Electrophile

In chemistry, an electrophile (literally electron lover) is a reagent attracted to electrons. Electrophiles are positively charged or neutral species having vacant orbitals that are attracted to an electron rich centre. It participates in a chemical reaction by accepting an electron pair in order to bond to a nucleophile. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids (see acid-base reaction theories). Most electrophiles are positively charged, have an atom that carries a partial positive charge, or have an atom that does not have an octet of electrons.

The electrophiles are attacked by the most electron-populated part of one nucleophile. The electrophiles frequently seen in the organic syntheses are cations such as H+ and NO+, polarized neutral molecules such as HCl, alkyl halides, acyl halides, and carbonyl compounds, polarizable neutral molecules such as Cl2 and Br2, oxidizing agents such as organic peracids, chemical species that do not satisfy the octet rule such as carbenes and radicals, and some Lewis acids such as BH3 and DIBAL.

Organic chemistry

Alkenes

Electrophilic addition is one of the three main forms of reaction concerning alkenes.

- Hydrogenation by the addition of hydrogen over the double bond

- Electrophilic addition reactions with halogens and sulfuric acid

- Hydration to form alcohols.

Addition of halogens

These occur between alkenes and electrophiles, often halogens as in halogen addition reactions. Common reactions include use of bromine water to titrate against a sample to deduce the number of double bonds present. For example, ethene + bromine → 1,2-dibromoethane:

- C2H4 + Br2 → BrCH2CH2Br

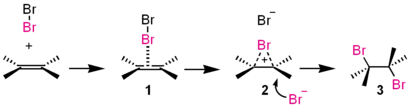

This takes the form of 3 main steps shown below;[1]

- Forming of a π-complex

- The electrophilic Br-Br molecule interacts with electron-rich alkene molecule to form a π-complex 1.

- Forming of a three-membered bromonium ion

- The alkene is working as an electron donor and bromine as an electrophile. The three-membered bromonium ion 2 consisted with two carbon atoms and a bromine atom forms with a release of Br−.

- Attacking of bromide ion

- The bromonium ion is opened by the attack of Br− from the back side. This yields the vicinal dibromide with an antiperiplanar configuration. When other nucleophiles such as water or alcohol are existing, these may attack 2 to give an alcohol or an ether.

This process is called AdE2 mechanism. Iodine (I2), chlorine (Cl2), sulfenyl ion (RS+), mercury cation (Hg2+), and dichlorocarbene (:CCl2) also react through similar pathways. The direct conversion of 1 to 3 will appear when the Br− is large excess in the reaction medium. A β-bromo carbenium ion intermediate may be predominant instead of 3 if the alkene has a cation-stabilizing substituent like phenyl group. There is an example of the isolation of the bromonium ion 2.[2]

Addition of hydrogen halides

Hydrogen halides such as hydrogen chloride (HCl) adds to alkenes to give alkyl halide in hydrohalogenation. For example, the reaction of HCl with ethylene furnishes chloroethane. The reaction proceeds with a cation intermediate, being different from the above halogen addition. An example is shown below:

- Proton (H+) adds (by working as an electrophile) to one of the carbon atoms on the alkene to form cation 1.

- Chloride ion (Cl−) combines with the cation 1 to form the adducts 2 and 3.

In this manner, the stereoselectivity of the product, that is, from which side Cl− will attack relies on the types of alkenes applied and conditions of the reaction. At least, which of the two carbon atoms will be attacked by H+ is usually decided by Markovnikov's rule. Thus, H+ attacks the carbon atom that carries fewer substituents so as the more stabilized carbocation (with the more stabilizing substituents) will form.

This process is called A-SE2 mechanism. Hydrogen fluoride (HF) and hydrogen iodide (HI) react with alkenes in a similar manner, and Markovnikov-type products will be given. Hydrogen bromide (HBr) also takes this pathway, but sometimes a radical process competes and a mixture of isomers may form.

Hydration

One of the more complex hydration reactions utilises sulfuric acid as a catalyst. This reaction occurs in a similar way to the addition reaction but has an extra step in which the OSO3H group is replaced by an OH group, forming an alcohol:

- C2H4 + H2O → C2H5OH

As can be seen, the H2SO4 does take part in the overall reaction, however it remains unchanged so is classified as a catalyst.

This is the reaction in more detail:

- The H–OSO3H molecule has a δ+ charge on the initial H atom. This is attracted to and reacts with the double bond in the same way as before.

- The remaining (negatively charged) −OSO3H ion then attaches to the carbocation, forming ethyl hydrogensulphate (upper way on the above scheme).

- When water (H2O) is added and the mixture heated, ethanol (C2H5OH) is produced. The "spare" hydrogen atom from the water goes into "replacing" the "lost" hydrogen and, thus, reproduces sulfuric acid. Another pathway in which water molecule combines directly to the intermediate carbocation (lower way) is also possible. This pathway become predominant when aqueous sulfuric acid is used.

Overall, this process adds a molecule of water to a molecule of ethene.

This is an important reaction in industry, as it produces ethanol, whose purposes include fuels and starting material for other chemicals.

Electrophilicity scale

| Electrophilicity index | |

| Fluorine | 3.86 |

| Chlorine | 3.67 |

| Bromine | 3.40 |

| Iodine | 3.09 |

| Hypochlorite | 2.52 |

| Sulfur dioxide | 2.01 |

| Carbon disulfide | 1.64 |

| Benzene | 1.45 |

| Sodium | 0.88 |

| Some selected values [3] (no dimensions) | |

Several methods exist to rank electrophiles in order of reactivity [4] and one of them is devised by Robert Parr [3] with the electrophilicity index ω given as:

with  the electronegativity and

the electronegativity and  chemical hardness. This equation is related to classical equation for electrical power:

chemical hardness. This equation is related to classical equation for electrical power:

where  is the resistance (Ohm or Ω) and

is the resistance (Ohm or Ω) and  is voltage. In this sense the electrophilicity index is a kind of electrophilic power. Correlations have been found between electrophilicity of various chemical compounds and reaction rates in biochemical systems and such phenomena as allergic contact dermititis.

is voltage. In this sense the electrophilicity index is a kind of electrophilic power. Correlations have been found between electrophilicity of various chemical compounds and reaction rates in biochemical systems and such phenomena as allergic contact dermititis.

An electrophilicity index also exists for free radicals.[5] Strongly electrophilic radicals such as the halogens react with electron-rich reaction sites, and strongly nucleophilic radicals such as the 2-hydroxypropyl-2-yl and tert-butyl radical react with a preference for electron-poor reaction sites.

Superelectrophiles

Superelectrophiles are defined as cationic electrophilic reagents with greatly enhanced reactivities in the presence of superacids. These compounds were first described by George A. Olah.[6] Superelectrophiles form as a doubly electron deficient superelectrophile by protosolvation of a cationic electrophile. As observed by Olah, a mixture of acetic acid and boron trifluoride is able to remove a hydride ion from isobutane when combined with hydrofluoric acid via the formation of a superacid from BF3 and HF. The responsible reactive intermediate is the CH3CO2H3 dication. Likewise, methane can be nitrated to nitromethane with nitronium tetrafluoroborate NO+

2BF−

4 only in presence of a strong acid like fluorosulfuric acid.

In gitionic (gitonic) superelectrophiles, charged centers are separated by no more than one atom, for example, the protonitronium ion O=N+=O+—H (a protonated nitronium ion). And, in distonic superelectrophiles, they are separated by 2 or more atoms, for example, in the fluorination reagent F-TEDA-BF4[7]

Tetraalkylstannanes

A method was uncovered by Dale E. O'Dell and associates for effecting intramolecular conjugate addition to α-enones of unactiviated carbon nucleophiles which proceeds through the mediation of novel alkyltin(IV) chemistry.

See also

References

- ↑ Lenoir, D.; Chiappe, C. Chem. Eur. J. 2003, 9, 1036.

- ↑ Brown, R. S. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30, 131.

- 1 2 Electrophilicity Index Parr, R. G.; Szentpaly, L. v.; Liu, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc.; (Article); 1999; 121(9); 1922-1924. doi:10.1021/ja983494x

- ↑ Electrophilicity Index Chattaraj, P. K.; Sarkar, U.; Roy, D. R. Chem. Rev.; (Review); 2006; 106(6); 2065-2091. doi:10.1021/cr040109f

- ↑ Electrophilicity and Nucleophilicity Index for Radicals Freija De Vleeschouwer, Veronique Van Speybroeck, Michel Waroquier, Paul Geerlings, and Frank De Proft Org. Lett.; 2007; 9(14) pp 2721 - 2724; (Letter) doi:10.1021/ol071038k

- ↑ Electrophilic reactions at single bonds. XVIII. Indication of protosolvated de facto substituting agents in the reactions of alkanes with acetylium and nitronium ions in superacidic media George A. Olah, Alain Germain, Henry C. Lin, David A. Forsyth J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1975; 97(10); 2928-2929. doi: 10.1021/ja00843a067

- ↑ Knorr Cyclizations and Distonic Superelectrophiles Kiran Kumar Solingapuram Sai, Thomas M. Gilbert, and Douglas A. Klumpp J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9761-9764 doi:10.1021/jo7013092