Erdős–Ko–Rado theorem

In combinatorics, the Erdős–Ko–Rado theorem of Paul Erdős, Chao Ko, and Richard Rado is a theorem on intersecting set families. It is part of the theory of hypergraphs, specifically, uniform hypergraphs of rank r.

The theorem is as follows. Suppose that A is a family of distinct subsets of  such that each subset is of size r and each pair of subsets has a nonempty intersection, and suppose that n ≥ 2r. Then the number of sets in A is less than or equal to the binomial coefficient

such that each subset is of size r and each pair of subsets has a nonempty intersection, and suppose that n ≥ 2r. Then the number of sets in A is less than or equal to the binomial coefficient

A family of sets may also be called a hypergraph, and when all the sets are the same size it is called a uniform hypergraph. Since every set in A has size r,  is an r-uniform hypergraph.

is an r-uniform hypergraph.

According to Erdős (1987) the theorem was proved in 1938, but was not published until 1961 in an apparently more general form. The subsets in question were only required to be size at most r, and with the additional requirement that no subset be contained in any other. This statement is not actually more general: any subset that has size less than r can be increased to size exactly r to make the above statement apply.

Proof

The original proof of 1961 used induction on n. In 1972, Gyula O. H. Katona gave the following short proof using double counting.

Suppose we have some such family of subsets A. Arrange the elements of {1, 2, ..., n} in any cyclic order, and consider the sets from A that form intervals of length r within this cyclic order. For example if n = 8 and r = 3, we could arrange the numbers {1, 2, ..., 8} into the cyclic order (3,1,5,4,2,7,6,8), which has eight intervals:

- (3,1,5), (1,5,4), (5,4,2), (4,2,7), (2,7,6), (7,6,8), (6,8,3), and (8,3,1).

However, it is not possible for all of the intervals of the cyclic order to belong to A, because some pairs of them are disjoint. Katona's key observation is that at most r of the intervals for a single cyclic order may belong to A. To see this, note that if (a1, a2, ..., ar) is one of these intervals in A, then every other interval of the same cyclic order that belongs to A separates ai and ai + 1 for some i (that is, it contains precisely one of these two elements). The two intervals that separate these elements are disjoint, so at most one of them can belong to A. Thus, the number of intervals in A is one plus the number of separated pairs, which is at most (r-1).

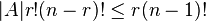

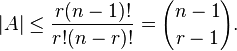

Based on this idea, we may count the number of pairs (S,C), where S is a set in A and C is a cyclic order for which S is an interval, in two ways. First, for each set S one may generate C by choosing one of r! permutations of S and (n − r)! permutations of the remaining elements, showing that the number of pairs is |A|r!(n − r)!. And second, there are (n − 1)! cyclic orders, each of which has at most r intervals of A, so the number of pairs is at most r(n − 1)!. Combining these two counts gives the inequality

and dividing both sides by r!(n − r)! gives the result

Families of maximum size

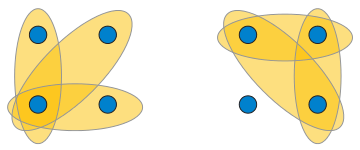

There are two different and straightforward constructions for an intersecting family of r-element sets achieving the Erdős–Ko–Rado bound on cardinality.

First, choose any fixed element x, and let A consist of all r-subsets of  that include x. For instance, if n = 4, r = 2, and x = 1, this produces the family of three 2-sets

that include x. For instance, if n = 4, r = 2, and x = 1, this produces the family of three 2-sets

- {1,2}, {1,3}, {1,4}.

Any two sets in this family intersect, because they both include x.

Second, when n = 2r and with x as above, let A consist of all r-subsets of  that do not include x.

For the same parameters as above, this produces the family

that do not include x.

For the same parameters as above, this produces the family

- {2,3}, {2,4}, {3,4}.

Any two sets in this family have a total of 2r = n elements among them, chosen from the n − 1 elements that are unequal to x, so by the pigeonhole principle they must have an element in common.

When n > 2r, families of the first type (variously known as sunflowers, stars, dictatorships, centred families, principal families) are the unique maximum families. Friedgut (2008) proved that in this case, a family which is almost of maximum size has an element which is common to almost all of its sets. This property is known as stability.

Maximal intersecting families

An intersecting family of r-element sets may be maximal, in that no further set can be added without destroying the intersection property, but not of maximum size. An example with n = 7 and r = 3 is the set of 7 lines of the Fano plane, much less than the Erdős–Ko–Rado bound of 15.

References

- Erdős, P. (1987), "My joint work with Richard Rado", in Whitehead, C., Surveys in combinatorics, 1987: Invited Papers for the Eleventh British Combinatorial Conference (PDF), London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series 123, Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–80, ISBN 978-0-521-34805-8.

- Erdős, P.; Ko, C.; Rado, R. (1961), "Intersection theorems for systems of finite sets" (PDF), Quarterly Journal of Mathematics. Oxford. Second Series 12: 313–320, doi:10.1093/qmath/12.1.313.

- Friedgut, Ehud (2008), "On the measure of intersecting families, uniqueness and stability" (PDF), Combinatorica 28 (5): 503–528, doi:10.1007/s00493-008-2318-9

- Katona, G. O. H. (1972), "A simple proof of the Erdös-Chao Ko-Rado theorem", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 13 (2): 183–184, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(72)90054-8.