Embodied bilingual language

Embodied bilingual language, also known as L2 embodiment, is the idea that people mentally simulate their actions, perceptions, and emotions when speaking and understanding a second language (L2) as with their first language (L1).[1] It is closely related to embodied cognition and embodied language processing, both of which only refer to native language thinking and speaking. An example of embodied bilingual language would be situation in which a L1 English speaker learning Spanish as a second language hears the word rápido (“fast”) in Spanish while taking notes and then proceeds to take notes more quickly.

Overview

Embodied bilingual language refers to the role second language learning plays in embodied cognition, which proposes that the way the body interacts with its environment influences the way a person thinks or creates mental images.[2]

Embodied cognition theory assumes that embodiment occurs automatically and in a person’s native tongue.[3] Embodied theories of language posit that word meaning is grounded in mental representations of action, perception, and emotion.[2] Thus, L2 embodiment presupposes that embodied cognition takes place in a language that was learned later in life, outside of a child’s critical period of learning a language. In embodied bilingual language, a second language as well as the first language connects cognition with physical body movements.[1]

For example, in first language (L1) embodiment, research shows that participants are quicker to comprehend sentences if they are simultaneously presented with pictures describing the actions in the sentence.[4] Embodied language assumes that comprehension of language requires mental simulation, or imagination, of the subject and action of a sentence that is being processed and understood. Following L1 embodiment, L2 embodiment supposes that the understanding of sentences in L2 also require the same mental processes that underlie first language comprehension.[1]

Theory

Research shows that embodiment is present in native language processing,[3] and if embodiment occurs in first language processing, then embodiment might also occur in second language processing.[5] How second language is embodied compared to first language is still a topic of debate. Currently, there are no known theories or models that address the presence or absence of embodiment in second language processing, but there are bilingual processing models that can lead to multiple hypotheses of embodiment effects in second language learning.[6]

Revised Hierarchical Model (RHM)

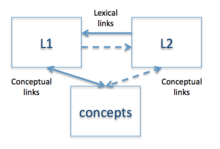

The Revised Hierarchical Model (RHM) hypothesizes that lexical connections are stronger from L2 to L1 than from L1 to L2. In other words, translating a word from second language to first language occurs faster than vice versa.[7] However, while translating from native language to second language might be delayed, the semantics, or word meanings of the information being conveyed, are maintained and understood by the translator.

What this means in terms of embodied bilingual language is that there should be no difference in embodiment effects between first language processing and second language processing. Because the RHM model posits that semantic representations are shared across languages, meanings found in first language action, perception, and emotion will transfer equally into second language processing[6]

Extended Bilingual Interactive Activation (BIA+) Model

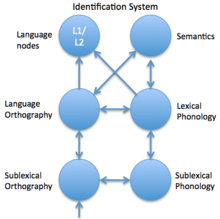

According to the BIA+ Model of bilingual lexical processing, the brain activates both languages when recognizing a word in either language. Rather than selecting a single language, lexical access, or the sound-meaning connections of a language, is non-selective across languages. The BIA+ model suggests that orthographic representations activate first, followed by their associated phonological and semantic representations. The speeds of these activations depend on frequency of use of the language. Given this proposition, if second language is used less often than first language, second language activation occurs more slowly than first language activation. However, the BIA+ model argues that these differences in activation time are minuscule.[8]

Similar to the RHM, the BIA+ model says that while there are slight differences in time when accessing word meanings in both first and second languages, the semantic representations are maintained. Thus, in terms of embodiment, the BIA+ model would suggest that embodiment effects, too, are maintained across native and second language processing.[6]

Sense Model

The Sense Model takes a different position from the previously stated models. The Sense Model supposes that native language words are associated with a greater number of semantic senses than second language words and argues for partially overlapping distributed semantic representations for L1 and L2 words. As a result, the Sense Model argues that semantic representations in second language are “less rich” than in those in the native language.[9] If this is the case in embodied bilingual language, then embodiment in second language processing may be minimal or even completely lacking.[6]

Action

Non-Selective Motor Systems

Embodied bilingual processing is rooted in motor processing because research shows that the motor cortex activates during language processing. In first language processing, for example, leg-related words like “kick” and “run” stimulate the part of the motor cortex that controls leg motions.[10] This illustrates that language describing motor actions activates motor systems in the brain, but only when the words provide literal meaning as opposed to figurative meaning.[11] Following L1 embodiment, L2 embodiment assumes that the words “punch” and “throw” in a second language will also stimulate the same parts of the motor cortex as does first language words.[1] In essence, language that describes motor actions activates motor systems in the brain.[1] If this holds true for all languages, then the processing that occurs when understanding and using a second language must also activate motor regions of the brain, just as native language processing does.

Research shows that both first and second language action words rely on the motor cortex for language processing, strengthening the claim that the motor cortex is necessary for action language processing.[5] This research suggests that action language processing has direct access to semantic motor representations in both languages.[6] This results from second language motor systems calling on and activating information from first language motor systems. Initially, the semantic representations stimulated by the first language are stronger than that of the second language. But with more experience and exposure to the second language, sensorimotor involvement and second language comprehension becomes stronger.[10] The more often a second language is used, the stronger the neural networks and associations become, and thus some researchers argue that semantic representations in second language become just as prominent as for first language.[12]

Perception

Grounded or embodied cognition is a theoretical view that assumes knowledge is represented in the mind as modal representations, which are memories of perceptual, motor, and affective experiences.[2] Perceptual features include orientation, location, visibility conditions, motion, movement direction, and action direction. All of these perceptual features are necessary for comprehending language. If this is true for first language processing, then this must also be true for second language processing.[11]

These perceptual features occur when imagining an action, recalling an action, and observing various sensory information.[6] In addition to motor brain areas, somatosensory areas, which deal with touch and physical awareness, are also activated. This sensory information contributes to formulating the mental simulation, or imagination of the action being described, that necessitates language comprehension[11]

Finally, research shows that embodied bilingual language processing not only activates the perceptual simulation of first and second language meanings, but this activation is automatic.[5] Second language users automatically stimulate word meanings in a detailed perceptual fashion. Rather than consciously using strategies for language comprehension, bilinguals automatically perceive and construct meaning.

Emotion

Embodied bilingual language also assumes that comprehension of language activates parts of the brain that correspond with emotion. Research provides evidence that emotion words are embedded in a rich semantic network.[13] Given this information, emotion is better perceived in a first language because linguistic development coincides with conceptual development and development of emotional regulation systems. Linguistic conditioning spreads to phonologically and semantically related words of the same language, but not to translation equivalents of another language.

Disembodied Bilingual Language and Emotion

Some researchers have argued for disembodied cognition when it comes to processing emotion. The idea of disembodied cognition comes from research, which shows that less emotion is shown by a bilingual person when using a second language. This may illustrate that less emotionality is attached to second language, which then leads to the reduction of biases such as decision bias or framing bias.[14] One study examining the anxiety effects of L2 words such as “death” found that those with lower levels of proficiency in L2 were more likely than L1 speakers to experience feelings of anxiety.[15] Because the emotion is less interpreted during second language processing, speakers will be more likely to ignore or fail to comprehend the emotion of a situation when making decisions or analyzing situations.

The theory of disembodied cognition posits that because emotions are not as clearly recognized in a second language versus a first language, emotions will not affect and bias a person who is using a second language as much as using a first language. This lack of comprehension of emotion provides evidence for the Sense Model, which hypothesizes that embodied cognition fails to be present in second language processing.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vukovic, Nikola; Shtyrov, Yury (2014). "Cortical motor systems are involved in second-language comprehension: Evidence from rapid mu-rhythm desynchronisation". NeuroImage 102: 695–703. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.039.

- 1 2 3 Barsalou, Lawrence (1999). "Perceptual symbol systems". Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22 (44): 577–660. doi:10.1017/S0140525X99002149.

- 1 2 Bergen, Benjamin; Lau, Ting-Ting Chan; Narayan, Schweta; Stojanovic, Diana; Wheeler, Kathryn (2010). "Body part representations in verbal semantics". Memory and Cognition 38 (7): 969–981. doi:10.3758/MC.38.7.969.

- ↑ Glenberg, Arthur (2002). "Grounding language in action". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 9 (3): 558–565. doi:10.3758/BF03196313.

- 1 2 3 Vukovic, N; Williams, J (2014). "Automatic perceptual simulation of first language meanings during second language sentence processing in bilinguals". Acta Psychologica 145: 98–103. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.11.002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 De Grawe, S; Willems, R.M.; Rueschemeyer, S; Lemhöfer, K; Schriefers, H (2014). "Embodied language in first- and second-language speakers: Neural correlates of processing motor verbs.". Neuropsychologia 56: 334–349. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.02.003.

- ↑ Kroll, Judith; Stewart, Erika (1994). "Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connection between bilingual memory representations.". Journal of Memory and Language 33 (2): 149–174. doi:10.1006/jmla.1994.1008.

- ↑ Dijkstra, Tom; Van Heuven, Walter (2002). "The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision". Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 5 (3): 175–197. doi:10.1017/S1366728902003012.

- ↑ Finkbeiner, Matthew; Forster, Kenneth; Nicol, Janet; Nakamura, Kumiko (2004). "The role of polysemy in masked semantic and translation priming". Journal of Memory and Language 51: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2004.01.004.

- 1 2 Pulvermüller, F; Härle, M; Hummel, F (2001). "Walking or Talking?: Behavioral and Neurophysiological Correlates of Action Verb Processing". Brain and Language 78 (2): 143–168. doi:10.1006/brln.2000.2390.

- 1 2 3 Bergen, Benjamin; Wheeler, Kathlyn (2010). "Grammatical aspect and mental simulation.". Brain and Language 112: 150–158. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2009.07.002.

- ↑ Dudschig, C; Kaup, B (2013). "Embodiment and second-language: Automatic activation of motor responses during processing spatially associated L2 words and emotion L2 words in a vertical stroop paradigm.". Embodiment and second-language: Automatic activation of motor responses during processing spatially associated L2 words and emotion L2 words in a vertical stroop paradigm. 132: 14–21. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2014.02.002.

- ↑ Pavlenko, A (2008). "Emotion and emotion-laden words in the bilingual lexicon". Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 11: 147–165. doi:10.1017/S1366728908003283.

- ↑ Pavlenko, A (2012). "Affective processing in bilingual speakers: Disembodied cognition?". International Journal of Psychology 47 (6): 405–428. doi:10.1080/00207594.2012.743665.

- ↑ Keysar, B; Hayakawa, S; An, S (2012). "The foreignlanguage effect: Thinking in a foreign tongue reduces decision biases.". Psychological Science 23: 661–668. doi:10.1177/0956797611432178.