Electrophoretic light scattering

Electrophoretic light scattering is based on dynamic light scattering. The frequency shift or phase shift of an incident laser beam depends on the dispersed particles mobility. In the case of dynamic light scattering, Brownian motion causes particle motion. In the case of electrophoretic light scattering, oscillating electric field performs the same function.

This method is used for measuring electrophoretic mobility and then calculating zeta potential. Instruments to apply the method are commercially available from several manufacturers. The last set of calculations requires information on viscosity and dielectric permittivity of the dispersion medium. Appropriate electrophoresis theory is also required. Sample dilution is often necessary in order to eliminate particle interactions.

Instrumentation of Electrophoretic light scattering

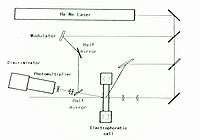

A laser beam passes through the electrophoresis cell, irradiates the particles dispersed in it, and is scattered by the particles. The scattered light is detected by a photo-multiplier after passing through two pinholes. There are two types of optical systems: heterodyne and fringe. Ware and Flygare [1] developed a heterodyne-type ELS instrument, that was the first instrument of this type. In a fringe optics ELS instrument,[2] a laser beam is divided into two beams. Those cross inside the electrophresis cell at a fixed angle to produce a fringe pattern. The scattered light from the particles, which migrates inside the fringe, is amplitude-modulated. The frequency shifts from both types of optics obey the same equations. The observed spectra resemble each other. Oka et al. developed an ELS instrument of heterodyne-type optics[3] that is now available commercially. Its optics is shown in Fig. 3.

A modulator is a translationally moving mirror. A frequency of reference light shifts by the movement. Scattered light from dispersed particle without electrophoretic movement is line broadened. That with electrophoretic movement is line broadened and Doppler shifted. The moving mirror moves to shorten optical pass length, then the frequency shift toward higher frequency.

Heterodyne light scattering

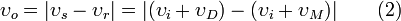

The frequency of light scattered by particles undergoing electrophoresis is shifted by the amount of the Doppler effect,  from that of the incident light, :

from that of the incident light, : .

The shift can be detected by means of heterodyne optics in which the scattering light is mixed with the reference light.

The autocorrelation function of intensity of the mixed light,

.

The shift can be detected by means of heterodyne optics in which the scattering light is mixed with the reference light.

The autocorrelation function of intensity of the mixed light,  , can be approximately described by the following damped cosine function [7].

, can be approximately described by the following damped cosine function [7].

where  is a decay constant and A, B, and C are positive constants dependent on the optical system.

is a decay constant and A, B, and C are positive constants dependent on the optical system.

Damping frequency  is an observed frequency, and is the frequency difference between scattered and reference light.

is an observed frequency, and is the frequency difference between scattered and reference light.

where  is the frequency of scattered light,

is the frequency of scattered light,  the frequency of the reference light,

the frequency of the reference light,

the frequency of incident light (laser light),

and

the frequency of incident light (laser light),

and  the modulation frequency.

the modulation frequency.

The power spectrum of mixed light, namely the Fourier transform of  , gives a couple of Lorenz functions at

, gives a couple of Lorenz functions at  having a half-width of

having a half-width of  at the half maximum.

at the half maximum.

In addition to these two, the last term in equation (1) gives another Lorenz function at

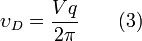

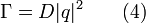

The Doppler shift of frequency and the decay constant are dependent on the geometry of the optical system and are expressed respectively by the equations.

and

where  is velocity of the particles,

is velocity of the particles,  is the amplitude of the scattering vector, and

is the amplitude of the scattering vector, and  is the translational diffusion constant of particles.

is the translational diffusion constant of particles.

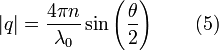

The amplitude of the scattering vector  is given by the equation

is given by the equation

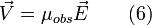

Since velocity  is proportional to the applied electric field,

is proportional to the applied electric field,  , the apparent electrophoretic mobility

, the apparent electrophoretic mobility  is define by the equation

is define by the equation

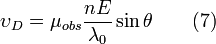

Finally, the relation between the Doppler shift frequency and mobility is given for the case of the optical configuration of Fig. 3 by the equation

where  is the strength of the electric field,

is the strength of the electric field,  the refractive index of the medium,

the refractive index of the medium,  , the wavelength of the incident light in vacuum, and

, the wavelength of the incident light in vacuum, and  the scattering angle.

The sign of

the scattering angle.

The sign of  is a result of vector calculation and depends on the geometry of the optics.

is a result of vector calculation and depends on the geometry of the optics.

The spectral frequency can be obtained according to Eq. (2).

When  , Eq. (2) is modified and expressed as

, Eq. (2) is modified and expressed as

The modulation frequency  can be obtained as the damping frequency without an electric field applied.

can be obtained as the damping frequency without an electric field applied.

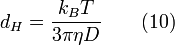

The particle diameter is obtained by assuming that the particle is spherical. This is called the hydrodynamic diameter,  .

.

where  is Boltzmann coefficient,

is Boltzmann coefficient,  is the absolute temperature, and

is the absolute temperature, and  the dynamic viscosity of the surrounding fluid.

the dynamic viscosity of the surrounding fluid.

Profile of Electro-Osmotic Flow

Figure 4 shows two examples of heterodyne autocorrelation functions of scattered light from sodium polystyrene sulfate solution (NaPSS; MW 400,000; 4 mg/mL in 10 mM NaCl). The oscillating correlation function shown by Fig. 4a is a result of interference between the scattered light and the modulated reference light. The beat of Fig. 4b includes additionally the contribution from the frequency changes of light scattered by PSS molecules under an electrical field of 40 V/cm.

Figure 5 shows heterodyne power spectra obtained by Fourier transform of the autocorrelation functions shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 6 shows plots of Doppler shift frequencies measured at various cell depth and electric field strengths, where a sample is the NaPSS solution. These parabolic curves are called profiles of electro-osmotic flow and indicate that the velocity of the particles changed at different depth. The surface potential of the cell wall produces electro-osmotic flow. Since the electrophoresis chamber is a closed system, backward flow is produced at the center of the cell. Then the observed mobility or velocity from Eq. (7) is a result of the combination of osmotic flow and electrophoretic movement.

Electrophoretic mobility analysis has been studied by Mori and Okamoto [16], who have taken into account the effect of electro-osmotic flow at the side wall.

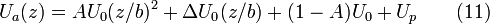

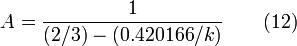

The profile of velocity or mobility at the center of the cell is given approximately by Eq. (11) for the case where k>5.

where

-

cell depth

cell depth -

apparent electrophoretic velocity of particle at position z.

apparent electrophoretic velocity of particle at position z.

-

true electrophoretic velocity of the particles.

true electrophoretic velocity of the particles.

-

thickness of the cell

thickness of the cell

-

average velocity of osmotic flow at upper and lower cell wall.

average velocity of osmotic flow at upper and lower cell wall.

-

difference between velocities of osmotic flow at upper and lower cell wall.

difference between velocities of osmotic flow at upper and lower cell wall.

-

-

, a ratio between two side lengths of the rectangular cross section.

, a ratio between two side lengths of the rectangular cross section.

The parabolic curve of frequency shift caused by electro-osmotic flow shown in Fig. 6 fits with Eq. (11) with application of the least squares method.

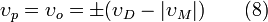

Since the mobility is proportional to a frequency shift of the light scattered by a particle and the migrating velocity of a particle as indicated by Eq. (7), all the velocity, mobility, and frequency shifts are expressed by parabolic equations. Then the true electrophoretic mobility of a particle, the electro-osmotic mobility at the upper and lower cell walls, ware obtained. The frequency shift caused only by the electrophoresis of particles is equal to the apparent mobility at the stationary layer.

The velocity of the electrophoretic migration thus obtained is proportional to the electric field as shown in Fig. 7. The frequency shift increases with increase of the scattering angle as shown in Fig. 8. This result is in agreement with the theoretical Eq. (7).

-

Fig.4 a and b; Correlation function with and without electric field. Sample: NaPSS solution (MW: 400,000) of 4 mg/ml in 10 mM NaCl. Electric field applied: (a) 0 V/cm; (b) 40 V/cm. Scattering angle 7.0 degree, temperature 25 +-0.3

-

Fig. 5. Heterodyne power spectra obtained by FFT of the correlation functions.

-

Fig. 6. Frequency shifts observed at various cell depths.

-

Fig. 7. Electric field dependence of the velocity at the stationary layer.

-

Fig. 8. Frequency shift as a function of scattering angle.

Applications

Electrophoretic Light Scattering (ELS) is primarily used for characterizing the surface charges of colloidal particles like macromolecules or synthetic polymers (ex. polystyrene[4]) in liquid media in an electric field. In addition to information about surface charges, ELS can also measure the particle size of proteins [5] and determine the zeta potential distribution.

Biophysics

ELS is useful for characterizing information about the surface of proteins. Ware and Flygare (1971) demonstrated that electrophoretic techniques can be combined with laser beat spectroscopy in order to simultaneously determine the electrophoretic mobility and diffusion coefficient of bovine serum albumin.[6] The width of a Doppler shifted spectrum of light that is scattered from a solution of macromolecules is proportional to the diffusion coefficient.[7] The Doppler shift is proportional to the electrophoretic mobility of a macromolecule.[8] From studies that have applied this method to poly (L-lysine), ELS is believed to monitor fluctuation mobilities in the presence of solvents with varying salt concentrations.[9] It has also been shown that electrophoretic mobility data can be converted to zeta potential values, which enables the determination of the isoelectric point of proteins and the number of electrokinetic charges on the surface.[10]

Other biological macromolecules that can be analyzed with ELS include polysaccharides. pKa values of chitosans can be calculated from the dependency of electrophoretic mobility values on pH and charge density.[11] Like proteins, the size and zeta potential of chitosans can be determined through ELS.[12]

ELS has also been applied to nucleic acids and viruses. The technique can be extended to measure electrophoretic mobilities of large bacteria molecules at low ionic strengths.[13]

Nanoparticles

ELS has been used to characterize the polydispersity, nanodispersity, and stability of single-walled carbon nanotubes in an aqueous environment with surfactants.[14] The technique can be used in combination with dynamic light scattering to measure these properties of nanotubes in many different solvents.

References

- ↑ R. Ware and W.H. Flygare, J.Colloid Interface Sci. 39: 670 (1972).

- ↑ J. Josefwiicz and F.R. Hallett, Appl. Opt. 14: 740 ( (1975).

- ↑ K. Oka, W. Otani, K. Kameyama, M. Kidai, and T. Takagi, Appl. Theor. Electrophor. 1: 273-278 (1990).

- ↑ Okubo, Tsuneo, and Mitsuhiro Suda. "Absorption of polyelectrolytes on colloidal surfaces as studied by electrophoretic and dynamic light-scattering techniques." Journal of colloid and interface science 213.2 (1999): 565-571.

- ↑ Boeve, E. R., et al. "Zeta potential distribution on calcium oxalate crystal and Tamm-Horsfall protein surface analyzed with Doppler electrophoretic light scattering." The Journal of urology 152.2 Pt 1 (1994): 531-536.

- ↑ Ware BR, Flygare WH. The simultaneous measurement of the electrophoretic mobility and diffusion coefficient in bovine serum albumin solutions by light scattering. Chem Phys Lett. 1971;12(1):81.

- ↑ H.Z. Cummins, N. Knable and Y. Yeh, Phys. Rev. Letters. 12 (1964) 150.

- ↑ W.H. Flygare, The effect of an electric field on the Rayleigh scattered light from a solution of macromolecules, Report No. III, ARPA Contract No. DAHC-15-67-C-0062 to the Materials Research Laboratory, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Wilcoxon, Jess P., and J. Michael Schurr. "Electrophoretic light scattering studies of poly (L‐lysine) in the ordinary and extraordinary phase. Effects of salt, molecular weight, and polyion concentration." The Journal of chemical physics 78.6 (1983): 3354-3364.

- ↑ Jachimska B, Wasilewska M, Adamczyk Z. Characterization of globular protein solutions by dynamic light scattering, electrophoretic mobility, and viscosity measurements. Langmuir. 2008;24(13):6866–72.

- ↑ Strand, Sabina P., et al. "Electrophoretic light scattering studies of chitosans with different degrees of N-acetylation." Biomacromolecules 2.4 (2001): 1310-1314.

- ↑ Jiang, Hu-Lin, et al. "Chitosan-graft-polyethylenimine as a gene carrier." Journal of Controlled Release 117.2 (2007): 273-280.

- ↑ Hartford, S. L., and W. H. Flygare. "Electrophoretic light scattering on calf thymus deoxyribonucleic acid and tobacco mosaic virus." Macromolecules 8.1 (1975): 80-83.

- ↑ Lee, Ji Yeong, et al. "Electrophoretic and dynamic light scattering in evaluating dispersion and size distribution of single-walled carbon nanotubes." Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology 5.7 (2005): 1045-1049.

(1) Surfactant Science Series, Consulting Editor Martin J. Schick Consultant New York, Vol. 76 Electrical Phenomena at Interfaces Second Edition, Fundamentals, Measurements and Applications, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded. Ed by Hiroyuki Ohshima, Kunio Furusawa. 1998. K. Oka and K. Furusawa, Chapter 8 Electrophresis, p. 152 - 223. Marcel Dekker, Inc,

(7) B.R. Ware and D.D. Haas, in Fast Method in Physical Biochemistry and Cell Biology. (R.I. Sha'afi and S.M. Fernandez, Eds), Elsevier, New York, 1983, Chap. 8.

(9) R. Ware and W.H. Flygare, J.Colloid Interface Sci. 39: 670 (1972).

(10) J. Josefwiicz and F.R. Hallett, Appl. Opt. 14: 740 ( (1975).

(11) K. Oka, W. Otani, K. Kameyama, M. Kidai, and T. Takagi, Appl. Theor. Electrophor. 1: 273-278 (1990).

(12) K. Oka, W. Otani, Y. Kubo, Y. Zasu, and M. Akagi, U.S. Patent Appl. 465, 186: Jpn. Patent H7-5227 (1995).

(16) S. Mori and H. Okamoto, Flotation 28: 1 (1980). (in Japanese): Fusen 28(3): 117 (1980).

(17) M. Smoluchowski, in Handbuch der Electrizitat und des Magnetismus. (L. Greatz. Ed). Barth, Leripzig, 1921, pp. 379.

(18) P. White, Phil. Mag. S 7, 23, No. 155 (1937).

(19) S. Komagat, Res. Electrotech. Lab. (Jpn) 348, March 1933.

(20) Y. Fukui, S. Yuu and K. Ushiki, Power Technol. 54: 165 (1988).