Indeterminate form

In calculus and other branches of mathematical analysis, limits involving an algebraic combination of functions in an independent variable may often be evaluated by replacing these functions by their limits; if the expression obtained after this substitution does not give enough information to determine the original limit, it is said to take on an indeterminate form. The term was originally introduced by Cauchy's student Moigno in the middle of the 19th century.

The indeterminate forms typically considered in the literature are denoted 0/0, ∞/∞, 0 × ∞, ∞ − ∞, 00, 1∞ and ∞0.

Discussion

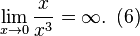

The most common example of an indeterminate form occurs as the ratio of two functions, in which both of these functions tend to zero in the limit, and is referred to as "the indeterminate form 0/0". As x approaches 0, the ratios x/x3, x/x, and x2/x go to ∞, 1, and 0 respectively. In each case, if the limits of the numerator and denominator are substituted, the resulting expression is 0/0, which is undefined. So, in a manner of speaking, 0/0 can take on the values 0, 1 or ∞, and it is possible to construct similar examples for which the limit is any particular value.

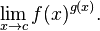

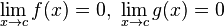

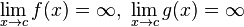

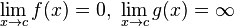

More formally, the fact that the functions f(x) and g(x) both approach 0 as x approaches some limit point c is not enough information to evaluate the limit

Not every undefined algebraic expression corresponds to an indeterminate form. For example, the expression 1/0 is undefined as a real number but does not correspond to an indeterminate form, because any limit that gives rise to this form will diverge to infinity.

An indeterminate form expression may have a value in some contexts. For example, if κ is an infinite cardinal number then expressions 0κ, 00, 1κ and κ0 are well-defined in the context of cardinal arithmetic. See also § Zero to the power of zero. Note that zero to the power infinity is not an indeterminate form.

Some examples and non-examples

Indeterminate form 0/0

-

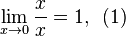

(1)

-

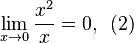

(2)

-

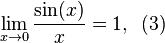

(3)

-

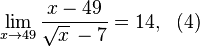

(4)

-

(5)

-

(6)

The indeterminate form 0/0 is particularly common in calculus because it often arises in the evaluation of derivatives using their limit definition.

As mentioned above,

while

This is enough to show that 0/0 is an indeterminate form. Other examples with this indeterminate form include

and

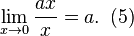

Direct substitution of the number that x approaches into any of these expressions shows that these are examples of the indeterminate form 0/0, but these limits take many different values. Any desired value a can be obtained for this indeterminate form as follows:

The value infinity can also be obtained (in the sense of divergence to infinity):

Indeterminate form 00

-

(7)

-

(8)

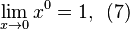

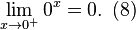

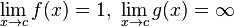

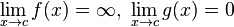

The following limits illustrate that the expression 00 is an indeterminate form:

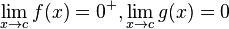

Thus, in general, knowing that  and

and  is not sufficient to calculate the limit

is not sufficient to calculate the limit

If the functions f and g are analytic at c, and f is positive for x sufficiently close (but not equal) to c, then the limit of f(x) g(x) will be 1.[1] Otherwise, use the transformation in the table below to evaluate the limit.

Expressions that are not indeterminate forms

The expression 1/0 is not commonly regarded as an indeterminate form because there is not an infinite range of values that f/g could approach. Specifically, if f approaches 1 and g approaches 0, then f and g may be chosen so that (1) f/g approaches +∞, (2) f/g approaches −∞, or (3) the limit fails to exist. In each case the absolute value |f/g| approaches +∞, and so the quotient f/g must diverge, in the sense of the extended real numbers. (In the framework of the real projective line, the limit is the unsigned infinity ∞ in all three cases.) Similarly, any expression of the form a/0, with a ≠ 0 (including a = +∞ and a = −∞), is not an indeterminate form since a quotient giving rise to such an expression will always diverge.

The expression 0∞ is not an indeterminate form. The expression 0+∞ has the limiting value 0 for the given individual limits, and the expression 0−∞ is equivalent to 1/0.

Evaluating indeterminate forms

The adjective indeterminate does not imply that the limit does not exist, as many of the examples above show. In many cases, algebraic elimination, L'Hôpital's rule, or other methods can be used to manipulate the expression so that the limit can be evaluated.

For example, the expression x2/x can be simplified to x at any point other than x = 0. Thus, the limit of this expression as x approaches 0 (which depends only on points near 0, not at x = 0 itself) is the limit of x, which is 0. Most of the other examples above can also be evaluated using algebraic simplification.

Equivalent infinitesimal

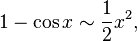

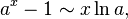

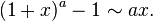

When two variables  and

and  converge to zero at the same point and

converge to zero at the same point and  , they are called equivalent infinitesimal.

, they are called equivalent infinitesimal.

For the evaluation of the indeterminate form 0/0, we can use the following equivalent infinitesimals:

For example:

![\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x^{3}}}[({\frac {2+\cos x}{3}})^{x}-1]=\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {e^{x\ln {\frac {2+\cos x}{3}}}-1}{x^{3}}}=\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x^{2}}}\ln {\frac {2+\cos x}{3}}=\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x^{2}}}\ln({\frac {\cos x-1}{3}}+1)=\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {\cos x-1}{3x^{2}}}=-{\frac {1}{6}}](../I/m/61c31bc22a5fea2bc15930d4149e6bf9.png)

Here is a brief proof:

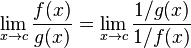

Suppose there are two equivalent infinitesimals  and

and  .

.

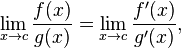

L'Hôpital's rule

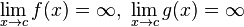

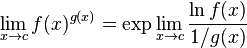

L'Hôpital's rule is a general method for evaluating the indeterminate forms 0/0 and ∞/∞. This rule states that (under appropriate conditions)

where f' and g' are the derivatives of f and g. (Note that this rule does not apply to expressions ∞/0, 1/0, and so on; these expressions are not indeterminate forms.) These derivatives will allow one to perform algebraic simplification and eventually evaluate the limit.

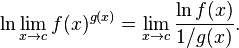

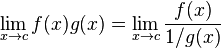

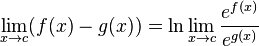

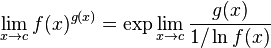

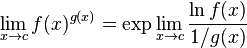

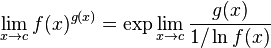

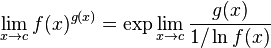

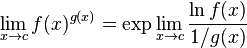

L'Hôpital's rule can also be applied to other indeterminate forms, using first an appropriate algebraic transformation. For example, to evaluate the form 00:

The right-hand side is of the form ∞/∞, so L'Hôpital's rule applies to it. Note that this equation is valid (as long as the right-hand side is defined) because the natural logarithm (ln) is a continuous function; it is irrelevant how well-behaved f and g may (or may not) be as long as f is asymptotically positive.

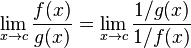

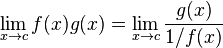

Although L'Hôpital's rule applies both to 0/0 and to ∞/∞, one of these forms may be more useful than the other in a particular case (because of the possibility of algebraic simplification afterwards). One can change between these forms, if necessary, by transforming f/g to (1/g)/(1/f).

List of indeterminate forms

The following table lists the most common indeterminate forms and the transformations for applying l'Hôpital's rule.

| Indeterminate form | Conditions | Transformation to 0/0 | Transformation to ∞/∞ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0/0 |  |

| |

| ∞/∞ |  |

|

|

| 0 × ∞ |  |

|

|

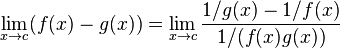

| ∞ − ∞ |  |

|

|

| 00 |  |

|

|

| 1∞ |  |

|

|

| ∞0 |  |

|

|

See also

References

- ↑ Louis M. Rotando; Henry Korn (January 1977). "The indeterminate form 00". Mathematics Magazine 50 (1): 41–42. doi:10.2307/2689754.