Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |

Westergren pipet array on StaRRsed automated ESR analyzer |

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), also called a sedimentation rate or Westergren ESR, is the rate at which red blood cells sediment in a period of one hour. It is a common hematology test, and is a non-specific measure of inflammation. To perform the test, anticoagulated blood was traditionally placed in an upright tube, known as a Westergren tube, and the rate at which the red blood cells fall was measured and reported in mm/h.

Since the introduction of automated analyzers into the clinical laboratory, the ESR test has been automatically performed.

The ESR is governed by the balance between pro-sedimentation factors, mainly fibrinogen, and those factors resisting sedimentation, namely the negative charge of the erythrocytes (zeta potential). When an inflammatory process is present, the high proportion of fibrinogen in the blood causes red blood cells to stick to each other. The red cells form stacks called 'rouleaux,' which settle faster, due to their increased density. Rouleaux formation can also occur in association with some lymphoproliferative disorders in which one or more immunoglobulins are secreted in high amounts. Rouleaux formation can, however, be a normal physiological finding in horses, cats, and pigs.

The ESR is increased in inflammation, pregnancy, anemia, autoimmune disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus), infections, some kidney diseases and some cancers (such as lymphoma and multiple myeloma). The ESR is decreased in polycythemia, hyperviscosity, sickle cell anemia, leukemia, low plasma protein (due to liver or kidney disease) and congestive heart failure. The basal ESR is slightly higher in females.[1]

Medical uses

Diagnosis

It can sometimes be useful in diagnosing some diseases, such as multiple myeloma, temporal arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, various auto-immune diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease[2] and chronic kidney diseases. In many of these cases, the ESR may exceed 100 mm/hour.[3]

It is commonly used for a differential diagnosis for Kawasaki's disease (from Takayasu's arteritis; which would have a markedly elevated ESR) and it may be increased in some chronic infective conditions like tuberculosis and infective endocarditis. It is also elevated in subacute thyroiditis also known as DeQuervain's.

Stages in erythrocyte sedimentation:

There are 3 stages in erythrocyte sedimentation

1) Stage 1 : Rouleaux formation - First 10 minutes

2) Stage 2 : Sedimentation or settling stage - 40 mins

3) Stage 3 : Packing stage - 10 minutes (sedimentation slows and cells start to pack at the bottom of the tube)

Disease severity

It is a component of the PCDAI (Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index), an index for assessment of severity of inflammatory bowel disease in children.

Monitoring response to therapy

The clinical usefulness of ESR is limited to monitoring the response to therapy in certain inflammatory diseases such as temporal arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica and rheumatoid arthritis. It can also be used as a crude measure of response in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Additionally, ESR levels are used to define one of the several possible adverse prognostic factors in the staging of Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Normal values

Note: mm/h. = millimeters per hour.

Westergren's original normal values (men 3 mm and women 7 mm)[4] made no allowance for a person's age. In 1967 it was confirmed that ESR values tend to rise with age and to be generally higher in women.[5] Values are increased in states of anemia,[6] and in black populations.[7]

Adults

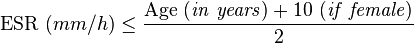

The widely used[8] rule calculating normal maximum ESR values in adults (98% confidence limit) is given by a formula devised in 1983:[9]

This formula is no longer credited. Other studies show only a small dependence of ESR on age and much lower values, as seen in the following:

ESR reference ranges from a large 1996 study of 3,910 healthy adults:[10]

| Age | 20 | 55 | 90 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men—5% exceed | 12 | 14 | 19 |

| Women—5% exceed | 18 | 21 | 23 |

Children

Normal values of ESR have been quoted as 1[11] to 2[12] mm/h at birth, rising to 4 mm/h 8 days after delivery,[12] and then to 17 mm/h by day 14.[11]

Typical normal ranges quoted are:[13]

- Newborn: 0 to 2 mm/h

- Neonatal to puberty: 3 to 13 mm/h, but other laboratories place an upper limit of 20.[14]

Relation to C-reactive protein

C-reactive protein is an acute phase protein produced by the liver during an inflammatory reaction. Since C-reactive protein levels in the blood rise more quickly after the inflammatory or infective process begins, ESR is often replaced with C-reactive protein measurement. There are specific drawbacks, however: for example, both tests for ESR and CRP were found to be independently associated with a diagnosis of acute maxillary sinusitis[15] so in some cases the combination of the two measurements may improve diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Several studies investigated the differential diagnostic values of ESR and CRP in inflammatory disease, and concluded ESR is a potential meaningful biomarker for disease differentiation.[2]

History

The test was invented in 1897 by the Polish pathologist Edmund Biernacki.[16][17] In some parts of the world the test continues to be referred to as Biernacki's Reaction (Polish: odczyn Biernackiego, OB). In 1918 the Swedish pathologist Robert Sanno Fåhræus declared the same and, along with Alf Vilhelm Albertsson Westergren, are eponymously remembered for the Fåhræus-Westergren test (abbreviated as FW test; in the UK, usually termed Westergren test),[18] which uses sodium citrate-anti-coagulated specimens.[19]

References

- ↑ "ESR". MedlinePlus: U.S. National Library of Medicine & National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- 1 2 Liu, S; Ren, J; Xia, Q; Wu, X; Han, G; Ren, H; Yan, D; Wang, G; Gu, G; Li, J (May 17, 2013). "Preliminary Case-control Study to Evaluate Diagnostic Values of C-Reactive Protein and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate in Differentiating Active Crohn's Disease From Intestinal Lymphoma, Intestinal Tuberculosis and Behcet's Syndrome.". The American journal of the medical sciences 346 (6): 467–72. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182959a18. PMID 23689052.

- ↑ "Sedimentation Rate". WebMD. 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ↑ Westergren A (1957). "Diagnostic tests: the erythrocyte sedimentation rate range and limitations of the technique". Triangle 3 (1): 20–5. PMID 13455726.

- ↑ Böttiger LE, Svedberg CA (1967). "Normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and age". Br Med J 2 (5544): 85–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5544.85. PMC 1841240. PMID 6020854.

- ↑ Kanfer EJ, Nicol BA (1997). "Haemoglobin concentration and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in primary care patients" (Scanned & PDF). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 90 (1): 16–8. PMC 1296109. PMID 9059375.

- ↑ Gillum RF (1993). "A racial difference in erythrocyte sedimentation". Journal of the National Medical Association 85 (1): 47–50. PMC 2571720. PMID 8426384.

- ↑ Reference range (ESR) at GPnotebook

- ↑ Miller A, Green M, Robinson D (1983). "Simple rule for calculating normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 286 (6361): 266. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6361.266. PMC 1546487. PMID 6402065.

- ↑ Wetteland P, Røger M, Solberg HE, Iversen OH (1996). "Population-based erythrocyte sedimentation rates in 3910 subjectively healthy Norwegian adults. A statistical study based on men and women from the Oslo area". J. Intern. Med. 240 (3): 125–31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.30295851000.x. PMID 8862121. - listing upper reference levels expected to be exceeded only by chance in 5% of subjects

- 1 2 Adler SM, Denton RL (1975). "The erythrocyte sedimentation rate in the newborn period". J. Pediatr. 86 (6): 942–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(75)80233-2. PMID 1168702.

- 1 2 Ibsen KK, Nielsen M, Prag J, et al. (1980). "The value of the micromethod erythrocyte sedimentation rate in the diagnosis of infections in newborns". Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. Suppl 23: 143–5. PMID 6937959.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia ESR

- ↑ Mack DR, Langton C, Markowitz J, LeLeiko N, Griffiths A, Bousvaros A, Evans J, Kugathasan S, Otley A, Pfefferkorn M, Rosh J, Mezoff A, Moyer S, Oliva-Hemker M, Rothbaum R, Wyllie R, delRosario JF, Keljo D, Lerer T, Hyams J (1 June 2007). "Laboratory Values for Children With Newly Diagnosed Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Pediatrics 119 (6): 1113–1119. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1865. PMID 17545378. - as commented on at

* Bauchner H (2007-06-13). "Lab Screening in Children with Suspected Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal Watch Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. Retrieved 2008-03-01. - ↑ Jens Georg Hansen, Henrik Schmidt, Jorn Rosborg, Elisabeth Lund (22 July 1995). "Predicting acute maxillary sinusitis in a general practice population". BMJ 311 (6999): 233–236. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.6999.233. PMC 2550286. PMID 7627042.

- ↑ Iłowiecki, Maciej (1981). Dzieje nauki polskiej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo „Interpress”. p. 195. ISBN 83-223-1876-6.

- ↑ Edmund Faustyn Biernacki and eponymously named Biernacki's test at Who Named It?

- ↑ Robert (Robin) Sanno Fåhræus and Alf Vilhelm Albertsson Westergren who are eponymously named for the Fåhræus-Westergren test (aka Westergren test) at Who Named It?

- ↑ International Council for Standardization in Haematology (Expert Panel on Blood Rheology) (1993). "ICSH recommendations for measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate. International Council for Standardization in Haematology (Expert Panel on Blood Rheology)". J. Clin. Pathol. 46 (3): 198–203. doi:10.1136/jcp.46.3.198. PMC 501169. PMID 8463411.

External links

- Mediscuss on ESR

- American Family Physician article on ESR

- ESR at Lab Tests Online

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||