Eigendecomposition of a matrix

In the mathematical discipline of linear algebra, eigendecomposition or sometimes spectral decomposition is the factorization of a matrix into a canonical form, whereby the matrix is represented in terms of its eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Only diagonalizable matrices can be factorized in this way.

Fundamental theory of matrix eigenvectors and eigenvalues

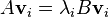

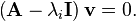

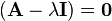

A (non-zero) vector v of dimension N is an eigenvector of a square (N×N) matrix A if and only if it satisfies the linear equation

where λ is a scalar, termed the eigenvalue corresponding to v. That is, the eigenvectors are the vectors that the linear transformation A merely elongates or shrinks, and the amount that they elongate/shrink by is the eigenvalue. The above equation is called the eigenvalue equation or the eigenvalue problem.

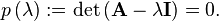

This yields an equation for the eigenvalues

We call p(λ) the characteristic polynomial, and the equation, called the characteristic equation, is an Nth order polynomial equation in the unknown λ. This equation will have Nλ distinct solutions, where 1 ≤ Nλ ≤ N . The set of solutions, that is, the eigenvalues, is called the spectrum of A.[1][2][3]

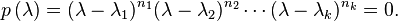

We can factor p as

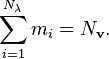

The integer ni is termed the algebraic multiplicity of eigenvalue λi. The algebraic multiplicities sum to N:

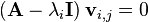

For each eigenvalue, λi, we have a specific eigenvalue equation

There will be 1 ≤ mi ≤ ni linearly independent solutions to each eigenvalue equation. The mi solutions are the eigenvectors associated with the eigenvalue λi. The integer mi is termed the geometric multiplicity of λi. It is important to keep in mind that the algebraic multiplicity ni and geometric multiplicity mi may or may not be equal, but we always have mi ≤ ni. The simplest case is of course when mi = ni = 1. The total number of linearly independent eigenvectors, Nv, can be calculated by summing the geometric multiplicities

The eigenvectors can be indexed by eigenvalues, i.e. using a double index, with vi,j being the jth eigenvector for the ith eigenvalue. The eigenvectors can also be indexed using the simpler notation of a single index vk, with k = 1, 2, ..., Nv.

Eigendecomposition of a matrix

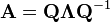

Let A be a square (N×N) matrix with N linearly independent eigenvectors,  Then A can be factorized as

Then A can be factorized as

where Q is the square (N×N) matrix whose ith column is the eigenvector  of A and Λ is the diagonal matrix whose diagonal elements are the corresponding eigenvalues, i.e.,

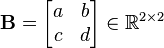

of A and Λ is the diagonal matrix whose diagonal elements are the corresponding eigenvalues, i.e.,  . Note that only diagonalizable matrices can be factorized in this way. For example, the defective matrix

. Note that only diagonalizable matrices can be factorized in this way. For example, the defective matrix  cannot be diagonalized.

cannot be diagonalized.

The eigenvectors  are usually normalized, but they need not be. A non-normalized set of eigenvectors,

are usually normalized, but they need not be. A non-normalized set of eigenvectors,  can also be used as the columns of Q. That can be understood by noting that the magnitude of the eigenvectors in Q gets canceled in the decomposition by the presence of Q−1.

can also be used as the columns of Q. That can be understood by noting that the magnitude of the eigenvectors in Q gets canceled in the decomposition by the presence of Q−1.

Example

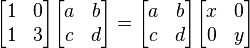

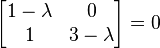

Taking a 2 × 2 real matrix  as an example to be decomposed into a diagonal matrix through multiplication of a non-singular matrix

as an example to be decomposed into a diagonal matrix through multiplication of a non-singular matrix  .

.

Then

-

, for some real diagonal matrix

, for some real diagonal matrix  .

.

Shifting  to the right hand side:

to the right hand side:

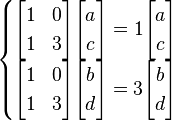

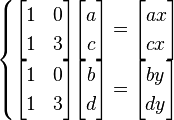

The above equation can be decomposed into 2 simultaneous equations:

Factoring out the eigenvalues  and

and  :

:

Letting  , this gives us two vector equations:

, this gives us two vector equations:

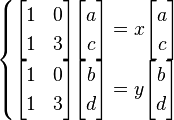

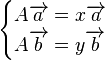

And can be represented by a single vector equation involving 2 solutions as eigenvalues:

where  represents the two eigenvalues

represents the two eigenvalues  and

and  ,

,  represents the vectors

represents the vectors  and

and  .

.

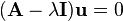

Shifting  to the left hand side and factorizing

to the left hand side and factorizing  out

out

Since  is non-singular, it is essential that

is non-singular, it is essential that  is non-zero. Therefore,

is non-zero. Therefore,

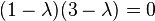

Considering the determinant of  ,

,

Thus

Giving us the solutions of the eigenvalues for the matrix  as

as  or

or  , and the resulting diagonal matrix from the eigendecomposition of

, and the resulting diagonal matrix from the eigendecomposition of  is thus

is thus  .

.

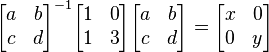

Putting the solutions back into the above simultaneous equations

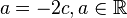

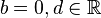

Solving the equations, we have  and

and

Thus the matrix  required for the eigendecomposition of

required for the eigendecomposition of  is

is ![\begin{bmatrix} -2c & 0 \\ c & d \end{bmatrix}, [c, d]\in \mathbb{R}](../I/m/eb321330e298946c90680fd18c583ca2.png) . i.e. :

. i.e. :

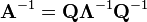

Matrix inverse via eigendecomposition

If matrix A can be eigendecomposed and if none of its eigenvalues are zero, then A is nonsingular and its inverse is given by

Furthermore, because Λ is a diagonal matrix, its inverse is easy to calculate:

Practical implications[4]

When eigendecomposition is used on a matrix of measured, real data, the inverse may be less valid when all eigenvalues are used unmodified in the form above. This is because as eigenvalues become relatively small, their contribution to the inversion is large. Those near zero or at the "noise" of the measurement system will have undue influence and could hamper solutions (detection) using the inverse.

Two mitigations have been proposed: 1) truncating small/zero eigenvalues, 2) extending the lowest reliable eigenvalue to those below it.

The first mitigation method is similar to a sparse sample of the original matrix, removing components that are not considered valuable. However, if the solution or detection process is near the noise level, truncating may remove components that influence the desired solution.

The second mitigation extends the eigenvalue so that lower values have much less influence over inversion, but do still contribute, such that solutions near the noise will still be found.

The reliable eigenvalue can be found by assuming that eigenvalues of extremely similar and low value are a good representation of measurement noise (which is assumed low for most systems).

If the eigenvalues are rank-sorted by value, then the reliable eigenvalue can be found by minimization of the Laplacian of the sorted eigenvalues:[5]

where the eigenvalues are subscripted with an 's' to denote being sorted. The position of the minimization is the lowest reliable eigenvalue. In measurement systems, the square root of this reliable eigenvalue is the average noise over the components of the system.

Functional calculus

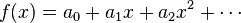

The eigendecomposition allows for much easier computation of power series of matrices. If f(x) is given by

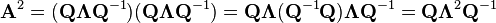

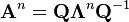

then we know that

Because Λ is a diagonal matrix, functions of Λ are very easy to calculate:

The off-diagonal elements of f(Λ) are zero; that is, f(Λ) is also a diagonal matrix. Therefore, calculating f(A) reduces to just calculating the function on each of the eigenvalues .

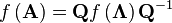

A similar technique works more generally with the holomorphic functional calculus, using

from above. Once again, we find that

Examples

Decomposition for special matrices

Normal matrices

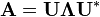

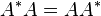

A complex normal matrix ( ) has an orthogonal eigenvector basis, so a normal matrix can be decomposed as

) has an orthogonal eigenvector basis, so a normal matrix can be decomposed as

where U is a unitary matrix. Further, if A is Hermitian ( ), which implies that it is also complex normal, the diagonal matrix Λ has only real values, and if A is unitary, Λ takes all its values on the complex unit circle.

), which implies that it is also complex normal, the diagonal matrix Λ has only real values, and if A is unitary, Λ takes all its values on the complex unit circle.

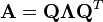

Real symmetric matrices

As a special case, for every N×N real symmetric matrix, the eigenvalues are real and the eigenvectors can be chosen such that they orthogonal to each other. Thus a real symmetric matrix A can be decomposed as

where Q is an orthogonal matrix, and Λ is a diagonal matrix whose entries are the eigenvalues of A.

Useful facts

Useful facts regarding eigenvalues

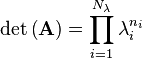

- The product of the eigenvalues is equal to the determinant of A

Note that each eigenvalue is raised to the power ni, the algebraic multiplicity.

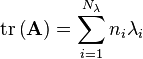

- The sum of the eigenvalues is equal to the trace of A

Note that each eigenvalue is multiplied by ni, the algebraic multiplicity.

- If the eigenvalues of A are λi, and A is invertible, then the eigenvalues of A−1 are simply λi−1.

- If the eigenvalues of A are λi, then the eigenvalues of f(A) are simply f(λi), for any holomorphic function f.

Useful facts regarding eigenvectors

- If A is Hermitian and full-rank, the basis of eigenvectors may be chosen to be mutually orthogonal. The eigenvalues are real.

- The eigenvectors of A−1 are the same as the eigenvectors of A.

- Eigenvectors are defined up to a phase, i.e. if

then

then  is also an eigenvector, and specifically so is

is also an eigenvector, and specifically so is  .

. - In the case of degenerate eigenvalues (an eigenvalue appearing more than once), the eigenvectors have an additional freedom of rotation, i.e. any linear (orthonormal) combination of eigenvectors sharing an eigenvalue (i.e. in the degenerate sub-space), are themselves eigenvectors (i.e. in the subspace).

Useful facts regarding eigendecomposition

- A can be eigendecomposed if and only if

- If p(λ) has no repeated roots, i.e. Nλ = N, then A can be eigendecomposed.

- The statement "A can be eigendecomposed" does not imply that A has an inverse.

- The statement "A has an inverse" does not imply that A can be eigendecomposed.

Useful facts regarding matrix inverse

can be inverted if and only if

can be inverted if and only if

- If

and

and  , the inverse is given by

, the inverse is given by

Numerical computations

Numerical computation of eigenvalues

Suppose that we want to compute the eigenvalues of a given matrix. If the matrix is small, we can compute them symbolically using the characteristic polynomial. However, this is often impossible for larger matrices, in which case we must use a numerical method.

In practice, eigenvalues of large matrices are not computed using the characteristic polynomial. Computing the polynomial becomes expensive in itself, and exact (symbolic) roots of a high-degree polynomial can be difficult to compute and express: the Abel–Ruffini theorem implies that the roots of high-degree (5 or above) polynomials cannot in general be expressed simply using nth roots. Therefore, general algorithms to find eigenvectors and eigenvalues are iterative.

Iterative numerical algorithms for approximating roots of polynomials exist, such as Newton's method, but in general it is impractical to compute the characteristic polynomial and then apply these methods. One reason is that small round-off errors in the coefficients of the characteristic polynomial can lead to large errors in the eigenvalues and eigenvectors: the roots are an extremely ill-conditioned function of the coefficients.[6]

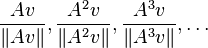

A simple and accurate iterative method is the power method: a random vector  is chosen and a sequence of unit vectors is computed as

is chosen and a sequence of unit vectors is computed as

This sequence will almost always converge to an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue of greatest magnitude, provided that v has a nonzero component of this eigenvector in the eigenvector basis (and also provided that there is only one eigenvalue of greatest magnitude). This simple algorithm is useful in some practical applications; for example, Google uses it to calculate the page rank of documents in their search engine.[7] Also, the power method is the starting point for many more sophisticated algorithms. For instance, by keeping not just the last vector in the sequence, but instead looking at the span of all the vectors in the sequence, one can get a better (faster converging) approximation for the eigenvector, and this idea is the basis of Arnoldi iteration.[6] Alternatively, the important QR algorithm is also based on a subtle transformation of a power method.[6]

Numerical computation of eigenvectors

Once the eigenvalues are computed, the eigenvectors could be calculated by solving the equation

using Gaussian elimination or any other method for solving matrix equations.

However, in practical large-scale eigenvalue methods, the eigenvectors are usually computed in other ways, as a byproduct of the eigenvalue computation. In power iteration, for example, the eigenvector is actually computed before the eigenvalue (which is typically computed by the Rayleigh quotient of the eigenvector).[6] In the QR algorithm for a Hermitian matrix (or any normal matrix), the orthonormal eigenvectors are obtained as a product of the Q matrices from the steps in the algorithm.[6] (For more general matrices, the QR algorithm yields the Schur decomposition first, from which the eigenvectors can be obtained by a backsubstitution procedure.[8]) For Hermitian matrices, the Divide-and-conquer eigenvalue algorithm is more efficient than the QR algorithm if both eigenvectors and eigenvalues are desired.[6]

Additional topics

Generalized eigenspaces

Recall that the geometric multiplicity of an eigenvalue can be described as the dimension of the associated eigenspace, the nullspace of λI − A. The algebraic multiplicity can also be thought of as a dimension: it is the dimension of the associated generalized eigenspace (1st sense), which is the nullspace of the matrix (λI − A)k for any sufficiently large k. That is, it is the space of generalized eigenvectors (1st sense), where a generalized eigenvector is any vector which eventually becomes 0 if λI − A is applied to it enough times successively. Any eigenvector is a generalized eigenvector, and so each eigenspace is contained in the associated generalized eigenspace. This provides an easy proof that the geometric multiplicity is always less than or equal to the algebraic multiplicity.

This usage should not be confused with the generalized eigenvalue problem described below.

Conjugate eigenvector

A conjugate eigenvector or coneigenvector is a vector sent after transformation to a scalar multiple of its conjugate, where the scalar is called the conjugate eigenvalue or coneigenvalue of the linear transformation. The coneigenvectors and coneigenvalues represent essentially the same information and meaning as the regular eigenvectors and eigenvalues, but arise when an alternative coordinate system is used. The corresponding equation is

For example, in coherent electromagnetic scattering theory, the linear transformation A represents the action performed by the scattering object, and the eigenvectors represent polarization states of the electromagnetic wave. In optics, the coordinate system is defined from the wave's viewpoint, known as the Forward Scattering Alignment (FSA), and gives rise to a regular eigenvalue equation, whereas in radar, the coordinate system is defined from the radar's viewpoint, known as the Back Scattering Alignment (BSA), and gives rise to a coneigenvalue equation.

Generalized eigenvalue problem

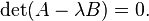

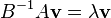

A generalized eigenvalue problem (2nd sense) is the problem of finding a vector v that obeys

where A and B are matrices. If v obeys this equation, with some λ, then we call v the generalized eigenvector of A and B (in the 2nd sense), and λ is called the generalized eigenvalue of A and B (in the 2nd sense) which corresponds to the generalized eigenvector v. The possible values of λ must obey the following equation

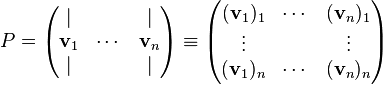

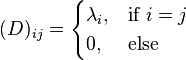

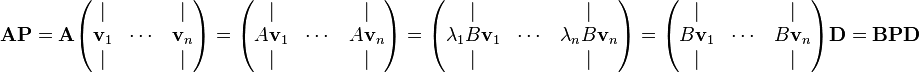

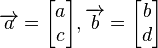

In the case we can find  linearly independent vectors

linearly independent vectors  so that for every

so that for every  ,

,  , where

, where

then we define the matrices P and D such that

then we define the matrices P and D such that

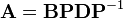

Then the following equality holds

And the proof is

And since P is invertible, we multiply the equation from the right by its inverse, finishing the proof.

The set of matrices of the form A − λB, where λ is a complex number, is called a pencil; the term matrix pencil can also refer to the pair (A,B) of matrices.[9] If B is invertible, then the original problem can be written in the form

which is a standard eigenvalue problem. However, in most situations it is preferable not to perform the inversion, but rather to solve the generalized eigenvalue problem as stated originally. This is especially important if A and B are Hermitian matrices, since in this case  is not generally Hermitian and important properties of the solution are no longer apparent.

is not generally Hermitian and important properties of the solution are no longer apparent.

If A and B are Hermitian and B is a positive-definite matrix, the eigenvalues λ are real and eigenvectors v1 and v2 with distinct eigenvalues are B-orthogonal ( ).[10] Also, in this case it is guaranteed that there exists a basis of generalized eigenvectors (it is not a defective problem).[9] This case is sometimes called a Hermitian definite pencil or definite pencil.[9]

).[10] Also, in this case it is guaranteed that there exists a basis of generalized eigenvectors (it is not a defective problem).[9] This case is sometimes called a Hermitian definite pencil or definite pencil.[9]

See also

- Matrix decomposition

- List of matrices

- Eigenvalue, eigenvector and eigenspace

- Spectral theorem

- Householder transformation

- Frobenius covariant

- Sylvester's formula

- Eigenvalue perturbation

Notes

- ↑ Golub & Van Loan (1996, p. 310)

- ↑ Kreyszig (1972, p. 273)

- ↑ Nering (1970, p. 270)

- ↑ Hayde, A. F.; Twede, D. R. (2002). Shen, Sylvia S, ed. "Observations on relationship between eigenvalues, instrument noise and detection performance". Imaging Spectrometry VIII. Edited by Shen. Imaging Spectrometry VIII 4816: 355. Bibcode:2002SPIE.4816..355H. doi:10.1117/12.453777.

- ↑ Twede, D. R.; Hayden, A. F. (2004). Shen, Sylvia S; Lewis, Paul E, eds. "Refinement and generalization of the extension method of covariance matrix inversion by regularization". Imaging Spectrometry IX. Edited by Shen. Imaging Spectrometry IX 5159: 299. Bibcode:2004SPIE.5159..299T. doi:10.1117/12.506993.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lloyd N. Trefethen; David Bau (1997). Numerical Linear Algebra. SIAM. ISBN 978-0898713619.

- ↑ Ipsen, Ilse, and Rebecca M. Wills, Analysis and Computation of Google's PageRank, 7th IMACS International Symposium on Iterative Methods in Scientific Computing, Fields Institute, Toronto, Canada, 5–8 May 2005.

- ↑ Alfio Quarteroni, Riccardo Sacco, Fausto Saleri (2000). "section 5.8.2". Numerical Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 9780387989594.

- 1 2 3 Z. Bai, J. Demmel, J. Dongarra, A. Ruhe, and H. Van Der Vorst, ed. (2000). "Generalized Hermitian Eigenvalue Problems". Templates for the Solution of Algebraic Eigenvalue Problems: A Practical Guide. Philadelphia: SIAM. ISBN 0-89871-471-0.

- ↑ Parlett, Beresford N. (1998). The symmetric eigenvalue problem (Reprint. ed.). Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-89871-402-9.

References

- Franklin, Joel N. (1968). Matrix Theory. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41179-6.

- Golub, Gene H.; Van Loan, Charles F. (1996), Matrix Computations (3rd ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5414-8

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1985). Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38632-2.

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1991). Topics in Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46713-6.

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1972), Advanced Engineering Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-50728-8

- Nering, Evar D. (1970), Linear Algebra and Matrix Theory (2nd ed.), New York: Wiley, LCCN 76091646

- Strang, G. (1998). Introduction to Linear Algebra (3rd ed.). Wellesley-Cambridge Press. ISBN 0-9614088-5-5.

![\begin{bmatrix}

-2c & 0 \\ c & d \\ \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 3 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -2c & 0 \\ c & d \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 3 \\ \end{bmatrix}, [c, d]\in \mathbb{R}](../I/m/657064ced5750d6fdc2b992ae0eeed23.png)

![\left[\Lambda^{-1}\right]_{ii}=\frac{1}{\lambda_i}](../I/m/7865280dc7d7c47ac98dc6efa8975a6b.png)

![\left[f\left(\mathbf{\Lambda}\right)\right]_{ii}=f\left(\lambda_i\right)](../I/m/c6bd5bc054691ad698a4f531cd3b32db.png)