Ellis Credle

| Ellis Credle | |

|---|---|

|

Ellis Credle | |

| Born |

August 18, 1902 Hyde County on Pamlico Sound, North Carolina, United States |

| Died |

February 21, 1998 Chicago, Illinois |

| Occupation | Writer and Illustrator |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Louisburg College |

| Genre | fiction |

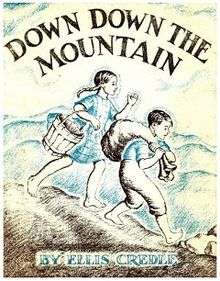

| Notable works | Down Down the Mountain |

| Spouse | Charles de Kay Townsend |

| Children | Richard Fraser Townsend |

Ellis Credle (1902–1998) was the author of a number of books for children and young adults, some of which she also illustrated.[1] Credle (which is pronounced "cradle") is best known as the creator of the acclaimed children's book Down Down the Mountain (1934) and other stories set in the South. While the most successful of her work has been called inspirational, some other stories were controversial for her depiction of African Americans.

Credle was raised in North Carolina, but broke into writing after years of struggle in New York City. She spent the last half of her long life residing in Mexico, where some of her later stories are set. Over the course of her career she had the opportunity to collaborate with her husband, who was a professional photographer, and with her son, who in time became a well-known archeologist.

Biography

Early path

In North Carolina

Born and raised in what she called "the somber low country of North Carolina"[2] in Hyde County on Pamlico Sound, Ellis Credle was the daughter of Zach and Bessie (Cooper) Credle.[3] Her father was a soy bean planter. She said that although her home was far from any railroad and isolated by swamps and forests, she perceived herself at the time as being "right in the middle of things." Her childhood also included time spent on her grandfather's tobacco plantation; on North Carolina's coastal islands; and in the Appalachian Highlands. As an author, she later drew upon her early experiences in these regions when designing her characters and settings.[2][4]

At the age of sixteen, she was admitted to Louisburg College, the same school her grandmother had attended during the Civil War. There she became editor-in-chief of the school literary magazine, "The Collegian". After graduating in 1922 she went to the Blue Ridge Mountains to teach history and French at the Forest City High School.[5] She taught for two years. Unfortunately, she was very unhappy in this work, finding the country "majestic" but the work "uncongenial."[2]

In New York City

Within a short span of time, young Credle pursued a few different directions. By 1925 she was studying at the New York School of Interior Decoration; she soon decided that although this was an art, it was too much a business for her. She began taking courses in commercial art at the Art Students League and also attended the Beaux Arts Architectural Institute, but her funds ran low.

Then for eight years, all the while hoping to return to art, Credle held a variety of jobs: salesgirl, librarian, guitarist, soap distributor, "imported" Japanese lampshade painter, and usher at Carnegie Hall.[2] She also worked as a governess to the children of the wealthy. It is said that she conceived the idea of becoming a children's book author while telling stories to her young charges.[6]

Credle said, "If I had to choose the circumstance that was most important in turning me toward a career of writing and illustrating for children, I should say it was the fact that I saw myself running out of money during the year that I had chosen to study art in New York. To piece out of my foundering financial situation I got a job as part-time governess for two children. One of my duties was to read to them from their library of a hundred or more books for children. This gave me a background in the subject, and I soon discovered that the children preferred the stories I made up myself. These were based on things that had happened to me on my grandfather's tobacco plantation and also adventures on the Carolina outer islands. I began to write these tales down with the idea of finding a publisher."[7]

Another source says that Credle, while looking for work as an illustrator, was advised by an editor to consider writing and illustrating children's literature. Credle related that she then went to the New York Public Library "and read every children’s book they had." Deciding that few of these books were really stories, she determined to create a new kind of book for children using the folk tales and legends of North Carolina.[8] She is said to have "concocted fairy tales and garnered rejection slips" before turning her focus to more realistic stories based in her own background.[9] Credle said, "My first five tries at fiction were all rejected."[8]

While looking for a publisher for her stories, Credle was put to work under the W.P.A. She drew reptiles for the American Museum of Natural History and painted a series of murals for the Brooklyn Children's Museum. Fortunately, this employment afforded Credle a full day off each week to pursue her dream of becoming a children's book author.[2][8] A promising idea for a story set in the Blue Ridge Mountains began to take shape, and Credle set to work "writing and rewriting, doing and redoing the pictures."[7]

Career

Breakthrough

Credle brought her well-polished manuscript to Thomas Nelson and Sons of New York. An editor, as Credle recalled, "liked it and said it might interest the Book of the Month Club, who were now adding children’s books to their list. This instant approval was the giddiest experience I had ever had with an editor." Still, Credle said that when she was asked to leave the manuscript for consideration, she headed for the elevator with the work in hand. The editor caught her, and made a firm commitment that closed the deal.[8]

After much perseverance, Credle had finally found her initial and greatest triumph as an author with Down Down the Mountain (1934) which has been called "the first picturebook ever done of the Blue Ridge country".[6] With dialog presented in an engaging and authentic Southern vernacular, it tells the story of a poor brother and sister who raise turnips, intending to sell the crop to fund the purchase of needed shoes. Along the way down the mountain to town they give turnips away to people who ask, leaving them only one. In the end, the siblings are rewarded serendipitously.

Down Down The Mountain was an overnight and enduring success. It has sold more than 4,000,000 copies. Fifteen editions were published in English between 1934 and 1973 and it is now held by 998 libraries worldwide.[10] In 1947, General Douglas MacArthur asked that the book be translated into Japanese for the children of the occupation.[8] It became a Junior Literary Guild selection, and was in 1971 honored with a Lewis Carroll Shelf Award. Its inclusion in the book Raising Spiritual Children: Cultivating a Revelatory Life attests to the generous spirit of the story.[11]

A contrary view holds the tale to a higher standard of real-world authenticity. Keystone Folklore Quarterly claimed that the story actually "conveys little of the hard life and isolation of the mountaineers." The same source characterizes the children, Hetty and Hank, as "unbelievably optimistic".[12]

Credle was uplifted by her book's acceptance for publication. With great optimism for her future—and the advance royalties in hand—Credle embarked on a cruise to South America. On that momentous journey she met photographer Charles de Kay Townsend. The couple married the following year and afterwards, rather than settling down, they "moved about a great deal".[1][2] Although she changed her name to Ellis Townsend very early in her career, she continued to use her maiden name on all of her subsequent published work.

More success, then a setback

Credle followed up on Down Down The Mountain with three more picture books. The Townsends then went to North Carolina where they collaborated on a photographic story book called The Flop-Eared Hound, which was set on the farm of the author's late father in Hyde County.[5]

Buoyed by continuing success, they next headed out to Blue Ridge country for another photographic story project called Johnny and His Mule. Credle recalled that the book was accepted by a schoolbook publisher, but it was subsequently held for five years without publication. Meanwhile, her previous publisher withheld her royalties on her work in print for two years, claiming she had broken an option clause in her contract. Credle said the result was "financial ruin". In this difficult period, her son Richard was born. Her husband accepted a position at The National Gallery of Art, and the Townsend family moved to Washington, D.C.

Eventually, she was able to retake possession of Johnny and His Mule. The book was finally published, her other royalties were restored to her, and her career continued. But for a time, the setback shook her confidence in the profitability of writing for children.[2]

Controversial content

Some of Credle's early-career stories "ran afoul of the emerging demand for positive portrayals of negro life." Looking back at Across the Cotton Patch (1935)—a story that concerns two white and two black siblings getting into mischief together—Barbara Bader allows that the dialect ascribed to the black children is embarrassing four decades after. She counters, however, that the white children speak a "variant of standard English" as well, and the book nonetheless "comes alive as a picture of American children." She goes on to explain any perceived insensitivity on Credle's part as a product of her time.

Bader's opinion of Credle's next book about an African American child, Little Jeems Henry (1936), was also mixed. She says that the job situation of Jeems Henry's father, portraying a "Wild Man from Borneo" in a circus sideshow, can be perceived in two ways at the reader's discretion: "one can elect to see only degradation... or one can...admire the man's wit and guts."[9] This same story was forcefully condemned in the 2011 volume Raising Racists: The Socialization of White Children in the Jim Crow South. Author Kristina DuRocher faulted Credle for racist caricatures of African Americans, and for reinforcing a stereotype that "without direct white supervision, African Americans could not care for themselves."[13]

Bader surmised that Credle's next book about a black child, The Flop-Eared Hound (1938), demonstrated that author and publisher had bowed to a growing sentiment against these caricature and dialect issues. The book describes the life of a hard-working sharecropper family as they decide whether to keep a young hound who shows up at their cabin. Credle and Townsend presented the story narrated in standard English with extraordinary photographs documenting details of daily life -- washing clothes, getting water from the well, plowing, fishing, gathering persimmons, picking and drying cotton, feeding pigs, cooking, reading the Bible, and riding to church in a buggy. The photography raises the book from a simple children's book to a documentation of African American life in the rural South in the 1930s.

As an illustrator

Ellis Credle's artwork drew a comparison to Thomas Benton's in terms of "the undulating line, the surface agitation," as well as its "restless energy". The artwork in Down Down The Mountain is further praised for an appropriately "rough-hewn, deep-cleft, unfinished quality." The choices of blue and brown for the artwork and of brown again for the printed text are also noted for imparting a cheerful, individual look.[9] The New York Times said in 1934 that Credle's illustrations have "zest and humor and a sympathetic understanding of the mountain country", and the same paper notes in later reviews the "sturdy simplicity" of her work as well as her "easy, fluid style".[14]

Credle has also been credited for the historical accuracy of her drawings. The setting and the attire of characters in Down Down the Mountain, for example, "present authentic material folk culture" of the Appalachian region around the time of the Great Depression. A drawing of the mother making soap while "dressed in the traditional manner" as well as an illustration of the interior of the cabin, supported by a long description, are specifically praised.[12] In Credle's retelling of the folk story Big Fraid, Little Fraid, it is said that her "visual presentation is quite authentic... the log cabin, fireplace, rainbarrel and other objects, not mentioned in the text but extending it, are examples..."[15]

Acclaim was not universal. One unimpressed reviewer wrote of her work on Caleb's Luck, "Credle's illustrations... depict the mountain culture but do not extend or interpret the text. Her illustrations for her own stories are more successful." [16]

As a writer

Even as her career in children's literature flourished, Credle found it difficult to conceive of plots that were fresh enough to satisfy her editors. However, she personally felt children "don't mind if the plot is time-worn [because] their experience doesn't include many plots." She did acknowledge that little children "require well-plotted stories" and will "lose interest if one wanders from the main line and begins dillying and dallying with words."[7] Credle often used the folk tales and legends of North Carolina, as well as her own childhood experiences, to provide a ready framework for her writing.

In the early 1980s, Credle reported that she had two novels in progress: The Mare in the Mist (for young people) and Mist on the Marshes (for adults). She continued to have trouble thinking of plots, and described her method of writing novels as therefore beginning with just setting and characters. As she wrote about what she imagined might happen in the lives of her characters, she would in time discover a logical ending for the story. Credle said that after she had the end in mind, she could then "go back, motivate the people a little more, rearrange the chapters to maintain suspense and lead on to the desired end." Credle herself described this process as "wasteful and time consuming" but mused that it mirrored the way a lot of lives are lived—"on a trial and error method with finally an objective in sight and a rearrangement to get there."[7]

Collaborating with other creators

Although she began her career both writing and drawing her books, Credle collaborated with others a number of times. She illustrated Posey and the Peddler (1938)[17] by Maud Lindsay and Caleb's Luck (Grosset & Dunlap, 1942) by Laura Benét.[18] Tall Tales from the High Hills, and Other Stories (1957), which is summarized as "twenty old tales that have been passed down generation to generation by the mountain folk of the South," was written by Credle, with artwork by Richard Bennett.[19] She also worked with her husband, Charles de Kay Townsend, on books including: Johnny and his Mule; Mexico: Land of Hidden Treasure; and My Pet Peepelo. She wrote, and he provided the photographs. Her son Richard illustrated her Little Pest Pico (T. Nelson, 1969).[20]

Later life

Credle had visited Mexico in the early 1930s and had a positive experience. In 1947, she and her family moved to Guadalajara Mexico, where she and her husband continued to reside for the next thirty-eight years. Although the move was called a retirement, she carried on with writing, often basing stories in Mexico. She never found the level of success she had attained with her tales of the Blue Ridge country. After her husband died, she moved to the shores of Lake Chapala.

"I have never regretted coming to Mexico,” Credle said. “I have always felt happy, at home, and strangely safe here." She returned to the United States on occasion to visit her son in Chicago. She was also invited to the States at times to lecture on North Carolina folklore. At one such meeting held for librarians, she is said to have played guitar and sung songs from her childhood.[8] Ellis Credle was in Chicago at the time of her death, February 21, 1998.

Legacy

Some of her papers are kept in the Special Collections and University Archives of the University of Oregon Libraries. The small "Ellis Credle Papers" collection contains primarily sketches from her books and correspondence with her editors, along with a few handwritten manuscript drafts.[21]

In addition to the enduring popularity of her books, another aspect of Credle's legacy is found in the work of her son, Richard Fraser Townsend. Townsend is an eminent authority on the art, symbolism and archeology of the ancient Americas and several other world cultures. He has acknowledged that the roots of his interest in understanding a new culture and geography reach back to his family's 1947 move to Mexico. Young Richard began exploring with his parents the "monuments and landscapes" of his new home. Ellis Credle delved into Mexico's past and came to write her Mexico, Land of Hidden Treasure (for which Charles Townsend provided the photographs). In time her son became the head of the Department of African Art and Indian Art of the Americas at the Art Institute of Chicago, and author and editor of many books of his own.[8][22]

Partial bibliography

- Down Down the Mountain (1934)

- Across the Cotton Patch (1935)

- Little Jeems Henry (1936)

- Pig-O-Wee (1936)

- Pepe and the Parrot (1937)

- The Flop-Eared Hound (1938)

- That Goat That Went to School (1940)

- Janey's Shoes (1944) - "This hasn't the directness of most of Credle's books, but many children love the might-be-true stories of the past, ... It's a story with a moral -- but not too obviously so"[23]

- Johnny and His Mule (1946)

- My Pet Peepelo (1948) - "Small listeners will like the pictures ... Older children will find the documentary photographs informative and entertaining, with detail which gives them more than usual appeal."[24]

- Here Comes the Showboat (1949) - "This is one of the best books out of the south and dealing with the south that we've had for some time. And one of Ellis Credle's most successful books."[25]

- The adventures of Tittletom (1949) - "It's too bad that there are a number of things about this little story that are not good ... All in all, as you can see, not as satisfactory as her previous books."[26]

- Big Doin's on Razorback Ridge (1956) - "Reminiscent of Ellis Credle's best stories..."[27]

- Tall Tales from the High Hills and Other Stories (1957) - "There is real cracker-barrel gusto to this round up. ... Some are suitable to read aloud to younger children -- others will appeal to older youngsters."[28]

- Big fraid, little fraid : a folktale (1964) - "The simple, slapstick comedy is good for a few hearty laughs. The author's illustrations are unattractive ... Second graders will be able to cope with the large print and easy vocabulary."[29]

- Mexico, Land of Hidden Treasure (1967)

- Monkey See, Monkey Do (1968) - "A thin story otherwise, not much helped by the rather drab black-and-white drawings."[30]

- Little Pest Pico (1969)

- Andy and the Circus (1971)

References

- 1 2 ELLIS CREDLE

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Howard Haycraft (1951). The junior book of authors. Wilson. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Anne Commire (1971). Something about the author: facts and pictures about contemporary authors and illustrators of books for young people. Gale Research. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ "Credle, Ellis" Compton's by Britannica Britannica Online for Kids Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 2013 accessdate=6 March 2013

- 1 2 Miscellaneous Newspaper Articles for Hyde Co., NC (1945) http://www.ncgenweb.us/hyde/news/news1945.HTM

- 1 2 Richard Gaither Walser; North Carolina. State Dept. of Archives and History (1957). Picturebook of Tar Heel authors. State Dept. of Archives and History. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Clare D. Kinsman; Christine Nasso; Gale Research Company (November 1975). Contemporary authors: a bio-bibliographical guide to current authors and their works. Gale Research Co. ISBN 978-0-8103-0027-9. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Ellis Townsend A Literary Treasure" by Shep Lenchek June 1996 http://www.chapala.com/particles/5p.htm

- 1 2 3 Barbara Bader (1976). American picturebooks from Noah's ark to the Beast within. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-708080-3. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ WorldCat Identities http://www.worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n50-17160

- ↑ Patricia Mapes; Greg Mapes (15 August 2009). Raising Spiritual Children: Cultivating a Revelatory Life. Orbital Book Group. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-0-9840767-0-3. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- 1 2 Keystone Folklore Quarterly. Simon Bronner. 1969. p. 151. IND:30000108623129. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ Kristina DuRocher (30 March 2011). Raising Racists: The Socialization of White Children in the Jim Crow South. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3984-5. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Appalachian Children's Literature: An Annotated Bibliography. McFarland. 2010. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7864-6019-9. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Keystone Folklore Quarterly. Simon Bronner. 1969. p. 151. IND:30000108623129. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ↑ Appalachian Children's Literature: An Annotated Bibliography. McFarland. 2010. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7864-6019-9. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ Maud LINDSAY (1938). Posey and the Peddler, Etc. New York, Boston.

- ↑ Laura Benét (1942). Caleb's luck. Grosset & Dunlap. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ Ellis Credle (1957). Tall Tales from the High Hills, and Other Stories. Thomas Nelson. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ Ellis Credle (1969). Little Pest Pico. T. Nelson. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ Guide to the "Ellis Credle Papers, 1964-1971" http://nwda.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv42762

- ↑ Richard F. Townsend (1992). The Ancient Americas: Art from sacred landscapes. Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-86559-104-2. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ "Janey's Shoes". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "My Pet Peepelo". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Here Comes the Showboat". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Adventures of Tittletom". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Big Doin's on Razorback Ridge". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Tall Tales From the High Hills". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Big Fraid, Little Fraid". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Monkey See, Monkey Do". www.kirkusreviews.com. Kirkus Media LLC. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

External links

- Little Jeems Henry (1936) on Internet Archive http://archive.org/stream/littlejeemeshenr00incred#page/n7/mode/2up

- Pepe and the Parrot (1937) on Internet Archive http://archive.org/stream/pepeparrot00cred#page/n7/mode/2up