Ephedrine

-Ephedrin.svg.png) | |

-Ephedrine_molecule_from_xtal_ball.png) | |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

|

(R*,S*)-2-(methylamino)-1-phenylpropan-1-ol | |

| Clinical data | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Trade names | Bronkaid, Primatene |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Legal status |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth, IV, IM, SC |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 85% |

| Metabolism | minimal liver |

| Onset of action | IV (seconds), IM (10 to 20min), by mouth (15 to 60min)[1] |

| Biological half-life | 3–6 hours |

| Duration of action | IV/IM (60min), by mouth (2 to 4 hours) |

| Excretion | 22-99% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

299-42-3 |

| ATC code | C01CA26 R01AA03, R01AB05 (combinations), R03CA02, S01FB02, QG04BX90 |

| PubChem | CID 5032 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 556 |

| DrugBank |

DB01364 |

| ChemSpider |

8935 |

| UNII |

7CUC9DDI9F |

| KEGG |

D00124 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:15407 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL211456 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C10H15NO |

| Molar mass | 165.23 |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ephedrine is a medication used to prevent low blood pressure during spinal anesthesia.[1] It has also been used for asthma, narcolepsy, and obesity but is not the preferred treatment. It can be taken by mouth or by injection into a muscle, vein, or just under the skin. Onset with intravenous use is fast, while injection into a muscle can take 20 minutes, and by mouth can take an hour for effect. When given by injection it lasts about an hour and when taken by mouth it can last up to four hours.[1]

Common side effects include, trouble sleeping, anxiety, headache, hallucinations, high blood pressure, fast heart rate, loss of appetite, and inability to urinate. Serious side effects include stroke, heart attack, and abuse.[1] While likely okay in pregnancy its use in this population is poorly studied.[2][3] Use during breastfeeding is not recommended.[3] Ephedrine works by turning on alpha adrenergic receptors and beta adrenergic receptors.[1]

Ephedrine was first isolated in 1885.[4] It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[5] It is available as a generic medication.[1] The wholesale cost is about 0.69 to 1.35 USD per dose.[6] In the United States it is not very expensive.[7] It can normally be found in plants of the Ephedra type. Dietary supplements that contain ephedrine are illegal in the United States. An exception is when used in traditional Chinese medicine.[1]

Medical use

Both ephedrine and pseudoephedrine increase blood pressure and act as bronchodilators, with pseudoephedrine having considerably less effect. [8]

Weight loss

Ephedrine promotes modest short-term weight loss,[9] specifically fat loss, but its long-term effects are unknown.[10] In mice ephedrine is known to stimulate thermogenesis in the brown adipose tissue, but because adult humans have only small amounts of brown fat, thermogenesis is assumed to take place mostly in the skeletal muscle. Ephedrine also decreases gastric emptying. Methylxanthines such as caffeine and theophylline have a synergistic effect with ephedrine with respect to weight loss. This led to creation and marketing of compound products.[11] One of them, known as the ECA stack, contains caffeine and aspirin besides ephedrine, and is a popular supplement taken by body builders to cut down body fat before a competition. It increases performance in athletes, and has a synergistic effect with caffeine.[12]

Recreational use

As a phenethylamine, ephedrine has a similar chemical structure to amphetamines and is a methamphetamine analogue having the methamphetamine structure with a hydroxyl group at the β position. Because of ephedrine's structural similarity to methamphetamine, it can be used to create methamphetamine using chemical reduction in which ephedrine's hydroxyl group is removed; this has made ephedrine a highly sought-after chemical precursor in the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine. The most popular method for reducing ephedrine to methamphetamine is similar to the Birch reduction, in that it uses anhydrous ammonia and lithium metal in the reaction. The second-most popular method uses red phosphorus, iodine, and ephedrine in the reaction.

Through oxidation, ephedrine can be easily synthesized into methcathinone. Ephedrine is listed as a table-I precursor under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.[13]

Detection of use

Ephedrine may be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to monitor possible abuse by athletes, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Many commercial immunoassay screening tests directed at the amphetamines cross-react appreciably with ephedrine, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish ephedrine from other phenethylamine derivatives. Blood or plasma ephedrine concentrations are typically in the 20-200 µg/l range in persons taking the drug therapeutically, 300-3000 µg/l in abusers or poisoned patients and 3–20 mg/l in cases of acute fatal overdosage. The current WADA limit for ephedrine in an athlete's urine is 10 µg/ml.[14][15][16][17]

Contraindications

Ephedrine should not be used in conjunction with certain antidepressants, namely norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), as this increases the risk of symptoms due to excessive serum levels of norepinephrine.

Bupropion is an example of an antidepressant with an amphetamine-like structure similar to ephedrine, and it is an NDRI. Its action bears more resemblance to amphetamine than to fluoxetine in that its primary mode of therapeutic action involves norepinephrine and to a lesser degree dopamine, but it also releases some serotonin from presynaptic clefts. It should not be used with ephedrine, as it may increase the likelihood of side effects.

Ephedrine should be used with caution in patients with inadequate fluid replacement, impaired adrenal function, hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, prostatic hypertrophy, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, during delivery if maternal blood pressure is >130/80 mmHg, and lactation.[18]

Contraindications for the use of ephedrine include: closed-angle glaucoma, phaeochromocytoma, asymmetric septal hypertrophy (idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis), concomitant or recent (previous 14 days) monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy, general anaesthesia with halogenated hydrocarbons (particularly halothane), tachyarrhythmias or ventricular fibrillation, or hypersensitivity to ephedrine or other stimulants.

Ephedrine should not be used at any time during pregnancy unless specifically indicated by a qualified physician and only when other options are unavailable.[18]

Adverse effects

Ephedrine is a potentially dangerous natural compound; as of 2004 the US Food and Drug Administration had received over 18,000 reports of adverse effects in people using it.[19]

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are more common with systemic administration (e.g. injection or oral administration) compared to topical administration (e.g. nasal instillations). ADRs associated with ephedrine therapy include:[20]

- Cardiovascular: tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, angina pectoris, vasoconstriction with hypertension

- Dermatological: flushing, sweating, acne vulgaris

- Gastrointestinal: nausea

- Genitourinary: decreased urination due to vasoconstriction of renal arteries, difficulty urinating is not uncommon, as alpha-agonists such as ephedrine constrict the internal urethral sphincter, mimicking the effects of sympathetic nervous system stimulation

- Nervous system: restlessness, confusion, insomnia, mild euphoria, mania/hallucinations (rare except in previously existing psychiatric conditions), delusions, formication (may be possible, but lacks documented evidence) paranoia, hostility, panic, agitation

- Respiratory: dyspnea, pulmonary edema

- Miscellaneous: dizziness, headache, tremor, hyperglycemic reactions, dry mouth

The neurotoxicity of l-ephedrine is disputed. [21]

Other uses

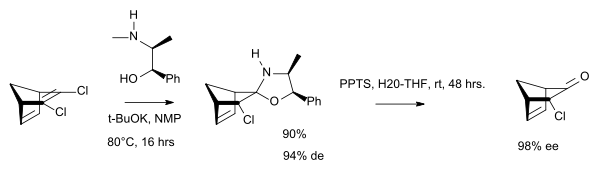

In chemical synthesis, ephedrine is used in bulk quantities as a chiral auxiliary group. [22]

In saquinavir synthesis, the half-acid is resolved as its salt with l-ephedrine.

Chemistry and nomenclature

Ephedrine is a sympathomimetic amine and substituted amphetamine. It is similar in molecular structure to phenylpropanolamine, methamphetamine, and epinephrine (adrenaline). Chemically, it is an alkaloid with a phenethylamine skeleton found in various plants in the genus Ephedra (family Ephedraceae). It works mainly by increasing the activity of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) on adrenergic receptors.[23] It is most usually marketed as the hydrochloride or sulfate salt.

Ephedrine exhibits optical isomerism and has two chiral centres, giving rise to four stereoisomers. By convention, the pair of enantiomers with the stereochemistry (1R,2S and 1S,2R) is designated ephedrine, while the pair of enantiomers with the stereochemistry (1R,2R and 1S,2S) is called pseudoephedrine. Ephedrine is a substituted amphetamine and a structural methamphetamine analogue. It differs from methamphetamine only by the presence of a hydroxyl group (OH).

The isomer which is marketed is (–)-(1R,2S)-ephedrine.[24]

Ephedrine hydrochloride has a melting point of 187−188 °C.[25]

In the outdated d/l system (+)-ephedrine is also referred to as l-ephedrine and (−)-ephedrine as d-ephedrine (in the Fisher projection, then the phenyl ring is drawn at bottom).[24][26]

Often, the d/l system (with small caps) and the d/l system (with lower-case) are confused. The result is that the levorotary l-ephedrine is wrongly named l-ephedrine and the dextrorotary d-pseudoephedrine (the diastereomer) wrongly d-pseudoephedrine.

The IUPAC names of the two enantiomers are (1R,2S)- respectively (1S,2R)-2-methylamino-1-phenylpropan-1-ol. A synonym is erythro-ephedrine.

Sources

Agricultural

Ephedrine is obtained from the plant Ephedra sinica and other members of the Ephedra genus. Raw materials for the manufacture of ephedrine and traditional Chinese medicines are produced in China on a large scale. As of 2007, companies produced for export US$13 million worth of ephedrine from 30,000 tons of ephedra annually, 10 times the amount used in traditional Chinese medicine.[29]

Synthetic

Most of the l-ephedrine produced today for official medical use is made synthetically as the extraction and isolation process from E. sinica is tedious and no longer cost effective.[30]

Biosynthetic

Ephedrine was long thought to come from modifying the amino acid L-Phenylalanine.[31] L-Phenylalanine would be decarboxylated and subsequently attacked with ω-aminoacetophenone. Methylation of this product would then produce ephedrine. This pathway has since been disproven.[31] A new pathway proposed suggests that phenylalanine first forms cinnamoyl-CoA via the enzymes phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and acyl CoA ligase.[27] The cinnamoyl-CoA is then reacted with a hydratase to attach the alcohol functional group. The product is then reacted with a retro-aldolase, forming benzaldehyde. Benzaldehyde reacts with pyruvic acid to attach a 2 carbon unit. This product then undergoes transamination and methylation to form ephedrine and its stereoisomer, pseudoephedrine.[28]

Mechanism of action

Ephedrine, a sympathomimetic amine, acts on part of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The principal mechanism of action relies on its indirect stimulation of the adrenergic receptor system by increasing the activity of norepinephrine at the postsynaptic α- and β-receptors.[23] The presence of direct interactions with α-receptors is unlikely, but still controversial.[8][32][33] L-Ephedrine, and particularly its stereoisomer norpseudoephedrine (which is also present in Catha edulis) has indirect sympathomimetic effects and due to its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, it is a CNS stimulant similar to amphetamines, but less pronounced, as it releases noradrenaline and dopamine in the substantia nigra.[34]

The presence of an N-methyl group decreases binding affinities at α-receptors, compared with norephedrine. Ephedrine, though, binds better than N-methylephedrine, which has an additional methyl group at the N-atom. Also the steric orientation of the hydroxyl group is important for receptor binding and functional activity.[32]

- Compounds with decreasing α-receptor affinity

History

Ephedrine in its natural form, known as má huáng (麻黄) in traditional Chinese medicine, has been documented in China since the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) as an antiasthmatic and stimulant.[35] In 1885, the chemical synthesis of ephedrine was first accomplished by Japanese organic chemist Nagai Nagayoshi based on his research on traditional Japanese and Chinese herbal medicines. The industrial manufacture of ephedrine in China began in the 1920s, when Merck began marketing and selling the drug as ephetonin. Ephedrine exports between China and the West grew from 4 to 216 tonnes between 1926 and 1928.[36]

In traditional Chinese medicine, má huáng has been used as a treatment for asthma and bronchitis for centuries.[37]

Legality

Canada

In January 2002, Health Canada issued a voluntary recall of all ephedrine products containing more than 8 mg per dose, all combinations of ephedrine with other stimulants such as caffeine, and all ephedrine products marketed for weight-loss or bodybuilding indications, citing a serious risk to health.[38] Ephedrine is still sold as an oral nasal decongestant in 8 mg pills, OTC.

United States

In 1997, the FDA proposed a regulation on ephedra (the herb from which ephedrine is obtained), which limited an ephedra dose to 8 mg (of active ephedrine) with no more than 24 mg per day.[39] This proposed rule was withdrawn, in part, in 2000 because of "concerns regarding the agency's basis for proposing a certain dietary ingredient level and a duration of use limit for these products."[40] In 2004, the FDA created a ban on ephedrine alkaloids marketed for reasons other than asthma, colds, allergies, other disease, or traditional Asian use.[41] On April 14, 2005, the U.S. District Court for the District of Utah ruled the FDA did not have proper evidence that low dosages of ephedrine alkaloids are actually unsafe,[42] but on August 17, 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in Denver upheld the FDA's final rule declaring all dietary supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids adulterated, and therefore illegal for marketing in the United States.[43] Furthermore, ephedrine is banned by the NCAA, MLB, NFL, and PGA.[44] Ephedrine is, however, still legal in many applications outside of dietary supplements. Purchasing is currently limited and monitored, with specifics varying from state to state.

The House passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 as an amendment to the renewal of the USA PATRIOT Act. Signed into law by President George W. Bush on March 6, 2006, the act amended the US Code (21 USC 830) concerning the sale of ephedrine-containing products. The federal statute included these requirements for merchants who sell these products:

- A retrievable record of all purchases identifying the name and address of each party to be kept for two years

- Required verification of proof of identity of all purchasers

- Required protection and disclosure methods in the collection of personal information

- Reports to the Attorney General of any suspicious payments or disappearances of the regulated products

- Non-liquid dose form of regulated product may only be sold in unit-dose blister packs

- Regulated products are to be sold behind the counter or in a locked cabinet in such a way as to restrict access

- Daily sales of regulated products not to exceed 3.6 g without regard to the number of transactions

- Monthly sales not to exceed 9 g of pseudoephedrine base in regulated products

The law gives similar regulations to mail-order purchases, except the monthly sales limit is only 7.5 g.

As a pure herb or tea, má huáng, containing ephedrine, is still sold legally in the USA. The law restricts/prohibits its being sold as a dietary supplement (pill) or as an ingredient/additive to other products, like diet pills.

Australia

All Ephedra spp and Ephedrine itself are considered schedule 4 substances under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[45] A schedule 4 drug is considered a Prescription Only Medicine, or Prescription Animal Remedy – Substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[45]

South Africa

In South Africa, ephedrine was moved to schedule 6 on 27 May 2008,[46] which makes the substance legal to possess but available by prescription only.

Germany

Ephedrine was freely available in pharmacies in Germany until 2001. Afterwards, access was restricted since it was mostly bought for unindicated uses. Similarly, ephedra can only be bought with a prescription. Since April 2006, all products, including plant parts, that contain ephedrine are only available with a prescription.[47]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Ephedrine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Jan 2016.

- ↑ Yaffe, Gerald G. Briggs, Roger K. Freeman, Sumner J. (2011). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation : a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 495. ISBN 9781608317080.

- 1 2 "Ephedrine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ Bagchi, edited by Debasis; Preuss, Harry G. (2013). Obesity epidemiology, pathophysiology, and prevention (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 692. ISBN 9781439854266.

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Ephedrine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved January 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 162. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 Drew; et al. (1978). "Comparison of the effects of D-(-)-ephedrine and L-(+)-pseudoephedrine on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in man" (PDF). Br J Clin Pharmacol 6 (3): 221–225. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb04588.x. PMC 1429447. PMID 687500.

- ↑ Shekelle, P. G.; Hardy, M. L.; Morton, S. C.; Maglione, M.; Mojica, W. A.; Suttorp, M. J.; Rhodes, S. L.; Jungvig, L.; Gagné, J. (2003). "Efficacy and Safety of Ephedra and Ephedrine for Weight Loss and Athletic Performance: A Meta-analysis". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association 289 (12): 1537–1545. doi:10.1001/jama.289.12.1537. PMID 12672771.

- ↑ Dwyer, J. T.; Allison, D. B.; Coates, P. M. (2005). "Dietary Supplements in Weight Reduction". Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105 (5): S80–S86. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.028. PMID 15867902.

- ↑ George A. Bray; Claude Bouchard (2004). Handbook of obesity. CRC Press. pp. 494–496. ISBN 978-0-8247-4773-2.

- ↑ Magkos, F.; Kavouras, S. A. (2004). "Caffeine and ephedrine: Physiological, metabolic and performance-enhancing effects". Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 34 (13): 871–889. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434130-00002. PMID 15487903.

- ↑ Microsoft Word - RedListE2007.doc

- ↑ http://list.wada-ama.org/list/s6-stimulants/

- ↑ Schier, JG; Traub, SJ; Hoffman, RS; Nelson, LS (2003). "Ephedrine-induced cardiac ischemia: exposure confirmed with a serum level". Clin. Toxicol 41: 849–853. doi:10.1081/clt-120025350.

- ↑ WADA. The World Anti-Doping Code, World Anti-Doping Agency, Montreal, Canada, 2010. url

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 542-544.

- 1 2 Mayne Pharma. Ephedrine sulfate injection DBL (Approved Product Information). Melbourne: Mayne Pharma; 2004

- ↑ Palamar J (January 2011). "How ephedrine escaped regulation in the United States: a historical review of misuse and associated policy". Health Policy (Review) 99 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.07.007. PMID 20685002.

- ↑ Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary, 47th edition. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2004. ISBN 0-85369-587-3

- ↑ Txsci.oxfordjournals (2000).

- ↑ Borsato, Giuseppe; Linden, Anthony; De Lucchi, Ottorino; Lucchini, Vittorio; Wolstenholme, David; Zambon, Alfonso (2007). "Chiral Polycyclic Ketones via Desymmetrization of Dihaloolefins". J. Org. Chem. 72 (11): 4272–4275. doi:10.1021/jo070222g.

- 1 2 Merck Manuals > EPHEDrine Last full review/revision January 2010

- 1 2 Martindale (1989). Edited by Reynolds JEF, ed. Martindale: The complete drug reference (29th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 0-85369-210-6.

- ↑ Budavari S, editor. The Merck Index: An encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals, 12th edition. Whitehouse Station: Merck

- ↑ Patil, Popat N.; Tye, A.; LaPidus, J.B. (1965). "A pharmacological study of the ephedrine isomers" (PDF). JPET 148 (2): 158–168.

- 1 2 Hertweck, Christian (October 1,). "A Mechanism of Benzoic Acid Biosynthesis in Plants and Bacteria that Mirrors Fatty Acid β-Oxidation". Chem Bio Chem. doi:10.1002/1439-7633(20011001)2:10<784::AID-CBIC784>3.0.CO;2-K. Retrieved 2015-06-10. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Grue-Sorensen, Gunnar.; Spenser, Ian D. (May 1, 1988). "Biosynthesis of ephedrine". Journal of the American Chemical Society 110 (11): 3714–3715. doi:10.1021/ja00219a086. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ↑ Long, Professor. http://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/692-Chinese-medicine-s-great-waste-of-resources

- ↑ Chemically Synthesized Ephedrine Put Into Mass Production in China

- 1 2 "Participation of C6-C1 unit in the biosynthesis of ephedrine in Ephedra". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- 1 2 Guoyi Ma, et al. Pharmacological Effects of Ephedrine Alkaloids on Human {alpha}1- and {alpha}2-Adrenergic Receptor Subtypes J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322: pp. 214-221 (july 2007) PDF

- ↑ Shigeaki Kobayashi, et al. The Sympathomimetic Actions of l-Ephedrine and d-Pseudoephedrine: Direct Receptor Activation or Norepinephrine Release? Anesth Analg 2003; 97, pp.1239-1245.

- ↑ Munhall, AC; Johnson, SW (2006). "Dopamine-mediated actions of ephedrine in the rat substantia nigra". Brain Res 1069 (1): 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.044. PMID 16386715.

- ↑ Woodburne O. Levy; Kavita Kalidas (26 February 2010). Norman S. Miller, ed. Principles of Addictions and the Law: Applications in Forensic, Mental Health, and Medical Practice. Academic Press. pp. 307–308. ISBN 978-0-12-496736-6.

- ↑ Frank Dikotter; Lars Peter Laamann (16 April 2004). Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China. University of Chicago Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-226-14905-9.

- ↑ Ford MD, Delaney KA, Ling LJ, Erickson T, editors. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001. ISBN 0-7216-5485-1 Research Laboratories; 1996. ISBN 0-911910-12-3

- ↑ "Health Canada requests recall of certain products containing Ephedra/ephedrine". Health Canada. January 9, 2002. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ↑ Federal Register: June 4, 1997 (Volume 62, Number 107): Dietary Supplements Containing Ephedrine Alkaloids; Proposed Rule

- ↑ Federal Register: April 3, 2000 (Volume 65, Number 64): Dietary Supplements Containing Ephedrine Alkaloids; Withdrawal in Part

- ↑ Federal Register: February 11, 2004 (Volume 69, Number 28): Final Rule Declaring Dietary Supplements Containing Ephedrine Alkaloids Adulterated Because They Present an Unreasonable Risk; Final Rule

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.drugfreesport.com/drug-resources/faq.asp

- 1 2 Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534

- ↑ http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/pr/2008/pr0527.html

- ↑ Verordnung zur Neuordnung der Verschreibungspflicht von Arzneimitteln (AMVVNV). V. v. 21. Dezember 2005 BGBl. I S. 3632; Geltung ab 1. Januar 2006.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|