United States presidential election, 1896

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Presidential election results map. Red denotes those won by McKinley/Hobart, Blue denotes states won by Bryan/Sewall OR the Populist ticket of Bryan/Watson. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1896 was the 28th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1896. It climaxed an intensely heated contest in which Republican candidate William McKinley (a former Governor of Ohio) defeated Democrat William Jennings Bryan (a former Representative from Nebraska) in one of the most dramatic and complex races in American history.

The 1896 campaign is often considered to be a realigning election that ended the old Third Party System and began the Fourth Party System.[2] McKinley forged a conservative coalition in which businessmen, professionals, skilled factory workers, and prosperous farmers were heavily represented. He was strongest in cities and in the Northeast, Upper Midwest, and Pacific Coast. Bryan was the nominee of the Democrats, the Populist Party, and the Silver Republicans. He presented his campaign as a crusade of the working man against the rich, who impoverished America by limiting the money supply, which was based on gold. Silver, he said, was in ample supply and if coined into money would restore prosperity while undermining the illicit power of the money trust. Bryan was strongest in the South, rural Midwest, and Rocky Mountain states. Bryan's moralistic rhetoric and crusading for inflation (based on a money supply based on silver as well as gold) alienated conservatives and especially German American voters. Turnout was very high, passing 90% of the eligible voters in many places.

For three years, the nation had been mired in a deep economic depression, marked by low prices, low profits, high unemployment, and violent strikes. Economic issues, especially silver or gold for the money supply, and tariffs, were central issues. Republican campaign manager Mark Hanna pioneered many modern campaign techniques, facilitated by a $3.5 million budget. He outspent Bryan by a factor of five. The Democratic Party's repudiation of its economically conservative Bourbon faction, represented by incumbent President Grover Cleveland, largely gave Bryan and his supporters control of the Democratic Party until the 1920s, and set the stage for Republican domination of the Fourth Party System and control of the White House for 28 of the next 36 years, interrupted only by the two terms of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Republican candidates:

- William McKinley, former governor of Ohio

- Thomas Brackett Reed of Maine, Speaker of the House of Representatives

- Matthew S. Quay of Pennsylvania, U.S. senator

- Levi P. Morton, governor of New York and former Vice President

- William B. Allison of Iowa, U.S. Senator

Candidates gallery

-

William McKinley from Ohio

-

Governor Levi P. Morton of New York

-

Senator William B. Allison from Iowa

At their convention in St. Louis, Missouri, held between June 16 and 18, 1896, the Republicans nominated William McKinley for president and New Jersey's Garret Hobart for vice-president. McKinley had just vacated the office of Governor of Ohio. Both candidates were easily nominated on first ballots.

McKinley's campaign manager, a wealthy and talented Ohio businessman named Mark Hanna, visited the leaders of large corporations and major banks after the Republican Convention to raise funds for the campaign. Given that many businessmen and bankers were terrified of Bryan's populist rhetoric and demand for ending the gold standard, Hanna had few problems in raising record amounts of money. In the end, Hanna raised a staggering $3.5 million for the campaign and outspent the Democrats by an estimated 5-to-1 margin. This sum would be equivalent to approximately $3 billion today.[3] Major McKinley was the last veteran of the American Civil War to be nominated for President by either major party.

| Presidential Ballot | |

| William McKinley | 661.5 |

|---|---|

| Thomas Brackett Reed | 84.5 |

| Matthew S. Quay | 61.5 |

| Levi P. Morton | 58 |

| William B. Allison | 35.5 |

| James D. Cameron | 1 |

| Vice Presidential Ballot | |

| Garret A. Hobart | 523.5 |

|---|---|

| H. Clay Evans | 287.5 |

| Morgan Bulkeley | 39 |

| James A. Walker | 24 |

| Charles W. Lippitt | 8 |

| Thomas Brackett Reed | 3 |

| Chauncey Depew | 3 |

| John Mellen Thurston | 2 |

| Frederick Dent Grant | 2 |

| Levi P. Morton | 1 |

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic candidates:

- William Jennings Bryan, former U.S. representative (Nebraska)

- Richard P. Bland, former U.S. representative (Missouri)

- Robert E. Pattison, former U.S. governor (Pennsylvania)

- Joseph Clay Styles Blackburn, U.S. senator (Kentucky)

- Horace Boies, former U.S. governor (Iowa)

- John R. McLean, newspaper publisher, (Ohio)

- Claude Matthews, U.S. governor (Indiana)

- Sylvester Pennoyer, former U.S. governor (Oregon)

-

Richard P. Bland from Missouri

-

Horace Boies from Iowa

-

Governor Claude Matthews of Indiana

-

Sylvester Pennoyer from Oregon

One month after McKinley's nomination, supporters of silver-backed currency took control of the Democratic convention held in Chicago on July 7–11. Most of the Southern and Western delegates were committed to implementing the "free silver" ideas of the Populist Party. The convention repudiated President Cleveland's gold standard policies and then repudiated Cleveland himself. This, however, left the convention wide open: there was no obvious successor to Cleveland. A two-thirds vote was required for the nomination and the silverites had it in spite of the extreme regional polarization of the delegates. In a test vote on an anti-silver measure, the Eastern states (from Maryland to Maine), with 28% of the delegates, voted 96% in favor. The other delegates voted 91% against, so the silverites could count on a majority of 67% of the delegates.[4]

An attorney, former congressman, and unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate named William Jennings Bryan filled the void. A superb orator, Bryan hailed from Nebraska and spoke for the farmers who were suffering from the economic depression following the Panic of 1893. At the convention, Bryan delivered one of the greatest political speeches in American history, the "Cross of Gold" Speech. Bryan presented a passionate defense of farmers and factory workers struggling to survive the economic depression, and he attacked big-city business owners and leaders as the cause of much of their suffering. He called for reform of the monetary system, an end to the gold standard, and government relief efforts for farmers and others hurt by the economic depression. Bryan's speech was so dramatic that after he had finished many delegates carried him on their shoulders around the convention hall. The speech united the convention delegates and earned Bryan their presidential nomination. He defeated his closest competitor, former Senator Richard "Silver Dick" Bland by a 3-to-1 margin. Arthur Sewall, a wealthy shipbuilder from Maine, was chosen as the vice-presidential nominee. It was felt that Sewall's wealth might encourage him to help pay some campaign expenses. At just 36 years of age, Bryan was only a year older than the minimum age required by the Constitution to be president. Bryan remains the youngest man ever nominated by a major party for president.

| (1-5) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | Unanimous | ||

| William J. Bryan | 137 | 197 | 219 | 280 | 652 | 930 | |

| Richard P. Bland | 235 | 281 | 291 | 241 | 11 | ||

| Robert E. Pattison | 97 | 100 | 97 | 97 | 95 | ||

| Joseph Blackburn | 82 | 41 | 27 | 27 | 0 | ||

| Horace Boies | 67 | 37 | 36 | 33 | 0 | ||

| John R. McLean | 54 | 53 | 54 | 46 | 0 | ||

| Claude Matthews | 37 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 0 | ||

| Benjamin Tillman | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Adlai E. Stevenson | 6 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Sylvester Pennoyer | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Henry M. Teller | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| William E. Russell | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| David B. Hill | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| James E. Campbell | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| David Turpie | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Blank | 178 | 160 | 162 | 161 | 162 | ||

| (1-5) | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | Unanimous | ||

| Arthur Sewall | 100 | 37 | 97 | 261 | 568 | 930 | |

| John R. McLean | 111 | 158 | 210 | 298 | 32 | ||

| Richard P. Bland | 62 | 294 | 255 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Joseph C. Sibley | 163 | 113 | 50 | 0 | 0 | ||

| George F. Williams | 76 | 16 | 15 | 9 | 9 | ||

| John W. Daniel | 11 | 0 | 6 | 54 | 36 | ||

| Walter Clark | 50 | 22 | 22 | 46 | 22 | ||

| James R. Williams | 22 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| William F. Harrity | 19 | 21 | 19 | 11 | 11 | ||

| Joseph Blackburn | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Horace Boies | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| J. Hamilton Lewis | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Robert E. Pattison | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| George W. Fithian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Henry M. Teller | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Stephen M. White | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Blank | 260 | 255 | 255 | 250 | 251 | ||

National Democratic Party (Gold Democrats) nomination

National Democratic candidates

- John M. Palmer of Illinois, U.S. senator

- Edward S. Bragg of Wisconsin, former U.S. representative

- William Freeman Vilas of Wisconsin, U.S. senator

- Grover Cleveland of New York, President of the United States

- John G. Carlisle of Kentucky, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

- Julius Sterling Morton of Nebraska, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture

- William Lyne Wilson of West Virginia, U.S. Postmaster General

- Henry Watterson of Kentucky, former U.S. representative

Candidates gallery

-

Edward S. Bragg from Wisconsin

-

Senator William Freeman Vilas from Wisconsin

-

Henry Watterson from Kentucky

The pro-gold Democrats reacted to Bryan's nomination with a mixture of anger, desperation, and confusion. A number of pro-gold Bourbon Democrats urged a "bolt" and the formation of a third party. In response, a hastily arranged assembly on July 24 organized the National Democratic Party. A follow-up meeting in August scheduled a nominating convention for September in Indianapolis and issued an appeal to fellow Democrats. In this document, the National Democratic Party portrayed itself as the legitimate heir to Presidents Jefferson, Jackson, and Cleveland.

Delegates from forty-one states gathered at the National Democratic Party's national nominating convention in Indianapolis on September 2. Some delegates planned to nominate Cleveland, but they relented after a telegram arrived stating that he would not accept. Senator William Freeman Vilas of Wisconsin, the main drafter of the National Democratic Party's platform, was a favorite of the delegates. However, Vilas refused to run as the party's sacrificial lamb. The choice was John M. Palmer, a 79-year-old former Senator from Illinois, was nominated for president.[5] Simon Bolivar Buckner, a 73-year-old former governor of Kentucky, was nominated unanimously by acclamation for vice-president. The ticket, symbolic of post-Civil War reconciliation, was the oldest in combined age in American history, and Palmer the oldest presidential candidate ever (Bryan was the youngest ever).

Despite their advanced ages, Palmer and Buckner embarked on a busy speaking tour, including visits to most major cities in the East. This won them considerable respect from the party faithful, although some found it hard to take the geriatric campaigning seriously. "You would laugh yourself sick could you see old Palmer," wrote Kenesaw Mountain Landis. "He has actually gotten it into his head he is running for office."[6] The Palmer ticket was considered to be a vehicle to elect McKinley for some Gold Democrats, such as William Collins Whitney and Abram Hewitt, the treasurer of the National Democratic Party, and they received quiet financial support from Mark Hanna. Palmer himself said at a campaign stop that if "this vast crowd casts its vote for William McKinley next Tuesday, I shall charge them with no sin."[7] There was even some cooperation with the Republican Party, especially in finances. The Republicans hoped that Palmer could draw enough Democratic votes from Bryan to tip marginal Midwestern and border states into McKinley's column. In a private letter, Hewitt underscored the "entire harmony of action" between both parties in standing against Bryan.[8]

However, the National Democratic Party was not merely an adjunct to the McKinley campaign. An important goal was to nurture a loyal remnant for future victory. Repeatedly they depicted Bryan's prospective defeat, and a credible showing for Palmer, as paving the way for ultimate recapture of the Democratic Party, as indeed happened in 1904.[9]

| Presidential Ballot | ||

| Ballot | 1st Before Shifts | 1st After Shifts |

|---|---|---|

| John M. Palmer | 757.5 | 769.5 |

| Edward S. Bragg | 130.5 | 118.5 |

Populist Party nomination

Populist candidates:

- William Jennings Bryan, former U.S. representative (Nebraska)

- Seymour F. Norton of Illinois, writer

Candidates gallery

Several third parties were active in 1896. By far the most prominent was the Populist Party. Formed in 1892, the Populists represented the philosophy of agrarianism (derived from Jeffersonian democracy) holding that farming was a superior way of life that was being exploited by bankers and middlemen. They attracted cotton farmers in the South and wheat farmers in the West, but very few farmers in the Northeast,the South, West, and rural Midwest. In the 1892 presidential election Populist candidate James B. Weaver carried four states, and in 1894 the Populists scored victories in congressional and state legislature races in a number of Southern and Western states. In the Southern states, including Alabama, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, the wins were obtained by electoral fusion with the Republicans against the dominant Bourbon Democrats, whereas in the rest of the country, fusion, if practiced, was typically undertaken with the Democrats, as in the state of Washington.[10][11] By 1896, some Populists believed that they could replace the Democrats as the main opposition party to the Republicans. However, the Democrats' nomination of Bryan, who supported many Populist goals and ideas, placed the party in a dilemma. Torn between choosing their own presidential candidate or supporting Bryan, the party leadership decided that nominating their own candidate would simply divide the forces of reform and hand the election to the more conservative Republicans. At their national convention in 1896, the Populists chose Bryan as their presidential nominee. However, to demonstrate that they were still independent from the Democrats, the Populists also chose Georgia Senator Thomas E. Watson as their vice-presidential candidate instead of Arthur Sewall. Bryan eagerly accepted the Populist nomination, but was vague as to whether, if elected, he would choose Watson as his vice-president instead of Sewall. With this election, the Populists began to be absorbed into the Democratic Party; within a few elections the party would disappear completely. The 1896 election was particularly detrimental to the Populist Party in the South, dividing the party between members who favored cooperation with the Democrats to achieve results at the national level and members who favored cooperation with the Republicans to achieve reform at a state level.

As a result of the double nomination, in many states both the Bryan-Sewall Democratic ticket and the Bryan-Watson Populist ticket appeared on the ballot. Although the Populist ticket did not win the popular vote in any state, 27 electors for Bryan cast their vice-presidential vote for Watson instead of Sewall. (The votes came from the following states: Arkansas 3, Louisiana 4, Missouri 4, Montana 1, Nebraska 4, North Carolina 5, South Dakota 2, Utah 1, Washington 2, Wyoming 1.)

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| William Jennings Bryan | 1,042 | Thomas E. Watson | 469.5 |

| Seymour F. Norton | 321 | Arthur Sewall | 257.5 |

| Scattering | 12 | ||

Silver Party

Silver candidates:

- William Jennings Bryan, former U.S. representative (Nebraska)

- Henry M. Teller, U.S. Senator from Colorado

Candidates gallery

-

Senator Henry M. Teller from Colorado

(declined)

With the Republican Party platform calling for strong support for the gold standard, many western Republicans walked out of the Republican Convention and formed the National Silver Party. Many began to push for the nomination of Colorado Senator Henry Moore Teller who was the leader of the party, but with the nomination of William Jennings Bryan in Chicago and the adoption of his Pro-Silver platform, it was decided that they should unite behind the Democratic ticket.[12] The Bryan campaign swept to victory across the Mountain states because the dominant issue in those thinly-populated mining areas was silver.[13]

Socialist Labor nomination

The Socialist Labor Convention was held in New York City on July 9, 1896. The convention nominated Charles Matchett of New York and Matthew Maguire of New Jersey. Its platform favored reduction in hours of labor; possession by the federal government of mines, railroads, canals, telegraphs, and telephones; possession by municipalities of water-works, gas-works, and electric plants; the issue of money by the federal government alone; the employment of the unemployed by the public authorities; abolition of the veto power; abolition of the United States Senate; women's suffrage; and uniform criminal law throughout the Union.[14]

Prohibition Party

The Prohibition Party split into a "narrow gauge," or single-issue anti-liquor party and a "broad gauge" group (later known as the National Prohibition Party) that supported many reforms, including free silver. The split occurred when a motion for the Party to endorse free silver, put forward by Charles Bentley, was defeated by an overwhelming margin of 650-160. Although Bryan himself later became a champion of prohibition, his position was unknown in 1896.[15]

"Narrow Gauge" Prohibition nomination

"Narrow Gauge" Prohibition ticket:

-

Joshua Levering, Baptist leader from Maryland

-

Lawyer and Former Mayor Hale Johnson from Illinois

"Broad Gauge" Prohibition Nomination

"Broad Gauge" Prohibition ticket:

-

Charles E. Bentley, Baptist minister from Nebraska

-

James Southgate, State Party Chair from North Carolina

Campaign strategies

While the Republican Party entered 1896 assuming that the Democrats were in shambles and victory would be easy, especially after the unprecedented Republican landslide of 1894, the nationwide emotional response to the Bryan candidacy changed everything. By summer it appeared Bryan was ahead in the South and West, and probably also in the Midwest.[16][17] An entirely new strategy was called for and was produced by the McKinley campaign. It was designed to educate voters in the money issues, to demonstrate silverite fallacies, and to portray Bryan himself as a dangerous crusader. McKinley would be portrayed as the safe and sound champion of jobs and sound money, with his high tariff proposals guaranteed to return prosperity for everyone. The McKinley campaign would be national and centralized, using the Republican National Committee as the tool of the candidate, instead of the state parties' tool.[18] Furthermore the McKinley campaign stressed his pluralistic commitment to prosperity for all groups (including minorities).[19]

Financing

The McKinley campaign invented a new form of campaign financing that has dominated American politics ever since.[20] Instead of asking office holders to return a cut of their pay, Hanna went to financiers and industrialists and made a business proposition. He explained that Bryan would win if nothing happened, and that the McKinley team had a winning counterattack that would be very expensive. He then would ask them how much it was worth to the business not to have Bryan as president. He suggested an amount and was happy to take a check. Hanna had moved beyond partisanship and campaign rhetoric to a businessman's thinking about how to achieve a desired result. He raised $3.5 million. Hanna brought in banker Charles G. Dawes to run the Chicago office and spend about $2 million in the critical region.[21]

Meanwhile, traditional funders of the Democratic Party (mostly financiers from the Northeast) rejected Bryan, although he did manage to raise about $500,000. Some of it came from businessmen with interests in silver mining.

The financial disparity grew larger and larger as the Republican funded more and more rallies, speeches, and torchlight parades, as well as hundreds of millions of pamphlets attacking Bryan and praising McKinley. Lacking a systematic fund-raising system, Bryan was unable to tap his potential supporters, and he had to rely on passing the hat at rallies. National Chairman Jones pleaded, "No matter in how small sums, no matter by what humble contributions, let the friends of liberty and national honor contribute all they can."[22]

Republican attacks on Bryan

Increasingly, the Republicans personalized their attacks on Bryan as a dangerous religious fanatic.[23] The counter-crusading rhetoric focused on Bryan as a reckless revolutionary whose policies would destroy the economic system.[24] Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld was running for re-election after having pardoned several of the anarchists convicted in the Haymarket bombings. Republican posters and speeches linked Altgeld and Bryan as two dangerous anarchists.[25] The Republican Party tried any number of tactics to ridicule Bryan's economic policies. In one case they printed fake dollar bills which had Bryan's face and read "IN GOD WE TRUST...FOR THE OTHER 53 CENTS," thus illustrating their claim that a dollar bill would be worth only 47 cents if it was backed by silver instead of gold.[26]

Ethnic responses

The Democratic Party in Eastern and Midwestern cities had a strong German base, which was alienated by free silver and inflationist panaceas. They showed little enthusiasm for Bryan, although many were worried that a Republican victory would bring prohibition into play.[27][28] The Irish Catholics disliked Bryan's revivalistic rhetoric and worried about prohibition as well. However their leaders decided to stick with Bryan since the departure of so many Bourbon businessmen from the party left the Irish increasingly in control.[29][30]

Labor unions and skilled workers

The Bryan campaign appealed first of all to farmers. It told urban workers that their return to prosperity was possible only if the farmers prospered first. Bryan made the point bluntly in the "Cross of Gold" speech, delivered in Chicago just 25 years after that city had indeed burned down:[31]

- "Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again; but destroy our farms, and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country."

Juxtaposing "our farms" and "your cities" did not go over well in cities; they voted 59% for McKinley. Among the industrial cities Bryan carried only two (Troy, New York, and Fort Wayne, Indiana).[32]

The main labor unions were reluctant to endorse Bryan because their members feared inflation.[33][34] Railroad workers especially worried that Bryan's silver programs would bankrupt the railroads, which were in shaky financial condition in the depression and whose bonds were payable in gold. Factory workers saw no advantage in inflation to help miners and farmers, because their urban cost of living would shoot up and they would be hurt. The McKinley campaign gave special attention to skilled workers, especially in the Midwest and adjacent states.[35] Secret polls show that large majorities of railroad and factory workers voted for McKinley.[36]

The fall campaign

Throughout the campaign the South and Mountain states appeared certain to vote for Bryan, whereas the East was certain for McKinley. In play were the Midwest and the Border States.

The Republican Party amassed an unprecedented war chest at all levels—national, state and local. Outspent and shut out of the party's traditional newspapers, Bryan decided his best chance to win the election was to conduct a vigorous national speaking tour by train. His fiery crusading rhetoric to huge audiences would make his campaign a newsworthy story that the hostile press would have to cover, and he could speak to the voters directly instead of through editorials. He was the first presidential candidate since Stephen Douglas in 1860 to canvass directly, and the first ever to criss-cross the nation and meet voters in person.

The novelty of seeing a visiting presidential candidate, combined with Bryan's spellbinding oratory and the passion of his believers, generated huge crowds. Silverites welcomed their hero with all-day celebrations of parades, band music, picnic meals, endless speeches, and undying demonstrations of support. Bryan focused his efforts on the Midwest, which everyone agreed would be the decisive battleground in the election. In just 100 days, Bryan gave over 500 speeches to several million people. His record was 36 speeches in one day in St. Louis. Relying on just a few hours of sleep a night, he traveled 18,000 miles by rail[37] to address five million people, often in a hoarse voice; he would explain that he left his real voice at the previous stops where it was still rallying the people.

In contrast to Bryan's dramatic efforts, McKinley conducted a novel "front porch" campaign from his home in Canton, Ohio. Instead of having McKinley travel to see the voters, Mark Hanna brought 500,000 voters by train to McKinley's home. Once there, McKinley would greet the men from his porch. His well-organized staff prepared both the remarks of the visiting delegation and the candidate's responses, focusing the comments on the assigned topic of the day. The remarks were issued to the newsmen and telegraphed nationwide to appear in the next day's papers. Bryan, with practically no staff, gave much the same talk over and over again. McKinley labeled Bryan's proposed social and economic reforms as a serious threat to the national economy. With the depression following the Panic of 1893 coming to an end, support for McKinley's more conservative economic policies increased, while Bryan's more radical policies began to lose support among Midwestern farmers and factory workers.

To ensure victory, Hanna paid large numbers of Republican orators (including Theodore Roosevelt) to travel around the nation denouncing Bryan as a dangerous radical. There were also reports that some potentially Democratic voters were intimidated into voting for McKinley. For example, some factory owners posted signs the day before the election announcing that, if Bryan won the election, the factory would be closed and the workers would lose their jobs.

Bryan's midsummer surge in the Midwest played out as the intense Republican counter-crusade proved effective. Bryan spent most of October in the Midwest, making 160 of his final 250 speeches there. Morgan noted, "full organization, Republican party harmony, a campaign of education with the printed and spoken word would more than counteract" Bryan's speechmaking.[38]

Several of Bryan's advisors recommended additional campaigning in the Upper South States of Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. Another plan called for a coastal tour from Washington State to Southern California. Bryan however, opted to concentrate in the Mid-West and to launch a unity tour into the heavily Republican Northeast. Bryan saw no chance of winning in New England but felt that he needed to make a truly national appeal. On election day the results from the Pacific Coast and Upper South would be the closest of the election.

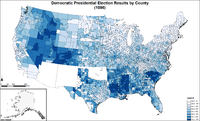

Results

McKinley secured a solid victory by carrying the core of the East and Northeast, while Bryan did well among the farmers of the South, West, and rural Midwest. The large German-American voting bloc supported McKinley, who gained large majorities among the middle class, skilled factory workers, railroad workers, and large-scale farmers. The national popular vote was rather close, as McKinley took 51% to Bryan's 47%. In the electoral college McKinley won in a landslide, receiving 271 electoral votes (61%) to Bryan's 176 (224 were needed to win).

The National Democrats did not carry any states, but they did divide the Democratic vote in some states and helped the Republicans to carry the state of Kentucky. Gold Democrats made much of the fact that Palmer's small vote in Kentucky was higher than McKinley's thin margin in that state. From this, they concluded that Palmer had siphoned off needed Democratic votes and hence thrown the state to McKinley. However, McKinley would have won the overall election even if he had lost Kentucky to Bryan.

Mayor Tom L. Johnson of Cleveland, Ohio, summed up the campaign as the "first great protest of the American people against monopoly - the first great struggle of the masses in our country against the privileged classes."

General results

McKinley received a little more than seven million votes, Bryan a little less than six and a half million, about 800,000 in excess of the Democratic vote in 1892. It was larger than the Democratic Party was to poll in 1900, 1904, or 1912. It was somewhat less, however, than the combined vote for the Democratic and Populist nominees had been in 1892. In contrast, McKinley received nearly 2,000,000 more votes than had been cast for Benjamin Harrison, the Republican nominee, in 1892. The Republican vote was to be but slightly increased during the next decade.

Geography of results

One-half of the total vote of the nation was polled in 8 states carried by McKinley (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin). In these states, Bryan not only ran far behind the Republican candidate, but also polled considerably less than half of his total vote.[40]

In only one other section, in the six states of New England, was the Republican lead great; the Republican vote (614,972) was more than twice the Democratic vote (242,938), and every county was carried by the Republicans.[41]

The West North Central section gave a slight lead to McKinley, as did the Pacific section. But within these sections, the states of Missouri, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Washington were carried by Bryan.

In the South Atlantic section and in the East South Central section, the Democratic lead was pronounced, and in the West South Central section and in the Mountain section, the vote for Bryan was overwhelming. In these four sections, comprising 21 states, McKinley carried only 322 counties and he carried only 4 states - Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and West Virginia.

A striking feature of this examination of the state returns is found in the overwhelming lead for one or the other party in 22 of the 45 states. It was true of the McKinley vote in every New England state and in New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. It was also true of the Bryan vote in 8 states of the lower South and 5 states of the Mountain West. Sectionalism was thus marked in this first election of the Fourth Party System.

Southern votes

In the South, there were numerous Republican counties, notably in Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Virginia. Even in Georgia, a state in the Deep South, there were counties returning Republican majorities. This was the result of an attempt by Republican politicians to heal sectional resentment and make the South competitive.

While traveling the South in 1895, McKinley realized that many conservative Southern whites were angry at the populist radicals who controlled the state's Democratic Party. White businessmen of Georgia wanted the support of a party that would oppose regulation and taxation as long as it would allow them to preserve white supremacy. The possibility of preserving white supremacy without offending loyal black Republicans seemed like a possibility after black leader Booker T. Washington gave a speech in 1895 that proposed the "Atlanta Compromise", which held that whites should support blacks in their struggle for economic independence as they learned trade and industry, and in return blacks would not challenge the political or social order of Jim Crow. The policy was somewhat of a success because McKinley won 37% of Georgia's vote (the closest a Republican would come to winning the state until 1928).

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Pct | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Elect. vote | ||||

| William McKinley | Republican | Ohio | 7,111,607 | 51.03% | 271 | Garret A. Hobart | New Jersey | 271 |

| William Jennings Bryan | Democratic - People's | Nebraska | 6,509,052(a) | 46.70% | 176 | Arthur Sewall(b) | Maine | 149 |

| Thomas E. Watson(c) | Georgia | 27 | ||||||

| John M. Palmer | National Democratic | Illinois | 134,645 | 0.97% | 0 | Simon Bolivar Buckner | Kentucky | 0 |

| Joshua Levering | Prohibition | Maryland | 131,312 | 0.94% | 0 | Hale Johnson | Illinois | 0 |

| Charles Matchett | Socialist Labor | New York | 36,373 | 0.26% | 0 | Matthew Maguire | New Jersey | 0 |

| Charles Eugene Bentley | National Prohibition | Nebraska | 13,968 | 0.10% | 0 | James Southgate | North Carolina | 0 |

| Other | 1,570 | 0.01% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 13,936,957 | 100% | 447 | 447 | ||||

| Needed to win | 224 | 224 | ||||||

(a) Includes 222,583 votes as the People's nominee

(b) Sewall was Bryan's Democratic running mate.

(c) Watson was Bryan's People's running mate.

Source (Popular Vote): [42]

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

-

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by state

| States won by McKinley/Hobart |

| States won by Bryan/Sewall or Bryan/Watson |

| William McKinley Republican |

William Jennings Bryan Democratic/Populist |

John Palmer National Democrat |

Joshua Levering Prohibition |

Charles Matchett Socialist Labor |

Charles Bentley National Prohibition |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 11 | 55,673 | 28.61 | - | 130,298 | 66.96 | 11 | 6,375 | 3.28 | - | 2,234 | 1.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -74,625 | -38.35 | 194,580 | AL |

| Arkansas | 8 | 37,512 | 25.12 | - | 110,103 | 73.72 | 8 | - | - | - | 839 | 0.56 | - | - | - | - | 893 | 0.60 | - | -72,591 | -48.61 | 149,347 | AR |

| California | 9 | 146,688 | 49.16 | 8 | 144,766 | 48.51 | 1 | 1,730 | 0.58 | - | 2,573 | 0.86 | - | 1,611 | 0.54 | - | 1,047 | 0.35 | - | 1,922 | 0.64 | 298,419 | CA |

| Colorado | 4 | 26,271 | 13.86 | - | 161,005 | 84.95 | 4 | 1 | 0.00 | - | 1,717 | 0.91 | - | 159 | 0.08 | - | 386 | 0.20 | - | -134,734 | -71.09 | 189,539 | CO |

| Connecticut | 6 | 110,285 | 63.24 | 6 | 56,740 | 32.54 | - | 4,336 | 2.49 | - | 1,806 | 1.04 | - | 1,223 | 0.70 | - | - | - | - | 53,545 | 30.70 | 174,390 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 20,450 | 53.18 | 3 | 16,574 | 43.10 | - | 966 | 2.51 | - | 466 | 1.21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3,876 | 10.08 | 38,456 | DE |

| Florida | 4 | 11,298 | 24.30 | - | 32,756 | 70.46 | 4 | 1,778 | 3.82 | - | 656 | 1.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -21,458 | -46.16 | 46,488 | FL |

| Georgia | 13 | 59,395 | 36.56 | - | 93,885 | 57.78 | 13 | 3,670 | 2.26 | - | 5,483 | 3.37 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -34,490 | -21.23 | 162,480 | GA |

| Idaho | 3 | 6,314 | 21.32 | - | 23,135 | 78.10 | 3 | - | - | - | 172 | 0.58 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -16,821 | -56.79 | 29,621 | ID |

| Illinois | 24 | 607,130 | 55.66 | 24 | 465,613 | 42.68 | - | 6,390 | 0.59 | - | 9,796 | 0.90 | - | 1,147 | 0.11 | - | 793 | 0.07 | - | 141,517 | 12.97 | 1,090,869 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 323,754 | 50.82 | 15 | 305,573 | 47.96 | - | 2,145 | 0.34 | - | 3,056 | 0.48 | - | 324 | 0.05 | - | 2,267 | 0.36 | - | 18,181 | 2.85 | 637,119 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 289,293 | 55.47 | 13 | 223,741 | 42.90 | - | 4,516 | 0.87 | - | 3,192 | 0.61 | - | 453 | 0.09 | - | 352 | 0.07 | - | 65,552 | 12.57 | 521,547 | IA |

| Kansas | 10 | 159,345 | 47.63 | - | 171,675 | 51.32 | 10 | 1,209 | 0.36 | - | 1,698 | 0.51 | - | - | - | - | 620 | 0.19 | - | -12,330 | -3.69 | 334,547 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 218,171 | 48.93 | 12 | 217,894 | 48.86 | 1 | 5,084 | 1.14 | - | 4,779 | 1.07 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 277 | 0.06 | 445,928 | KY |

| Louisiana | 8 | 22,037 | 21.81 | - | 77,175 | 76.38 | 8 | 1,834 | 1.82 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -55,138 | -54.57 | 101,046 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 80,403 | 67.90 | 6 | 34,587 | 29.21 | - | 1,867 | 1.58 | - | 1,562 | 1.32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 45,816 | 38.69 | 118,419 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 136,959 | 54.73 | 8 | 104,150 | 41.62 | - | 2,499 | 1.00 | - | 5,918 | 2.36 | - | 587 | 0.23 | - | 136 | 0.05 | - | 32,809 | 13.11 | 250,249 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 15 | 278,976 | 69.47 | 15 | 105,711 | 26.32 | - | 11,749 | 2.93 | - | 2,998 | 0.75 | - | 2,114 | 0.53 | - | - | - | - | 173,265 | 43.15 | 401,568 | MA |

| Michigan | 14 | 293,336 | 53.77 | 14 | 237,166 | 43.47 | - | 6,923 | 1.27 | - | 4,978 | 0.91 | - | 293 | 0.05 | - | 1,816 | 0.33 | - | 56,170 | 10.30 | 545,585 | MI |

| Minnesota | 9 | 193,503 | 56.62 | 9 | 139,735 | 40.89 | - | 3,222 | 0.94 | - | 4,348 | 1.27 | - | 954 | 0.28 | - | - | - | - | 53,768 | 15.73 | 341,762 | MN |

| Mississippi | 9 | 4,819 | 6.92 | - | 63,355 | 91.04 | 9 | 1,021 | 1.47 | - | 396 | 0.57 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -58,536 | -84.11 | 69,591 | MS |

| Missouri | 17 | 304,940 | 45.25 | - | 363,667 | 53.96 | 17 | 2,365 | 0.35 | - | 2,043 | 0.30 | - | 599 | 0.09 | - | 292 | 0.04 | - | -58,727 | -8.71 | 673,906 | MO |

| Montana | 3 | 10,509 | 19.71 | - | 42,628 | 79.93 | 3 | - | - | - | 193 | 0.36 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -32,119 | -60.23 | 53,330 | MT |

| Nebraska | 8 | 103,064 | 46.18 | - | 115,007 | 51.53 | 8 | 2,885 | 1.29 | - | 1,243 | 0.56 | - | 186 | 0.08 | - | 797 | 0.36 | - | -11,943 | -5.35 | 223,182 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 1,938 | 18.79 | - | 8,376 | 81.21 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -6,438 | -62.42 | 10,314 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 57,444 | 68.66 | 4 | 21,650 | 25.88 | - | 3,520 | 4.21 | - | 779 | 0.93 | - | 228 | 0.27 | - | 49 | 0.06 | - | 35,794 | 42.78 | 83,670 | NH |

| New Jersey | 10 | 221,535 | 59.68 | 10 | 133,695 | 36.02 | - | 6,378 | 1.72 | - | - | - | - | 3,986 | 1.07 | - | 5,617 | 1.51 | - | 87,840 | 23.66 | 371,211 | NJ |

| New York | 36 | 819,838 | 57.58 | 36 | 551,369 | 38.72 | - | 18,950 | 1.33 | - | 16,052 | 1.13 | - | 17,667 | 1.24 | - | - | - | - | 268,469 | 18.85 | 1,423,876 | NY |

| North Carolina | 11 | 155,122 | 46.82 | - | 174,408 | 52.64 | 11 | 578 | 0.17 | - | 635 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | 222 | 0.07 | - | -19,286 | -5.82 | 331,337 | NC |

| North Dakota | 3 | 26,335 | 55.57 | 3 | 20,686 | 43.65 | - | - | - | - | 358 | 0.76 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5,649 | 11.92 | 47,391 | ND |

| Ohio | 23 | 525,991 | 51.86 | 23 | 477,497 | 47.08 | - | 1,858 | 0.18 | - | 5,068 | 0.50 | - | 1,165 | 0.11 | - | 2,716 | 0.27 | - | 48,494 | 4.78 | 1,014,295 | OH |

| Oregon | 4 | 48,779 | 50.07 | 4 | 46,739 | 47.98 | - | 977 | 1.00 | - | 919 | 0.94 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2,040 | 2.09 | 97,414 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 32 | 728,300 | 60.98 | 32 | 433,228 | 36.27 | - | 11,000 | 0.92 | - | 19,274 | 1.61 | - | 1,683 | 0.14 | - | 870 | 0.07 | - | 295,072 | 24.71 | 1,194,355 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 37,437 | 68.33 | 4 | 14,459 | 26.39 | - | 1,166 | 2.13 | - | 1,160 | 2.12 | - | 558 | 1.02 | - | - | - | - | 22,978 | 41.94 | 54,785 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 9,313 | 13.51 | - | 58,801 | 85.30 | 9 | 824 | 1.20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -49,488 | -71.79 | 68,938 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 41,042 | 49.48 | - | 41,225 | 49.70 | 4 | - | - | - | 683 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -183 | -0.22 | 82,950 | SD |

| Tennessee | 12 | 148,683 | 46.33 | - | 167,168 | 52.09 | 12 | 1,953 | 0.61 | - | 3,099 | 0.97 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -18,485 | -5.76 | 320,903 | TN |

| Texas | 15 | 167,520 | 30.75 | - | 370,434 | 68.00 | 15 | 5,046 | 0.93 | - | 1,786 | 0.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -202,914 | -37.25 | 544,786 | TX |

| Utah | 3 | 13,491 | 17.27 | - | 64,607 | 82.70 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -51,116 | -65.43 | 78,119 | UT |

| Vermont | 4 | 51,127 | 80.08 | 4 | 10,640 | 16.66 | - | 1,331 | 2.08 | - | 733 | 1.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 40,487 | 63.41 | 63,847 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 135,379 | 45.94 | - | 154,708 | 52.50 | 12 | 2,129 | 0.72 | - | 2,350 | 0.80 | - | 108 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | -19,329 | -6.56 | 294,674 | VA |

| Washington | 4 | 39,153 | 41.84 | - | 53,314 | 56.97 | 4 | - | - | - | 968 | 1.03 | - | - | - | - | 148 | 0.16 | - | -14,161 | -15.13 | 93,583 | WA |

| West Virginia | 6 | 105,379 | 52.23 | 6 | 94,480 | 46.83 | - | 678 | 0.34 | - | 1,220 | 0.60 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10,899 | 5.40 | 201,757 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 268,135 | 59.93 | 12 | 165,523 | 37.00 | - | 4,584 | 1.02 | - | 7,507 | 1.68 | - | 1,314 | 0.29 | - | 346 | 0.08 | - | 102,612 | 22.93 | 447,409 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 10,072 | 47.75 | - | 10,861 | 51.49 | 3 | - | - | - | 159 | 0.75 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -789 | -3.74 | 21,092 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 447 | 7,112,138 | 51.02 | 271 | 6,510,807 | 46.71 | 176 | 133,537 | 0.96 | - | 124,896 | 0.90 | - | 36,359 | 0.26 | - | 19,367 | 0.14 | - | 601,331 | 4.31 | 13,938,674 | US |

Close states

Margin of victory less than 5% (81 electoral votes):

- Kentucky, 0.06%

- South Dakota, 0.22%

- California, 0.64%

- Oregon, 2.09%

- Indiana, 2.85%

- Kansas, 3.69%

- Wyoming, 3.74%

- Ohio, 4.78%

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (66 electoral votes):

- Nebraska, 5.35%

- West Virginia, 5.40%

- Tennessee, 5.76%

- North Carolina, 5.82%

- Virginia, 6.56%

- Missouri, 8.71%

Geography of Results

Cartographic Gallery

-

Map of presidential election results by county.

-

Map of Republican presidential election results by county.

-

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county.

-

Map of "other" presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county.

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Zapata County, Texas 94.34%

- Leslie County, Kentucky 91.39%

- Addison County, Vermont 89.17%

- Unicoi County, Tennessee 89.04%

- Keweenaw County, Michigan 88.96%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- West Carroll Parish, Louisiana 99.84%

- Leflore County, Mississippi 99.68%

- Smith County, Mississippi 99.26%

- Pitkin County, Colorado 99.21%

- Neshoba County, Mississippi 99.15%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Populist)

- Madera County, California 62.80%

- Lake County, California 61.95%

- Stanislaus County, California 59.00%

- San Benito County, California 57.59%

- San Luis Obispo County, California 56.37%

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- First inauguration of William McKinley

- Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

- Third Party System

- United States House election, 1896

References

- ↑ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- ↑ Williams (2010)

- ↑ See Paul Krugman, Conscience of a Liberal page 23

- ↑ Walter Dean Burnham, "The System of 1896: An Analysis," in Paul Kleppner et al., The Evolution of American Electoral Systems (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981), 147—202 at pp. 158–60

- ↑ "THE DEMOCRATIC TICKET; Palmer and Buckner Nominated at Indianapolis" (PDF). The New York Times. September 4, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ↑ Paul W. Glad (1964). McKinley, Bryan, and the people. Lippincott. p. 187.

- ↑ Jones, 1896 p 273

- ↑ Allan Nevins (1935). Abram S. Hewitt: with some account of Peter Cooper. Harper & Brothers. p. 564.

- ↑ James A. Barnes (1931). John G. Carlisle, financial statesman. Dodd, Mead. p. 470.

- ↑ "African". History.missouristate.edu. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Senate and House Secured; Republican control in the next Conress assured. The House of Representatives Repub- lican by More than Two -- thirds Ma- jority -- Possible Loss of a Repub- lican Senator from the State of Washington -- Republicans and Pop- ulists Will Organize the Senate and Divide the Patronage". The New York Times. November 9, 1894. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ↑ Jones, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Elmer Ellis (1941). Henry Moore Teller: defender of the West. Caxton. pp. ch 18. ch 18

- ↑ Davis, William Thomas (February 22, 2008). The New England States. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ Jack S. Blocker; David M. Fahey; Ian R. Tyrrell (2003). Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 495 vol 1. ISBN 9781576078334.

- ↑ Jones, 1896 p 277

- ↑ Phillips, McKinley pp 74-75

- ↑ Daniel Klinghard (2010). The Nationalization of American Political Parties, 1880-1896. Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–28. ISBN 9780521192811.

- ↑ William C. Spragens (1988). Popular Images of American Presidents. Greenwood. pp. 158–59. ISBN 9780313228995.

- ↑ William T. Horner (2010). Ohio's Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man & Myth. Ohio University Press. pp. 195–9. ISBN 9780821418949.

- ↑ John E. Pixton, Jr., "Charles G. Dawes and the Mckinley Campaign," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1955) 48#3 pp. 283-306 in JSTOR

- ↑ William Jennings Bryan (1896). The First Battle: A Story of the Campaign of 1896. W.B. Conkey. p. 292.

- ↑ Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer (1937). A History of the United States Since the Civil War: 1888-1901. Macmillian. p. 437.

- ↑ William C. Spragens (1988). Popular Images of American Presidents. Greenwood. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-313-22899-5.

- ↑ Alice Fahs; Joan Waugh (2004). The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture. U. of North Carolina Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780807855720.

- ↑ Jackson Lears (2010). Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877-1920. Harper Collins. p. 188. ISBN 9780060747503.

- ↑ Robert Booth Fowler (2008). Wisconsin Votes: An Electoral History. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780299227401.

- ↑ Paul Kleppner (1970). The cross of culture: a social analysis of midwestern politics, 1850-1900. Free Press. pp. 323–35.

- ↑ Richard Franklin Bensel (2000). The Political Economy of American Industrialization, 1877-1900. Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-521-77604-2.

- ↑ The politics of depression: political behavior in the Northeast, 1893-1896. Oxford University Press. 1972. p. 218.

- ↑ Paul Kleppner (1970). The cross of culture: a social analysis of midwestern politics, 1850-1900. Free Press. p. 304.

- ↑ William Diamond, American Historical Review (1941) 46#2 pp. 281-305 at pp. 285, 297 in JSTOR

- ↑ Elizabeth Sanders (1999). Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877-1917. U. of Chicago Press. p. 434. ISBN 9780226734774.

- ↑ Matthew Hild (2007). Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. U. of Georgia Press. pp. 191–92. ISBN 9780820328973.

- ↑ William D. Harpine (2006). From the Front Porch to the Front Page: McKinley and Bryan in the 1896 Presidential Campaign. Texas A&M University Press. p. 117. ISBN 9781585445592.

- ↑ Richard J. Jensen (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896. U. of Chicago Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9780226398259.

- ↑ Jeffrey G. Mora, "William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Campaign," Railroad History, (Fall/Winter 2008), Issue 199, pp 72-80,

- ↑ H. Wayne Morgan (1969). From Hayes to McKinley; national party politics, 1877-1896. Syracuse University Press.

- ↑ The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932 – Google Books. Stanford University Press. 1934. ISBN 9780804716963. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 4

- ↑ The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 4-5

- ↑ History of American Presidential Elections 1789-1968, Volume II, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

- ↑ "1896 Presidential General Election Data - National". Retrieved March 18, 2013.

Further reading

- Barnes, James A. (1947). "Myths of the Bryan Campaign". Mississippi Valley Historical Review 34 (3): 367–404. doi:10.2307/1898096. JSTOR 1898096.

- Beito, David T.; Beito, Linda Royster (2000). "Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900". Independent Review 4: 555–575.

- Bensel, Richard Franklin (2008). Passion and Preferences: William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Democratic National Convention. Cambridge U.P. ISBN 9780521717625.

- Coletta, Paolo E. (1964). William Jennings Bryan, Political Evangelist. vol. 1. University of Nebraska Press.

- Diamond, William, "Urban and Rural Voting in 1896," American Historical Review, (1941) 46#2 pp. 281–305 in JSTOR

- Durden, Robert F. "The 'Cow-bird' Grounded: The Populist Nomination of Bryan and Tom Watson in 1896," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1963) 50#3 pp. 397–423 in JSTOR

- Fite, Gilbert C. (2001). "The Election of 1896". In Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., ed. History of American Presidential Elections. vol. 2.

- Fite, Gilbert C. (1960). "Republican Strategy and the Farm Vote in the Presidential Campaign of 1896". American Historical Review 65 (4): 787–806. doi:10.2307/1849404. JSTOR 1849404.

- Glad, Paul W. (1964). McKinley, Bryan, and the People. ISBN 0-397-47048-7.

- Graff, Henry F. (2002). Grover Cleveland. ISBN 0-8050-6923-2.

- Harpine, William D. From the Front Porch to the Front Page: McKinley and Bryan in the 1896 Presidential Campaign (2006) focus on the speeches and rhetoric

- Jeansonne, Glen (1988). "Goldbugs, Silverites, and Satirists: Caricature and Humor in the Presidential Election of 1896". Journal of American Culture 11 (2): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1988.1102_1.x.

- Jensen, Richard J. (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict 1888–1896. ISBN 0-226-39825-0.

- Jones, Stanley L. (1964). The Presidential Election of 1896. ISBN 0-299-03094-6.

- Kazin, Michael. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (2006).

- Kelly, Patrick J. (2003). "The Election of 1896 and the Restructuring of Civil War Memory". Civil War History 49 (3): 254. doi:10.1353/cwh.2003.0058.

- Mahan, Russell L. (2003). "William Jennings Bryan and the Presidential Campaign of 1896". White House Studies 3 (1): 41.

- Morgan, H. Wayne (2004). William McKinley and His America. Kent State U. P. pp. ch 10–11. ISBN 9780873387651.

- Rove, Carl (2015-11-24). The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781476752952.

- Stonecash, Jeffrey M.; Silina, Everita. "The 1896 Realignment," American Politics Research, (Jan 2005) 33#1 pp 3–32

- Wanat, John and Karen Burke, "Estimating the Degree of Mobilization and Conversion in the 1890s: An Inquiry into the Nature of Electoral Change," American Political Science Review, (1982) 76#2 pp 360–370 in JSTOR

- Wells, Wyatt. Rhetoric of the standards: The debate over gold and silver in the 1890s," Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2015). 14#1 pp 49-68.

- Williams, R. Hal (1978). Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890s.

- Williams, R. Hal. (2010) Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896 (University Press of Kansas) 250 pp

Primary sources

- Bryan, William Jennings. The First Battle: A Story of the Campaign of 1896 (1897), speeches from 1896 campaign.

- National Democratic Committee (1896). Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party. National Democratic committee.

- This is the handbook of the Gold Democrats and strongly opposed Bryan.

- Chandler, William E. (August 1896). "Issues and Prospects of the Campaign". North American Review 163 (2): 171–182.

- Quincy, Josiah (August 1896). "Issues and Prospects of the Campaign". North American Review 163 (2): 182–195.

External links

- Presidential Election of 1896: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1896 popular vote by counties

- How close was the 1896 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- McKinley & Hobart campaign handkerchief in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database

- Election of 1896 in Counting the Votes

Navigation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||