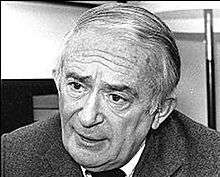

Elmyr de Hory

Elmyr de Hory (born Elemér Albert Hoffmann; Budapest, April 14, 1906 - Ibiza, December 11, 1976) was a Hungarian-born painter and art forger who is said to have sold over a thousand forgeries to reputable art galleries all over the world. His forgeries garnered much celebrity from a Clifford Irving book, Fake, (1969) F for Fake (1974), a documentary essay film by Orson Welles, and "The Forger's Apprentice: Life with the World's Most Notorious Artist" (2012) by Mark Forgy.

Early life

Most of the information regarding de Hory's early life comes from what he told American writer Clifford Irving, who wrote the first biography about him. Since Elmyr's success was reliant upon his skills of deception and invention, it would be difficult to take the facts that he told about his own life at face value, as Clifford Irving himself admitted. Elmyr claimed that he was born into an aristocratic family, that his father was an Austro-Hungarian ambassador and that his mother came from a family of bankers. However, subsequent investigation has suggested that Elmyr's childhood was, more likely, of an ordinary, middle class variety.

Research done in 2011 by Mark Forgy, Colette Loll, Dr. Jeff Taylor, and Andrea Megyes dispelled some of the longstanding myths surrounding Elmyr, most notably definitively establishing his true identity from marriage and birth records at the Association of Jewish Communities in Budapest. He was born Elemér Albert Hoffmann on April 14, 1906. Both his parents were Jewish. His father's occupation was listed as "Wholesaler of handcrafted goods." His parents did not divorce when Elmyr was sixteen as he asserted in the Clifford Irving biography. An updated account of de Hory's life appears in Mark Forgy's memoir, The Forger's Apprentice: Life with the World's Most Notorious Artist.

At the age of 16, he began his formal art training in the Hungarian art colony of Nagybánya (now in Romania). At 18, he joined the Akademie Heinmann art school in Munich, Germany to study classical painting. In 1926 he moved to Paris, and enrolled in the Académie la Grande Chaumière, where he studied under Fernand Léger. By the time he concluded his traditional education in Paris in 1928, the focus of his studies in figurative art had been eclipsed by fauvism, expressionism, cubism and other nontraditional movements, all of which made Elmyr's art appear passé, out of step with new trends and public tastes. This harsh reality and the economic shock waves of the Great Depression dimmed any prospects of his making a living from his art. New evidence (Geneva Police records) indicates charges and arrests for minor crimes during the late 1920s and 30s.

(*These next two paragraphs relay de Hory's own account, though, at this time, there is no historical evidence to confirm or deny their accuracy.) He returned to Hungary at the outbreak of the Second World War. Shortly after, he became involved with a British journalist and suspected spy. This friendship landed him in a Transylvanian prison for political dissidents in the Carpathian Mountains. During this time, de Hory befriended the prison camp officer by painting his portrait. Later, during the Second World War, de Hory was released.

Within a year, Elmyr de Hory was back in jail, this time imprisoned in a German concentration camp for being both a Jew and a homosexual. (While his homosexuality was proven over time, investigation into his past has shown the likelihood that Elmyr was at one time christened as a Calvinist. Such an ostensible conversion did not stop the Nazi government from targeting people who were born Jewish for extermination). He was severely beaten and was transferred to a Berlin prison hospital, from which he escaped. He returned to Hungary, and it was there, he said, that he learned that his parents had been killed and their estate confiscated. (However, according to Mark Forgy's account, both de Hory's mother and brother were listed as holocaust survivors.)

Life as a forger

On arriving in Paris after the war, de Hory attempted to make an honest living as an artist, but soon discovered that he had an uncanny ability to copy the styles of noted painters. In 1946, he sold a pen and ink drawing to a British woman who mistook it for an original work by Picasso. His financial desperation trumped his scruples, as was most often the case for the next two decades. To his mind, it offered redemption from the starving artist scenario, buttressed by the comfortable rationalization that his buyers were getting something beautiful at "friendly" prices. He began to sell his Picasso pastiches to art galleries around Paris, claiming that he was a displaced Hungarian aristocrat and his offerings were what remained from his family's art collection, or that he had acquired them directly from the artist whom he had known during his years in Paris.

That same year Elmyr de Hory formed a partnership with Jacques Chamberlin, who became his art dealer. They toured Europe together selling the forgeries until de Hory discovered that, although they were supposed to share the profits equally, Chamberlin had kept most of the profits. De Hory ended the relationship and resumed selling his fakes on his own. After a successful sale of drawings in Sweden, he bought a one-way ticket for Rio de Janeiro in 1947. There, living from the sales of his fakes, he resumed creating his own art, though, the sales of his portraits, landscapes, or still lifes in his own avant-garde style did not bring in the kind of money he had become accustomed to from his newly created master works. In August of 1947 he visited the United States on a three-month visa and decided to stay there, moving between New York City, Los Angeles, Miami, and Chicago for the next twelve years. Elmyr expanded his forgeries to include works in the manner of Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani and Renoir. His uninterrupted success came to a halt in Boston after he sold one of his "Matisse" drawings to the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University in the mid-1950s. Shortly after its sale, he offered a "Modigliani" and a "Renoir" drawing from his collection. An alert curator noticed a stylistic similarity among the three drawings and refused to buy his subsequent offerings. She then began contacting other institutions and galleries, asking if they knew or had purchased artworks from the debonair E. Raynal. The American art network was now aware of the suave collector and seller of dubious works by modern masters. Because some of the galleries Elmyr de Hory had sold his forgeries to were becoming suspicious, he began to use pseudonyms, and to sell his work by mail order. Some of de Hory's many pseudonyms included Louis Cassou, Joseph Dory, Joseph Dory-Boutin, Elmyr Herzog, Elmyr Hoffman and E. Raynal.

Making a business of forgery

In 1955 Elmyr de Hory sold several forgeries to Chicago art dealer, Joseph W. Faulkner, who later discovered they were fakes. Faulkner pressed charges against Elmyr de Hory and initiated a federal lawsuit against him, alleging mail and telephone fraud. Elmyr later moved to Mexico City, where he was briefly detained and questioned by the police, not for his artistic endeavors, but regarding his connection to a suspect in the murder of a British man, whom Elmyr claimed he had never met. When the Mexican police attempted to extort money from him, Elmyr hired a lawyer who also attempted to extort money from him, by charging exorbitant legal fees. Elmyr paid the lawyer with one of his forgeries and returned to the USA.

On his return, Elmyr de Hory discovered that his paintings were fetching high prices at several art galleries, and was incensed that the galleries had only paid him a fraction of what they thought the paintings were worth. Further compounding de Hory's plight was that the manner of his forgeries had become recognizable, and now a person of interest to the FBI. This unwanted attention may have prompted de Hory to temporarily abandon his fakery and resume creating his own artwork once more. This led him to an ascetic existence in a low-rent apartment near Pershing Square in Los Angeles. Here, he had limited success, mostly selling paintings of pink poodles to interior decorators. However, his self-imposed exile was not to his liking. He decided to return to the East Coast and try his luck once more at his illicit craft, for which he always found an eager buyer - eventually. In Washington DC, Elmyr began an ill-fated association with a picture dealer that ended in disaster. In 1959, suffering from depression, he attempted suicide by overdose of sleeping pills. A friend rescued him and called an ambulance. His stomach was pumped, and after a stay in the hospital, de Hory convalesced in New York City, helped by an enterprising young man, Fernand Legros.

Legros accompanied Elmyr de Hory back to Miami where he continued to regain his health. When he imprudently took Legros into his confidence, the other man quickly recognized an opportunity and importuned the artist to let him sell his work in exchange for a 40% cut of the profits, with Legros assuming all the risks inherent in the sale of forgeries. With Legros, de Hory again toured the United States. In time, Legros demanded his cut be increased to 50%, when, in reality, Legros was already keeping much of the profit. On one of these trips Legros met Réal Lessard, a French-Canadian, who later became his lover. The two had a volatile relationship, and in late 1959 Elmyr de Hory decided to leave the two and return to Europe.

In Paris, Elmyr de Hory unexpectedly ran into Legros. Elmyr revealed to him that some of his forgeries were still back in New York. Legros devised a plan to steal the paintings and sell them, making a name for himself and his art gallery in the process. Later that year, Legros persuaded de Hory to resume their partnership. Legros and Lessard would continue to sell de Hory's work, and agreed to pay him a flat fee of $400 a month, enough to guarantee Elmyr a comfortable and risk-free life in his newfound home, the Spanish Mediterranean island of Ibiza.

Elmyr de Hory always denied that he had ever signed any of his forgeries with the name of the artist whom he was imitating. This is an important legal matter, since painting in the style of an artist is not a crime - only signing a painting with another artist's name makes it a forgery. This may be true, as Legros may have signed the paintings with the false names.

Unmasking the forger

In 1964, now 58 years old, Elmyr de Hory began to tire of the forgery business, and soon his work began to suffer. Consequently, many art experts began noticing that the paintings they were receiving were forgeries. Some of the galleries examining de Hory's work alerted Interpol, and the police were soon on the trail of Legros and Lessard. Legros sent de Hory to Australia for a year, to keep him out of the eye of the investigation.

By 1966, more of de Hory's paintings were being revealed as forgeries; one man in particular, Texas oil magnate Algur H. Meadows, to whom Legros had sold 56 forged paintings, was so outraged to learn that most of his collection was forged, that he demanded the arrest and prosecution of Legros. Angered, Legros decided to hide from the police at de Hory's house on Ibiza, where he asserted ownership, and threatened to evict Elmyr. Coupled with this and with Legros' increasingly violent mood swings, Elmyr de Hory decided to leave Ibiza. Legros and Lessard were apprehended soon thereafter, imprisoned on charges of check fraud.

Elmyr continued to elude the police for some time, but, tired of life in exile, decided to move back to Ibiza to accept his fate. In August 1968, a Spanish court convicted him of the crimes of homosexuality, showing no visible means of support, and of consorting with criminals (Legros), sentencing him to 2 months in prison in Ibiza. He was never directly charged with forgery, because the court could not prove that he had ever created any forgeries on Spanish soil. He was released in October 1968 and expelled from Ibiza for one year. During that time he resided in Torremolinos, Spain.

One year following his release Elmyr de Hory, by then a celebrity, returned to Ibiza. He told his story to Clifford Irving who wrote the biography: Fake! The Story of Elmyr de Hory the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time. De Hory appeared in several television interviews, and was featured with Irving in the Orson Welles documentary, F for Fake (1974). In Welles's film, Elmyr de Hory questioned what it was that made his forgeries inferior to the actual paintings created by the artists he imitated, particularly since they had fooled so many experts, and were always appreciated when it was believed that they were genuine. In F for Fake, Welles also poses questions about the nature of the creative process, how trickery, illusion, and duplicity often prevail in the art world, and thus, in some respects, downplays the culpability of the art forger de Hory and outliers like him.

Death

During the early 1970s, Elmyr de Hory again decided to try his hand at painting, hoping to exploit his new-found fame: this time, he would sell his own, original work. While he had gained some recognition in the art world he made little profit, and he soon learned that French authorities were attempting to extradite him to stand trial on fraud charges. This took quite some time, as Spain and France had no extradition treaty at that time.

On December 11, 1976, de Hory's live-in bodyguard and companion, Mark Forgy, informed him that the Spanish government had agreed to extradite Elmyr to France. Shortly thereafter Elmyr de Hory took an overdose of sleeping pills, and asked Forgy to accept his decision, not to intervene or prevent him from taking his life. However, Forgy later went for help to bring de Hory to a local hospital, though, en route, died in Forgy's arms. Clifford Irving has expressed doubts about de Hory's death, claiming that he may have faked his own suicide in order to escape extradition, but Forgy has dismissed this theory.

Legacy

While de Hory’s self-invention was a purposeful intent to deceive, the absence of historical evidence throughout much of his saga invites suspicion of this enigmatic man. There is no verifiable record of his whereabouts during those years between 1940 and 1945 that confirm or deny his account of prison camp internment by the Nazis or the Russians as he claimed in Clifford Irving’s 1969 biography, Fake. Stories about the lives and fate of immediate family members have been debunked. What further confuses de Hory’s fictional universe is the recent research that has corroborated many of his claims. For example, one eye-witness, Charles Gee, has emerged. He rescued de Hory from his first suicide attempt in Washington DC, confirmed his longstanding friendship with Hungarian actress-celebrity, Zsa Zsa Gabor (an association she allegedly denied according to Clifford Irving), de Hory’s story about his New York encounter with Salvador Dalí, among others.

Despite many newfound facts, the repository of information entwining fiction, fantastic-but-true reality, and the spaciousness of uncertainty, continues to aid the legend de Hory constructed around his life. There is no denying his lifetime of friendships with actors, writers, artists, rich and famous people who gravitated to him; here is where we find clues and better understanding of who de Hory was.

De Hory’s friend, secretary, and heir, may give the most accurate and up-close perspective of him (see The Forger’s Apprentice: Life with the World’s Most Notorious Artist by Mark Forgy 2013). It was, by Forgy’s account, de Hory’s charisma that drew friends and converts to the artist/conman. This trait, alloyed with his artistic talent secured sales of his pastiches of the modern masters in an era when success was often the product of personal chemistry over a rigorous scientific analysis of his would-be masterpieces. Herein is a difference between de Hory, his illicit career, and those forgers and fakers who followed him. The scandal in the wake of de Hory’s outing as the ‘greatest forger of the twentieth century,’ yielded some counterintuitive side effects.

First, rather than succumbing to the foreseeable consequences of his criminality, de Hory became something of a folk hero in the anti-establishment atmosphere that pervaded the late 1960s, an age of rebellion and social unrest. Secondly, his ensuing notoriety, he thought, would finally afford him the lifelong recognition he sought, to be seen as a fine artist in his own right. He was wrong. De Hory often referred to himself as “famously infamous,” and he enjoyed his time in the spotlight as a bad-boy media darling, though, that attention never translated into a demand for artwork in his own avant-garde style. It was a bitter but real irony for him for the rest of his life. Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, rather than learning from the mistakes made by art dealers, and collectors, de Hory’s target audience, the commerce of art remains little changed from the halcyon days of his midcentury fakery. The degree of complicity de Hory enjoyed with art dealers is open to speculation, though, even today, art sellers face no fallout from unlawful dealings unless it can be proven that they are ‘knowingly’ complicit in fraudulent transactions (see Knoedler Gallery scandal). Plausible deniability is a commonly used defense to deflect accountability. Furthermore, auction houses distance themselves in issues of provenance or authorship as they are not in the business of ascribing authenticity. (See the standard wordage explaining terms and conditions of sale for Christie’s or Sotheby’s, for example.) These loopholes that allowed many of de Hory’s fakes to fast track to public institutions and private collections are the same pathways that facilitate present-day forgers and fakers.

Forged de Hory forgeries

De Hory’s dubious distinction as an accomplished forger gave him the fame and name recognition he long desired. One offshoot of his notoriety he never anticipated was the wealth of fake “Elmyrs” that has flooded the marketplace since his death in 1976, demonstrating the relentless resourcefulness of fraudsters and the inherent irony of this largely undetected scam. It is unsurprising that de Hory’s odyssey is used as a template by fellow art criminals. What he and they have had in common is alacrity to exploit opportunism and profiteering a mostly unregulated art market affords on both sides of the legal divide.

DE HORY’S SELF-IMAGE

What we are left with is an incomplete picture of de Hory, a complex but secretive man unable to shed his outlaw image, an adept role player, charismatic as many con-men tend to be, and whose notions of morality conformed to the exigencies (being a refugee, stateless, and subject to the vagaries of an artist’s life) he believed threatened his survival. De Hory expressed regret for his illicit career, taking advantage of others, though his rationalizations assuaged his sense of guilt, characterizing his criminality as an optionless necessity, survival by the only means he knew – his artistic skill. He famously asked, “Who would prefer a bad original to a good fake?” It is a question that goes beyond taking ownership of his law-breaking past. His underlying implication is a broader. Whenever authorship or authenticity of an artwork is in question, that reevaluation process forces us to reexamine how we define art, and by extension, our values as a society – an unintended result of their crimes that keeps us honest.

Mark Jones of the British Museum said, “It is the misfortune of fakes that they are almost always defined by what they are not, instead of being valued for what they are.” De Hory would likely agree.

In popular culture

- Intent to Deceive - Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World (2014 - 2015) an exhibition including works by Elmyr de Hory, curated by Colette Loll.

- The Forger's Apprentice - The Musical -(2015) written by Mark Forgy, Kevin Bowen, and C. S. McNerlin.

- The Forger's Apprentice - (2013) written by Mark Forgy and Kevin Bowen. Performed at the 2013 Minnesota Fringe Festival.

- An Unidentified Man - (2011) a one-man play written and performed by Pierre Brault about de Hory.

- National Public Radio - USA (2014) Snap Judgment, interview with Mark Forgy. Podcast available at: snapjudgment.org/elmyr

- Orson Welles' documentary F for Fake (French: Vérités et mensonges) concerns Elmyr de Hory

- A restaurant in Atlanta's Little Five Points is named Elmyr for him and its walls are covered in fakes of famous paintings.

- The song No More Heroes, by British punk rock band The Stranglers, mentions de Hory in the line, "whatever happened to the Great Elmyr(a)?",[1] but it is unclear if this is an error, an intentional feminization, or "Elmyr" with a separate exclamation after.

- A character based on Hory appears in the incomplete final Tintin story Tintin and Alph-Art.

- Hory is also mentioned in Dale Basye's Fibble: where the lying kids go, the fourth in the series.

- In Fate/Strange Fake, the Caster servant, whose ability entails modifying and recreating legends, states that if you wanted someone to recreate legends without limit, you would have to call Elmyr de Hory.

References

- ↑ "Greeting the 500". typepad.com.

- Irving, Clifford (1969). Fake: the story of Elmyr de Hory: the greatest art forger of our time. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- . ONT. 10 October 1991. ISBN 978-0-9517846-0-0 http://books.google.com/books?id=5zR8QgAACAAJ. Retrieved 9 October 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Almost True: The Noble Art of Forgery, 1997 Norwegian documentary film - Knut W. Jorfald, director. Available as an extra on the F for Fake Criterion Collection DVD release.

- Faking It: Elmyr de Hory - The Century's Greatest Art Forger at the Crime Library

- Master (Con) Artist-Painting forger Elmyr de Hory's copies are like the real thing. San Francisco Chronicle. July 29, 1999. Details reports of current forgeries of de Hory works. Jeff Oppenheim, Producer (2011) "Chasing Elmyr" Documentary

External links

- Official website (maintained by de Hory's heir and bodyguard, Mark Forgy)

- Template:Museum of Art Fakes (Exhibition of works by Elmyr de Hory)

|