Embodied energy

Embodied energy is the sum of all the energy required to produce any goods or services, considered as if that energy was incorporated or 'embodied' in the product itself. The concept can be useful in determining the effectiveness of energy-producing or energy-saving devices, or the "real" replacement cost of a building, and, because energy-inputs usually entail greenhouse gas emissions, in deciding whether a product contributes to or mitigates global warming. One fundamental purpose for measuring this quantity is to compare the amount of energy produced or saved by the product in question to the amount of energy consumed in producing it.

Embodied energy is an accounting method which aims to find the sum total of the energy necessary for an entire product life-cycle. Determining what constitutes this life-cycle includes assessing the relevance and extent of energy into raw material extraction, transport, manufacture, assembly, installation, disassembly, deconstruction and/or decomposition as well as human and secondary resources. Different methodologies produce different understandings of the scale and scope of application and the type of energy embodied.

History

The history of constructing a system of accounts which records the energy flows through an environment can be traced back to the origins of accounting itself. As a distinct method, it is often associated with the Physiocrat's "substance" theory of value,[1] and later the agricultural energetics of Sergei Podolinsky, a Ukrainian physician,[2] and the ecological energetics of Vladmir Stanchinsky.[3]

The main methods of embodied energy accounting as they are used today grew out of Wassily Leontief's input-output model and are called Input-Output Embodied Energy analysis. Leontief's input-output model was in turn an adaptation of the neo-classical theory of general equilibrium with application to "the empirical study of the quantitative interdependence between interrelated economic activities".[4] According to Tennenbaum[5] Leontief's Input-Output method was adapted to embodied energy analysis by Hannon[6] to describe ecosystem energy flows. Hannon’s adaptation tabulated the total direct and indirect energy requirements (the energy intensity) for each output made by the system. The total amount of energies, direct and indirect, for the entire amount of production was called the embodied energy.

Embodied energy methodologies

Embodied energy analysis is interested in what energy goes to supporting a consumer, and so all energy depreciation is assigned to the final demand of consumer. Different methodologies use different scales of data to calculate energy embodied in products and services of nature and human civilization. International consensus on the appropriateness of data scales and methodologies is pending. This difficulty can give a wide range in embodied energy values for any given material. In the absence of a comprehensive global embodied energy public dynamic database, embodied energy calculations may omit important data on, for example, the rural road/highway construction and maintenance needed to move a product, human marketing, advertising, catering services, non-human services and the like. Such omissions can be a source of significant methodological error in embodied energy estimations.[7] Without an estimation and declaration of the embodied energy error, it is difficult to calibrate the sustainability index, and so the value of any given material, process or service to environmental and human economic processes.

Standards

The SBTool, UK Code for Sustainable Homes and USA LEED are methods in which the embodied energy of a product or material is rated, along with other factors, to assess a building's environmental impact. Embodied energy is a concept for which scientists have not yet agreed absolute universal values because there are many variables to take into account, but most agree that products can be compared to each other to see which has more and which has less embodied energy. Comparative lists (for an example, see the University of Bath Embodied Energy & Carbon Material Inventory[8]) contain average absolute values, and explain the factors which have been taken into account when compiling the lists.

Typical embodied energy units used are MJ/kg (megajoules of energy needed to make a kilogram of product), tCO2 (tonnes of carbon dioxide created by the energy needed to make a kilogram of product). Converting MJ to tCO2 is not straightforward because different types of energy (oil, wind, solar, nuclear and so on) emit different amounts of carbon dioxide, so the actual amount of carbon dioxide emitted when a product is made will be dependent on the type of energy used in the manufacturing process. For example, the Australian Government[9] gives a global average of 0.098 tCO2 = 1 GJ. This is the same as 1 MJ = 0.098 kgCO2 = 98 gCO2 or 1 kgCO2 = 10.204 MJ.

Related methodologies

In the 2000s drought conditions in Australia have generated interest in the application of embodied energy analysis methods to water. This has led to use of the concept of embodied water.

Embodied energy in common materials

Selected data from the Inventory of Carbon and Energy ('ICE') prepared by the University of Bath (UK) [8]

| Material | Energy MJ per kg | Carbon kg CO2 per kg | Density kg /m3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate | 0.083 | 0.0048 | 2240 |

| Concrete (1:1.5:3) | 1.11 | 0.159 | 2400 |

| Bricks (common) | 3 | 0.24 | 1700 |

| Concrete block (Medium density) | 0.67 | 0.073 | 1450 |

| Aerated block | 3.5 | 0.3 | 750 |

| Limestone block | 0.85 | 2180 | |

| Marble | 2 | 0.116 | 2500 |

| Cement mortar (1:3) | 1.33 | 0.208 | |

| Steel (general, av. recycled content) | 20.1 | 1.37 | 7800 |

| Stainless steel | 56.7 | 6.15 | 7850 |

| Timber (general, excludes sequestration) | 8.5 | 0.46 | 480–720 |

| Glue laminated timber | 12 | 0.87 | |

| Cellulose insulation (loose fill) | 0.94–3.3 | 43 | |

| Cork insulation | 26 | 160 | |

| Glass fibre insulation (glass wool) | 28 | 1.35 | 12 |

| Flax insulation | 39.5 | 1.7 | 30 |

| Rockwool (slab) | 16.8 | 1.05 | 24 |

| Expanded Polystyrene insulation | 88.6 | 2.55 | 15–30 |

| Polyurethane insulation (rigid foam) | 101.5 | 3.48 | 30 |

| Wool (recycled) insulation | 20.9 | 25 | |

| Straw bale | 0.91 | 100–110 | |

| Mineral fibre roofing tile | 37 | 2.7 | 1850 |

| Slate | 0.1–1.0 | 0.006–0.058 | 1600 |

| Clay tile | 6.5 | 0.45 | 1900 |

| Aluminium (general & incl 33% recycled) | 155 | 8.24 | 2700 |

| Bitumen (general) | 51 | 0.38–0.43 | |

| Medium-density fibreboard | 11 | 0.72 | 680–760 |

| Plywood | 15 | 1.07 | 540–700 |

| Plasterboard | 6.75 | 0.38 | 800 |

| Gypsum plaster | 1.8 | 0.12 | 1120 |

| Glass | 15 | 0.85 | 2500 |

| PVC (general) | 77.2 | 2.41 | 1380 |

| Vinyl flooring | 65.64 | 2.92 | 1200 |

| Terrazzo tiles | 1.4 | 0.12 | 1750 |

| Ceramic tiles | 12 | 0.74 | 2000 |

| Wool carpet | 106 | 5.53 | |

| Wallpaper | 36.4 | 1.93 | |

| Vitrified clay pipe (DN 500) | 7.9 | 0.52 | |

| Iron (general) | 25 | 1.91 | 7870 |

| Copper (average incl. 37% recycled) | 42 | 2.6 | 8600 |

| Lead (incl 61% recycled) | 25.21 | 1.57 | 11340 |

| Ceramic sanitary ware | 29 | 1.51 | |

| Paint - Water-borne | 59 | 2.12 | |

| Paint - Solvent-borne | 97 | 3.13 |

| Photovoltaic (PV) Cells Type | Energy MJ per m2 | Carbon kg CO2 per m2 |

| Monocrystalline (average) | 4750 | 242 |

| Polycrystalline (average) | 4070 | 208 |

| Thin film (average) | 1305 | 67 |

Embodied energy in automobiles

Manufacturing

According to Volkswagen, the embodied energy contents of a Golf A3 with a petrol engine amounts to 18 000 kWh (i.e. 12% of 545 GJ as shown in the report[10]). A Golf A4 (equipped with a turbocharged direct injection) will show an embodied energy amounting to 22 000 kWh (i.e. 15% of 545 GJ as shown in the report[10]). According to the French energy and environment agency ADEME [11] a motor car has an embodied energy contents of 20 800 kWh whereas an electric vehicle shows an embodied energy contents amounting to 34 700 kWh.

Fuel

As regards energy itself, the fuel EROEI can be estimated at 8, which means that the embodied energy of the fuel approximately amounts to 1/7 of the fuel consumption. Put in other words, the fuel consumption should be augmented by 14% due to the fuel EROEI.

Road construction

We have to work here with figures, which prove still more difficult to obtain. In the case of road construction, the embodied energy would amount to 1/18 of the fuel consumption (i.e. 6%).[12]

Overall embodied energy of a car

The environmental calculator of the French environment and energy agency shows the usual fuel consumption of different means of transportation. If an embodied energy of 20 000 kWh is assumed, when taking a distance of 200 000 km into account, 10 kWh or one liter gasoline has to be added to the consumption. Moreover, the EROEI and the road construction represent approximately 20% of the fuel consumption. For a consumption of 6,4 l/100 km, it means that the corresponding embodied energy is equal to 1.3 l/100 km, so that the overall embodied energy amounts to 2.3 l/100 km.

Other figures available

Treloar, et al. have estimated the embodied energy in an average automobile in Australia as 0.27 terajoules (i.e. 75 000 kWh) as one component in an overall analysis of the energy involved in road transportation.[13]

Embodied energy in the energy field

EROEI provides a basis for evaluating the embodied energy due to energy.

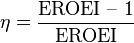

Thanks to EROEI definition, it is possible to evaluate the efficiency  according to

according to

Under these circumstances, final energy has to be multiplied by  in order to get primary energy.

in order to get primary energy.

Given an EROEI amounting to eight e.g., a seventh of the final energy has to be added to the final energy for obtaining primary energy.

Not only that, for really obtaining overall embodied energy, embodied energy due to the construction and maintenance of power plants should be taken into account, too. Here, figures are badly needed.

In France, by convention, EROEI related to electricity is equal to 2.58/1.58,[14] i.e. 1.633

corresponding to an efficiency of 0.3875 or 38.8%. Moreover, if the grid efficiency is evaluated at 92.5%,[14] overall electricity efficiency in France amounts to 35.8%.

See also

References

- ↑ Mirowski, Philip (1991). More Heat Than Light: Economics as Social Physics, Physics as Nature's Economics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 154–163. ISBN 978-0-521-42689-3.

- ↑ Martinez-Alier, J. (1990). Ecological Economics: Energy Environment and Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631171460.

- ↑ Weiner, Douglas R. (2000). Models of Nature: Ecology, Conservation, and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia. University of Pittsburgh Pre. pp. 70–71, 78–82. ISBN 978-0-8229-7215-0.

- ↑ Leontief, W. (1966). Input-Output Economics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 134.

- ↑ Tennenbaum, Stephen E. (1988). Network Energy Expenditures for Subsystem Production (PDF) (MS). OCLC 20211746. Docket CFW-88-08.

- ↑ Hannon, B. (October 1973). "The Structure of ecosystems" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology 41 (3): 535–546. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(73)90060-X.

- ↑ Lenzen 2001

- 1 2 G.P.Hammond and C.I.Jones (2006) Embodied energy and carbon footprint database, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bath, United Kingdom

- ↑ CSIRO on embodied energy: Australia's foremost scientific institution

- 1 2 (de) Volkswagen environmental report 2001/2002 see page 27

- ↑ (fr) Life cycle assessment website www.ademe.fr see page 9

- ↑ energy-and-road-construction website www.pavementinteractive.org

- ↑ Hybrid life-cycle inventory for road construction and use website resaerchgate.net

- 1 2 (fr) fr:Microcogénération#Notions de rendements, d'efficacité et de ratio électricité / chaleur

Bibliography

- Clark, D.H.; Treloar, G.J.; Blair, R. (2003). "Estimating the increasing cost of commercial buildings in Australia due to greenhouse emissions trading". In Yang, J.; Brandon, P.S.; Sidwell, A.C. Proceedings of The CIB 2003 International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, Brisbane, Australia. ISBN 1741070414. OCLC 224896901.

- Costanza, R. (1979). Embodied Energy Basis for Economic-Ecologic Systems (Ph.D.). University of Florida. OCLC 05720193. UF00089540:00001.

- Crawford, R.H. (2005). "Validation of the Use of Input-Output Data for Embodied Energy Analysis of the Australian Construction Industry". Journal of Construction Research 6 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1142/S1609945105000250.

- Lenzen, M. (2001). "Errors in conventional and input-output-based life-cycle inventories". Journal of Industrial Ecology 4 (4): 127–148. doi:10.1162/10881980052541981.

- Lenzen, M.; Treloar, G.J. (February 2002). "Embodied energy in buildings: wood versus concrete-reply to Börjesson and Gustavsson". Energy Policy 30 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(01)00142-2.

- Treloar, G.J. (1997). "Extracting Embodied Energy Paths from Input-Output Tables: Towards an Input-Output-based Hybrid Energy Analysis Method". Economic Systems Research 9 (4): 375–391. doi:10.1080/09535319700000032.

- Treloar, Graham J. (1998). A comprehensive embodied energy analysis framework (Ph.D.). Deakin University.

- Treloar, G.J.; Owen, C.; Fay, R. (2001). "Environmental assessment of rammed earth construction systems". Structural survey 19 (2): 99–105. doi:10.1108/02630800110393680.

- Treloar, G.J.; Love, P.E.D.; Holt, G.D. (2001). "Using national input-output data for embodied energy analysis of individual residential buildings". Construction Management and Economics 19 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/014461901452076.

External links

- Research on embodied energy at the University of Sydney, Australia

- Australian Greenhouse Office, Department of the Environment and Heritage

- University of Bath (UK), Inventory of Carbon & Energy (ICE) Material Inventory

- eTool LTD, Embodied Energy Calculations within Life Cycle Analysis of Residential Buildings