Everyman (play)

| Everyman | |

|---|---|

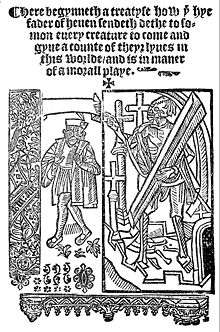

Frontispiece from edition of Everyman published by John Skot c. 1530. | |

| Written by |

unknown; anonymous translation of Elckerlijc, by Petrus Dorlandus |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | c. 1510 |

| Original language | Middle English |

| Subject | Reckoning, Salvation |

| Genre | Morality play |

The Somonyng of Everyman (The Summoning of Everyman), usually referred to simply as Everyman, is a late 15th-century morality play. Like John Bunyan's 1678 Christian novel The Pilgrim's Progress, Everyman uses allegorical characters to examine the question of Christian salvation and what Man must do to attain it. The premise is that the good and evil deeds of one's life will be tallied by God after death, as in a ledger book. The play is the allegorical accounting of the life of Everyman, who represents all mankind. In the course of the action, Everyman tries to convince other characters to accompany him in the hope of improving his account. All the characters are also allegorical, each personifying an abstract idea such as Fellowship, (material) Goods, and Knowledge. The conflict between good and evil is dramatised by the interactions between characters. Everyman is being singled out because it is difficult for him to find characters to accompany him on his pilgrimage. Everyman eventually realizes through this pilgrimage that he is essentially alone, despite all the personified characters that were supposed necessities and friends to him. Everyman learns that when you are brought to death and placed before God all you are left with is your own good deeds.

Sources

The play was written in Middle English during the Tudor period, but the identity of the author is unknown. Although the play was apparently produced with some frequency in the seventy-five years following its composition, no production records survive.[1]

There is a similar Dutch-language (Flemish) morality play of the same period called Elckerlijc. Scholars have yet to reach complete agreement on which of these plays was the original, or even on their relation to a later Latin work named Homulus.[2][3] However, Arthur Cawley goes so far as to say that the "evidence for … Elckerlijk is certainly very strong".[4]

Setting

The cultural setting is based on the Roman Catholicism of the era. Everyman attains afterlife in heaven by means of good works and the Catholic Sacraments, in particular Confession, Penance, Unction, Viaticum and receiving the Eucharist.

Synopsis

The oldest surviving example of the script begins with this paragraph on the frontispiece:

Here begynneth a treatyse how þe hye Fader of Heven sendeth Dethe to somon every creature to come and gyve acounte of theyr lyves in this worlde, and is in maner of a morall playe.Here begins a treatise how the high Father of Heaven sends Death to summon every creature to come and give account of their lives in this world, and is in the manner of a moral play.

The play opens with a prologue, which takes the form of a messenger telling the audience to attend to the action to come, and to heed its lesson.

Then God speaks, lamenting that humans have become too absorbed in material wealth and riches to follow Him. He feels taken for granted, because He receives no appreciation from mankind for all that he has given them.

"Of ghostly sight the people be so blind,

Drowned in sin, they know me not for their God;

They fear not my rightwiseness, the sharp rod..."

In worldly riches is all their mind,

So God commands Death, His messenger, to go to Everyman and summon him to heaven to make his reckoning. Death arrives at Everyman's side and informs him it is time for him to die and face judgment.

"On thee thou must take a long journey:

Therefore thy book of count with thee thou bring;

And look thou be sure of thy reckoning..."

For turn again thou can not by no way,

Upon hearing this, Everyman is distressed as he does not have a proper account of his life prepared. So Everyman tries to bribe Death, and begs for more time. Death denies Everyman's requests, but will allow him to find a companion for his journey, someone to speak for his good virtues.

"Yea, if any be so hardy

That would go with thee and bear thee company.

Thy reckoning to give before his presence."

Hie thee that you were gone to God’s magnificence,

Fellowship, representing Everyman's friends, enters and promises to go anywhere with him. However, when Fellowship hears of the true nature of Everyman's journey, he refuses to go, saying that he would stay with Everyman to enjoy life but will not accompany him on a journey to death.

"If Death were the messenger,

For no man that is living to-day

I would not forsake you, while the day is clear...

I will not go that loath journey...

yet if thou wilt eat, and drink, and make good cheer,

Or haunt to women, the lusty companion,

Everyman then calls on Kindred and Cousin, who represent family, and asks them to go with him. Kindred refuses outright:

"Ah, sir; what, ye be a merry man!

Take good heart to you, and make no moan.

As for me, ye shall go alone."

But as one thing I warn you, by Saint Anne,

Cousin also refuses by making excuses:

"No by our Lady; I have the cramp in my toe.

Trust not to me, for, so God me speed,

I will deceive you in your most need.

In refusing to accompany Everyman, Cousin explains a fundamental reason why no people will accompany Everyman: they have their own accounts to write as well.

"For verily I will not go with you;

Also of mine an unready reckoning

Now, God keep thee, for now I go."

I have to account; therefore I make tarrying.

Everyman realises that he has put much love in material Goods, so Goods will surely come with him on his journey with Death. But Goods will not come, saying that since Everyman was so devoted to gathering Goods during his life, but never shared them with the less fortunate, Goods' presence would only make God's judgment of Everyman more severe.

"Nay, Everyman, I sing another song,

I follow no man in such voyages;

Thou shouldst fare much the worse for me..."

For and I went with thee

Everyman then turns to Good Deeds. Good Deeds says she would go with him, but she is too weak as Everyman has not loved her in his life.

"If ye had perfectly cheered me,

Your book of account now full ready had be.

To your soul’s heaviness."

Look, the books of your works and deeds eke;

Oh, see how they lie under the feet,

Good Deeds summons her sister Knowledge to accompany them, and together they go to see Confession.

"Now we go together lovingly,

To Confession, that cleansing river."

Confession offers Everyman a "jewel" called Penance if he repents his sins to God and suffers pain to make amends:

"I will you comfort as well as I can,

And a precious jewel I will give thee,

Therewith shall your body chastised be..."

Called penance, wise voider of adversity;

In the presence of Confession, Everyman begs God for forgiveness and repents his sins, punishing himself with a scourge:

"My body sore punished shall be:

Take this body for the sin of the flesh;

Therefore suffer now strokes and punishing!"

Also though delightest to go gay and fresh;

And in the way of damnation thou did me brine;

After his scourging, Confession declares that Everyman is absolved of his sins, and as a result, Good Deeds becomes strong enough to accompany Everyman on his journey with Death.

"Everyman, pilgrim, my special friend,

Blessed by thou without end;

Therefore I will bid by thee in every stound."

For thee is prepared the eternal glory,

Ye gave me made whole and sound,

Knowledge gifts Everyman with "a garment of sorrow" made from his own tears, then Good Deeds summons Beauty, Strength, Discretion and Five Wits (i.e. the five senses) to join them. They all agree to accompany Everyman as he goes to a priest to take sacrament.

"Everyman, hearken what I say;

Go to priesthood, I you advise,

The holy sacrament and ointment together..."

And receive of him in any wise

But after taking the sacrament, Everyman tells them where his journey ends, and again they all abandon him – except for Good Deeds.

"O all thing faileth, save God alone;

Beauty, Strength, and Discretion;

They all run from me full fast."

For when Death bloweth his blast,

Beauty, Strength, Discretion, and the Five Wits are all qualities that fade as a person gets older. Knowledge cannot accompany him after he leaves his physical body, but will stay with him until the time of death.

"Nay, yet I will not depart from hence depart,

Till I see where ye shall be come."

Content at last, Everyman climbs into his grave with Good Deeds at his side and dies, after which they ascend together into heaven, where they are welcomed by an Angel.

"Now the soul is taken the body fro;

Thy reckoning is crystal-clear.

That liveth well before the day of doom."

Now shalt thou into the heavenly sphere,

Unto the which all ye shall come

The play closes as the Doctor, representing a scholar, enters and provides an epilogue, explaining to the audience the moral of the story: that in the end, a man will only have his Good Deeds to accompany him beyond the grave.

"And he that hath his account whole and sound,

High in heaven he shall be crowned;

Amen, say ye, for saint Charity."

Unto which place God bring us all thither

That we may live body and soul together.

Thereto help the Trinity,

Adaptations

A modern stage production of Everyman did not appear until July 1901 when The Elizabethan Stage Society of William Poel gave three outdoor performances at the Charterhouse in London.[5] Poel then partnered with British actor Ben Greet to produce the play throughout Britain, with runs on the American Broadway stage from 1902 to 1918,[6] and concurrent tours throughout North America. These productions differed from past performances in that women were cast in the title role, rather than men. Film adaptations of the 1901 version of the play appeared in 1913 and 1914, with the 1913 film being presented with an early color two-process pioneered by Kinemacolor.[7][8]

Another well-known version of the play is Jedermann by the Austrian playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal, which has been performed annually at the Salzburg Festival since 1920.[9] The play was made into a film in 1961. Frederick Franck published a modernised version of the tale entitled "Everyone", drawing on Buddhist influence.[10] A direct-to-video film of Everyman was made in 2002, directed by John Farrell, which updated the setting to the early 21st century, including Death as a businessman in dark glasses with a briefcase, and Goods being played by a talking personal computer.[11]

A modernized adaptation by Carol Ann Duffy, the Poet Laureate, with Chiwetel Ejiofor in the title role, was performed at the National Theatre (UK) from April to July 2015.[12]

Notes

- ↑ Literature of the Western World, Volume I, The Ancient World Through the Renaissance, Fifth Edition

- ↑ Tigg 1939.

- ↑ de Vocht 1947.

- ↑ Cawley 1984, p. 434.

- ↑ Kuehler, Stephen G., (2008), Concealing God: The "Everyman" revival, 1901–1903, Tufts University (PhD. thesis), 104 p.

- ↑ Everyman (Broadway play) at the Internet Broadway Database

- ↑ Everyman at the Internet Movie Database – 1913 film version.

- ↑ Everyman at the Internet Movie Database – 1914 film version.

- ↑ Banham 1998, p. 491.

- ↑ "Everyman’s God". sitm.info.

- ↑ "Everyman (2002)". IMDb. 17 July 2002.

- ↑ "BBC Radio 4 - Saturday Review, Everyman, Far from the Madding Crowd, Empire, Anne Enright, Christopher Williams". BBC.

References

- Banham, Martin, ed. (1998), The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, ISBN 0-521-43437-8

- Cawley, A. C. (1961), Everyman and Medieval Miracle Plays, Everyman's Library, ISBN 0-460-87280-X

- Cawley, A. C. (1984), "Rev. of The Dutch Elckerlijc Is Prior to the English Everyman, by E. R. Tigg", Review of English Studies 35 (139): 434

- Cawley, A. C. (1989), "Everyman", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ISBN 0-684-17024-8

- Meijer, Reinder (1971), Literature of the Low Countries: A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium, New York: Twayne Publishers, pp. 55–57, 62, ISBN 978-9024721009

- Tigg, E. R. (1939), "Is "Elckerlyc" prior to "Everyman"?", Journal of English and Germanic Philology 38: 568–596, JSTOR 27704551

- Takahashi, Genji (1953), A Study of Everyman with Special Reference to the Source of its Plot, Ai-iku-sha, pp. 33–39, ASIN B0007JDF9M

- de Vocht, Henry (1947), Everyman: A Comparative Study of Texts and Sources, Material for the Study of the Old English Drama 20, Louvain: Librairie Universitaire

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Everyman (play) |

| ||||||||||||||||

|