x) may change by +1 (to the right) or −1 (to the left) with probabilities:

(where c is a constant greater than 0)

For example if the constant, c, equals 1, the probabilities of a move to the left at positions x = −2,−1,0,1,2 are given by  respectively. The random walk has a centering effect that weakens as c increases.

respectively. The random walk has a centering effect that weakens as c increases.

Since the probabilities depend only on the current position (value of x) and not on any prior positions, this biased random walk satisfies the definition of a Markov chain.

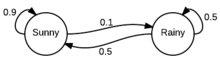

A very simple weather model

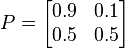

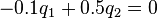

The probabilities of weather conditions (modeled as either rainy or sunny), given the weather on the preceding day, can be represented by a transition matrix:

The matrix P represents the weather model in which a sunny day is 90% likely to be followed by another sunny day, and a rainy day is 50% likely to be followed by another rainy day. The columns can be labelled "sunny" and "rainy", and the rows can be labelled in the same order.

(P)i j is the probability that, if a given day is of type i, it will be followed by a day of type j.

Notice that the rows of P sum to 1: this is because P is a stochastic matrix.

Predicting the weather

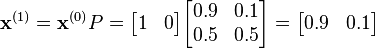

The weather on day 0 is known to be sunny. This is represented by a vector in which the "sunny" entry is 100%, and the "rainy" entry is 0%:

The weather on day 1 can be predicted by:

Thus, there is a 90% chance that day 1 will also be sunny.

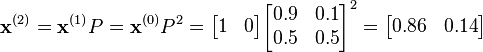

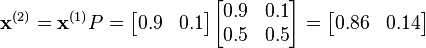

The weather on day 2 can be predicted in the same way:

or

General rules for day n are:

Steady state of the weather

In this example, predictions for the weather on more distant days are increasingly inaccurate and tend towards a steady state vector. This vector represents the probabilities of sunny and rainy weather on all days, and is independent of the initial weather.

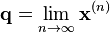

The steady state vector is defined as:

but converges to a strictly positive vector only if P is a regular transition matrix (that is, there is at least one Pn with all non-zero entries).

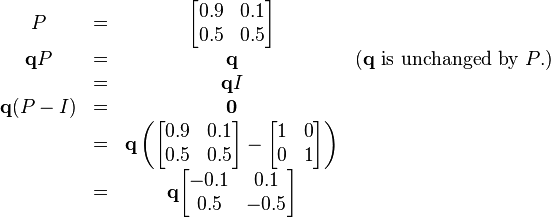

Since the q is independent from initial conditions, it must be unchanged when transformed by P. This makes it an eigenvector (with eigenvalue 1), and means it can be derived from P. For the weather example:

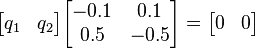

So

and since they are a probability vector we know that

and since they are a probability vector we know that

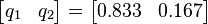

Solving this pair of simultaneous equations gives the steady state distribution:

In conclusion, in the long term, about 83.3% of days are sunny.

Citation ranking

Google's page rank algorithm is essentially a Markov chain over the graph of the Web. More information can be found in "The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web" by Larry Page, Sergey Brin, R. Motwani, and T. Winograd .