Poland

Coordinates: 52°N 20°E / 52°N 20°E

| Republic of Poland Rzeczpospolita Polska [a] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Poland Is Not Yet Lost |

||||||

![Location of Poland (dark green)– in Europe (green & dark grey)– in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](../I/m/EU-Poland.svg.png) Location of Poland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Warsaw 52°13′N 21°02′E / 52.217°N 21.033°E | |||||

| Official languages | Polish[1] | |||||

| Regional languages | Kashubian[2] | |||||

| Minority languages | Belarusian, Czech, Lithuanian, German, Slovak, Russian, Ukrainian, Yiddish[2] | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011[3]) | ||||||

| Demonym | ||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| • | President | Andrzej Duda | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Beata Szydło | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||

| • | Lower house | Sejm | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| • | Christianization[b] | 14 April 966 | ||||

| • | Kingdom of Poland | 18 April 1025 | ||||

| • | Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth | 1 July 1569 | ||||

| • | Partition of Poland | 24 October 1795 | ||||

| • | Duchy of Warsaw | 22 July 1807 | ||||

| • | Congress Poland | 9 June 1815 | ||||

| • | Reconstitution of Poland | 11 November 1918 | ||||

| • | Invasion of Poland, World War II | 1 September 1939 | ||||

| • | Communist Poland | 8 April 1945 | ||||

| • | Republic of Poland | 13 September 1989 | ||||

| • | Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 312,679 km2[a] (71st) 120,696.41 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 3.07 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 30 June 2014 estimate | 38,483,957 [4] (34th) | ||||

| • | 2011 census | 38,511,824[5] (34th) | ||||

| • | Density | 123/km2 (83rd) 319.9/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $1.051 trillion[6] (21st) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $27,654 (49th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $508.857 billion[6] (23rd) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $13,390 (54th) | ||||

| Gini (2013) | medium |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | very high · 36th |

|||||

| Currency | Złoty (PLN) | |||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | 48 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | PL | |||||

| Internet TLD | .pl | |||||

| a. | ^a The area of Poland, as given by the Central Statistical Office, is 312,679 km2 (120,726 sq mi), of which 311,888 km2 (120,421 sq mi) is land and 791 km2 (305 sq mi) is internal water surface area.[9] | |||||

| b. | ^b The adoption of Christianity in Poland is seen by many Poles, regardless of their religious affiliation or lack thereof, as one of the most significant events in their country's history, as it was used to unify the tribes in the region.[10] | |||||

Poland (Polish: Polska [ˈpɔlska]), officially the Republic of Poland (Polish: Rzeczpospolita Polska,[a] ![]() listen ), is a country in Central Europe,[11] bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine and Belarus to the east; and the Baltic Sea, Kaliningrad Oblast (a Russian exclave) and Lithuania to the north. The total area of Poland is 312,679 square kilometres (120,726 sq mi),[9] making it the 71st largest country in the world and the 9th largest in Europe. With a population of over 38.5 million people,[9] Poland is the 34th most populous country in the world,[12] the 8th most populous country in Europe and the sixth most populous member of the European Union, as well as the most populous post-communist member of the European Union. Poland is a unitary state divided into 16 administrative subdivisions.

listen ), is a country in Central Europe,[11] bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine and Belarus to the east; and the Baltic Sea, Kaliningrad Oblast (a Russian exclave) and Lithuania to the north. The total area of Poland is 312,679 square kilometres (120,726 sq mi),[9] making it the 71st largest country in the world and the 9th largest in Europe. With a population of over 38.5 million people,[9] Poland is the 34th most populous country in the world,[12] the 8th most populous country in Europe and the sixth most populous member of the European Union, as well as the most populous post-communist member of the European Union. Poland is a unitary state divided into 16 administrative subdivisions.

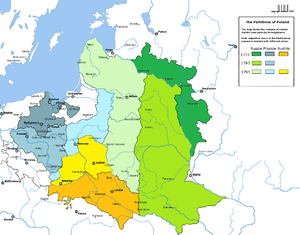

The establishment of a Polish state can be traced back to 966, when Mieszko I,[13] ruler of a territory roughly coextensive with that of present-day Poland, converted to Christianity. The Kingdom of Poland was founded in 1025, and in 1569 it cemented a longstanding political association with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania by signing the Union of Lublin. This union formed the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest and most populous countries of 16th and 17th-century Europe.[14][15] The Commonwealth ceased to exist in the years 1772–1795, when its territory was partitioned among Prussia, the Russian Empire, and Austria. Poland regained its independence (as the Second Polish Republic) at the end of World War I, in 1918.

In September 1939, World War II started with the invasions of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (as part of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact). More than six million Polish citizens died in the war.[16][17] In 1944, a Soviet-backed Polish provisional government was formed which, after a falsified referendum in 1947 took control of the country and Poland became a satellite state[18] of the Soviet Union, as People's Republic of Poland. During the Revolutions of 1989 Poland's Communist government was overthrown and Poland adopted a new constitution establishing itself as a democracy.

Despite the large number of casualties and destruction the country experienced during World War II, Poland managed to preserve much of its cultural wealth. There are 14 heritage sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage[19] and 54 Historical Monuments and many objects of cultural heritage in Poland.

Since the beginning of the transition to a primarily market-based economy that took place in the early 1990s, Poland has achieved a "very high" ranking on the Human Development Index,[20] as well as gradually improving economic freedom.[21] Poland is a democratic country with an advanced high-income economy,[22] a high quality of life and a very high standard of living.[23][24] Moreover, the country is visited by nearly 16 million tourists every year (2013), which makes it one of the most visited countries in the world.[25] Poland is the sixth largest economy in the European Union and among the fastest rising economic states in the world. The country is the sole member nation of the European Union to have escaped a decline in GDP and in recent years was able to "create probably the most varied GDP growth in its history" according to OANDA, a Canadian-based foreign exchange company.[26] Furthermore, according to the Global Peace Index for 2014, Poland is one of the safest countries in the world to live in.[27]

Etymology

The source of the name Poland[28] and the ethnonyms for the Poles[29] include endonyms (the way Polish people refer to themselves and their country) and exonyms (the way other peoples refer to the Poles and their country). Endonyms and most exonyms for Poles and Poland derive from the name of the West Slavic tribe of the Polans (Polanie).

The origin of the name Polanie itself is uncertain. It may derive from such Polish words as pole (field).[30] The early tribal inhabitants denominated it from the nature of the country. Lowlands and low hills predominate throughout the vast region from the Baltic shores to the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. "Between the Alps, Hungary, and the ocean, lies Poland, which is called in their native tongue Campania" (Latin: "Inter Alpes Huniae et Oceanum est Polonia, sic dicta in eorum idiomate quasi Campania") is the description by Gervase of Tilbury in his Otia imperialia ("Recreation for the Emperor") of 1211. In some languages, the exonyms for Poland derive from another tribal name, Lechites (Lechici).

History

Prehistory and protohistory of Poland

Historians have postulated that throughout Late Antiquity, many distinct ethnic groups populated the regions of what is now Poland. The ethnicity and linguistic affiliation of these groups have been hotly debated; the time and route of the original settlement of Slavic peoples in these regions lacks written records and can only be defined as fragmented.[31]

The most famous archaeological find from the prehistory and protohistory of Poland is the Biskupin fortified settlement (now reconstructed as an open-air museum), dating from the Lusatian culture of the early Iron Age, around 700 BC. The Slavic groups who would form Poland migrated to these areas in the second half of the 5th century AD. Up until the creation of Mieszko's state and his subsequent conversion to Christianity in 966 AD, the main religion of Slavic tribes that inhabited the geographical area of present-day Poland was Slavic paganism. After the Baptism of Poland the new religion accepted by the Polish ruler was Catholicism. The transition to Christianity was not a smooth and instantaneous process for the rest of the population as evident from the pagan reaction of the 1030s.[32]

Piast dynasty

Poland began to form into a recognizable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the Piast dynasty. Poland's first historically documented ruler, Mieszko I, accepted Baptism in 966 and adopted Christianity as the new official religion of his subjects. The bulk of the population converted in the course of the next few centuries. In 1000, Boleslaw the Brave, continuing the policy of his father Mieszko, held a Congress of Gniezno and created the metropolis of Gniezno and the dioceses of Kraków, Kołobrzeg, and Wrocław. The pagan unrest however, led to the transfer of the capital to Kraków in 1038 by Casimir I the Restorer.[33]

Prince Bolesław III Wrymouth defeated the King of Germany Henry V in the 1109 Battle of Hundsfeld, writes Gallus Anonymus in his 1118 chronicle.[34] In 1138, Poland fragmented into several smaller duchies when Bolesław divided his lands among his sons. In 1226, Konrad I of Masovia, one of the regional Piast dukes, invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the Baltic Prussian pagans; a decision which led to centuries of warfare with the Knights. Elements of what is called now human rights may be found in early times of the Polish state. The Statute of Kalisz or the General Charter of Jewish Liberties (issued in 1264) introduced numerous right for the Jews in Poland, leading to a nearly autonomous "nation within a nation".[35]

In the middle of 13th-century the Silesian branch of the Piast dynasty (Henry I the Bearded and Henry II the Pious, ruled 1238–1241) almost succeeded in uniting the Polish lands, but the Mongols devastated the country and won the Battle of Legnica where Duke Henry II the Pious died (1241). In 1320, after a number of earlier unsuccessful attempts by regional rulers at uniting the Polish dukedoms, Władysław I consolidated his power, took the throne and became the first king of a reunified Poland. His son, Casimir III (reigned 1333–1370), has a reputation as one of the greatest Polish kings, and gained wide recognition for improving the country's infrastructure.[36][37] Casimir also extended royal protection to Jews, and encouraged their immigration to Poland.[36][38]

The education of Polish society was a goal of rulers as early as the 12th century, and Polish nobility became one of the most educated groups in Europe.[39][40] The library catalogue of the Cathedral Chapter of Kraków dating back to 1110 shows that in the early 12th-century Polish intellectuals had access to European literature.

Casimir III realized that the nation needed a class of educated people, especially lawyers, who could codify the country's laws and administer the courts and offices. His efforts to found an institution of higher learning in Poland were finally rewarded when Pope Urban V granted him permission to open the University of Kraków.

The Golden Liberty of the nobles began to develop under Casimir's rule, when in return for their military support, the king made serious concessions to the aristocrats, finally establishing their status as superior to that of the townsmen, and aiding their rise to power. When Casimir died in 1370 he left no legitimate male heir and, considering his other male descendants either too young or unsuitable, was laid to rest as the last of the nation's Piast rulers.

Poland also became a destination for German, Flemish and to a lesser extent Scottish, Danish and Walloon migrants. The Jewish community also began to settle and flourish in Poland during this era (see History of the Jews in Poland); the same applies in smaller number to Armenians. The Black Death which afflicted most parts of Europe from 1347 to 1351 affected Poland less severely.[41][42]

Jagiellon dynasty

The rule of the Jagiellon dynasty spanned the late Middle Ages and early Modern Era of Polish history. Beginning with the Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło), the Jagiellon dynasty (1386–1572) formed the Polish–Lithuanian union. The partnership brought vast Lithuania-controlled Rus' areas into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for the Poles and Lithuanians, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest political entities in Europe for the next four centuries. In the Baltic Sea region Poland's struggle with the Teutonic Knights continued and included the Battle of Grunwald (1410), where a Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive defeat on the Teutonic Knights, both countries' main adversary, allowing Poland's and Lithuania's territorial expansion into the far north region of Livonia.[43] In 1466, after the Thirteen Years' War, King Casimir IV Jagiellon gave royal consent to the milestone Peace of Thorn, which created the future Duchy of Prussia, a Polish vassal. The Jagiellons at one point also established dynastic control over the kingdoms of Bohemia (1471 onwards) and Hungary.[44][45] In the south Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Tatars (by whom they were attacked on 75 separate occasions between 1474 and 1569),[46] and in the east helped Lithuania fight the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Some historians estimate that Crimean Tatar slave-raiding cost Poland one million of its population from 1494 to 1694.[47]

%3B_A-7%3B_PL-MA%2C_Krak%C3%B3w%2C_Wawel.jpg)

Poland was developing as a feudal state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerful landed nobility. The Nihil novi act adopted by the Polish Sejm (parliament) in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power from the monarch to the Sejm, an event which marked the beginning of the period known as "Golden Liberty", when the state was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility. Protestant Reformation movements made deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time.[48] This tolerance allowed the country to avoid most the religious turmoil that spread over Europe during the late Middle Ages.[48] The European Renaissance evoked in late Jagiellon Poland (kings Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus) a sense of urgency in the need to promote a cultural awakening, and during this period Polish culture and the nation's economy flourished. In 1543 the Pole, Nicolaus Copernicus, an astronomer from Toruń, published his epochal works, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), and thus became the first proponent of a predictive mathematical model confirming heliocentric theory which became the accepted basic model for the practice of modern astronomy. Another major figure associated with the era is classicist poet Jan Kochanowski.[49]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The 1569 Union of Lublin established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a more closely unified federal state with an elective monarchy, but which was governed largely by the nobility, through a system of local assemblies with a central parliament. The Warsaw Confederation (1573) confirmed the religious freedom of all residents of Poland, which was extremely important for the stability of the multiethnic Polish society of the time.[35] Serfdom was banned in 1588.[50] The establishment of the Commonwealth coincided with a period of stability and prosperity in Poland, with the union thereafter becoming a European power and a major cultural entity, occupying approximately one million square kilometers of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as an agent for the dissemination of 'Western culture' through Polonization in modern-day Ukraine, Belarus and Western Russia. Poland suffered from a number of dynastic crises during the reigns of the Vasa kings Sigismund III and Władysław IV and found itself engaged in major conflicts with Russia, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, as well as a series of minor Cossack uprisings.[51] In 1610 Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski seized Moscow after winning the Battle of Klushino.

From the middle of the 17th century, the nobles' democracy, suffering from internal disorder, gradually declined, thus leaving the once powerful Commonwealth vulnerable to foreign intervention. Starting in 1648, the Cossack Khmelnytsky Uprising engulfed the south and east eventually leaving Ukraine divided, with the eastern part, lost by the Commonwealth, becoming a dependency of the Tsardom of Russia. This was followed by the 'Deluge', a Swedish invasion, which marched through the Polish heartlands and damaged Poland's population, culture and infrastructure. Around four million of Poland's eleven million population died in famines and epidemics in this period.[52] However, under John III Sobieski the Commonwealth's military prowess was re-established, and in 1683 Polish forces played a major part in relieving Vienna of a Turkish siege which was being conducted by Kara Mustafa.

Sobieski's reign marked the end of the nation's golden-era. Finding itself subjected to almost constant warfare and suffering enormous population losses as well as massive damage to its economy, the Commonwealth fell into decline. The government became ineffective as a result of large-scale internal conflicts (e.g. Lubomirski Rebellion against John II Casimir and rebellious confederations) and corrupted legislative processes. The nobility fell under the control of a handful of magnats, and this, compounded with two relatively weak kings of the Saxon Wettin dynasty, Augustus II and Augustus III, as well as the rise of Russia and Prussia after the Great Northern War only served to worsen the Commonwealth's plight. Despite this The Commonwealth-Saxony personal union gave rise to the emergence of the Commonwealth's first reform movement, and laid the foundations for the Polish Enlightenment.[53]

During the later part of the 18th century, the Commonwealth made attempts to implement fundamental internal reforms; with the second half of the century bringing a much improved economy, significant population growth and far-reaching progress in the areas of education, intellectual life, art, and especially toward the end of the period, evolution of the social and political system. The most populous capital city of Warsaw replaced Gdańsk (Danzig) as the leading centre of commerce, and the role of the more prosperous townsfolk increased.

The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław II August, a refined and worldly aristocrat connected to a major magnate faction, to the monarchy. However, a one-time lover of Empress Catherine II of Russia, the new king spent much of his reign torn between his desire to implement reforms necessary to save his nation, and his perceived necessity to remain in a relationship with his Russian sponsor. This led to the formation of the 1768 Bar Confederation, a szlachta rebellion directed against Russia and the Polish king that fought to preserve Poland's independence and the szlachta's traditional privileges. Attempts at reform provoked the union's neighbours, and in 1772 the First Partition of the Commonwealth by Russia, Austria and Prussia took place; an act which the "Partition Sejm", under considerable duress, eventually "ratified" fait accompli.[54] Disregarding this loss, in 1773 the king established the Commission of National Education, the first government education authority in Europe. Corporal punishment of children was officially prohibited in 1783 as first in the world at all schools.

The Great Sejm convened by Stanisław II August in 1788 successfully adopted the 3 May Constitution, the first set of modern supreme national laws in Europe. However, this document, accused by detractors of harbouring revolutionary sympathies, generated strong opposition from the Commonwealth's nobles and conservatives as well as from Catherine II, who, determined to prevent the rebirth of a strong Commonwealth set about planning the final dismemberment of the Polish-Lithuanian state. Russia was aided in achieving its goal when the Targowica Confederation, an organisation of Polish nobles, appealed to the Empress for help. In May 1792 Russian forces crossed the Commonwealth's frontier, thus beginning the Polish-Russian War.

The defensive war fought by the Poles ended prematurely when the King, convinced of the futility of resistance, capitulated and joined the Targowica Confederation. The Confederation then took over the government. Russia and Prussia, fearing the mere existence of a Polish state, arranged for, and in 1793 executed, the Second Partition of the Commonwealth, which left the country deprived of so much territory that it was practically incapable of independent existence. Eventually, in 1795, following the failed Kościuszko Uprising, the Commonwealth was partitioned one last time by all three of its more powerful neighbours, and with this, effectively ceased to exist.[55]

The Age of Partitions

Poles rebelled several times against the partitioners, particularly near the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. An unsuccessful attempt at defending Poland's sovereignty took place in 1794 during the Kościuszko Uprising, where a popular and distinguished general Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who had served under Washington in America, led Polish insurgents against numerically superior Russian forces. Despite the victory at the Battle of Racławice, his ultimate defeat ended Poland's independent existence for 123 years.[56] In 1807, Napoleon I of France temporarily recreated a Polish state as a satellite Duchy of Warsaw, but after the failed Napoleonic Wars, Poland was again split between the victorious Allies at the Congress of Vienna of 1815.[57] The eastern part was ruled by the Russian tsar as a Congress Kingdom, which had a very liberal constitution. However, the tsars reduced Polish freedoms, and Russia annexed the country in virtually all but name. Thus in the latter half of the 19th century, only Austrian-ruled Galicia, and particularly the Free City of Kraków, created good environment for free Polish cultural life to flourish.

Throughout the period of the partitions, political and cultural repression of the Polish nation led to the organisation of a number of uprisings against the authorities of the occupying Russian, Prussian and Austrian governments. Notable among these are the November Uprising of 1830 and January Uprising of 1863, both of which were attempts to free Poland from the rule of tsarist Russia. The November uprising began on 29 November 1830 in Warsaw when, led by Lieutenant Piotr Wysocki, young non-commissioned officers at the Imperial Russian Army's military academy in that city revolted. They were joined by large segments of Polish society, and together forced Warsaw's Russian garrison to withdraw north of the city.

Over the course of the next seven months, Polish forces successfully defeated the Russian armies of Field Marshal Hans Karl von Diebitsch and a number of other Russian commanders; however, finding themselves in a position unsupported by any other foreign powers, save distant France and the newborn United States, and with Prussia and Austria refusing to allow the import of military supplies through their territories, the Poles accepted that the uprising was doomed to failure. Upon the surrender of Warsaw to General Ivan Paskievich, many Polish troops, feeling they could not go on, withdrew into Germany and there laid down their arms. Poles would have to wait another 32 years for another opportunity to free their homeland.

When in January 1863 a new Polish uprising against Russian rule began, it did so as a spontaneous protest by young Poles against conscription into the Imperial Russian Army. However, the insurrectionists, despite being joined by high-ranking Polish-Lithuanian officers and numerous politicians, were still severely outnumbered and lacking in foreign support. They were forced to resort to guerrilla warfare tactics and failed to win any major military victories. Afterwards no major uprising was witnessed in the Russian-controlled Congress Poland, and Poles resorted instead to fostering economic and cultural self-improvement.

Despite the political unrest experienced during the partitions, Poland did benefit from large-scale industrialisation and modernisation programs, instituted by the occupying powers, which helped it develop into a more economically coherent and viable entity. This was particularly true in the Greater Poland, Pomerania and Warmia annexed by Prussia (later becoming a part of the German Empire); an area which eventually, thanks largely to the Greater Poland Uprising, was reconstituted as a part of the Second Polish Republic and became one of its most productive regions.

Reconstitution of Poland

During World War I, all the Allies agreed on the reconstitution of Poland that United States President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed in Point 13 of his Fourteen Points. A total of 2 million Polish troops fought with the armies of the three occupying powers, and 450,000 died. Shortly after the armistice with Germany in November 1918, Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic (II Rzeczpospolita Polska). It reaffirmed its independence after a series of military conflicts, the most notable being the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921) when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on the Red Army at the Battle of Warsaw, an event which is considered to have halted the advance of Communism into Europe and forced Vladimir Lenin to rethink his objective of achieving global socialism. Nowadays the event is often referred to as the "Miracle at the Vistula".[58]

During this period, Poland successfully managed to fuse the territories of the three former partitioning powers into a cohesive nation state. Railways were restructured to direct traffic towards Warsaw instead of the former imperial capitals, a new network of national roads was gradually built up and a major seaport was opened on the Baltic Coast, so as to allow Polish exports and imports to bypass the politically charged Free City of Danzig.

The inter-war period heralded in a new era of Polish politics. Whilst Polish political activists had faced heavy censorship in the decades up until the First World War, the country now found itself trying to establish a new political tradition. For this reason, many exiled Polish activists, such as Ignacy Paderewski (who would later become Prime Minister) returned home to help; a significant number of them then went on to take key positions in the newly formed political and governmental structures. Tragedy struck in 1922 when Gabriel Narutowicz, inaugural holder of the Presidency, was assassinated at the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw by painter and right-wing nationalist Eligiusz Niewiadomski.[59]

The 1926 May Coup of Józef Piłsudski turned rule of the Second Polish Republic over to the Sanacja movement. By the 1930s Poland had become increasingly authoritarian; a number of 'undesirable' political parties, such as the Polish Communists, had been banned and following Piłsudski's death, the regime, unable to appoint a new leader, began to show its inherent internal weaknesses and unwillingness to cooperate in any way with other political parties.

As result of the Munich Agreement of 1 October 1938, Poland invaded and occupied the Zaolzie Region of Czechoslovakia.

World War II

The formal beginning of World War II was marked by the Nazi German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, followed by the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September in violation of the Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact. On 28 September 1939 Warsaw capitulated. As agreed earlier in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was split into two occupied zones, one subdivided by Nazi Germany, while the other, including all of eastern Kresy fell under the control of the Soviet Union. In 1939–1941, the Soviets had deported hundreds of thousands of Poles out to the most distant parts of the Soviet Union. The Soviet NKVD secretly executed thousands of Polish prisoners of war (inter alia Katyn massacre) ahead of the Operation Barbarossa.[60] German planners had in November 1939 called for "the complete destruction" of all Poles and their fate, as well as many other Slavs, was outlined in genocidal Generalplan Ost.[61]

All in all, Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution to the Allied war effort, after the Soviets, the British, and the Americans.[b] Polish troops fought under the command of both the Polish Government in Exile in the theatre of war west of Germany and under Soviet leadership in the theatre of war east of Germany. The Polish expeditionary corps, which was controlled by the exiled pre-war government based in London, played an important role in the Italian and North African Campaigns.[62][63] They are particularly well remembered for their conduct at the Battle of Monte Cassino, a conflict which culminated in the raising of a Polish flag over the ruins of the mountain-top abbey by the 12th Podolian Uhlans. The Polish forces in the theatre of war east of Germany were commanded by Lieutenant General Władysław Anders who had received his command from Prime Minister of the exiled government Władysław Sikorski. On the east of Germany, the Soviet-backed Polish 1st Army distinguished itself in the battles for Berlin and Warsaw,[64] although its actions in support of the latter have often been criticized.

Polish servicemen were also active in the theatres of naval and air warfare; during the Battle of Britain Polish squadrons such as the No. 303 "Kościuszko" fighter squadron[65] achieved considerable success, and by the end of the war the exiled Polish Air Forces could claim 769 confirmed kills. Meanwhile, the Polish Navy was active in the protection of convoys in the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean.[66]

In addition to the organised units of the 1st Army and the Forces in the Nazi-occupied Europe, the domestic underground resistance movement, the Armia Krajowa, or Home Army, fought to free Poland from German occupation and establish an independent Polish state. The wartime resistance movement in Poland was one of the three largest resistance movements of the entire war,[c] and encompassed an unusually broad range of clandestine activities, which essentially functioned as an underground state complete with degree-awarding universities and a court system.[67] The resistance was, however, largely loyal to the exiled government and generally resented the idea of a communist Poland; for this reason, in the summer of 1944 they initiated Operation Tempest, of which the Warsaw Uprising that begun on 1 August 1944 was the best known operation.[68][69] The objective of the uprising was to drive the German occupiers from the city and help with the larger fight against Germany and the Axis powers. However, secondary motives for the uprising sought to see Warsaw liberated before the Soviets could reach the capital, so as to underscore Polish sovereignty by empowering the Polish Underground State before the Soviet-backed Polish Committee of National Liberation could assume control. However, a lack of available allied military aid and Stalin's reluctance to allow the 1st Army to help their fellow countrymen take the city, led to the uprising's failure and subsequent planned destruction of the city.

During the war, German forces under direct order from Adolf Hitler set up six major extermination camps, all of which operated in the heart of Poland. They included the notorious Treblinka and Auschwitz killing grounds. This allowed the Germans to transport the condemned Jews away from public eye in the Third Reich or across occupied Europe and – under the guise of resettlement – murder them in the General Government and in brand new Warthegau among other annexed areas. The Nazi crimes against the Polish nation claimed the lives of 2.7 to 2.9 million Polish Jews,[70] and 2.77 million ethnic Poles,[71] including Polish intelligentsia, doctors, lawyers, nobility, priests and numerous others. Since 3,5 million Jews lived in pre-war Poland, Jewish victims make up the largest percentage of all victims of the Nazis' extermination program. It is estimated that, of pre-war Poland's Jewry, approximately 90% were killed. Throughout the occupation, many members of the Armia Krajowa, supported by the Polish government in exile, and millions of ordinary Poles – at great risk to themselves and their families – engaged in rescuing Jews from the Nazi Germans. Grouped by nationality, Poles represent the largest number of people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. To date, 6,394 Poles have been awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations by the State of Israel–more than any other nation.[72] Some estimates put the number of Poles involved in rescue efforts at up to 3 million, and credit Poles with sheltering up to 450,000 Jews.

At the war's conclusion in 1945, Poland's borders were shifted westwards, resulting in considerable territorial losses. Most of the Polish inhabitants of Kresy were expelled along the Curzon Line in accordance with Stalin's agreements.[73] The western border was moved to the Oder-Neisse line. As a result, Poland's territory was reduced by 20%, or 77,500 square kilometres (29,900 sq mi). The shift forced the migration of millions of other people, most of whom were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews.[74] Of all the countries involved in the war, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: over 6 million perished – nearly one-fifth of Poland's population — half of them Polish Jews.[16][17][75][76] Over 90% of deaths were non-military in nature. Population numbers did not recover until the 1970s. An estimated 600,000 Soviet soldiers died in conquering Poland from German rule.[77]

Postwar communist Poland

At the insistence of Joseph Stalin, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a new provisional pro-Communist coalition government in Moscow, which ignored the Polish government-in-exile based in London; a move which angered many Poles who considered it a betrayal by the Allies. In 1944, Stalin had made guarantees to Churchill and Roosevelt that he would maintain Poland's sovereignty and allow democratic elections to take place. However, upon achieving victory in 1945, the elections organized by the occupying Soviet authorities were falsified and were used to provide a veneer of 'legitimacy' for Soviet hegemony over Polish affairs. The Soviet Union instituted a new communist government in Poland, analogous to much of the rest of the Eastern Bloc. As elsewhere in Communist Europe the Soviet occupation of Poland met with armed resistance from the outset which continued into the fifties.

Despite widespread objections, the new Polish government accepted the Soviet annexation of the pre-war eastern regions of Poland[78] (in particular the cities of Wilno and Lwów) and agreed to the permanent garrisoning of Red Army units on Poland's territory. Military alignment within the Warsaw Pact throughout the Cold War came about as a direct result of this change in Poland's political culture and in the European scene came to characterise the full-fledged integration of Poland into the brotherhood of communist nations.

The People's Republic of Poland (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) was officially proclaimed in 1952. In 1956 after the death of Bolesław Bierut, the régime of Władysław Gomułka became temporarily more liberal, freeing many people from prison and expanding some personal freedoms. A similar situation repeated itself in the 1970s under Edward Gierek, but most of the time persecution of anti-communist opposition groups persisted. Despite this, Poland was at the time considered to be one of the least oppressive states of the Soviet Bloc.[79]

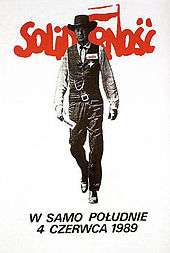

Labour turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity" ("Solidarność"), which over time became a political force. Despite persecution and imposition of martial law in 1981, it eroded the dominance of the Polish United Workers' Party and by 1989 had triumphed in Poland's first partially free and democratic parliamentary elections since the end of the Second World War. Lech Wałęsa, a Solidarity candidate, eventually won the presidency in 1990. The Solidarity movement heralded the collapse of communist regimes and parties across Europe.

Present-day Poland

A shock therapy programme, initiated by Leszek Balcerowicz in the early 1990s enabled the country to transform its socialist-style planned economy into a market economy. As with other post-communist countries, Poland suffered slumps in social and economic standards,[80] but it became the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989 GDP levels, which it achieved by 1995 largely thanks to its booming economy.[81][82]

Most visibly, there were numerous improvements in human rights, such as the freedom of speech, internet freedom (no censorship), civil liberties (1st class) and political rights (1st class), according to Freedom House. In 1991, Poland became a member of the Visegrád Group and joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance in 1999 along with the Czech Republic and Hungary. Poles then voted to join the European Union in a referendum in June 2003, with Poland becoming a full member on 1 May 2004. Poland joined the Schengen Area in 2007, as a result of which, the country's borders with other member states of the European Union have been dismantled, allowing for full freedom of movement within most of the EU.[83] In contrast to this, a section of Poland's eastern border now comprises the external EU border with Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. That border has become increasingly well protected, and has led in part to the coining of the phrase 'Fortress Europe', in reference to the seeming 'impossibility' of gaining entry to the EU for citizens of the former Soviet Union.

.jpg)

Poland has been one of the most prominent voices of establishing a common European Armed Forces, with Poland's Premier along with Chancellor Angela Merkel and President François Hollande (collectively also part of Weimar Triangle) taking steps to negotiate such a deal, in hope of drastically reducing dependence on NATO and increasing readiness.[84] Poland has already built several commands of a common battle group with Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, with a total of 12,000 troops ready for deployment. Poland is seeking to build more battle groups with Lithuania and Ukraine. These battle groups have vowed to serve under the European Union, and not NATO.[85] Eurosceptics criticize such moves as further unnecessary integration and a new major step towards a federalized European Union under one government. Military integration is judged to be the most significant step after a monetary union.

On 10 April 2010, the President of the Republic of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, along with 89 other high-ranking Polish officials died in a plane crash near Smolensk, Russia. The president's party were on their way to attend an annual service of commemoration for the victims of the Katyń massacre when the tragedy took place.

In 2011, the Presidency of the Council of the European Union responsible for the functioning of the Council was awarded to Poland. The same year parliamentary elections took place to both the Senate and the Sejm. They were won by the ruling Civic Platform. Poland joined European Space Agency in 2012, as well as organised the UEFA Euro 2012 (along with Ukraine). In 2013, Poland also became a member of the Development Assistance Committee. In 2014 the Prime Minister of Poland, Donald Tusk, was elected President of the European Council.

Geography

Poland's territory extends across several geographical regions, between latitudes 49° and 55° N, and longitudes 14° and 25° E. In the north-west is the Baltic seacoast, which extends from the Bay of Pomerania to the Gulf of Gdańsk. This coast is marked by several spits, coastal lakes (former bays that have been cut off from the sea), and dunes. The largely straight coastline is indented by the Szczecin Lagoon, the Bay of Puck, and the Vistula Lagoon. The centre and parts of the north lie within the North European Plain.

Rising above these lowlands is a geographical region comprising the four hilly districts of moraines and moraine-dammed lakes formed during and after the Pleistocene ice age. These lake districts are the Pomeranian Lake District, the Greater Polish Lake District, the Kashubian Lake District, and the Masurian Lake District. The Masurian Lake District is the largest of the four and covers much of north-eastern Poland. The lake districts form part of the Baltic Ridge, a series of moraine belts along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea.

South of the Northern European Lowlands lie the regions of Lusatia, Silesia and Masovia, which are marked by broad ice-age river valleys. Farther south lies the Polish mountain region, including the Sudetes, the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, and the Carpathian Mountains, including the Beskids. The highest part of the Carpathians is the Tatra Mountains, along Poland's southern border.

Geology

The geological structure of Poland has been shaped by the continental collision of Europe and Africa over the past 60 million years and, more recently, by the Quaternary glaciations of northern Europe. Both processes shaped the Sudetes and the Carpathian Mountains. The moraine landscape of northern Poland contains soils made up mostly of sand or loam, while the ice age river valleys of the south often contain loess. The Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, the Pieniny, and the Western Tatras consist of limestone, while the High Tatras, the Beskids, and the Karkonosze are made up mainly of granite and basalts. The Polish Jura Chain is one of the oldest mountain ranges on earth.

Poland has 70 mountains over 2,000 metres (6,600 feet) in elevation, all in the Tatras. The Polish Tatras, which consist of the High Tatras and the Western Tatras, is the highest mountain group of Poland and of the entire Carpathian range. In the High Tatras lies Poland's highest point, the north-western summit of Rysy, 2,499 metres (8,199 ft) in elevation. At its foot lies the mountain lakes of Czarny Staw pod Rysami (Black Lake below Mount Rysy), and Morskie Oko (the Marine Eye).[86]

The second highest mountain group in Poland is the Beskids, whose highest peak is Babia Góra, at 1,725 metres (5,659 ft). The next highest mountain groups is the Karkonosze in the Sudetes, whose highest point is Śnieżka, at 1,603 metres (5,259 ft); Śnieżnik Mountains whose highest point is Śnieżnik, at 1,425 metres (4,675 ft).

Tourists also frequent the Bieszczady Mountains in the far southeast of Poland, whose highest point in Poland is Tarnica, with an elevation of 1,346 metres (4,416 ft), Gorce Mountains in Gorce National Park, whose highest point is Turbacz, with elevations 1,310 metres (4,298 ft), and the Pieniny in Pieniny National Park, whose highest point is Wysokie Skałki (Wysoka), with elevations 1,050 metres (3,445 ft). The lowest point in Poland – at 2 metres (6.6 ft) below sea level – is at Raczki Elbląskie, near Elbląg in the Vistula Delta.

The only desert located in Poland stretches over the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie (the Coal Fields of Dąbrowa) region. It is called the Błędów Desert, located in the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland. It has a total area of 32 square kilometres (12 sq mi). It is one of only five natural deserts in Europe. But also, it is the warmest desert that appears at this latitude. Błędów Desert was created thousands of years ago by a melting glacier. The specific geological structure has been of big importance. The average thickness of the sand layer is about 40 metres (131 ft), with a maximum of 70 metres (230 ft), which made the fast and deep drainage very easy.

The Baltic Sea activity in Słowiński National Park created sand dunes which in the course of time separated the bay from the sea. As waves and wind carry sand inland the dunes slowly move, at a rate of 3 to 10 metres (9.8 to 32.8 ft) meters per year. Some dunes are quite high – up to 30 metres (98 ft). The highest peak of the park – Rowokol (115 metres or 377 feet above sea level) — is also an excellent observation point.

Waters

.jpg)

The longest rivers are the Vistula (Polish: Wisła), 1,047 kilometres (651 mi) long; the Oder (Polish: Odra) which forms part of Poland's western border, 854 kilometres (531 mi) long; its tributary, the Warta, 808 kilometres (502 mi) long; and the Bug, a tributary of the Vistula, 772 kilometres (480 mi) long. The Vistula and the Oder flow into the Baltic Sea, as do numerous smaller rivers in Pomerania.

The Łyna and the Angrapa flow by way of the Pregolya to the Baltic, and the Czarna Hańcza flows into the Baltic through the Neman. While the great majority of Poland's rivers drain into the Baltic Sea, Poland's Beskids are the source of some of the upper tributaries of the Orava, which flows via the Váh and the Danube to the Black Sea. The eastern Beskids are also the source of some streams that drain through the Dniester to the Black Sea.

Poland's rivers have been used since early times for navigation. The Vikings, for example, traveled up the Vistula and the Oder in their longships. In the Middle Ages and in early modern times, when the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was the breadbasket of Europe;[87] the shipment of grain and other agricultural products down the Vistula toward Gdańsk and onward to other parts of Europe took on great importance.[87]

With almost ten thousand closed bodies of water covering more than 1 hectare (2.47 acres) each, Poland has one of the highest numbers of lakes in the world. In Europe, only Finland has a greater density of lakes.[88] The largest lakes, covering more than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi), are Lake Śniardwy and Lake Mamry in Masuria, and Lake Łebsko and Lake Drawsko in Pomerania.

In addition to the lake districts in the north (in Masuria, Pomerania, Kashubia, Lubuskie, and Greater Poland), there is also a large number of mountain lakes in the Tatras, of which the Morskie Oko is the largest in area. The lake with the greatest depth—of more than 100 metres (328 ft)—is Lake Hańcza in the Wigry Lake District, east of Masuria in Podlaskie Voivodeship.

Among the first lakes whose shores were settled are those in the Greater Polish Lake District. The stilt house settlement of Biskupin, occupied by more than one thousand residents, was founded before the 7th century BC by people of the Lusatian culture.

Lakes have always played an important role in Polish history and continue to be of great importance to today's modern Polish society. The ancestors of today's Poles, the Polanie, built their first fortresses on islands in these lakes. The legendary Prince Popiel ruled from Kruszwica tower erected on the Lake Gopło.[89] The first historically documented ruler of Poland, Duke Mieszko I, had his palace on an island in the Warta River in Poznań. Nowadays the Polish lakes provide a location for the pursuit of water sports such as yachting and wind-surfing.

The Polish Baltic coast is approximately 528 kilometres (328 mi) long and extends from Świnoujście on the islands of Usedom and Wolin in the west to Krynica Morska on the Vistula Spit in the east. For the most part, Poland has a smooth coastline, which has been shaped by the continual movement of sand by currents and winds. This continual erosion and deposition has formed cliffs, dunes, and spits, many of which have migrated landwards to close off former lagoons, such as Łebsko Lake in Słowiński National Park.

Prior to the end of the Second World War and subsequent change in national borders, Poland had only a very small coastline; this was situated at the end of the 'Polish Corridor', the only internationally recognised Polish territory which afforded the country access to the sea. However, after World War II, the redrawing of Poland's borders and resulting 'shift' of the country's borders left it with an expanded coastline, thus allowing for far greater access to the sea than was ever previously possible. The significance of this event, and importance of it to Poland's future as a major industrialised nation, was alluded to by the 1945 Wedding to the Sea.

The largest spits are Hel Peninsula and the Vistula Spit. The largest Polish Baltic island is Wolin. The largest sea harbours are Szczecin, Świnoujście, Gdańsk, Gdynia, Police and Kołobrzeg. The main coastal resorts are Świnoujście, Międzyzdroje, Kołobrzeg, Łeba, Sopot, Władysławowo and the Hel Peninsula.

Land use

Poland is the fourth most forested country in Europe. Forests cover about 30.5% of Poland's land area based on international standards.[90] Its overall percentage is still increasing. Forests of Poland is managed by the national program of reforestation (KPZL), aiming at an increase of forest-cover to 33% in 2050. The richness of Polish forest (per SoEF 2011 statistics) is more than twice as high as European average (with Germany and France at the top), containing 2.304 billion cubic metres of trees.[90] The largest forest complex in Poland is Lower Silesian Wilderness.

More than 1% of Poland's territory, 3,145 square kilometres (1,214 sq mi), is protected within 23 Polish national parks. Three more national parks are projected for Masuria, the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, and the eastern Beskids. In addition, wetlands along lakes and rivers in central Poland are legally protected, as are coastal areas in the north. There are over 120 areas designated as landscape parks, along with numerous nature reserves and other protected areas (e.g. Natura 2000).

Since Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004, Polish agriculture has performed extremely well and the country has over two million private farms.[91][92] It is the leading producer in Europe of potatoes and rye (world's second largest in 1989) the world's largest producer of triticale,[93] and one of the more important producers of barley, oats, sugar beets, flax, and fruits.It is the European Union's fourth largest supplier of pigmeat after Germany, Spain and France.[94] The government continues debating further agricultural reform and pursuing the option of auctioning off large tracts of state-owned agricultural land.

Biodiversity

.

Phytogeographically, Poland belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of Poland belongs to three Palearctic Ecoregions of the continental forest spanning Central and Northern European temperate broadleaf and mixed forest ecoregions as well as the Carpathian montane conifer forest.

Many animals that have since died out in other parts of Europe still survive in Poland, such as the wisent in the ancient woodland of the Białowieża Forest and in Podlaskie. Other such species include the brown bear in Białowieża, in the Tatras, and in the Beskids, the gray wolf and the Eurasian lynx in various forests, the moose in northern Poland, and the beaver in Masuria, Pomerania, and Podlaskie.

In the forests, one also encounters game animals, such as red deer, roe deer and wild boars. In eastern Poland there are a number of ancient woodlands, like Białowieża forest, that have never been cleared or have been disturbed much by people. There are also large forested areas in the mountains, Masuria, Pomerania, Lubusz Land and Lower Silesia.

Poland is the most important breeding ground for a variety of European migratory birds.[96] Out of all of the migratory birds who come to Europe for the summer, one quarter of the global population of white storks (40,000 breeding pairs) live in Poland,[97] particularly in the lake districts and the wetlands along the Biebrza, the Narew, and the Warta, which are part of nature reserves or national parks.

Climate

The climate is mostly temperate throughout the country. The climate is oceanic in the north and west and becomes gradually warmer and continental towards the south and east. Summers are generally warm, with average temperatures between 18 and 30 °C (64.4 and 86.0 °F) depending on a region. Winters are rather cold, with average temperatures around 3 °C (37.4 °F) in the northwest and −6 °C (21 °F) in the northeast. Precipitation falls throughout the year, although, especially in the east; winter is drier than summer.[98]

The warmest region in Poland is Lower Silesia located in south-western Poland where temperatures in the summer average between 24 and 32 °C (75 and 90 °F) but can go as high as 34 to 39 °C (93.2 to 102.2 °F) on some days in the warmest month of July and August. The warmest cities in Poland are Tarnów, which is situated in Lesser Poland and Wrocław, which is located in Lower Silesia. The average temperatures in Wrocław are 20 °C (68 °F) in the summer and 0 °C (32.0 °F) in the winter, but Tarnów has the longest summer in all of Poland, which lasts for 115 days, from mid-May to mid-September. The coldest region of Poland is in the northeast in the Podlaskie Voivodeship near the border of Belarus and Lithuania. Usually the coldest city is Suwałki. The climate is affected by cold fronts which come from Scandinavia and Siberia. The average temperature in the winter in Podlaskie ranges from −6 to −4 °C (21 to 25 °F).

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warsaw | 23/13 | 74/55 | 0/−5 | 32/23 |

| Kraków | 24/13 | 75/56 | 1/−5 | 34/23 |

| Łódź | 24/14 | 75/57 | 0/−5 | 33/25 |

| Wrocław | 25/13 | 77/55 | 3/−4 | 37/25 |

| Poznań | 24/15 | 76/60 | 2/–4 | 36/23 |

| Gdańsk/Gdynia | 22/15 | 73/58 | 2/−3 | 35/26 |

Politics

Poland is a representative democracy, with a president as a head of state, whose current constitution dates from 1997. Poland is a peaceful country. The government structure centers on the Council of Ministers, led by a prime minister. The president appoints the cabinet according to the proposals of the prime minister, typically from the majority coalition in the Sejm. The president is elected by popular vote every five years. The president is Andrzej Duda and the current prime minister is Beata Szydło.

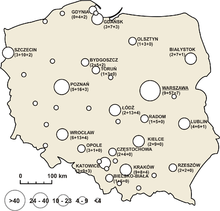

Polish voters elect a bicameral parliament consisting of a 460-member lower house (Sejm) and a 100-member Senate (Senat). The Sejm is elected under proportional representation according to the d'Hondt method, a method similar to that used in many parliamentary political systems. The Senat, on the other hand, is elected under the first-past-the-post voting method, with one senator being returned from each of the 100 constituencies.

With the exception of ethnic minority parties, only candidates of political parties receiving at least 5% of the total national vote can enter the Sejm. When sitting in joint session, members of the Sejm and Senat form the National Assembly (the Zgromadzenie Narodowe). The National Assembly is formed on three occasions: when a new President takes the oath of office; when an indictment against the President of the Republic is brought to the State Tribunal (Trybunał Stanu); and when a president's permanent incapacity to exercise his duties due to the state of his health is declared. To date only the first instance has occurred.

The judicial branch plays an important role in decision-making. Its major institutions include the Supreme Court of the Republic of Poland (Sąd Najwyższy); the Supreme Administrative Court of the Republic of Poland (Naczelny Sąd Administracyjny); the Constitutional Tribunal of the Republic of Poland (Trybunał Konstytucyjny); and the State Tribunal of the Republic of Poland (Trybunał Stanu). On the approval of the Senat, the Sejm also appoints the ombudsman or the Commissioner for Civil Rights Protection (Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich) for a five-year term. The ombudsman has the duty of guarding the observance and implementation of the rights and liberties of Polish citizens and residents, of the law and of principles of community life and social justice.

Law

The Constitution of Poland is the supreme law in contemporary Poland, and the Polish legal system is based on the principle of civil rights, governed by the code of Civil Law. Historically, the most famous Polish legal act is the Constitution of 3 May 1791. Historian Norman Davies describes it as the first of its kind in Europe.[100] The Constitution was instituted as a Government Act (Polish: Ustawa rządowa) and then adopted on 3 May 1791 by the Sejm of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Primarily, it was designed to redress long-standing political defects of the federative Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and its Golden Liberty. Previously only the Henrican articles signed by each of Poland's elected kings could perform the function of a set of basic laws.

The new Constitution introduced political equality between townspeople and the nobility (szlachta), and placed the peasants under the protection of the government. The Constitution abolished pernicious parliamentary institutions such as the liberum veto, which at one time had placed the sejm at the mercy of any deputy who might choose, or be bribed by an interest or foreign power, to have rescinded all the legislation that had been passed by that sejm. The 3 May Constitution sought to supplant the existing anarchy fostered by some of the country's reactionary magnates, with a more egalitarian and democratic constitutional monarchy. The adoption of the constitution was treated as a threat by Poland's neighbours.[101] In response Prussia, Austria and Russia formed an anti-Polish alliance and over the next decade collaborated with one another to partition their weaker neighbour and destroyed the Polish state. In the words of two of its co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, the constitution represented "the last will and testament of the expiring Fatherland." Despite this, its text influenced many later democratic movements across the globe.[102] In Poland, freedom of expression is guaranteed by the Article 25 (section I. The Republic) and Article 54 (section II. The Freedoms, Rights and Obligations of Persons and Citizens) of the Constitution of Poland.

Feminism in Poland started in the 1800s in the age of the foreign Partitions. Poland's precursor of feminism, Narcyza Żmichowska, founded a group of Suffragettes in 1842. Prior to the last Partition in 1795, tax-paying females were allowed to take part in political life. Since 1918, following the return to independence, all women could vote. Poland was the 15th (12th sovereign) country to introduce universal women's suffrage. Nevertheless, there is a number of issues concerning women in modern-day Poland such as the abortion rights (formally allowed only in special circumstances) and the "glass ceiling".[103][104] Homosexuality in Poland was confirmed as legal in 1932. Poland recognises gender change.[105]

A 2010 article in Rzeczpospolita reported that in a 2008 study three-quarters of Poles were against gay marriage or the adoption of children by gay couples in accordance with the Catholic teachings.[106] The same study revealed that 66% of respondents were opposed to Pride parade as the demonstration of a way of life, and 69% believed that gay people should not show their sexual orientation in public.[107] Poland belongs to the group of 'Tier 1'[108] countries in Trafficking in Persons Report. Trafficking women is 'illegal and rare' (top results worldwide).[109]

Poland's current constitution was adopted by the National Assembly of Poland on 2 April 1997, approved by a national referendum on 25 May 1997, and came into effect on 17 October 1997. It guarantees a multi-party state, the freedoms of religion, speech and assembly, and specifically casts off many Communist ideals to create a 'free market economic system'. It requires public officials to pursue ecologically sound public policy and acknowledges the inviolability of the home, the right to form trade unions, and to strike, whilst at the same time prohibiting the practices of forced medical experimentation, torture and corporal punishment.

Foreign relations

In recent years, Poland has extended its responsibilities and position in European and international affairs, supporting and establishing friendly relations with other European nations and a large number of 'developing' countries.

Poland is a member of the European Union, NATO, the UN, the World Trade Organization, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), European Economic Area, International Energy Agency, Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, International Atomic Energy Agency, European Space Agency, G6, Council of the Baltic Sea States, Visegrád Group, Weimar Triangle and Schengen Agreement.

In 1994, Poland became an associate member of the European Union (EU) and its defensive arm, the Western European Union (WEU), having submitted preliminary documentation for full membership in 1996, it formally joined the European Union in May 2004, along with the other members of the Visegrád group. In 1996, Poland achieved full OECD membership, and at the 1997 Madrid Summit was invited to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) in the first wave of policy enlargement finally becoming a full member of NATO in March 1999.

As changes since the fall of Communism in 1989 have redrawn the map of Europe, Poland has tried to forge strong and mutually beneficial relationships with its seven new neighbours, this has notably included signing 'friendship treaties' to replace links severed by the collapse of the Warsaw Pact. The Poles have forged special relationships with Lithuania and particularly Ukraine,[110] with whom they co-hosted the UEFA Euro 2012 football tournament, in an effort to firmly anchor these countries within the Western world and provide them with an alternative to aligning themselves with the Russian Federation respectively. Despite many positive developments in the region, Poland has found itself in a position where it must seek to defend the rights of ethnic Poles living in the former Soviet Union; this is particularly true of Belarus, where in 2005 the Lukashenko regime launched a campaign against the Polish ethnic minority.[111]

Poland is the sixth most populous member state of the European Union and, ever since joining in 2004, has pursued policies to increase its role in European affairs. Poland has a grand total of 51 representatives in the European Parliament. From 2009 to 2012, Jerzy Buzek, a former Prime Minister of Poland, was President of the European Parliament.[112]

Administrative divisions

Poland's current voivodeships (provinces) are largely based on the country's historic regions, whereas those of the past two decades (to 1998) had been centred on and named for individual cities. The new units range in area from less than 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) for Opole Voivodeship to more than 35,000 square kilometres (14,000 sq mi) for Masovian Voivodeship. Administrative authority at voivodeship level is shared between a government-appointed voivode (governor), an elected regional assembly (sejmik) and an executive elected by that assembly.

The voivodeships are subdivided into powiats (often referred to in English as counties), and these are further divided into gminas (also known as communes or municipalities). Major cities normally have the status of both gmina and powiat. Poland has 16 voivodeships, 379 powiats (including 65 cities with powiat status), and 2,478 gminas.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Military

.jpg)

The Polish armed forces are composed of four branches: Land Forces (Wojska Lądowe), Navy (Marynarka Wojenna), Air Force (Siły Powietrzne) and Special Forces (Wojska Specjalne). The military is subordinate to the Minister for National Defence. However, its sole commander-in-chief is the President of the Republic.

The Polish army consists of 65,000 active personnel, whilst the navy and air force respectively employ 14,300 and 26,126 servicemen and women. The Polish Navy is one of the larger navies on the Baltic Sea and is mostly involved in Baltic operations such as search and rescue provision for the section of the Baltic under Polish command, as well as hydrographic measurements and research; however, the Polish Navy played a more international role as part of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, providing logistical support for the United States Navy. The current position of the Polish Air Force is much the same; it has routinely taken part in Baltic Air Policing assignments, but otherwise, with the exception of a number of units serving in Afghanistan, has seen no active combat since the end of the Second World War. In 2003, the F-16C Block 52 was chosen as the new general multi-role fighter for the air force, the first deliveries taking place in November 2006; it is expected (2010) that the Polish Air Force will create three squadrons of F-16s, which will all be fully operational by 2012.

.jpg)

The most important mission of the armed forces is the defence of Polish territorial integrity and Polish interests abroad.[113] Poland's national security goal is to further integrate with NATO and European defence, economic, and political institutions through the modernisation and reorganisation of its military.[113] The armed forces is being re-organised according to NATO standards, and as of 1 January 2010, the transition to an entirely contract-based military has been completed. During the previous period, men were obliged to undertake compulsory military service. In the final stage of validity of this type of military service (since 2007 until the amendment of the law on conscription in 2008) the duration of compulsory service amounted nine months.[114]

Polish military doctrine reflects the same defensive nature as that of its NATO partners. From 1953 to 2009 Poland was a large contributor to various United Nations peacekeeping missions.[113][115] The Polish Armed Forces took part in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, deploying 2,500 soldiers in the south of that country and commanding the 17-nation Multinational force in Iraq.

The military was temporarily, but severely, affected by the loss of many of its top commanders in the wake the 2010 Polish Air Force Tu-154 crash near Smolensk, Russia, which killed all 96 passengers and crew, including, among others, the Chief of the Polish Army's General Staff Franciszek Gągor and Polish Air Force commanding general Andrzej Błasik. They were en route from Warsaw to attend an event to mark the 70th anniversary of the Katyn massacre, whose site is commemorated approximately 19 km (12 mi) west of Smolensk.[116][117]

Law enforcement and emergency services

Poland has a highly developed system of law enforcement with a long history of effective policing by the State Police Service. The structure of law enforcement agencies within Poland is a multi-tier one, with the State Police providing criminal-investigative services, Municipal Police serving to maintain public order and a number of other specialised agencies, such as the Polish Border Guard, acting to fulfil their assigned missions. In addition to these state services, private security companies are also common, although they possess no powers assigned to state agencies, such as, for example, the power to make an arrest or detain a suspect.

Emergency services in Poland consist of the emergency medical services, search and rescue units of the Polish Armed Forces and State Fire Service. Emergency medical services in Poland are, unlike other services, provided for by local and regional government.

Since joining the European Union all of Poland's emergency services have been undergoing major restructuring and have, in the process, acquired large amounts of new equipment and staff.[118] All emergency services personnel are now uniformed and can be easily recognised thanks to a number of innovative design features, such as reflective paint and printing, present throughout their service dress and vehicle liveries. In addition to this, in an effort to comply with EU standards and safety regulations, the police and other agencies have been steadily replacing and modernising their fleets of vehicles; this has left them with thousands of new automobiles, as well as many new aircraft, boats and helicopters.[119]

Economy

Poland's high-income economy[22] is considered to be one of the healthiest of the post-Communist countries and is one of the fastest growing within the EU.[120] Having a strong domestic market, low private debt, flexible currency, and not being dependent on a single export sector, Poland is the only European economy to have avoided the late-2000s recession.[121] Since the fall of the communist government, Poland has pursued a policy of liberalising the economy. It is an example of the transition from a centrally planned to a primarily market-based economy. In 2009 Poland had the highest GDP growth in the EU - 1.6%.[122][123][124] The country's most successful exports include machinery, furniture, foods and meats,[125] motor boats, light planes, hardwood products, casual clothing, shoes and cosmetics.[126] Germany is by far the biggest importer of Poland's exports as of 2013.[127]

The privatization of small and medium state-owned companies and a liberal law on establishing new firms have allowed the development of the private sector. As a consequence, consumer rights organizations have also appeared. Restructuring and privatisation of "sensitive sectors" such as coal, steel, rail transport and energy has been continuing since 1990. Between 2007 and 2010, the government plans to float twenty public companies on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, including parts of the coal industry. The biggest privatisations have been the sale of the national telecoms firm Telekomunikacja Polska to France Télécom in 2000, and an issue of 30% of the shares in Poland's largest bank, PKO Bank Polski, on the Polish stockmarket in 2004.

The Polish banking market is the largest in East Central and Eastern European region,[128] with 32.3 branches per 100,000 adults.[129][130] The banks are the largest and most developed sector of the country's financial markets. They are regulated by the Polish Financial Supervision Authority. During the transformation to a market-oriented economy, the government privatized some of them, recapitalized the rest, and introduced legal reforms that made the sector competitive. This has attracted a significant number of strategic foreign investors (ICFI). Poland's banking sector has approximately 5 national banks, a network of nearly 600 cooperative banks and 18 branches of foreign-owned banks. In addition, foreign investors have controlling stakes in nearly 40 commercial banks, which make up 68% of the banking capital.[128]

Poland has a large number of private farms in its agricultural sector, with the potential to become a leading producer of food in the European Union. The biggest money-makers abroad include smoked and fresh fish, fine chocolate, and dairy products, meats and specialty breads,[131] with the exchange rate conducive to export growth.[132] Food exports amounted to 62 billion zloty in 2011, increasing by 17% from 2010.[133] Structural reforms in health care, education, the pension system, and state administration have resulted in larger-than-expected fiscal pressures. Warsaw leads Central Europe in foreign investment. GDP growth had been strong and steady from 1993 to 2000 with only a short slowdown from 2001 to 2002.

The economy had growth of 3.7% annually in 2003, a rise from 1.4% annually in 2002. In 2004, GDP growth equaled 5.4%, in 2005 3.3% and in 2006 6.2%.[134] According to Eurostat data, Polish PPS GDP per capita stood at 67% of the EU average in 2012.[135]

In terms of the clarity, efficiency and neutrality of Poland's legal framework for multinational investors, a 2012 report by the World Economic Forum concluded that the ongoing foreign business disputes may "have damaged Poland's reputation as an attractive location for FDI" from other countries by creating the impression of "substandard reputation for maintaining an efficient and neutral framework to settle business disputes."[136] Ernst and Young's 2010 European attractiveness survey reported that Poland saw a 52% decrease in FDI foreign job creation and a 42% decrease in number of FDI projects since 2008.[137]

Average salaries in the enterprise sector in December 2010 were 3,848 PLN (1,012 euro or 1,374 US dollars)[138] and growing sharply.[139] Salaries vary between the regions: the median wage in the capital city Warsaw was 4,603 PLN (1,177 euro or 1,680 US dollars) while in Kielce it was 3,083 PLN (788 euro or 1125 US dollars). There is a wide distribution of salaries among the various districts of Poland. They range from 2,020 PLN (517 euro or 737 US dollars) in Kępno County, which is located in Greater Poland Voivodeship to 5,616 (1,436 euro or 2,050 US dollars) in Lubin County, which lies in Lower Silesian Voivodeship.[140]

.jpg)

According to a Credit Suisse report, Poles are the second wealthiest (after Czechs) of the Central European peoples.[141][142][143] Even though since World War II Poland is almost an ethnically homogeneous country, the number of foreign investors among immigrants is growing every year.[143][144]

Since the opening of the labor market in the European Union, Poland experienced a mass emigration of over 2.3 million abroad, mainly due to higher wages offered abroad, and due to the raise in levels of unemployment following the global Great Recession of 2008.[145][146][147] The out migration has increased the average wages for the workers who remained in Poland, in particular for those with intermediate level skills.[148]

Commodities produced in Poland include: electronics, cars (Arrinera, Leopard), buses (Solaris, Solbus), helicopters (PZL Świdnik), transport equipment, locomotives, planes (PZL Mielec), ships, military engineering (including tanks, SPAAG systems), medicines (Polpharma, Polfa), food, clothes, glass, pottery (Bolesławiec), chemical products and others.

Corporations

Poland is recognised as a regional economic power within East-Central Europe, with nearly 40 percent of the 500 biggest companies in the region (by revenues) as well as a high globalisation rate.[149] Poland was the only member of the EU to avoid the recession of the late 2000s, a testament to the Polish economy's stability. The country's most competitive firms are components of the WIG30 which is traded on the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

Well known Polish brands include, among others, PKO BP, PKN Orlen, PGE, PZU, PGNiG, Tauron Group, Lotos Group, KGHM Polska Miedź, Asseco, Plus, Play, PLL LOT, Poczta Polska, PKP, Biedronka, and TVP.[150]

Poland is recognised as having an economy with development potential, overtaking the Netherlands in mid-2010 to become Europe's sixth largest economy.[151] Foreign Direct Investment in Poland has remained steady ever since the country's re-democratisation following the Round Table Agreement in 1989. However, problems still exist. It is believed that progress of privatization was uneven across sectors due to emergence of interest groups supporting government's push for the reforms based on feasibility rather than efficiency, at the cost of Poland's remaining sectors in need of development and modernisation, such as the extractive industries.[152]

The list includes the largest companies by turnover in 2011, but does not include major banks or insurance companies:

| Rank 2011 [153] | Corporation | Sector | Headquarters | Revenue (Thou. PLN) | Profit (Thou. PLN) | Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | PKN Orlen SA | oil and gas | Płock | 79 037 121 | 2 396 447 | 4,445 |

| 2. | Lotos Group SA | oil and gas | Gdańsk | 29 258 539 | 584 878 | 5,168 |

| 3. | PGE SA | energy | Warsaw | 28 111 354 | 6 165 394 | 44,317 |

| 4. | Jerónimo Martins | retail | Kostrzyn | 25 285 407 | N/A | 36,419 |

| 5. | PGNiG SA | oil and gas | Warsaw | 23 003 534 | 1 711 787 | 33,071 |

| 6. | Tauron Group SA | energy | Katowice | 20 755 222 | 1 565 936 | 26,710 |

| 7. | KGHM Polska Miedź SA | mining | Lubin | 20 097 392 | 13 653 597 | 18,578 |

| 8. | Metro Group Poland | retail | Warsaw | 17 200 000 | N/A | 22,556 |

| 9. | Fiat Auto Poland SA | automotive | Bielsko-Biała | 16 513 651 | 83 919 | 5,303 |

| 10. | Orange Polska | telecommunications | Warsaw | 14 922 000 | 1 785 000 | 23,805 |

Tourism

Poland experienced an increase in the number of tourists after joining the European Union.[154] Tourism contributes significantly to Poland's overall economy and makes up a relatively large proportion of the country's service market.[155]