Euclidean vector

In mathematics, physics, and engineering, a Euclidean vector (sometimes called a geometric[1] or spatial vector,[2] or—as here—simply a vector) is a geometric object that has magnitude (or length) and direction and can be added to other vectors according to vector algebra. A Euclidean vector is frequently represented by a line segment with a definite direction, or graphically as an arrow, connecting an initial point A with a terminal point B,[3] and denoted by

A vector is what is needed to "carry" the point A to the point B; the Latin word vector means "carrier".[4] It was first used by 18th century astronomers investigating planet rotation around the Sun.[5] The magnitude of the vector is the distance between the two points and the direction refers to the direction of displacement from A to B. Many algebraic operations on real numbers such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and negation have close analogues for vectors, operations which obey the familiar algebraic laws of commutativity, associativity, and distributivity. These operations and associated laws qualify Euclidean vectors as an example of the more generalized concept of vectors defined simply as elements of a vector space.

Vectors play an important role in physics: velocity and acceleration of a moving object and forces acting on it are all described by vectors. Many other physical quantities can be usefully thought of as vectors. Although most of them do not represent distances (except, for example, position or displacement), their magnitude and direction can be still represented by the length and direction of an arrow. The mathematical representation of a physical vector depends on the coordinate system used to describe it. Other vector-like objects that describe physical quantities and transform in a similar way under changes of the coordinate system include pseudovectors and tensors.

History

The concept of vector, as we know it today, evolved gradually over a period of more than 200 years. About a dozen people made significant contributions.[6]

Giusto Bellavitis abstracted the basic idea in 1835 when he established the concept of equipollence. Working in a Euclidean plane, he made equipollent any pair of line segments of the same length and orientation. Essentially he realized an equivalence relation on the pairs of points in the plane and thus erected the first space of vectors in the plane.[6]:52–4

The term vector was introduced by William Rowan Hamilton as part of his system of quaternions q = s + v where "scalar" s ∈ ℝ and "vector" v ∈ ℝ3. Thus Hamilton's vectors are 3-dimensional. Like Bellavitis, Hamilton viewed vectors as representative of classes of equipollent directed segments. As complex numbers use an imaginary unit to complement the real line, Hamilton considered vectors v to be the "imaginary part" of quaternions:

- The algebraically imaginary part, being geometrically constructed by a straight line, or radius vector, which has, in general, for each determined quaternion, a determined length and determined direction in space, may be called the vector part, or simply the vector of the quaternion.[7]

Several other mathematicians developed vector-like systems in the middle of the nineteenth century, including Augustin Cauchy, Hermann Grassmann, August Möbius, Comte de Saint-Venant, and Matthew O'Brien. Grassmann's 1840 work Theorie der Ebbe und Flut (Theory of the Ebb and Flow) was the first system of spatial analysis similar to today's system and had ideas corresponding to the cross product, scalar product and vector differentiation. Grassmann's work was largely neglected until the 1870s.[6]

Peter Guthrie Tait carried the quaternion standard after Hamilton. His 1867 Elementary Treatise of Quaternions included extensive treatment of the nabla or del operator ∇.

In 1878 Elements of Dynamic was published by William Kingdon Clifford. Clifford simplified the quaternion study by isolating the dot product and cross product of two vectors from the complete quaternion product. This approach made vector calculations available to engineers and others working in three dimensions and skeptical of the fourth.

Josiah Willard Gibbs, who was exposed to quaternions through James Clerk Maxwell's Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, separated off their vector part for independent treatment. The first half of Gibbs's Elements of Vector Analysis, published in 1881, presents what is essentially the modern system of vector analysis.[6] In 1901 Edwin Bidwell Wilson published Vector Analysis, adapted from Gibb's lectures, which banished any mention of quaternions in the development of vector calculus.

Overview

In physics and engineering, a vector is typically regarded as a geometric entity characterized by a magnitude and a direction. It is formally defined as a directed line segment, or arrow, in a Euclidean space.[8] In pure mathematics, a vector is defined more generally as any element of a vector space. In this context, vectors are abstract entities which may or may not be characterized by a magnitude and a direction. This generalized definition implies that the above-mentioned geometric entities are a special kind of vectors, as they are elements of a special kind of vector space called Euclidean space.

This article is about vectors strictly defined as arrows in Euclidean space. When it becomes necessary to distinguish these special vectors from vectors as defined in pure mathematics, they are sometimes referred to as geometric, spatial, or Euclidean vectors.

Being an arrow, a Euclidean vector possesses a definite initial point and terminal point. A vector with fixed initial and terminal point is called a bound vector. When only the magnitude and direction of the vector matter, then the particular initial point is of no importance, and the vector is called a free vector. Thus two arrows  and

and  in space represent the same free vector if they have the same magnitude and direction: that is, they are equivalent if the quadrilateral ABB′A′ is a parallelogram. If the Euclidean space is equipped with a choice of origin, then a free vector is equivalent to the bound vector of the same magnitude and direction whose initial point is the origin.

in space represent the same free vector if they have the same magnitude and direction: that is, they are equivalent if the quadrilateral ABB′A′ is a parallelogram. If the Euclidean space is equipped with a choice of origin, then a free vector is equivalent to the bound vector of the same magnitude and direction whose initial point is the origin.

The term vector also has generalizations to higher dimensions and to more formal approaches with much wider applications.

Examples in one dimension

Since the physicist's concept of force has a direction and a magnitude, it may be seen as a vector. As an example, consider a rightward force F of 15 newtons. If the positive axis is also directed rightward, then F is represented by the vector 15 N, and if positive points leftward, then the vector for F is −15 N. In either case, the magnitude of the vector is 15 N. Likewise, the vector representation of a displacement Δs of 4 meters to the right would be 4 m or −4 m, and its magnitude would be 4 m regardless.

In physics and engineering

Vectors are fundamental in the physical sciences. They can be used to represent any quantity that has magnitude, has direction, and which adheres to the rules of vector addition. An example is velocity, the magnitude of which is speed. For example, the velocity 5 meters per second upward could be represented by the vector (0,5) (in 2 dimensions with the positive y axis as 'up'). Another quantity represented by a vector is force, since it has a magnitude and direction and follows the rules of vector addition. Vectors also describe many other physical quantities, such as linear displacement, displacement, linear acceleration, angular acceleration, linear momentum, and angular momentum. Other physical vectors, such as the electric and magnetic field, are represented as a system of vectors at each point of a physical space; that is, a vector field. Examples of quantities that have magnitude and direction but fail to follow the rules of vector addition: Angular displacement and electric current. Consequently, these are not vectors.

In Cartesian space

In the Cartesian coordinate system, a vector can be represented by identifying the coordinates of its initial and terminal point. For instance, the points A = (1,0,0) and B = (0,1,0) in space determine the free vector  pointing from the point x=1 on the x-axis to the point y=1 on the y-axis.

pointing from the point x=1 on the x-axis to the point y=1 on the y-axis.

Typically in Cartesian coordinates, one considers primarily bound vectors. A bound vector is determined by the coordinates of the terminal point, its initial point always having the coordinates of the origin O = (0,0,0). Thus the bound vector represented by (1,0,0) is a vector of unit length pointing from the origin along the positive x-axis.

The coordinate representation of vectors allows the algebraic features of vectors to be expressed in a convenient numerical fashion. For example, the sum of the vectors (1,2,3) and (−2,0,4) is the vector

- (1, 2, 3) + (−2, 0, 4) = (1 − 2, 2 + 0, 3 + 4) = (−1, 2, 7).

Euclidean and affine vectors

In the geometrical and physical settings, sometimes it is possible to associate, in a natural way, a length or magnitude and a direction to vectors. In turn, the notion of direction is strictly associated with the notion of an angle between two vectors. When the length of vectors is defined, it is possible to also define a dot product — a scalar-valued product of two vectors — which gives a convenient algebraic characterization of both length (the square root of the dot product of a vector by itself) and angle (a function of the dot product between any two non-zero vectors). In three dimensions, it is further possible to define a cross product which supplies an algebraic characterization of the area and orientation in space of the parallelogram defined by two vectors (used as sides of the parallelogram).

However, it is not always possible or desirable to define the length of a vector in a natural way. This more general type of spatial vector is the subject of vector spaces (for bound vectors) and affine spaces (for free vectors). An important example is Minkowski space that is important to our understanding of special relativity, where there is a generalization of length that permits non-zero vectors to have zero length. Other physical examples come from thermodynamics, where many of the quantities of interest can be considered vectors in a space with no notion of length or angle.[9]

Generalizations

In physics, as well as mathematics, a vector is often identified with a tuple of components, or list of numbers, that act as scalar coefficients for a set of basis vectors. When the basis is transformed, for example by rotation or stretching, then the components of any vector in terms of that basis also transform in an opposite sense. The vector itself has not changed, but the basis has, so the components of the vector must change to compensate. The vector is called covariant or contravariant depending on how the transformation of the vector's components is related to the transformation of the basis. In general, contravariant vectors are "regular vectors" with units of distance (such as a displacement) or distance times some other unit (such as velocity or acceleration); covariant vectors, on the other hand, have units of one-over-distance such as gradient. If you change units (a special case of a change of basis) from meters to millimeters, a scale factor of 1/1000, a displacement of 1 m becomes 1000 mm–a contravariant change in numerical value. In contrast, a gradient of 1 K/m becomes 0.001 K/mm–a covariant change in value. See covariance and contravariance of vectors. Tensors are another type of quantity that behave in this way; a vector is one type of tensor.

In pure mathematics, a vector is any element of a vector space over some field and is often represented as a coordinate vector. The vectors described in this article are a very special case of this general definition because they are contravariant with respect to the ambient space. Contravariance captures the physical intuition behind the idea that a vector has "magnitude and direction".

Representations

Vectors are usually denoted in lowercase boldface, as a or lowercase italic boldface, as a. (Uppercase letters are typically used to represent matrices.) Other conventions include  or a, especially in handwriting. Alternatively, some use a tilde (~) or a wavy underline drawn beneath the symbol, e.g.

or a, especially in handwriting. Alternatively, some use a tilde (~) or a wavy underline drawn beneath the symbol, e.g.  , which is a convention for indicating boldface type. If the vector represents a directed distance or displacement from a point A to a point B (see figure), it can also be denoted as

, which is a convention for indicating boldface type. If the vector represents a directed distance or displacement from a point A to a point B (see figure), it can also be denoted as  or AB. Especially in literature in German it was common to represent vectors with small fraktur letters as

or AB. Especially in literature in German it was common to represent vectors with small fraktur letters as  .

.

Vectors are usually shown in graphs or other diagrams as arrows (directed line segments), as illustrated in the figure. Here the point A is called the origin, tail, base, or initial point; point B is called the head, tip, endpoint, terminal point or final point. The length of the arrow is proportional to the vector's magnitude, while the direction in which the arrow points indicates the vector's direction.

On a two-dimensional diagram, sometimes a vector perpendicular to the plane of the diagram is desired. These vectors are commonly shown as small circles. A circle with a dot at its centre (Unicode U+2299 ⊙) indicates a vector pointing out of the front of the diagram, toward the viewer. A circle with a cross inscribed in it (Unicode U+2297 ⊗) indicates a vector pointing into and behind the diagram. These can be thought of as viewing the tip of an arrow head on and viewing the flights of an arrow from the back.

In order to calculate with vectors, the graphical representation may be too cumbersome. Vectors in an n-dimensional Euclidean space can be represented as coordinate vectors in a Cartesian coordinate system. The endpoint of a vector can be identified with an ordered list of n real numbers (n-tuple). These numbers are the coordinates of the endpoint of the vector, with respect to a given Cartesian coordinate system, and are typically called the scalar components (or scalar projections) of the vector on the axes of the coordinate system.

As an example in two dimensions (see figure), the vector from the origin O = (0,0) to the point A = (2,3) is simply written as

The notion that the tail of the vector coincides with the origin is implicit and easily understood. Thus, the more explicit notation  is usually not deemed necessary and very rarely used.

is usually not deemed necessary and very rarely used.

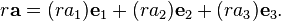

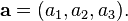

In three dimensional Euclidean space (or R3), vectors are identified with triples of scalar components:

- also written

This can be generalised to n-dimensional Euclidean space (or Rn).

These numbers are often arranged into a column vector or row vector, particularly when dealing with matrices, as follows:

Another way to represent a vector in n-dimensions is to introduce the standard basis vectors. For instance, in three dimensions, there are three of them:

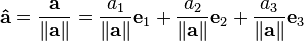

These have the intuitive interpretation as vectors of unit length pointing up the x, y, and z axis of a Cartesian coordinate system, respectively. In terms of these, any vector a in R3 can be expressed in the form:

or

where a1, a2, a3 are called the vector components (or vector projections) of a on the basis vectors or, equivalently, on the corresponding Cartesian axes x, y, and z (see figure), while a1, a2, a3 are the respective scalar components (or scalar projections).

In introductory physics textbooks, the standard basis vectors are often instead denoted  (or

(or  , in which the hat symbol ^ typically denotes unit vectors). In this case, the scalar and vector components are denoted respectively ax, ay, az, and ax, ay, az (note the difference in boldface). Thus,

, in which the hat symbol ^ typically denotes unit vectors). In this case, the scalar and vector components are denoted respectively ax, ay, az, and ax, ay, az (note the difference in boldface). Thus,

The notation ei is compatible with the index notation and the summation convention commonly used in higher level mathematics, physics, and engineering.

Decomposition

As explained above a vector is often described by a set of vector components that add up to form the given vector. Typically, these components are the projections of the vector on a set of mutually perpendicular reference axes (basis vectors). The vector is said to be decomposed or resolved with respect to that set.

However, the decomposition of a vector into components is not unique, because it depends on the choice of the axes on which the vector is projected.

Moreover, the use of Cartesian unit vectors such as  as a basis in which to represent a vector is not mandated. Vectors can also be expressed in terms of an arbitrary basis, including the unit vectors of a cylindrical coordinate system (

as a basis in which to represent a vector is not mandated. Vectors can also be expressed in terms of an arbitrary basis, including the unit vectors of a cylindrical coordinate system ( ) or spherical coordinate system (

) or spherical coordinate system ( ). The latter two choices are more convenient for solving problems which possess cylindrical or spherical symmetry respectively.

). The latter two choices are more convenient for solving problems which possess cylindrical or spherical symmetry respectively.

The choice of a basis doesn't affect the properties of a vector or its behaviour under transformations.

A vector can be also decomposed with respect to "non-fixed" basis vectors that change their orientation as a function of time or space. For example, a vector in three-dimensional space can be decomposed with respect to two axes, respectively normal, and tangent to a surface (see figure). Moreover, the radial and tangential components of a vector relate to the radius of rotation of an object. The former is parallel to the radius and the latter is orthogonal to it.[10]

In these cases, each of the components may be in turn decomposed with respect to a fixed coordinate system or basis set (e.g., a global coordinate system, or inertial reference frame).

Basic properties

The following section uses the Cartesian coordinate system with basis vectors

and assumes that all vectors have the origin as a common base point. A vector a will be written as

Equality

Two vectors are said to be equal if they have the same magnitude and direction. Equivalently they will be equal if their coordinates are equal. So two vectors

and

are equal if

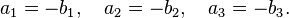

Opposite, parallel, and antiparallel vectors

Two vectors are opposite if they have the same magnitude but opposite direction. So two vectors

and

are opposite if

Two vectors are parallel if they have the same direction but not necessarily the same magnitude, or antiparallel if they have opposite direction but not necessarily the same magnitude.

Addition and subtraction

Assume now that a and b are not necessarily equal vectors, but that they may have different magnitudes and directions. The sum of a and b is

The addition may be represented graphically by placing the tail of the arrow b at the head of the arrow a, and then drawing an arrow from the tail of a to the head of b. The new arrow drawn represents the vector a + b, as illustrated below:

This addition method is sometimes called the parallelogram rule because a and b form the sides of a parallelogram and a + b is one of the diagonals. If a and b are bound vectors that have the same base point, this point will also be the base point of a + b. One can check geometrically that a + b = b + a and (a + b) + c = a + (b + c).

The difference of a and b is

Subtraction of two vectors can be geometrically defined as follows: to subtract b from a, place the tails of a and b at the same point, and then draw an arrow from the head of b to the head of a. This new arrow represents the vector a − b, as illustrated below:

Subtraction of two vectors may also be performed by adding the opposite of the second vector to the first vector, that is, a − b = a + (−b).

Scalar multiplication

A vector may also be multiplied, or re-scaled, by a real number r. In the context of conventional vector algebra, these real numbers are often called scalars (from scale) to distinguish them from vectors. The operation of multiplying a vector by a scalar is called scalar multiplication. The resulting vector is

Intuitively, multiplying by a scalar r stretches a vector out by a factor of r. Geometrically, this can be visualized (at least in the case when r is an integer) as placing r copies of the vector in a line where the endpoint of one vector is the initial point of the next vector.

If r is negative, then the vector changes direction: it flips around by an angle of 180°. Two examples (r = −1 and r = 2) are given below:

Scalar multiplication is distributive over vector addition in the following sense: r(a + b) = ra + rb for all vectors a and b and all scalars r. One can also show that a − b = a + (−1)b.

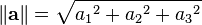

Length

The length or magnitude or norm of the vector a is denoted by ‖a‖ or, less commonly, |a|, which is not to be confused with the absolute value (a scalar "norm").

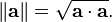

The length of the vector a can be computed with the Euclidean norm

which is a consequence of the Pythagorean theorem since the basis vectors e1, e2, e3 are orthogonal unit vectors.

This happens to be equal to the square root of the dot product, discussed below, of the vector with itself:

- Unit vector

A unit vector is any vector with a length of one; normally unit vectors are used simply to indicate direction. A vector of arbitrary length can be divided by its length to create a unit vector. This is known as normalizing a vector. A unit vector is often indicated with a hat as in â.

To normalize a vector a = [a1, a2, a3], scale the vector by the reciprocal of its length ‖a‖. That is:

- Zero vector

The zero vector is the vector with length zero. Written out in coordinates, the vector is (0, 0, 0), and it is commonly denoted  , 0, or simply 0. Unlike any other vector, it has an arbitrary or indeterminate direction, and cannot be normalized (that is, there is no unit vector that is a multiple of the zero vector). The sum of the zero vector with any vector a is a (that is, 0 + a = a).

, 0, or simply 0. Unlike any other vector, it has an arbitrary or indeterminate direction, and cannot be normalized (that is, there is no unit vector that is a multiple of the zero vector). The sum of the zero vector with any vector a is a (that is, 0 + a = a).

Dot product

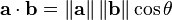

The dot product of two vectors a and b (sometimes called the inner product, or, since its result is a scalar, the scalar product) is denoted by a ∙ b and is defined as:

where θ is the measure of the angle between a and b (see trigonometric function for an explanation of cosine). Geometrically, this means that a and b are drawn with a common start point and then the length of a is multiplied with the length of that component of b that points in the same direction as a.

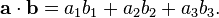

The dot product can also be defined as the sum of the products of the components of each vector as

Cross product

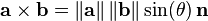

The cross product (also called the vector product or outer product) is only meaningful in three or seven dimensions. The cross product differs from the dot product primarily in that the result of the cross product of two vectors is a vector. The cross product, denoted a × b, is a vector perpendicular to both a and b and is defined as

where θ is the measure of the angle between a and b, and n is a unit vector perpendicular to both a and b which completes a right-handed system. The right-handedness constraint is necessary because there exist two unit vectors that are perpendicular to both a and b, namely, n and (–n).

The cross product a × b is defined so that a, b, and a × b also becomes a right-handed system (but note that a and b are not necessarily orthogonal). This is the right-hand rule.

The length of a × b can be interpreted as the area of the parallelogram having a and b as sides.

The cross product can be written as

For arbitrary choices of spatial orientation (that is, allowing for left-handed as well as right-handed coordinate systems) the cross product of two vectors is a pseudovector instead of a vector (see below).

Scalar triple product

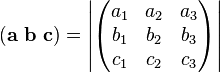

The scalar triple product (also called the box product or mixed triple product) is not really a new operator, but a way of applying the other two multiplication operators to three vectors. The scalar triple product is sometimes denoted by (a b c) and defined as:

It has three primary uses. First, the absolute value of the box product is the volume of the parallelepiped which has edges that are defined by the three vectors. Second, the scalar triple product is zero if and only if the three vectors are linearly dependent, which can be easily proved by considering that in order for the three vectors to not make a volume, they must all lie in the same plane. Third, the box product is positive if and only if the three vectors a, b and c are right-handed.

In components (with respect to a right-handed orthonormal basis), if the three vectors are thought of as rows (or columns, but in the same order), the scalar triple product is simply the determinant of the 3-by-3 matrix having the three vectors as rows

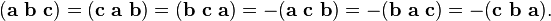

The scalar triple product is linear in all three entries and anti-symmetric in the following sense:

Multiple Cartesian bases

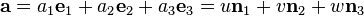

All examples thus far have dealt with vectors expressed in terms of the same basis, namely, e1, e2, e3. However, a vector can be expressed in terms of any number of different bases that are not necessarily aligned with each other, and still remain the same vector. For example, using the vector a from above,

where n1, n2, n3 form another orthonormal basis not aligned with e1, e2, e3. The values of u, v, and w are such that the resulting vector sum is exactly a.

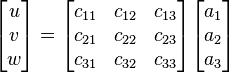

It is not uncommon to encounter vectors known in terms of different bases (for example, one basis fixed to the Earth and a second basis fixed to a moving vehicle). In order to perform many of the operations defined above, it is necessary to know the vectors in terms of the same basis. One simple way to express a vector known in one basis in terms of another uses column matrices that represent the vector in each basis along with a third matrix containing the information that relates the two bases. For example, in order to find the values of u, v, and w that define a in the n1, n2, n3 basis, a matrix multiplication may be employed in the form

where each matrix element cjk is the direction cosine relating nj to ek.[11] The term direction cosine refers to the cosine of the angle between two unit vectors, which is also equal to their dot product.[11]

By referring collectively to e1, e2, e3 as the e basis and to n1, n2, n3 as the n basis, the matrix containing all the cjk is known as the "transformation matrix from e to n", or the "rotation matrix from e to n" (because it can be imagined as the "rotation" of a vector from one basis to another), or the "direction cosine matrix from e to n"[11] (because it contains direction cosines).

The properties of a rotation matrix are such that its inverse is equal to its transpose. This means that the "rotation matrix from e to n" is the transpose of "rotation matrix from n to e".

By applying several matrix multiplications in succession, any vector can be expressed in any basis so long as the set of direction cosines is known relating the successive bases.[11]

Other dimensions

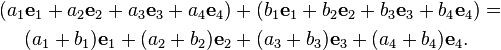

With the exception of the cross and triple products, the above formulae generalise to two dimensions and higher dimensions. For example, addition generalises to two dimensions as

and in four dimensions as

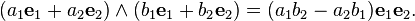

The cross product does not readily generalise to other dimensions, though the closely related exterior product does, whose result is a bivector. In two dimensions this is simply a pseudoscalar

A seven-dimensional cross product is similar to the cross product in that its result is a vector orthogonal to the two arguments; there is however no natural way of selecting one of the possible such products.

Physics

Vectors have many uses in physics and other sciences.

Length and units

In abstract vector spaces, the length of the arrow depends on a dimensionless scale. If it represents, for example, a force, the "scale" is of physical dimension length/force. Thus there is typically consistency in scale among quantities of the same dimension, but otherwise scale ratios may vary; for example, if "1 newton" and "5 m" are both represented with an arrow of 2 cm, the scales are 1:250 and 1 m:50 N respectively. Equal length of vectors of different dimension has no particular significance unless there is some proportionality constant inherent in the system that the diagram represents. Also length of a unit vector (of dimension length, not length/force, etc.) has no coordinate-system-invariant significance.

Vector-valued functions

Often in areas of physics and mathematics, a vector evolves in time, meaning that it depends on a time parameter t. For instance, if r represents the position vector of a particle, then r(t) gives a parametric representation of the trajectory of the particle. Vector-valued functions can be differentiated and integrated by differentiating or integrating the components of the vector, and many of the familiar rules from calculus continue to hold for the derivative and integral of vector-valued functions.

Position, velocity and acceleration

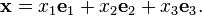

The position of a point x = (x1, x2, x3) in three-dimensional space can be represented as a position vector whose base point is the origin

The position vector has dimensions of length.

Given two points x = (x1, x2, x3), y = (y1, y2, y3) their displacement is a vector

which specifies the position of y relative to x. The length of this vector gives the straight-line distance from x to y. Displacement has the dimensions of length.

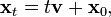

The velocity v of a point or particle is a vector, its length gives the speed. For constant velocity the position at time t will be

where x0 is the position at time t=0. Velocity is the time derivative of position. Its dimensions are length/time.

Acceleration a of a point is vector which is the time derivative of velocity. Its dimensions are length/time2.

Force, energy, work

Force is a vector with dimensions of mass×length/time2 and Newton's second law is the scalar multiplication

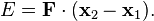

Work is the dot product of force and displacement

Vectors as directional derivatives

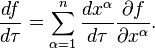

A vector may also be defined as a directional derivative: consider a function  and a curve

and a curve  . Then the directional derivative of

. Then the directional derivative of  is a scalar defined as

is a scalar defined as

where the index  is summed over the appropriate number of dimensions (for example, from 1 to 3 in 3-dimensional Euclidean space, from 0 to 3 in 4-dimensional spacetime, etc.). Then consider a vector tangent to

is summed over the appropriate number of dimensions (for example, from 1 to 3 in 3-dimensional Euclidean space, from 0 to 3 in 4-dimensional spacetime, etc.). Then consider a vector tangent to  :

:

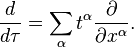

The directional derivative can be rewritten in differential form (without a given function  ) as

) as

Therefore, any directional derivative can be identified with a corresponding vector, and any vector can be identified with a corresponding directional derivative. A vector can therefore be defined precisely as

Vectors, pseudovectors, and transformations

An alternative characterization of Euclidean vectors, especially in physics, describes them as lists of quantities which behave in a certain way under a coordinate transformation. A contravariant vector is required to have components that "transform opposite to the basis" under changes of basis. The vector itself does not change when the basis is transformed; instead, the components of the vector make a change that cancels the change in the basis. In other words, if the reference axes (and the basis derived from it) were rotated in one direction, the component representation of the vector would rotate in the opposite way to generate the same final vector. Similarly, if the reference axes were stretched in one direction, the components of the vector would reduce in an exactly compensating way. Mathematically, if the basis undergoes a transformation described by an invertible matrix M, so that a coordinate vector x is transformed to x′ = Mx, then a contravariant vector v must be similarly transformed via v′ = Mv. This important requirement is what distinguishes a contravariant vector from any other triple of physically meaningful quantities. For example, if v consists of the x, y, and z-components of velocity, then v is a contravariant vector: if the coordinates of space are stretched, rotated, or twisted, then the components of the velocity transform in the same way. On the other hand, for instance, a triple consisting of the length, width, and height of a rectangular box could make up the three components of an abstract vector, but this vector would not be contravariant, since rotating the box does not change the box's length, width, and height. Examples of contravariant vectors include displacement, velocity, electric field, momentum, force, and acceleration.

In the language of differential geometry, the requirement that the components of a vector transform according to the same matrix of the coordinate transition is equivalent to defining a contravariant vector to be a tensor of contravariant rank one. Alternatively, a contravariant vector is defined to be a tangent vector, and the rules for transforming a contravariant vector follow from the chain rule.

Some vectors transform like contravariant vectors, except that when they are reflected through a mirror, they flip and gain a minus sign. A transformation that switches right-handedness to left-handedness and vice versa like a mirror does is said to change the orientation of space. A vector which gains a minus sign when the orientation of space changes is called a pseudovector or an axial vector. Ordinary vectors are sometimes called true vectors or polar vectors to distinguish them from pseudovectors. Pseudovectors occur most frequently as the cross product of two ordinary vectors.

One example of a pseudovector is angular velocity. Driving in a car, and looking forward, each of the wheels has an angular velocity vector pointing to the left. If the world is reflected in a mirror which switches the left and right side of the car, the reflection of this angular velocity vector points to the right, but the actual angular velocity vector of the wheel still points to the left, corresponding to the minus sign. Other examples of pseudovectors include magnetic field, torque, or more generally any cross product of two (true) vectors.

This distinction between vectors and pseudovectors is often ignored, but it becomes important in studying symmetry properties. See parity (physics).

See also

- Affine space, which distinguishes between vectors and points

- Array data structure or Vector (Computer Science)

- Banach space

- Clifford algebra

- Complex number

- Coordinate system

- Covariance and contravariance of vectors

- Four-vector, a non-Euclidean vector in Minkowski space (i.e. four-dimensional spacetime), important in relativity

- Function space

- Grassmann's Ausdehnungslehre

- Hilbert space

- Normal vector

- Null vector

- Pseudovector

- Quaternion

- Tangential and normal components (of a vector)

- Tensor

- Unit vector

- Vector bundle

- Vector calculus

- Vector notation

- Vector-valued function

Notes

- ↑ Ivanov 2001

- ↑ Heinbockel 2001

- ↑ Ito 1993, p. 1678; Pedoe 1988

- ↑ Latin: vectus, perfect participle of vehere, "to carry"/ veho = "I carry". For historical development of the word vector, see "vector n.". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) and Jeff Miller. "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics". Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ↑ The Oxford english dictionary. (2nd. ed.). London: Claredon Press. 2001. ISBN 9780195219425.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael J. Crowe, A History of Vector Analysis; see also his lecture notes at the Wayback Machine (archived January 26, 2004) on the subject.

- ↑ W. R. Hamilton (1846) London, Edinburgh & Dublin Philosophical Magazine 3rd series 29 27

- ↑ Ito 1993, p. 1678

- ↑ Thermodynamics and Differential Forms

- ↑ U. Guelph Physics Dept., "Torque and Angular Acceleration"

- 1 2 3 4 Kane & Levinson 1996, pp. 20–22

References

Mathematical treatments

- Apostol, T. (1967). Calculus, Vol. 1: One-Variable Calculus with an Introduction to Linear Algebra. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-00005-1.

- Apostol, T. (1969). Calculus, Vol. 2: Multi-Variable Calculus and Linear Algebra with Applications. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-00007-5.

- Kane, Thomas R.; Levinson, David A. (1996), Dynamics Online, Sunnyvale, California: OnLine Dynamics, Inc.

- Heinbockel, J. H. (2001), Introduction to Tensor Calculus and Continuum Mechanics, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-55369-133-4

- Ito, Kiyosi (1993), Encyclopedic Dictionary of Mathematics (2nd ed.), MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-59020-4

- Ivanov, A.B. (2001), "Vector, geometric", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Pedoe, D. (1988). Geometry: A comprehensive course. Dover. ISBN 0-486-65812-0..

Physical treatments

- Aris, R. (1990). Vectors, Tensors and the Basic Equations of Fluid Mechanics. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-66110-0.

- Feynman, R., Leighton, R., and Sands, M. (2005). "Chapter 11". The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume I (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-8053-9046-9.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Euclidean vector |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vectors. |

| The Wikibook Waves has a page on the topic of: Vectors |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Vector", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Online vector identities (PDF)

- Introducing Vectors A conceptual introduction (applied mathematics)

- Addition of forces (vectors) Java Applet

- French tutorials on vectors and their application to video games

![\mathbf{a} = [ a_1\ a_2\ a_3 ].](../I/m/c60eaeae8561a2b51a95df339f4f1a94.png)