Substrate (chemistry)

In chemistry, a substrate is typically the chemical species being observed in a chemical reaction, which reacts with reagent to generate a product. In synthetic and organic chemistry, the substrate is the chemical of interest that is being modified. In biochemistry, an enzyme substrate is the material upon which an enzyme acts. When referring to Le Chatelier's Principle, the substrate is the reagent whose concentration is changed. The term substrate is highly context-dependent.[1]

|

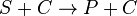

Spontaneous reaction

|

Catalysed reaction

|

Biochemistry

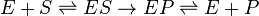

In biochemistry, the substrate is a molecule upon which an enzyme acts. Enzymes catalyze chemical reactions involving the substrate(s). In the case of a single substrate, the substrate bonds with the enzyme active site, and an enzyme-substrate complex is formed. The substrate is transformed into one or more products, which are then released from the active site. The active site is then free to accept another substrate molecule. In the case of more than one substrate, these may bind in a particular order to the active site, before reacting together to produce products. A substrate is called 'chromogenic', if it gives rise to a colored product when acted on by an enzyme. In histological enzyme localization studies, the colored product of enzyme action can be viewed under a microscope, in thin sections of biological tissues.

For example, curd formation (rennet coagulation) is a reaction that occurs upon adding the enzyme rennin to milk. In this reaction, the substrate is a milk protein (e.g., casein) and the enzyme is rennin. The products are two polypeptides that have been formed by the cleavage of the larger peptide substrate. Another example is the chemical decomposition of hydrogen peroxide carried out by the enzyme catalase. As enzymes are catalysts, they are not changed by the reactions they carry out. The substrate(s), however, is/are converted to product(s). Here, hydrogen peroxide is converted to water and oxygen gas.

- Where E is enzyme, S is substrate, and P is product

While the first (binding) and third (unbinding) steps are, in general, reversible, the middle step may be irreversible (as in the rennin and catalase reactions just mentioned) or reversible (e.g. many reactions in the glycolysis metabolic pathway).

By increasing the substrate concentration, the rate of reaction will increase due to the likelihood that the number of enzyme-substrate complexes will increase; this occurs until the enzyme concentration becomes the limiting factor.

Substrate promiscuity

Although enzymes are typically highly specific, some are able to perform catalysis on more than one substrate, a property termed enzyme promiscuity. An enzyme may have many native substrates and broad specificity (e.g. oxidation by cytochrome p450s) or it may have a single native substrate with a set of similar non-native substrates that it can catalyse at some lower rate. The substrates that a given enzyme may react with in vitro, in a laboratory setting, may not necessarily reflect the physiological, endogenous substrates of the enzyme's reactions in vivo. That is to say that enzymes do not necessarily perform all the reactions in the body that may be possible in the laboratory. For example, while fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) can hydrolyze the endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide at comparable rates in vitro, genetic or pharmacological disruption of FAAH elevates anandamide but not 2-AG, suggesting that 2-AG is not an endogenous, in vivo substrate for FAAH.[2] In another example, the N-acyl taurines (NATs) are observed to increase dramatically in FAAH-disrupted animals, but are actually poor in vitro FAAH substrates.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "substrate".

- ↑ Cravatt, B.F.; Demarest, K.; Patricelli, M.P.; Bracey, M.H.; Gaing, D.K.; Martin, B.R.; Lichtman, A.H. (2001). "Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 (16): 9371–9376. doi:10.1073/pnas.161191698. PMC 55427. PMID 11470906.

- ↑ Saghatelian, A.; Trauger, S.A.; Want, E.J.; Hawkins, E.G.; Siuzdak, G.; Cravatt, B.F. (2004). "Assignment of Endogenous Substrates to Enzymes by Global Metabolite Profiling". Biochemistry 43 (45): 14322–14339. doi:10.1021/bi0480335. PMID 15533037.