Elliott Fitch Shepard

| Elliott Fitch Shepard | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

July 25, 1833 Jamestown, New York |

| Died |

March 24, 1893 (aged 59) New York City, New York |

| Cause of death | Pulmonary edema |

| Resting place |

Moravian Cemetery 40°35′03″N 74°07′18″W / 40.584266°N 74.121613°W (initial) |

| Residence | New York City, Briarcliff Manor, New York |

| Ethnicity | English |

| Education | City University of New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt (m. 1868; w. 1893) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

| |

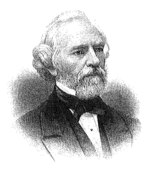

Elliott Fitch Shepard[nb 1] (July 25, 1833 – March 24, 1893) was a New York lawyer, banker, and owner of the Mail and Express newspaper, as well as a founder and president of the New York State Bar Association. Shepard was married to Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt, who was the granddaughter of philanthropist, business magnate, and family patriarch Cornelius Vanderbilt. Shepard's Briarcliff Manor residence Woodlea and the Scarborough Presbyterian Church, which he founded nearby, are contributing properties to the Scarborough Historic District.

Shepard was born in Jamestown, New York, one of three sons of the president of a banknote-engraving company. He attended the City University of New York, and practiced law for about 25 years. During the American Civil War, Shepard was a Union Army recruiter and earned the rank of colonel. He was later a founder and benefactor of several institutions and banks. When Shepard moved to the Briarcliff Manor hamlet of Scarborough-on-Hudson, he founded the Scarborough Presbyterian Church and built Woodlea; the house and its land are now part of Sleepy Hollow Country Club.

Early life

Shepard was born July 25, 1833 in Jamestown in Chautauqua County, New York. He was the second of three sons of Fitch Shepard and Delia Maria Dennis; the others were Burritt Hamilton and Augustus Dennis.[1] Fitch Shepard was president of the National Bank Note Company (later consolidated with the American and Continental Note Companies), and Elliott's brother Augustus became president of the American Bank Note Company.[2] Fitch, son of Noah Shepard, was a descendant of Thomas Shepard (a Puritan minister) and James Fitch (son-in-law of William Bradford). Delia Maria Dennis was a descendant of Robert Dennis, who emigrated from England in 1635.[1] Elliott was described in 1897's Prominent Families of New York as "prominent by birth and ancestry, as well as for his personal qualities".[3] He attended public schools in Jamestown and the college-preparatory University Grammar School (then located in the City University of New York building),[4] and graduated from the university in 1855.[5] Shepard began studying law under Edwards Pierrepont, and was admitted to the bar in the city of Brooklyn in 1858.[6]

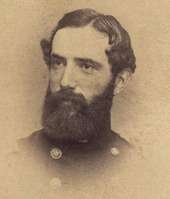

Civil War service

At the outbreak of the American Civil War Shepard became an aide-de-camp to Union Army General Edwin D. Morgan, with the rank of colonel. Shepard never entered the field, but was involved in recruiting volunteers.[5] In 1862 he visited Jamestown to inspect, equip and provide uniforms for the Chautauqua regiment, his first return since age twelve,[1][6] and was welcomed by a group of prominent citizens.[1] Shepard recruited and organized the 51st Regiment, New York Volunteers, which was named the Shepard Rifles in his honor.[7] George W. Whitman, brother of the poet Walt Whitman and a member of the regiment, was notified by Shepard of a promotion; Shepard may have influenced his subsequent promotion to major in 1865. In addition, Shepard was involved in correspondence with Walt Whitman.[8][9]

Shepard was placed in charge of the recruiting station in Elmira, and enlisted 47,000 men from the surrounding area.[2] Although President Abraham Lincoln offered him a promotion to brigadier general, Shepard declined in deference to officers who had seen field service.[6]

Career

In 1864, Shepard was a member of the executive committee and chair of the Committee on Contributions from Without the City for the New York Metropolitan Fair. He chaired lawyers' committees for disaster relief, including those in Portland, Maine and Chicago after the 1866 Great Fire and the 1871 Great Chicago Fire respectively, and was a member of the municipal committee for victims of the 1889 Johnstown Flood.[7]

In 1867 Shepard was presented to Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt at a reception given by Governor Morgan;[5] their difficult courtship[2] was opposed by Margaret's father, William Henry Vanderbilt.[10] A year later, on February 18, 1868, they were married in the Church of the Incarnation in New York City.[5][11] After an 1868 trip to Tarsus, Mersin he helped found Tarsus American College,[12] agreeing to donate $5,000 a year to the school and leave it an endowment of $100,000 ($2.63 million today[13]).[14][15] He became one of the school's trustees and vice president of the board.[4]

In 1868, Shepard became a partner of Judge Theron R. Strong in Strong & Shepard, continuing the business after Strong's death.[6][16] He continued to practice law for the next 25 years;[5] he helped found the New York State Bar Association in 1876, and in 1884 was its fifth president.[17][18] In 1875 Shepard drafted an amendment establishing an arbitration court for the New York Chamber of Commerce, serving on its five-member executive committee the following year.[19] In 1880, the New York City Board of Aldermen appointed Shepard and Ebenezer B. Shafer to revise and codify the city's local ordinances to form the New-York Municipal Code; the last revision was in 1859.[6][20]

During the 1880s he helped found the American Savings Bank, the Bank of the Metropolis and the Columbian National Bank.[21](p154) On March 20, 1888, Shepard purchased the Mail and Express newspaper (founded in 1836, with an estimated value of $200,000 ($5.27 million today[13]) from Cyrus W. Field[6][22] for $425,000 ($11.2 million today[13]).[2][5] Deeply religious, Shepard placed a verse from the Bible at the head of each edition's editorial page. As president of the newspaper company until his death, he approved every important decision or policy.[23] In the same year, Shepard became the controlling stockholder of the Fifth Avenue Stage Company to force it to halt work on Sundays (the Christian Sabbath).[5][24]

When Margaret's father died in 1885, she inherited $12 million ($316 million today[13]).[5] The family lived at 2 West 52nd Street in Manhattan,[25] one of three houses of the Vanderbilt Triple Palace which were built during the 1880s for William Henry Vanderbilt and his two daughters. After Elliott's death Margaret transferred the house to her sister's family, who combined their two houses into one.[26] The houses were eventually demolished; the nine-story De Pinna Building was built there in 1928 and was demolished around 1969.[27] 650 Fifth Avenue is the building currently on the site.

Shepard and his family toured the world from 1884 to 1887,[21](p154) visiting Asia, Africa, Europe and Alaska.[6] He documented a trip from New York to Alaska in The Riva.: New York and Alaska taken by himself, his wife and daughter, six other family members, their maid, a chef, butler, porter and conductor. According to Shepard, the family traveled 14,085 miles (22,668 km) on 26 railroads and stayed at 38 hotels in nearly five months.[28][29] After the 1884 trip, aware of the opportunity for church work in the territory, he founded a mission and maintained it with his wife for about $20,000 ($526,700 today[13]) a year. For some time Shepard worshiped at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church under John Hall,[2] and was a vice president of the Presbyterian Union of New-York.[30] Shepard was president of the American Sabbath Union for five years,[7] and he also served as the chairman of the Special Committee on Sabbath Observance.[31]

Briarcliff Manor developments

During the early 1890s Shepard moved to Scarborough-on-Hudson in present-day Briarcliff Manor,[21](p158) purchasing a Victorian house from J. Butler Wright. He had a mansion (named Woodlea, after Wright's house) built south of the house, facing the Hudson River,[32] and improved its grounds. Construction of the mansion began in 1892,[33] and was completed three years later.[21](p153) Shepard died in 1893, leaving Margaret to oversee its completion.[21](pp159–60) The finished house has between 65,000 and 70,000 square feet (6,000 and 6,500 m2), making it one of the largest privately-owned houses in the United States.[21](p163)[34][35]

After Shepard's death Margaret lived there in the spring and fall,[21](p165) with her visits becoming less frequent. By 1900 she began selling property to Frank A. Vanderlip and William Rockefeller, selling them the house in 1910. Vanderlip and Rockefeller assembled a board of directors to create a country club; they first met at Vanderlip's National City Bank Building office at 55 Wall Street (Vanderlip was president of the bank at the time). Sleepy Hollow Country Club was founded, with Woodlea becoming its clubhouse and the J. Butler Wright house as its golf house.[21](p169)

Shepard established a small chapel on his Briarcliff Manor property, and founded the Scarborough Presbyterian Church in 1892.[36] The church and its manse were donated by Margaret after his death. It was designed by Augustus Haydel (a nephew of Stanford White) and August D. Shepard, Jr. (a nephew of Elliott Shepard and William Rutherford Mead).[21] The church, dedicated on May 11, 1895 in Shepard's memory,[21](p165) was briefly known as Shepard Memorial Church.[37]

Family and personal life

Shepard and Margaret had five daughters and one son: Florence (1869–1869), Maria Louise (1870–1948), Edith (1872–1954), Marguerite (1873–1895), Alice (1874–1950) and Elliott Jr. (1877–1927). The children attended Sunday school and church, and were educated by private tutors and governesses. Shepard also employed a private chef for his family.[38] Shepard was a strict father known to beat his son, who was described as being as wild as his father was rigid and moralizing.[38]

Shepard was tall, with a pleasant expression and manner,[7] and The New York Times called him the "perfect type of well-bred clubman". He had thick hair, manicured nails, a well-trimmed beard and an athletic figure.[21](p154) An opponent of antisemitism, he attended dinners publicizing the plight of Russian Jews and regularly addressed Jewish religious and social organizations avoided by others. He rented pews in many New York churches, supported about a dozen missionaries and was described as a generous donor to hospitals and charitable societies. Shepard was politically ambitious, and decided to build Woodlea as a symbol of power and influence.[21](p157) Shepard had horses and carriages which were ridden by the family in parks, and he prided himself on his equestrianism.[38]

Shepard was a supporter of the Republican Party, contributing $75,000 ($1.98 million today[13]) to the 1888 Presidential campaign fund and $10,000 ($263,400 today[13]) to the state committee for the Fassett campaign. He furnished Shepard Hall, at Sixth Avenue and 57th Street in New York City, offering it rent-free to the Republican Club.[2] Shepard belonged to a number of organizations: the New York State Bar Association, the American Museum of Natural History, the National Academy of Design, the Sons of the American Revolution, the New York Yacht Club, the New York Athletic Club, the New York Press Club, the Lawyers' Club of New York, the Republican Club, the Manhattan Athletic Club, the Riding Club, the Twilight Club, the Union League Club of New York, the New England Society of New York, the Adirondack League and the Union League of Brooklyn.[6]

Later life, death, and legacy

In 1892, the City University of New York gave Shepard a Master of Laws degree and the University of Omaha gave him a Doctor of Laws degree.[39] On January 11, 1893, Shepard addressed the House Committee on the Columbian Exposition in an effort to convince the committee not to open the exposition on a Sunday - the Sabbath.[40] Shepard himself attended, having spent $25,000 ($658 thousand today[13]) on September 7, 1891 in reserving sixteen rooms with board at the Auditorium Hotel for six months during the fair.[41]

Shepard died unexpectedly during the afternoon of March 24, 1893 at his Manhattan residence. Two doctors were attempting to remove a bladder stone from him; they gave him ether at 12:45 p.m. For a few minutes Shepard did not seem to react, though soon afterward his color started changing and his respiration and pulse dimmed, so administration of ether was stopped, however not enough ether was given to continue with the operation. His condition started to worsen again; the doctors suspected food or vomit was blocking his windpipe or bronchial tubes. The doctors then administered oxygen, which helped temporarily; however, at 4:00 p.m. his pulse became steadily more feeble, he fell unconscious, and died at 4:10 p.m. His cause of death was edema and congestion of the lungs, after the administration of ether, but due to an unknown cause.[2][4] Shepard was first buried in the Vanderbilt mausoleum in Moravian Cemetery. On November 17, 1894 one of his daughters, his wife, and her brother George Vanderbilt oversaw the transfer of his remains and those of his daughter Florence to a new Shepard family tomb.[42]

Shepard's estate included the $100,000 Tarsus American College endowment, $850,000 in real estate and $500,000 in personal property for a total of $1.35 million ($35.6 million today[13]). His will distributed money and property to his wife and children, his brother Augustus, and religious organizations.[43] Shepard funded a number of scholarships and prizes, including one at the City University of New York and New York University's annual Elliott F. Shepard Scholarship,[6] and donated a large collection of books from lawyer Aaron J. Vanderpoel's library to the New York University School of Law.[44]

When the wife of Chicago publisher Horace O'Donoghue read him the news of Shepard's death four days after the event, he picked up a razor and slit his throat.[45] Although his suicide was first thought to be impulsive, it was later learned that the likely cause was O'Donoghue's large debts to Chicago publishing houses.[46]

Selected works

- Shepard, Elliott Fitch; Shafer, Ebenezer B. (1881). Ordinances of the Mayor, Aldermen and Commonalty of the City of New York: In Force January 1, 1881. New York, New York. OCLC 680539530.

- Shepard, Elliott Fitch (1886). Labor and Capital are One (10th ed.). New York, New York: American Bank Note Company. OCLC 43539083.

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Young, Andrew W. (1875). History of Chautauqua County. Buffalo, New York: Printing house of Matthews & Warren. p. 370. LCCN 01014073. OCLC 27643135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Elliott F. Shepard Dead". The New York Times. March 25, 1893. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ↑ Weeks, Lyman Horace (1898). Prominent Families of New York. New York, New York: The Historical Company. p. 504. OCLC 4604610.

- 1 2 3 "The Doctors' Statement" (PDF). New-York Tribune 52 (16,934). March 27, 1893. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Illustrated American 13. Chicago, Illinois: The Illustrated American Publishing Company. April 8, 1893. p. 427.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Homans, James E., ed. (1918). The Cyclopedia of American Biography. The Press Association Compilers. pp. 299–300.

- 1 2 3 4 Proceedings of the New York State Bar Association 17. Albany, New York: The New York State Bar Association. 1894. pp. 212–3.

- ↑ "Life & Letters". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Life & Letters". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Death of Col. Elliot F. Shephard". Reading Times. March 25, 1893. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "NYC Marriage & Death Notices 1857–1868". The New York Society Library. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ↑ Page, Walter H., ed. (1908). The World's Work 15. New York, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company. p. 9870. OCLC 1770207.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ↑ Tejirian, Eleanor H.; Simon, Reeva Spector (2012). Conflict, Conquest, and Conversion. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 147–8. ISBN 978-0-231-13864-2.

- ↑ Jernazian, Ephraim K. (1990). Judgement Unto Truth: Witnessing the Armenian Genocide. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4128-2702-7. LCCN 89020662.

- ↑ Ulman, H. Charles (1872). Lawyers' Record and Official Register of the United States. New York, New York: A. S. Barnes & Co. p. 766.

- ↑ "Past Presidents of the New York State Bar Association". New York State Bar Association. 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ Martin, George W. (The Association of the Bar of the City of New York) (1970). Causes and Conflicts: The Centennial History of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, 1870–1970. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 131. ISBN 0-8232-1735-3. LCCN 96053609.

- ↑ Eighteenth Annual Report of the Corporation of the Chamber of Commerce. New York, New York: Press of the Chamber of Commerce. 1876. pp. 41, 171.

- ↑ "Revising the City Ordinances" (PDF). New-York Daily Tribune. July 13, 1878. p. 7. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Foreman, John; Stimson, Robbe Pierce (May 1991). The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations, 1879–1901 (1st ed.). New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 159. ISBN 0-312-05984-1. LCCN 90027083. OCLC 22957281.

- ↑ "His Career as an Editor" (PDF). New-York Tribune. 1893. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ↑ In the Matter of the Application of Alexander B. Larkin for a Writ of Mandamus. Albany, New York: Court of Appeals of the State of New York. 1900. pp. 15, 27. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (October 24, 2014). "Refined in an Era of Superlatives". The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ A Brief History of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church. New York, New York: Stephen Angell. January 1882. p. 57. OCLC 52050563.

- ↑ "Hotel for 57th St. Site". The New York Times. December 22, 1925. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (April 2, 2009). "Queen Anne Meets Plain Jane, a Grand Meat Retailer and a Fifth Avenue 'Ghost'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ Campbell, Robert (2011). In Darkest Alaska: Travel and Empire Along the Inside Passage. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780812201529.

- ↑ Shepard, Elliott F. (1887). The Riva.: New York and Alaska. pp. 1–16. OCLC 27673783.

- ↑ "Col. Shepard's Funeral" (PDF). New-York Tribune. 1893. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. MacCalla & Company, printers. May 22, 1893. p. 54. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ Diedrich, Richard (2007). The 19th Hole: Architecture of the Golf Clubhouse. Mulgrave, Vic.: The Images Publishing Group. pp. 90–5. ISBN 978-1-86470-223-1.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination form – Scarborough Historic District". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Sleepy Hollow Country Club – Scarborough, New York: General Manager" (PDF). Texas Lone Star Chapter of the Club Manager's Association of America. Denehy Club Thinking Partners. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ↑ Finan, Tom. "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow Rides On" (PDF). Club Management (August 2004). Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ↑ Pattison, Robert (1939). A History of Briarcliff Manor. William Rayburn. OCLC 39333547.

- ↑ "The History of Scarborough Presbyterian Church". Scarborough Presbyterian Church. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Crodise, L. F. (February 13, 1891). "Some of Col. Shepard's Good Points". The Epoch (New York, New York: The Epoch Publishing Co.) 9 (210): 21–2. OCLC 31581175.

- ↑ Report of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Dando Printing and Publishing Company. 1893. p. 439.

- ↑ "The Sabbatarians Have Their Innings at Washington". Los Angeles Herald 39 (93). January 12, 1893. p. 2. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ The World's Fair Visitor. Chicago, Illinois: The World's Fair Visitors' Association. 1891. LCCN ca05002163. OL 24962074M. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Elliott F. Shepard's Body Removed". The New York Times. November 18, 1894. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Elliott F. Shepard's Will". The New York Times. April 12, 1893. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ The University of the City of New York: Catalogue and Announcements. The University of the City of New York. 1889. pp. 141–2.

- ↑ "A Publisher Cuts His Throat". The New York Times. March 28, 1893. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Horace O'Donoghue's Suicide". The New York Times. April 19, 1893. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

Further reading

| Library resources about Elliott Fitch Shepard |

| By Elliott Fitch Shepard |

|---|

- Crodise, L. F. (February 13, 1891). "Some of Col. Shepard's Good Points". The Epoch (New York, New York: The Epoch Publishing Co.) 9 (210): 21–2. OCLC 31581175. For details on Elliott Fitch Shepard's average business day and family.

External links

- Letter to Walt Whitman, from The Walt Whitman Archive

- Works by or about Elliott Fitch Shepard at Internet Archive

|