Eurynome (Oceanid)

| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Aquatic deities |

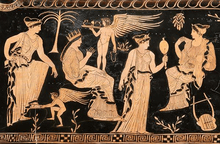

Eurynome (/jʊˈrɪnəmiː/; Greek: Εὐρυνόμη) was a deity of ancient Greek religion worshipped at a sanctuary near the confluence of rivers called the Neda and the Lymax in classical Peloponnesus. She was represented by a statue of what we would call a mermaid. Tradition, as reported by the Greek traveller, Pausanias, identified her with the Oceanid, or “daughter of Ocean”, of Greek poetry.

Main myths

In the epic tradition, Eurynome was one of the elder Oceanides, that is, a daughter of Oceanus and Tethys.[1] Eurynome was the third bride of Zeus and mother of the Charites, goddesses of grace and beauty.[2]

When Hephaestus was cast from Olympus by the goddess Hera, who was disgusted at having borne a crippled child, he was caught by Eurynome and Thetis (possibly a doubling for Tethys, her mother). Eurynome and Thetis nursed the god Hephaestus on the banks of the earth-encircling river Oceanus, after his fall from heaven.[3] Charis, Eurynome's daughter, later became Hephaestus' bride.[4]

Eurynome is closely identified with another Eurynome, Queen of the Titans. This Eurynome was an early Titan queen who ruled Olympus beside her husband Ophion. The pair were wrestled for their thrones by Cronus and Rhea who cast them down into the earth-encircling river Oceanus.[5] She may have been the same as the Titan Tethys whose river-god sons nurtured the pastures and whose daughter Eurynome was goddess of pasturelands. Eurynome's husband Ophion "the Serpent" was similar to Tethys' husband Oceanus, who in classical art was represented with a serpentine-fish tail in place of legs and holding a snake (ophis). It is also possible that Ophion and Eurynome (daughter of Oceanus) were equated with Uranus (Heaven) and Gaia (Earth). In the Orphic Theogonies Gaia was the daughter of Hydrus (Water), a primordial being similar to Oceanus. It was Uranus who Cronus wrestles for the throne of Olympus in Hesiod's Theogony.[6]

Worship

Eurynome was worshipped at the confluence of the rivers Neda and Lymax in Arcadia. Her xoanon, which could only be viewed when her sanctuary was opened once a year, was a wooden statue bound in golden chains depicting a woman's upper body and the lower body of a fish.[7] Her son Asopus was the god of a nearby stream in the adjacent region of Sikyonia. The fish-tailed goddess, Eurynome, worshipped in Arcadia, may have been Eurynome wife of Ophion, Tethys the wife of Oceanus, Eurynome mother of the Charites, the goddess of the river Neda, or a watery Artemis.[8]

Etymology of the name

The name is usually segmented Eury-nome, where eury- is “wide”. This segment appears in Linear B as e-u-ru–, a prefix in a few men’s names. It does not occur in any Mycenaean women’s names, nor does –nome.

The root of –nome is Proto-Indo-European *nem-, distribute, as in the Greek infinitive, nemein, “to distribute.” Words derived from *nem- had a large variety of senses. In the case of Eurynome, the two main senses proposed are “wanderer” and “ruler”.

Robert Graves saw in Eurynome a lunar goddess descending from the Pre-Hellenic mother goddess of Neolithic Europe. In that case, –nome is as in our word nomad. The nomad wanders searching for pastureland, or land that has been “distributed” for the use of domestic animals. The moon is to be regarded as wandering. In the other interpretation, –nome is as in English auto-nomy. A ruler is someone who “distributes” law and justice. Neither case has any bearing on the status of Eurynome as a possible Pelasgian mother goddess.

If Eurynome was the descendant of a pre-Greek goddess, she must have had a pre-Greek name, and not the Greek name, Eurynome. If the name is Indo-European, it might have evolved into Greek with the rest of the language. If it is not Indo-European, then it might result from renaming or from selecting the closest Greek homonym.

Sources

Some major sources are paraphrased or quoted below.

Homer

Iliad 18.388ff

- The earliest known reference to the Oceanid is a passage in the Iliad relating what happened to Hephaistos after his mother, Hera, threw him from Olympos. Thetis and Eurynome, the daughter of Oceanus, offered him refuge. He stayed with them for nine years in their cave at the edge of the ocean making splendiferous artifacts.

Hesiod

Homer and Hesiod establish that a belief in the Oceanid existed in the earliest literary times. The most likely circumstance, based on the testimony of Pausanias, is that both authors took their themes from a religion known to and believed in by all the Hellenes; thus, it is probably best to assume that Eurynome the Oceanid is the same Oceanid of ancient Greek belief mentioned in all the classical sources.

Pausanias

8.41.5, 6

- [5] “Eurynome is believed by the people of Phigalia to be a surname of Artemis. Those of them, however, to whom have descended ancient traditions, declare that Eurynome was a daughter of Ocean, whom Homer mentions in the Iliad, saying that along with Thetis she received Hephaestus. On the same day in each year they open the sanctuary of Eurynome, but at any other time it is a transgression for them to open it.

- [6] On this occasion sacrifices also are offered by the state and by individuals. I did not arrive at the season of the festival, and I did not see the image of Eurynome; but the Phigalians told me that golden chains bind the wooden image, which represents a woman as far as the hips, but below this a fish. If she is a daughter of Ocean, and lives with Thetis in the depth of the sea, the fish may be regarded as a kind of emblem of her. But there could be no probable connection between such a shape and Artemis.”

9.35.5

Apollodorus

- 1.2.2. The Oceanids, including Eurynome, were the daughters of Ocean and Tethys.

- 1.3.1. The Graces are the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome.

- 3.12.6. Some say the river Asopus is the son of Zeus and Eurynome.

Creation myth

A few important sources relate a creation myth. The main source is Apollonius of Rhodes, who is quoted in the article on Ophion. The details are not repeated here.

Robert Graves, one of the chief scholars interested in the myth, saw in this passage a possible Pelasgian creation myth. Putting together what was then beginning to be known of Neolithic Greece and its connections to the orient, he hypothesized that Eurynome originally was another manifestation of the Neolithic mother goddess.

The Ophion article takes a skeptical approach on the grounds that he read too much into the sources. As he did not rely only on the sources, this article presents some of Graves’ wider arguments:

- The egg and the snake. The rebirth of the world from an egg and the use of the snake as a symbol of regenerative power is a strong theme of what Marija Gimbutas called “the language of the goddess”; that is, the common (but undeciphered) writing system attested on Neolithic pottery of much of Europe, including the Balkans. In another myth, the Pelasgians descend from the teeth of Ophion, which ostensibly means “snake.”

- As the Neolithics either entered the Balkans from the eastern Mediterranean region or kept close ties with the Natufians there, Graves makes comparisons with and draws parallels to mythic elements among cultures to which the Natufians descended; that is, the entire Middle East. For example, he compares her to Sumerian Iahu, “exalted dove”, which he believed became the name of Jehovah.

- Many if not most of the names of Greek mythology are believed to have come from pre-Greek elements. For example, the Proto-Indo-Europeans had no word for ocean or travel upon it. Okeanos is a pre-Greek word, as are Olympos, Tethys and Titan.

- The antiquity of Eurynome and Ophion are sufficiently attested in the sources to warrant a presumption that they descend from prehistoric times. Only the prefix, Eury-, appears in the most ancient known Greek, but that is sufficient to demonstrate the remoteness of the names in time from later poetic mythologizers such as Apollonius.

Graves’ views attract more attention as time goes by, perhaps because of increasing knowledge about the Neolithic. At the present time, however, they are still regarded as mainly speculation. Concerning prehistoric Europe, archaeology and speculation are all we have at the moment. Even if some of Graves’ detail can be shown to be wrong, no proof exists that his overall views, based on the synthesis of many elements, are either true or untrue.

References

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 346 ff (trans. Evelyn-White)

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 907 ff (trans. Evelyn-White)

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 13. 397 ff (trans. Lattimore)

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece 9. 35. 1

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1. 503 ff (trans. Aldrich)

- ↑ Theoi Project, Aaron J. Atsma

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece 8. 41. 4 - 6 (trans. Jones)

- ↑ Theoi Project, Aaron J. Atsma

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|