Vitreous enamel

Vitreous enamel, also called porcelain enamel, is a material made by fusing powdered glass to a substrate by firing, usually between 750 and 850 °C (1,380 and 1,560 °F). The powder melts, flows, and then hardens to a smooth, durable vitreous coating on metal, or on glass or ceramics.

The term "enamel" is most often restricted to work on metal, which is the subject of this article. Enameled glass is also called "painted". Fired enamelware is an integrated layered composite of glass and metal.

The word enamel comes from the Old High German word smelzan (to smelt) via the Old French esmail,[1] or from a Latin word smaltum, first found in a 9th-century life of Leo IV.[2] Used as a noun, "an enamel" is usually a small decorative object coated with enamel.

Enameling is an old and widely adopted technology, for most of its history mainly used in jewelry and decorative art.

Since the 19th century the term applies also to industrial materials and many metal consumer objects, such as some cooking vessels, dishwashers, laundry machines, sinks, and tubs. ("Enamelled" and "enamelling" are the preferred spellings in British English, while "enameled" and "enameling" are preferred in American English.)

History

.jpg)

Ancient Persians used this method for coloring and ornamenting the surface of metals by fusing over it brilliant colors that are decorated in an intricate design and called it Meenakari.

Mina is the feminine form of Minoo in Persian, meaning heaven. Mina refers to the Azure color of heaven. The Iranian craftsmen of Sasanian Empire era invented this art and Mongols spread it to India and other countries.[3] The ancient Egyptians applied enamels to stone objects, pottery, and sometimes jewelry, though to the last less often than in other ancient Middle Eastern cultures.

The ancient Greeks, Celts, Georgians, and Chinese also used enamel on metal objects.[4]

Enamel was also used to decorate glass vessels during the Roman period, and there is evidence of this as early as the late Republican and early Imperial periods in the Levant, Egypt, Britain and around the Black Sea.[5] Enamel powder could be produced in two ways, either by powdering colored glass, or by mixing colorless glass powder with pigments such as a metallic oxide.[6]

Designs were either painted freehand or over the top of outline incisions, and the technique probably originated in metalworking.[5] Once painted, enameled glass vessels needed to be fired at a temperature high enough to melt the applied powder, but low enough that the vessel itself was not melted.

Production is thought to have come to a peak in the Claudian period and persisted for some three hundred years,[5] though archaeological evidence for this technique is limited to some forty vessels or vessel fragments.[5] French tourist, Jean Chardin, who toured Iran during the Safavid rule, made a reference to an enamel work of Isfahan, which comprised a pattern of birds and animals on a floral background in light blue, green, yellow and red. Gold has been used traditionally for Meenakari Jewellery as it holds the enamel better, lasts longer and its luster brings out the colors of the enamels.

Silver, a later introduction, is used for artifacts like boxes, bowls, spoons, and art pieces while Copper which is used for handicraft products were introduced only after the Gold Control Act, which compelled the Meenakars to look for a material other than gold, was enforced in India.[3]

Initially, the work of Meenakari often went unnoticed as this art was traditionally used as a backing for the famous kundan or stone-studded jewellery. This also allowed the wearer to reverse the jewelry as also promised a special joy in the secret of the hidden design.[7]

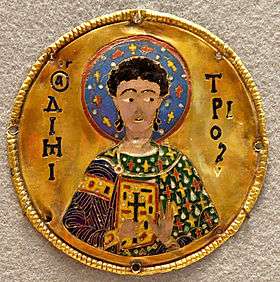

In European art history, enamel was at its most important in the Middle Ages, beginning with the Late Romans and then the Byzantines, who began to use cloisonné enamel in imitation of cloisonné inlays of precious stones. This style was widely adopted by the "barbarian" peoples of Migration Period northern Europe. The Byzantines then began to use cloisonné more freely to create images; this was also copied in Western Europe. The champlevé technique was considerably easier and very widely practiced in the Romanesque period. In Gothic art the finest work is in basse-taille and ronde-bosse techniques, but cheaper champlevé works continued to be produced in large numbers for a wider market.

From either Byzantium or the Islamic world, the cloisonné technique reached China in the 13-14th centuries. The first written reference to cloisonné is in a book from 1388, where it is called "Dashi ('Muslim') ware".[8] No Chinese pieces that are clearly from the 14th century are known; the earliest datable pieces are from the reign of the Xuande Emperor (1425–35), which, since they show a full use of Chinese styles, suggest considerable experience in the technique.

Cloisonné remained very popular in China until the 19th century and is still produced today. The most elaborate and most highly valued Chinese pieces are from the early Ming Dynasty, especially the reigns of the Xuande Emperor and Jingtai Emperor (1450–57), although 19th century or modern pieces are far more common.[9] Starting from the mid-19th century, the Japanese also produced large quantities of very high technical quality.[10]

More recently, the bright, jewel-like colors have made enamel a favored choice for jewelry designers, including the Art Nouveau jewelers, for designers of bibelots such as the eggs of Peter Carl Fabergé and the enameled copper boxes of the Battersea enamellers, and for artists such as George Stubbs and other painters of portrait miniatures.

A resurgence in enamel-based art took place near the end of the 20th century in the Soviet Union, led by artists like Alexei Maximov and Leonid Efros. In Australia, abstract artist Bernard Hesling brought the style into prominence with his variously sized steel plates.[11]

Enamel was first applied commercially to sheet iron and steel in Austria and Germany in about 1850.[12] Industrialization increased as the purity of raw materials increased and costs decreased. The wet application process started with the discovery of the use of clay to suspend frit in water. Developments that followed during the 20th century include enameling-grade steel, cleaned-only surface preparation, automation, and ongoing improvements in efficiency, performance, and quality.[13]

Properties

Vitreous enamel can be applied to most metals. Most modern industrial enamel is applied to steel in which the carbon content is controlled to prevent unwanted reactions at the firing temperatures. Enamel can also be applied to copper, aluminium,[14] stainless steel,[15] cast iron or hot rolled steel,[16] as well as to gold and silver.

Vitreous enamel has many excellent properties: it is smooth, hard, chemically resistant, durable, scratch resistant (5-6 on the Mohs scale), has long-lasting color fastness, is easy to clean, and cannot burn. Enamel is glass, not paint, so it does not fade under ultraviolet light.[17] A disadvantage of enamel is a tendency to crack or shatter when the substrate is stressed or bent, but modern enamels are relatively chip- and impact-resistant because of good thickness control and thermal expansions well-matched to the metal. The Buick automobile company was founded by David Dunbar Buick with wealth earned by his development of improved enameling processes, circa 1887, for sheet steel and cast iron. Such enameled ferrous material had, and still has, many applications: early 20th century and some modern advertising signs, interior oven walls, cooking pots, housing and interior walls of major kitchen appliances, housing and drums of clothes washers and dryers, sinks and cast iron bathtubs, farm storage silos, and processing equipment such as chemical reactors and pharmaceutical process tanks. Structures such as filling stations, bus stations and Lustron Houses had walls, ceilings and structural elements made of enameled steel. One of the most widespread modern uses of enamel is in the production of quality chalk-boards and marker-boards (typically called 'blackboards' or 'whiteboards') where the resistance of enamel to wear and chemicals ensures that 'ghosting', or unerasable marks, do not occur, as happens with polymer boards. Since standard enameling steel is magnetically attractive, it may also be used for magnet boards. Some new developments in the last ten years include enamel/non-stick hybrid coatings, sol-gel functional top-coats for enamels, enamels with a metallic appearance, and new easy-to-clean enamels.[18]

The key ingredient of vitreous enamel is a highly friable form of glass called frit. Frit is typically an alkali borosilicate chemical with a thermal expansion and glass temperature suitable for coating steel. Raw materials are smelted together between 2,100 and 2,650 °F (1,150 and 1,450 °C) into a liquid glass that is directed out of the furnace and thermal shocked with either water or steel rollers into frit.[19]

Color in enamel is obtained by the addition of various minerals, often metal oxides cobalt, praseodymium, iron, or neodymium. The latter creates delicate shades ranging from pure violet through wine-red and warm gray. Enamel can be transparent, opaque or opalescent (translucent), which is a variety that gains a milky opacity with longer firing. Different enamel colors cannot be mixed to make a new color, in the manner of paint.

There are three main types of frit, usually applied in sequence. A ground coat is applied first; it usually contains smelted-in transition metal oxides such as cobalt, nickel, copper, manganese, and iron that facilitate adhesion to steel. Next, clear and semi-opaque frits that contain material for producing colors are applied. Finally, a titanium white cover coat frit, supersaturated with titanium dioxide, creating a bright white color during firing, is applied as the exterior coat.

After smelting, the frit needs to be processed into one of the three main forms of enamel coating material. First, wet process enamel slip (or slurry) is a high solids loading product achieved by grinding the frit with clay and other viscosity-controlling electrolytes. Second, ready-to-use (RTU) is a cake-mix form of the wet process slurry that is ground dry and can be reconstituted by mixing with water at high shear. Finally, electrostatic powder that can be applied as a powder coating is produced by milling frit with a trace level of proprietary additives. The frit may also be ground as a powder or into a paste for jewelry or silk-screening applications.

-

View into a glass-lined chemical reactor

-

Turb-mixer in a glass-lined chemical reactor

Techniques of artistic enameling

- Basse-taille, from the French word meaning "low-cut". The surface of the metal is decorated with a low relief design which can be seen through translucent and transparent enamels. The 14th century Royal Gold Cup is an outstanding example.[20]

- Champlevé, French for "raised field", where the surface is carved out to form pits in which enamel is fired, leaving the original metal exposed; the Romanesque Stavelot Triptych is an example.[21]

- Cloisonné, French for "cell", where thin wires are applied to form raised barriers, which contain different areas of (subsequently applied) enamel. Widely practiced in Europe, the Middle East and East Asia.[22]

- En résille (Émail en résille sur verre, French for 'enamel in a network on glass,') where enameled metal is suspended in glass. The technique was briefly popular in seventeenth-century France and was re-discovered by Margret Craver in 1953. Craver spent 13 years re-creating the technique.[23]

- Grisaille, French term meaning "in grey", where a dark, often blue or black background is applied, then a palescent (translucent) enamel is painted on top, building up designs in a monochrome gradient, paler as the thickness of the layer of light color increases.

- Limoges enamel, made at Limoges, France, a famous center of vitreous enamel production. Limoges became famous for champlevé enamels from the 12th century onwards, producing on a large scale, and then from the 15th century retained its lead by switching to painted enamel on flat metal plaques.

- Painted enamel, a design in enamel is painted onto a smooth metal surface. Grisaille and later Limoges enamel are types of painted enamel.[24] Most traditional painting on glass, and some on ceramics, uses what is technically enamel, but is often described by terms such as "painted in enamels", reserving "painted enamel" and "enamel" as a term for the whole object for works with a metal base.[25]

- Plique-à-jour, French for "open to daylight" where the enamel is applied in cells, similar to cloisonné, but with no backing, so light can shine through the transparent or translucent enamel. It has a stained-glass like appearance; the Mérode Cup is the surviving medieval example.[26]

- Ronde bosse, French for "in the round", also known as "encrusted enamel". A 3D type of enameling where a sculptural form or wire framework is completely or partly enameled, as in the 15th century Holy Thorn Reliquary.[27]

- Stenciling, where a stencil is placed over the work and the powdered enamel is sifted over the top. The stencil is removed before firing, the enamel staying in a pattern, slightly raised.

- Sgraffito, where an unfired layer of enamel is applied over a previously fired layer of enamel of a contrasting color, and then partly removed with a tool to create the design.

- Serigraph, where a silkscreen is used with 60-70in grade mesh.

- Counter enameling, not strictly a technique, but a necessary step in many techniques, is to apply enamel to the back of a piece as well - sandwiching the metal - to create less tension on the glass so it does not crack.

Industrial enamel application

On sheet steel, a ground coat layer is applied to create adhesion. The only surface preparation required for modern ground coats is degreasing of the steel with a mildly alkaline solution. White and colored second "cover" coats of enamel are applied over the fired ground coat. For electrostatic enamels, the colored enamel powder can be applied directly over a thin unfired ground coat "base coat" layer that is co-fired with the cover coat in a very efficient two-coat/one-fire process.

The frit in the ground coat contains smelted-in cobalt and/or nickel oxide as well as other transition metal oxides to catalyze the enamel-steel bonding reactions. During firing of the enamel at between 760 to 895 °C (1,400 to 1,643 °F), iron oxide scale first forms on the steel. The molten enamel dissolves the iron oxide and precipitates cobalt and nickel. The iron acts as the anode in an electrogalvanic reaction in which the iron is again oxidized, dissolved by the glass, and oxidized again with the available cobalt and nickel limiting the reaction. Finally, the surface becomes roughened with the glass anchored into the holes.[28]

Building cladding

Enamel coatings applied to steel panels offer the most stringent protection to the core material whether cladding road tunnels, underground stations, building superstructures or other applications. It can also be specified as a curtain walling. Qualities of this structural material include:[29]

- Extremely durable

- Withstands extreme temperatures and is non-flammable

- Long lasting UV, climate and corrosion resistant

- Dirt-repellent and graffiti-proof

- Highly abrasive and chemical resistant

- Easy cleaning and maintenance

Gallery

-

Silver, silver gilt and painted enamel beaker, Burgundian Netherlands, c. 1425-1450, The Cloisters

-

The Royal Gold Cup with basse-taille enamels; weight 1.935 kg, British Museum. Saint Agnes appears to her friends in a vision.

-

A freehand enameled painting by Einar Hakonarson In the forest. 1989

-

St. Gregory the Great in painted Limoges enamel on a copper plaque, by Jacques I Laudin

-

Early 13th century Limoges chasse used to hold holy oils; most were reliquaries.

-

Medallion of the Death of the Virgin, with basse-taille enamel

-

The Dunstable Swan Jewel, a livery badge in ronde bosse enamel, about 1400. British Museum

-

Louis George enamel watch dial

-

Iranian enamel

-

Limoges? grisaille Stations of the Cross, Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Avranches

See also

- Ceramic glaze

- Nineveh

- Rostov the Great — a city renowned for its enamel work

- Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, a 2nd-century bronze trulla

- Franz Ullrich — founder of a German enamelware factory

- Oskar Schindler

- Fred Uhl Ball — American enamelist who created the largest known enamel mural

Notes

- ↑ Campbell, 6

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Enamel". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Enamel". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - 1 2 Meenakari

- ↑ Andrews, A.I. Porcelain Enamels, The Garrard Press: Champaign, IL, 1961 p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Rutti, B., Early Enamelled Glass, in Roman Glass: two centuries of art and invention, M. Newby and K. Painter, Editors. 1991, Society of Antiquaries of London: London.

- ↑ Gudenrath, W., Enameled Glass Vessels, 1425 BCE - 1800: The decorating Process. Journal of Glass Studies, 2006. 48

- ↑ http://www.iranreview.org/content/Documents/The_Art_of_Minakari_2.htm

- ↑ Sullivan, Michael, The arts of China, 4th edn, p. 239, University of California Press, 1999, Page 239

- ↑ Sullivan, Michael, The arts of China, 4th edn, p. 239, University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-21877-9, ISBN 978-0-520-21877-2, Google books

- ↑ "Japanese Cloisonné: the Seven Treasures". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ↑ database and e-research tool for art and design researchers. "Bernard Hesling :: biography at :: at Design and Art Australia Online". Daao.org.au. Retrieved 2013-12-25.

- ↑ Andrews, Andrew Irving, Porcelain enamels: the preparation, application, and properties of enamels, Garrard Press, 1961, Page 5

- ↑ Andrews, A.I. Porcelain Enamels, The Garrard Press: Champaign, IL, 1961 p. 5.

- ↑ Judd, Donald, “Porcelain Enameling Aluminum: An Overview,” Proceedings of the 59th Porcelain Enamel Institute Technical Forum, 45-51 (1997).

- ↑ Sullivan, J.D. and Nelson, F.W., "Stainless Steel Requires Special Enameling Procedures", Proceedings of the Porcelain Enamel Institute Technical Forum," 150-155 (1970).

- ↑ Pew, Steve, "The Who, What, Why, Where, and When of Cast Iron Enameling," Advances in Porcelain Enamel Technology, 177-186, (2010).

- ↑ Fedak, David and Baldwin, Charles, "A Comparison of Enameled and Stainless Steel Surfaces," Proceedings of the 67th Porcelain Enamel Institute Technical Forum, 45-54 (2005).

- ↑ Gavlenski, Jim and Baldwin, Charles, "Advanced Porcelain Enamel Coatings with Novel Properties," Proceedings of the 69th Porcelain Enamel Institute Technical Forum, 53-58, (2007).

- ↑ Andrews, A.I. Porcelain Enamels, The Garrard Press: Champaign, IL, 1961 p. 321-2.

- ↑ Campbell, 7, 33-41

- ↑ Campbell, 7, 17-32

- ↑ Campbell, 6, 10-17

- ↑ "Craft: Jewelry: Brooch". Luce Foundation Center for American Art. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ Campbell, 7

- ↑ British Museum collection database, "Scope note" for the term "enamelled"; other sources use different categories.

- ↑ Campbell, 38-42

- ↑ Campbell, 7, 42

- ↑ Feldman, Sid and Baldwin, Charles, "Surface Tension and Fusion Properties of Porcelain Enamels," Proceedings of the 69th Porcelain Enamel Institute Technical Forum, 1-10 (2008)

- ↑ Vitreous and porcelain enamels — Characteristics of enamel coatings applied to steel panels intended for architecture. Standards Policy and Strategy Committee. 2008. ISBN 978 0 580 72284 4.

References

- Campbell, Marian. An Introduction to Medieval Enamels, 1983, HMSO for V&A Museum, ISBN 0-11-290385-1

Further reading

- "Collection Highlights: Art in the Islamic World". Beaker. Smithsonian Institution: 2013.

- Dimand, M. S. "An Enameled-Glass Bottle of the Mamluk Period". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Papadopoulous, Kiko. "Venetian Eastern Trade: 11th to 14th Centuries" 20 January 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enamel. |

- Enamels on jewelry - historical

- Enameling Articles and Tutorials at The Ganoksin Project

- Mechanical and Physical Properties of Vitreous Enamel

- Glass on Metal Magazine Online (US)

- CIDAE Center of Information and Difusion of the Art of Enamelling (ES)

- EEA European Enamel Authority (EU)

- Society of Dutch Enamellers (NL)

- The Enamelist Society (US)

- Guild of Enamellers, UK

- Porcelain Enamel Institute (US)

- International Enamellers Institute

- Vitreous Enamel Association (UK)

- Ceramic Cladding

- Open Forum for all Enamellers

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|