Eugene Burton Ely

| Eugene Burton Ely | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

October 21, 1886 Williamsburg, Iowa |

| Died |

October 19, 1911 (aged 24) Macon, Georgia |

| Place of burial | Williamsburg, Iowa |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Navy |

| Awards | Distinguished Flying Cross (posthumously) |

| Spouse(s) | Mabel Hall |

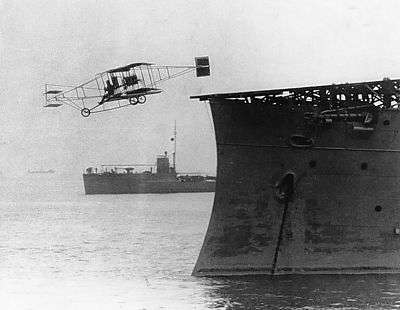

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886[1] – October 19, 1911) was an aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft take off and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa and raised in Davenport, Iowa. Having completed the eighth grade, he graduated from Davenport Grammar School 4 in January 1901.[2] Although some sources indicate that he attended and graduated from Iowa State University in 1904 (when he would have been 17), the registrar of ISU reports that there is no record of him having done so (nor did he attend the University of Iowa or the University of Northern Iowa).[3] Ely likewise does not appear in the graduations lists for Davenport High School.[4] By 1904 he was employed as a chauffeur to the Rev. Fr. Smyth, a Catholic priest in Cosgrove, Iowa, who shared Ely's love of fast driving; in Father Smyth's car (a red Franklin), Ely set the speed record between Iowa City and Davenport.[5]

Ely was living in San Francisco at the time of the earthquake and fire[6] and was active there in the early days of the sales and racing of automobiles.[7] He married Mabel Hall on August 7, 1907; he was 21 and she was 17, which meant the marriage required her mother's consent;[7][8] they honeymooned in Colorado.[9] The Elys relocated to Nevada City, California in 1909, and for a time he drove an "auto stage" delivery route.[10]

The couple moved to Portland, Oregon in early 1910, where he got a job as an auto salesman, working for E. Henry Wemme.[7] Soon after, Wemme purchased one of Glenn Curtiss' first four-cylinder biplanes and acquired the franchise for the Pacific Northwest. Wemme was unable to fly the Curtiss biplane, but Ely, believing that flying was as easy as driving a car, offered to fly it. He ended up crashing it instead, and feeling responsible, bought the wreck from Wemme.[7] Within a few months he had repaired the aircraft and learned to fly.[7] He flew it in the Portland area, then headed to Minneapolis, Minnesota in June 1910 to participate in an exhibition, where he met Curtiss and started working for him.[7] After an unsuccessful attempt in Sioux City, Iowa,[11] Ely's first reported exhibition on behalf of Curtiss was in Winnipeg in July 1910.[12] Ely received Aero Club of America pilot's license #17 on 5 October 1910.[7]

Naval aviation firsts

In October, Ely and Curtiss met Captain Washington Chambers, USN, who had been appointed by George von Lengerke Meyer, the Secretary of the Navy, to investigate military uses for aviation within the Navy. This led to two experiments. On November 14, 1910, Ely took off in a Curtiss pusher from a temporary platform erected over the bow of the light cruiser USS Birmingham.[7][nb 1] The airplane plunged downward as soon as it cleared the 83-foot platform runway; and the aircraft wheels dipped into the water before rising.[7] Ely's goggles were covered with spray, and the aviator promptly landed on a beach rather than circling the harbor and landing at the Norfolk Navy Yard as planned.[7] John Barry Ryan offered $500 to build the platform, and a $500 prize, for a ship to shore flight.[14]

Two months later, on January 18, 1911, Ely landed his Curtiss pusher airplane on a platform on the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania anchored in San Francisco Bay.[nb 2] Ely flew from the Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California and landed on the Pennsylvania, which was the first successful shipboard landing of an aircraft.[16][17] This flight was also the first ever using a tailhook system, designed and built by circus performer and aviator Hugh Robinson.[7] Ely told a reporter: "It was easy enough. I think the trick could be successfully turned nine times out of ten."

Ely communicated with the United States Navy requesting employment, but United States naval aviation was not yet organized.[7] Ely continued flying in exhibitions while Captain Chambers promised to "keep him in mind" if Navy flying stations were created.[7] Captain Chambers advised Ely to cut out the sensational features for his safety and the sake of aviation.[7] When asked about retiring, The Des Moines Register quoted Ely as replying: "I guess I will be like the rest of them, keep at it until I am killed."[7]

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the flight, Naval Commander Bob Coolbaugh flew a personally built replica of Ely's Curtiss from the runway at NAS Norfolk on November 12, 2010. The U.S. Navy planned to feature the flying demonstration at Naval anniversary events across America.[18]

Death

On October 19, 1911, while flying at an exhibition in Macon, Georgia, his plane was late pulling out of a dive and crashed.[7] Ely jumped clear of the wrecked aircraft, but his neck was broken, and he died a few minutes later.[7] Spectators picked the wreckage clean looking for souvenirs, including Ely's gloves, tie and cap.[19] On what would have been his twenty-fifth birthday, his body was returned to his birthplace for burial.[20]

On February 16, 1933, Congress awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously to Ely, "for extraordinary achievement as a pioneer civilian aviator and for his significant contribution to the development of aviation in the United States Navy."[21] An exhibit of retired naval aircraft at Naval Air Station Norfolk in Virginia bears Ely's name, and a granite historical marker in Newport News, Virginia, overlooks the waters where Ely made his historic flight in 1911 and recalls his contribution to military aviation, naval in particular.

See also

- List of fatalities from aviation accidents

- List of firsts in aviation

- Charles Rumney Samson, the first pilot to take off from a moving ship

- Edwin Harris Dunning, the first pilot to land on a moving ship

Notes

- ↑ Modifications for take-off required outfitting the ship with “an 83-foot-long ramp, sloping 5 degrees over the bow. The ramp’s forward edge was 37 feet above the water”.[13]

- ↑ “The landing platform, constructed of pine planks, was 130 feet long by 32 feet wide. Ten feet of it hung at an angle -- with a drop of four feet -- over the stern of the ship. The arresting gear comprised 21 ropes -- each with 50-pound sandbags attached to either end -- laid across the runway. Each rope was suspended 8 inches above the deck. Three hooks had been affixed to the underside of the aircraft to catch on the ropes when the landing was made”.[15]

References

- ↑ 1900 census, Scott County, Iowa. Williamsburg (IA) Historical Commission Obituary Collection Index

- ↑ Davenport Daily Leader, January 21, 1901, p. 4.

- ↑ Becky Jordan, reference specialist, Iowa State University, March 12, 2012

- ↑ Richardson-Sloane Special Collections Center, Davenport Public Library, March 26, 2012

- ↑ Iowa City Daily Press, August 26, 1904, p. 4; September 28, 1904, p. 4; December 3, 1904, p. 8; December 5, 1904, p. 1

- ↑ Williamsburg Journal Tribune, April 26, 1906, p. 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Moore(January 1981)pp.58–63

- ↑ Genforum Genealogy courtesy of Cathy Gowder

- ↑ Williamsburg Journal Tribune, August 29, 1907, p. 10

- ↑ http://www.nevadacityadvocate.com/nevada-city/3723.html

- ↑ Atlantic Daily Telegraph, July 2, 1910, p. 6

- ↑ "WinnipegREALTORS®". winnipegrealtors.ca. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ Mersky, P. (2011). "Ely’s Flights – Part 1, The First Launch". Approach: The Naval Safety Center's Aviation Magazine 56 (1): 3.

- ↑ Hiller B. Zobel, John H. Zobel, "Those Magnificent Men", American Heritage, Winter 2011, pp.46–51

- ↑ Demers, D.J. (2011). "What goes up…". Naval History 25 (1): 48.

- ↑ Accessed February 8, 2007.

- ↑ Accessed February 8, 2007.

- ↑ "EAAer Flies Curtiss Pusher Replica in Navy Centennial Ceremony". Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ Skylark: the life, lies, and inventions of Harry Atwood. p. 25.

- ↑ Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, October 21, 1911, p. 16.

- ↑ U.S. Air Services, Vol. XVIII No. 3 p. 14 (March 1933)

- Moore, John Hammond (January 1981). "The Short, Eventful Life of Eugene B. Ely". United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- Article in Hampton-Roads Pilot

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eugene Ely. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|