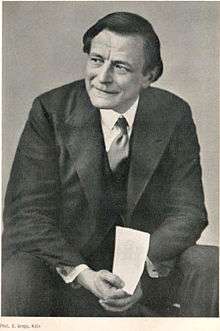

Ernst Barthel

Ernst Philipp Barthel (17 October 1890 in Schiltigheim – 16 February 1953 in Oberkirch (Baden) was an Alsatian philosopher, mathematician and inventor.[1] In the 1920s and 1930s he taught as a private lecturer of philosophy at the University of Cologne. From 1924 on Barthel edited the magazine Antäus. Blätter für neues Wirklichkeitsdenken (Antaeus. Journal for new Reality Thinking), which served as the organ of the Gesellschaft für Lebensphilosophie (Society for Life Philosophy) founded by him in Cologne. Barthel maintained philosophical friendships with his compatriots Albert Schweitzer and Friedrich Lienhard.

Philosophy and Earth theory

The main principle of Barthel's philosophy on the background of Christian Platonism was the Polarity, which he understood to be the most fundamental, constitutive law in all of nature.

Besides his philosophical work he also published several works on geometry, further developing a non-Euclidean (Riemannian geometry, spherical) theory of geometry, which he called polar geometry. From this geometry he derived a new cosmology with the theory of a Great Earth, which states that the Earth is a maximal sphere in a cyclical space and its surface therefore a total plane, the equator plane of the Cosmos. The (total) plane, as well as the straight line and space as a whole, is flat, without curvature yet closed, running back on itself. Barthel considered this his most important theory, even the most significant thought of the century, as he writes in his autobiography.[2] While some of his academic colleagues stated that this theory is geometrically possible and consistent, others did not acknowledge that and resorted to "the blight of personal calumny",[3] deriding him for allegedly "teaching that the Earth is a disk" or outright declaring him crazy, thus ruining his academic career.[4] In November 1940 he was dismissed from the University of Cologne by the Nazi Reich Minister Rust because of religio-metaphysical (due to his book Der Mensch und die ewigen Hintergründe) and political (alleged Francophilia) suspicions. Ernst Barthel was a member of the National Socialist Teachers League.[5]

The Russian astronomer Leonid Andrenko considered Barthel's main thought among the most ingenious ever suggested and advocated for taking note of it and thinking about it.[6]

Works

- Elemente der transzendentalen Logik, Dissertation, Straßburg, 1913

- Die Erde als Totalebene. Hyperbolische Raumtheorie mit einer Voruntersuchung über die Kegelschnitte (The Earth as total plane), 1914

- Vertikaldimension und Weltraum. Neue Beweise gegen die Kugelgestalt der Erde, 1914

- Der Irrtum «g». Ein Traktat über den freien Fall, 1914

- Harmonische Astronomie (Harmonical astronomy), 1916

- Polargeometrie, 1919

- Goethes Wissenschaftslehre in ihrer modernen Tragweite, 1922

- Goethes Relativitätstheorie der Farbe. Nebst einer musikästhetischen Parallele, 1923

- Lebensphilosophie, 1923

- Philosophie des Eros, 1926

- Deutschlands und Europas Schicksalsfrage, in: Zeitschrift für Geopolitik 3 (1926), pp. 303–309.

- Form und Seele. Dichtungen, 1927

- Die Welt als Spannung und Rhythmus, 1928

- Albert Schweitzer as Theologian, in: The Hibbert Journal, XXVI, 4 (1928)

- Elsässische Geistesschicksale. Ein Beitrag zur europäischen Verständigung, 1928

- Erweiterung raumtheoretischer Denkmöglichkeiten durch die Riemannsche Geometrie, in: Astronomische Nachrichten, Vol. 236 (1929), pp. 139–148.

- Goethe, das Sinnbild deutscher Kultur, 1930

- Die Monadologie der beiden Welten. Abriß der Metaphysik, Jahrbuch der Elsaß-Lothringischen Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft zu Straßburg, Band III, SS. 147–185, 1930

- Kosmologische Briefe. Eine neue Lehre vom Weltall (Cosmological letters. A new teaching of the universe), 1931

- Vorstellung und Denken. Eine Kritik des pragmatischen Verstandes, 1931

- Einführung in die Polargeometrie, (Introduction to Polar Geometry) 2nd ed., 1932

- Beiträge zur transzendentalen Logik auf polaristischer Grundlage, 1932

- Geometrie und Kosmos, 1939

- Die Kosmologie der Großerde im Totalraum, Leipzig: Hillmann 1939

- Der Mensch und die ewigen Hintergründe (Man and the eternal background), 1939

- Die Erde als Grundkörper der Welt. Ebertin, Erfurt 1940. According to Barthel's autobiography, p. 231, this book was pulped by the Gestapo in 1941.

- Friedrich Lienhard. Die Künstlerseele aus dem deutschen Elsaß, Kolmar im Elsaß, Alsatia Verlag, 1941.

- Nietzsche als Verführer (Nietzsche as Seducer), 1947

- Mein Opfergang durch diese Zeit. Ein Leben im Kampf um Wahrheit und ein elsässisches Geistesschicksal (My self-sacrifice in these times. A life dedicated to the fight for truth and the fate of an Alsatian mind), Georg Duve (Hrsg.), 2005

Further reading

- Wurtz, Jean-Paul: Ernst Barthel: philosophe alsacien (1890–1953). Recueil d'études publié à l'occasion du centenaire de sa naissance. Strasbourg: Presses Univ. 1991.

- Criqui, Fernand: Ein tragisches Elsaesserschicksal: Ernest Barthel. (The tragic fate of an Alsatian: Ernest Barthel), in: Der grosse Straßburger Hinkende Bote, pp. 110–112, 1954

References

- ↑ cf. VDI-Nachrichten, 19. April 1933, for Barthel's Transformationszirkel (transformation dividers)

- ↑ Mein Opfergang durch diese Zeit, 2005, p. 119.

- ↑ Criqui, Fernand: Ein tragisches Elsaesserschicksal: Ernest Barthel, 1954

- ↑ Mein Opfergang durch diese Zeit, 2005, passim

- ↑ Ideologische Mächte im deutschen Faschismus Band 5: Heidegger im Kontext: Gesamtüberblick zum NS-Engagement der Universitätsphilosophen, George Leaman, Rainer Alisch, Thomas Laugstien, Publisher: Argument Hamburg, 1993, ISBN 3886192059

- ↑ E. Barthel, Mein Opfergang durch diese Zeit, 2005, p. 184.

External links

- Works by or about Ernst Barthel in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

|