Free electron model

In solid-state physics, the free electron model is a simple model for the behaviour of valence electrons in a crystal structure of a metallic solid. It was developed principally by Arnold Sommerfeld who combined the classical Drude model with quantum mechanical Fermi–Dirac statistics and hence it is also known as the Drude–Sommerfeld model.

The free electron empty lattice approximation forms the basis of the band structure model known as nearly free electron model. Given its simplicity, it is surprisingly successful in explaining many experimental phenomena, especially

- the Wiedemann–Franz law which relates electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity;

- the temperature dependence of the heat capacity;

- the shape of the electronic density of states;

- the range of binding energy values;

- electrical conductivities;

- thermal electron emission and field electron emission from bulk metals.

Ideas and assumptions

As in the Drude model, valence electrons are assumed to be completely detached from their ions (forming an electron gas). As in an ideal gas, electron-electron interactions are completely neglected. The electrostatic fields in metals are weak because of the screening effect.

The crystal lattice is not explicitly taken into account. A quantum-mechanical justification is given by Bloch's Theorem: an unbound electron moves in a periodic potential as a free electron in vacuum, except for the electron mass m becoming an effective mass m* which may deviate considerably from m (one can even use negative effective mass to describe conduction by electron holes). Effective masses can be derived from band structure computations. While the static lattice does not hinder the motion of the electrons, electrons can be scattered by impurities and by phonons; these two interactions determine electrical and thermal conductivity (superconductivity requires a more refined theory than the free electron model).

According to the Pauli exclusion principle, each phase space element (Δk)3(Δx)3 can be occupied only by two electrons (one per spin quantum number). This restriction of available electron states is taken into account by Fermi–Dirac statistics (see also Fermi gas). Main predictions of the free-electron model are derived by the Sommerfeld expansion of the Fermi–Dirac occupancy for energies around the Fermi level.

Energy and wave function of a free electron

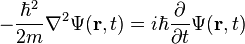

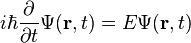

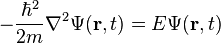

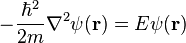

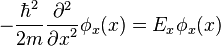

For a free particle the potential is  . The Schrödinger equation for such a particle, like the free electron, is[1][2][3]

. The Schrödinger equation for such a particle, like the free electron, is[1][2][3]

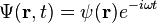

The wave function  can be split into a solution of a time dependent and a solution of a time independent equation. The solution of the time dependent equation is

can be split into a solution of a time dependent and a solution of a time independent equation. The solution of the time dependent equation is

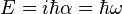

with energy

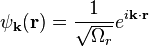

The solution of the time independent equation is

with a wave vector  .

.  is the volume of space where the electron can be found.

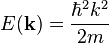

The electron has a kinetic energy

is the volume of space where the electron can be found.

The electron has a kinetic energy

The plane wave solution of this Schrödinger equation is

For solid state and condensed matter physics the time independent solution  is of major interest. It is the basis of electronic band structure models that are widely used in solid-state physics for model Hamiltonians like the nearly free electron model and the Tight binding model and different models that use a Muffin-tin approximation. The eigenfunctions of these Hamiltonians are Bloch waves which are modulated plane waves.

is of major interest. It is the basis of electronic band structure models that are widely used in solid-state physics for model Hamiltonians like the nearly free electron model and the Tight binding model and different models that use a Muffin-tin approximation. The eigenfunctions of these Hamiltonians are Bloch waves which are modulated plane waves.

Dielectric function of the electron gas

On a scale much larger than the inter atomic distance a solid can be viewed as an aggregate of a negatively charged plasma of the free electron gas and a positively charged background of atomic cores. The background is the rather stiff and massive background of atomic nuclei and core electrons which we will consider to be infinitely massive and fixed in space. The negatively charged plasma is formed by the valence electrons of the free electron model that are uniformly distributed over the interior of the solid. If an oscillating electric field is applied to the solid, the negatively charged plasma tends to move a distance x apart from the positively charged background. As a result the sample is polarized and there will be an excess charge at the opposite surfaces of the sample. The surface charge density is

which produces a restoring electric field in the sample

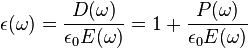

The dielectric function of the sample is expressed as

where  is the electric displacement and

is the electric displacement and  is the polarization density.

is the polarization density.

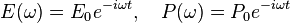

The electric field and polarization densities are

and the polarization per atom with n electrons is

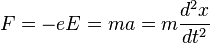

The force F of the oscillating electric field causes the electrons with charge e and mass m to accelerate with an acceleration a

which, after substitution of E, P and x, yields an harmonic oscillator equation.

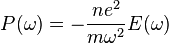

After a little algebra the relation between polarization density and electric field can be expressed as

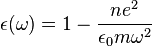

The frequency dependent dielectric function of the solid is

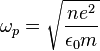

At a resonance frequency  , called the plasma frequency, the dielectric function changes sign from negative to positive and real part of the dielectric function drops to zero.

, called the plasma frequency, the dielectric function changes sign from negative to positive and real part of the dielectric function drops to zero.

This is a plasma oscillation resonance or plasmon. The plasma frequency is a direct measure of the square root of the density of valence electrons in a solid. Observed values are in reasonable agreement with this theoretical prediction for a large number of materials.[4] Below the plasma frequency, the dielectric function is negative and the field cannot penetrate the sample. Light with angular frequency below the plasma frequency will be totally reflected. Above the plasma frequency the light waves can penetrate the sample.

Solution of the Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation

For a free particle the potential is  , so the Schrödinger equation for the free electron is[1][2][3]

, so the Schrödinger equation for the free electron is[1][2][3]

This is a type of wave equation that has numerous kinds of solutions. One way of solving the equation is splitting it in a time-dependent oscillator equation and a space-dependent wave equation like

and

and substituting a product of solutions like

The Schrödinger equation can be split in a time dependent part and a time independent part.

Solution of the time dependent equation

The peculiar time dependent part of the Schrödinger equation is, unlike the Klein–Gordon equation for pions and most of the other well known wave equations, a first order in time differential equation with a 90° out of phase driving mechanism, while most oscillator equations are second order in time differential equations with 180° out of phase driving mechanisms.

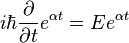

The equation that has to be solved is

.

.

The complex (imaginary) exponent is proportional to the energy

The imaginary exponent can be transformed to an angular frequency

The wave function now has a stationary and an oscillating part

The stationary part is of major importance to the physical properties of the electronic structure of matter.

Solution of the time independent equation

The wave function of free electrons is in general described as the solution of the time independent Schrödinger equation for free electrons

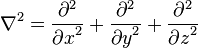

The Laplace operator in Cartesian coordinates is

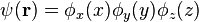

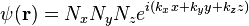

The wave function can be factorized for the three Cartesian directions

Now the time independent Schrödinger equation can be split in three independent parts for the three different Cartesian directions

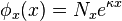

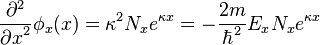

As a solution an exponential function is substituted in the time independent Schrödinger equation

The solution of

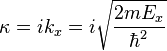

gives the exponent

which yields the wave equation

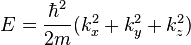

and the energy

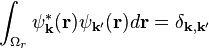

With the normalization

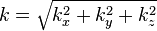

and the wave vector magnitude

we arrive at the plane wave solution with a wave function

for free electrons with a wave vector  and a kinetic energy

and a kinetic energy

in which  is the volume of space occupied by the electron.

is the volume of space occupied by the electron.

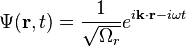

The traveling plane wave solution

The product of the time independent stationary wave solution and time dependent oscillator solution

gives the traveling plane wave solution

which is the final solution for the free electron wave function.

Fermi energy

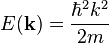

According to the Pauli principle, the electrons in the ground state occupy all the lowest-energy states, up to some Fermi energy  . Since the energy is given by

. Since the energy is given by

,

,

this corresponds to occupying all the states with wave vectors

, where

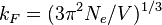

, where  is so-called Fermi wave vector, given by

is so-called Fermi wave vector, given by

,

,

where  is the total number of electrons in the system, and V is the total volume.

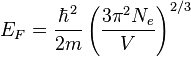

The Fermi energy is then

is the total number of electrons in the system, and V is the total volume.

The Fermi energy is then

In a nearly-free-electron model of a  -valent metal, one can replace

-valent metal, one can replace  with

with  , where

, where  is the total number of metal ions.

is the total number of metal ions.

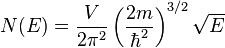

Density of states

The density of states (DOS) corresponds to electrons with a spherically-symmetric parabolic dispersion

,

,

with two electrons (one of each spin) per each "quantum" of the phase space,

.

In 3D, this corresponds to

.

In 3D, this corresponds to

,

,

where  is the total volume.

is the total volume.

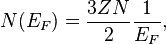

Combining the expressions for the Fermi energy and the DOS, one can show that the following relationship holds at the Fermi level:

where Z is the charge of each of the N metal ions in the crystal.

References

- 1 2 Albert Messiah (1999). Quantum Mechanics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40924-4.

- 1 2 Stephen Gasiorowicz (1974). Quantum Physics. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-29281-8.

- 1 2 Eugen Merzbacher (2004). Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.). Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-9971-5-1281-1.

- ↑ C. Kittel (1953–1976). Introduction to Solid State Physics. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-49024-5.

- Ashcroft, Neil (1976). Solid State Physics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-083993-1.

External links

- Brillouin Zone simple lattice diagrams by Thayer Watkins

- Brillouin Zone 3d lattice diagrams by Technion.

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package- "Brillouin Zones"

See also

- Fermi gas

- Bloch wave

- Nearly free electron model

- Free electron laser

- Particle in a one-dimensional lattice

- Paul Drude

- Arnold Sommerfeld

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||