Euler's laws of motion

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

|

Core topics |

In classical mechanics, Euler's laws of motion are equations of motion which extend Newton's laws of motion for point particle to rigid body motion.[1] They were formulated by Leonhard Euler about 50 years after Isaac Newton formulated his laws.

Overview

Euler's first law

Euler's first law states that the linear momentum of a body, p (also denoted G) is equal to the product of the mass of the body m and the velocity of its center of mass vcm: [1][2][3]

.

.

Internal forces between the particles that make up a body do not contribute to changing the total momentum of the body as there is an equal and opposite force resulting in no net effect.[4] The law is also stated as:[4]

.

.

where acm = dvcm/dt is the acceleration of the centre of mass and F = dp/dt is the total applied force on the body. This is just the time derivative of the previous equation (m is a constant).

Euler's second law

Euler's second law states that the rate of change of angular momentum L (sometimes denoted H) about a point that is fixed in an inertial reference frame (often the mass center of the body), is equal to the sum of the external moments of force (torques) acting on that body M (also denoted τ or Γ) about that point:[1][2][3]

.

.

Note that the above formula holds only if both M and L are computed with respect to a fixed inertial frame or a frame parallel to the inertial frame but fixed on the center of mass. For rigid bodies translating and rotating in only 2D, this can be expressed as:[5]

,

,

where rcm is the position vector of the center of mass with respect to the point about which moments are summed, α is the angular acceleration of the body about its center of mass, and I is the moment of inertia of the body about its center of mass. See also Euler's equations (rigid body dynamics).

Explanation and derivation

The distribution of internal forces in a deformable body are not necessarily equal throughout, i.e. the stresses vary from one point to the next. This variation of internal forces throughout the body is governed by Newton's second law of motion of conservation of linear momentum and angular momentum, which for their simplest use are applied to a mass particle but are extended in continuum mechanics to a body of continuously distributed mass. For continuous bodies these laws are called Euler’s laws of motion. If a body is represented as an assemblage of discrete particles, each governed by Newton’s laws of motion, then Euler’s equations can be derived from Newton’s laws. Euler’s equations can, however, be taken as axioms describing the laws of motion for extended bodies, independently of any particle distribution.[6]

The total body force applied to a continuous body with mass m, mass density ρ, and volume V, is the volume integral integrated over the volume of the body:

where b is the force acting on the body per unit mass (dimensions of acceleration, misleadingly called the "body force"), and dm = ρ dV is an infinitesimal mass element of the body.

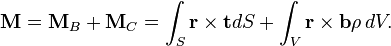

Body forces and contact forces acting on the body lead to corresponding moments (torques) of those forces relative to a given point. Thus, the total applied torque M about the origin is given by

where MB and MC respectively indicate the moments caused by the body and contact forces.

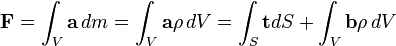

Thus, the sum of all applied forces and torques (with respect to the origin of the coordinate system) acting on the body can be given as the sum of a volume and surface integral:

where t = t(n) is called the surface traction, integrated over the surface of the body, in turn n denotes a unit vector normal and directed outwards to the surface S.

Let the coordinate system (x1, x2, x3) be an inertial frame of reference, r be the position vector of a point particle in the continuous body with respect to the origin of the coordinate system, and v = dr/dt be the velocity vector of that point.

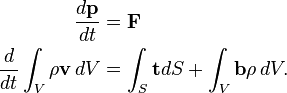

Euler’s first axiom or law (law of balance of linear momentum or balance of forces) states that in an inertial frame the time rate of change of linear momentum p of an arbitrary portion of a continuous body is equal to the total applied force F acting on that portion, and it is expressed as

Euler’s second axiom or law (law of balance of angular momentum or balance of torques) states that in an inertial frame the time rate of change of angular momentum L of an arbitrary portion of a continuous body is equal to the total applied torque M acting on that portion, and it is expressed as

Where  is the velocity,

is the velocity,  the volume, and the derivatives of p and L are material derivatives.

the volume, and the derivatives of p and L are material derivatives.

See also

- List of topics named after Leonhard Euler

- Euler's laws of rigid body rotations

- Newton-Euler equations of motion with 6 components, combining Euler's two laws into one equation.

References

- 1 2 3 McGill and King (1995). Engineering Mechanics, An Introduction to Dynamics (3rd ed.). PWS Publishing Company. ISBN 0-534-93399-8.

- 1 2 "Euler's Laws of Motion". Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- 1 2 Rao, Anil Vithala (2006). Dynamics of particles and rigid bodies. Cambridge University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-521-85811-3.

- 1 2 Gray, Gary L.; Costanzo, Plesha (2010). Engineering Mechanics: Dynamics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-282871-9.

- ↑ Ruina, Andy; Rudra Pratap (2002). Introduction to Statics and Dynamics (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 771. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ↑ Lubliner, Jacob (2008). Plasticity Theory (Revised Edition) (PDF). Dover Publications. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-486-46290-0.