Great Sphinx of Giza

.jpg)

The Great Sphinx of Giza (Arabic: أبو الهول Abū al-Haul, English: The Terrifying One; literally: Father of Dread), commonly referred to as the Sphinx, is a limestone statue of a reclining or couchant sphinx (a mythical creature with a lion's body and a human head) that stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, Egypt. The face of the Sphinx is generally believed to represent the face of the Pharaoh Khafra.

It is the largest monolith statue in the world, standing 73.5 metres (241 ft) long, 19.3 metres (63 ft) wide, and 20.22 m (66.34 ft) high.[1] It is the oldest known monumental sculpture, and is commonly believed to have been built by ancient Egyptians of the Old Kingdom during the reign of the Pharaoh Khafra (c. 2558–2532 BC).[1][2]

Construction

The Sphinx is a monolith carved down into the bedrock of the plateau which also served as the quarry for the pyramids and other monuments in the area. Because of its geological history, the nummulitic limestone of the area consists of layers of widely differing quality offering unequal resistance to erosion, mostly due to wind and windblown sand, which explains the uneven degradation of the body of the Sphinx. The floor of the Sphinx depression and lowest part of the body including the legs is solid, hard rock. Above this, the body of the lion up to its neck is a heterogeneous zone with friable layers that have suffered considerable disintegration. The layer in which the head was sculpted is also much harder.[3]

Origin and identity

.jpg)

The Great Sphinx is one of the world's largest and oldest statues but basic facts about it are still subject to debate, such as when it was built, by whom, and for what purpose. These questions have resulted in the popular idea of the "Riddle of the Sphinx",[4] alluding to the original Greek legend of the Riddle of the Sphinx.

Pliny the Elder mentioned the Great Sphinx in his book, Natural History, commenting that the Egyptians looked upon the statue as a "divinity" that has been passed over in silence and "that King Harmais was buried in it".[3][5]

Names of the Sphinx

It is not known by what name the creators called their statue, as the Great Sphinx does not appear in any known inscription of the Old Kingdom, and there are no inscriptions anywhere describing its construction or its original purpose. In the New Kingdom, the Sphinx was called Hor-em-akhet (English: Horus of the Horizon; Hellenized: Harmachis), and the pharaoh Thutmose IV (1401–1391 or 1397–1388 BC)[6] specifically referred to it as such in his Dream Stele.

The commonly used name Sphinx was given to it in classical antiquity, about 2000 years after the commonly accepted date of its construction, by reference to a Greek mythological beast with a lion's body, a woman's head and the wings of an eagle (although, like most Egyptian sphinxes, the Great Sphinx has a man's head and no wings). The English word sphinx comes from the ancient Greek Σφίγξ (transliterated: sphinx), apparently from the verb σφίγγω (transliterated: sphingo / English: to squeeze), after the Greek sphinx who strangled anyone who failed to answer her riddle.

The name may alternatively be a linguistic corruption of the phonetically different ancient Egyptian word Ssp-anx (in Manuel de Codage). This name is given to royal statues of the Fourth dynasty of ancient Egypt (2575–2467 BC), and later in the New Kingdom (c. 1570–1070 BC) to the Great Sphinx more specifically.

Medieval Arab writers, including al-Maqrīzī, call the Sphinx balhib and bilhaw, which suggest a Coptic influence. The modern Egyptian Arabic name is أبو الهول (Abū al Hūl, English: The Terrifying One).

Builder and timeframe

Though there have been conflicting evidence and viewpoints over the years, the view held by modern Egyptology at large remains that the Great Sphinx was built in approximately 2500 BC for the pharaoh Khafra, the builder of the Second Pyramid at Giza.[7]

Selim Hassan, writing in 1949 on recent excavations of the Sphinx enclosure, summed up the problem:

Taking all things into consideration, it seems that we must give the credit of erecting this, the world's most wonderful statue, to Khafre, but always with this reservation: that there is not one single contemporary inscription which connects the Sphinx with Khafre; so, sound as it may appear, we must treat the evidence as circumstantial, until such time as a lucky turn of the spade of the excavator will reveal to the world a definite reference to the erection of the Sphinx.[8]

The "circumstantial" evidence mentioned by Hassan includes the Sphinx's location in the context of the funerary complex surrounding the Second Pyramid, which is traditionally connected with Khafra.[9] Apart from the Causeway, the Pyramid and the Sphinx, the complex also includes the Sphinx Temple and the Valley Temple, both of which display the same architectural style, with 200-tonne stone blocks quarried out of the Sphinx enclosure.

A diorite statue of Khafre, which was discovered buried upside down along with other debris in the Valley Temple, is claimed as support for the Khafra theory.

The Dream Stele, erected much later by the pharaoh Thutmose IV (1401–1391 or 1397–1388 BC), associates the Sphinx with Khafra. When the stele was discovered, its lines of text were already damaged and incomplete, and only referred to Khaf, not Khafra. An extract was translated:

which we bring for him: oxen ... and all the young vegetables; and we shall give praise to Wenofer ... Khaf ... the statue made for Atum-Hor-em-Akhet.[10]

The Egyptologist Thomas Young, finding the Khaf hieroglyphs in a damaged cartouche used to surround a royal name, inserted the glyph ra to complete Khafra's name. When the Stele was re-excavated in 1925, the lines of text referring to Khaf flaked off and were destroyed.

Dissenting hypotheses

Theories held by academic Egyptologists regarding the builder of the Sphinx and the date of its construction are not universally accepted, and various persons have proposed various alternative hypotheses about both the builder and the dating.

Early Egyptologists

Some of the early Egyptologists and excavators of the Giza pyramid complex believed the Great Sphinx and other structures in the Sphinx enclosure predated the traditional date of construction (the reign of Khafre or Khephren, 2520–2492 BC).

In 1857, Auguste Mariette, founder of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, unearthed the much later Inventory Stela (estimated Dynasty XXVI, c. 678–525 BC), which tells how Khufu came upon the Sphinx, already buried in sand. Although certain tracts on the Stela are considered good evidence,[11] this passage is widely dismissed as Late Period historical revisionism.[12]

Gaston Maspero, the French Egyptologist and second director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, conducted a survey of the Sphinx in 1886 and concluded:

The Sphinx stela shows, in line thirteen, the cartouche of Khephren.[n 1] I believe that to indicate an excavation carried out by that prince, following which, the almost certain proof that the Sphinx was already buried in sand by the time of Khafre[n 1] and his predecessors [i.e. Dynasty IV, c. 2575–2467 BC].[13]

In 1904, English Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge wrote in The Gods of the Egyptians:

This marvelous object [the Great Sphinx] was in existence in the days of Khafre, or Khephren,[n 1] and it is probable that it is a very great deal older than his reign and that it dates from the end of the archaic period [c. 2686 BC].[14]

Modern dissenting hypotheses

Rainer Stadelmann, former director of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo, examined the distinct iconography of the nemes (headdress) and the now-detached beard of the Sphinx and concluded that the style is more indicative of the Pharaoh Khufu (2589–2566 BC), builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza and Khafra's father.[15] He supports this by suggesting that Khafra's Causeway was built to conform to a pre-existing structure, which, he concludes, given its location, could only have been the Sphinx.[12]

Colin Reader, an English geologist who independently conducted a more recent survey of the enclosure, agrees that the various quarries on the site have been excavated around the Causeway. Because these quarries are known to have been used by Khufu, Reader concludes that the Causeway (and the temples on either end thereof) must predate Khufu, thereby casting doubt on the conventional Egyptian chronology.[12]

In 2004, Vassil Dobrev of the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale in Cairo announced that he had uncovered new evidence that the Great Sphinx may have been the work of the little-known Pharaoh Djedefre (2528–2520 BC), Khafra's half brother and a son of Khufu.[16] Dobrev suggests that Djedefre built the Sphinx in the image of his father Khufu, identifying him with the sun god Ra in order to restore respect for their dynasty. Dobrev also notes, like Stadelmann and others, that the causeway connecting Khafre's pyramid to the temples was built around the Sphinx suggesting it was already in existence at the time.[15]

Fringe hypotheses

Orion correlation theory

The Orion correlation theory, as expounded by popular authors Graham Hancock and Robert Bauval,[17] is based on the proposed exact correlation of the three pyramids at Giza with the three stars ζ Ori, ε Ori and δ Ori, the stars forming Orion's Belt, in the relative positions occupied by these stars in 10500 BC. The authors argue that the geographic relationship of the Sphinx, the Giza pyramids and the Nile directly corresponds with Leo, Orion and the Milky Way respectively. Sometimes cited as an example of pseudoarchaeology, the theory is at variance with mainstream scholarship.[18][19][20]

Water erosion hypothesis

The Sphinx water erosion hypothesis contends that the main type of weathering evident on the enclosure walls of the Great Sphinx could only have been caused by prolonged and extensive rainfall,[21] and that it must therefore predate the time of the pharaoh Khafra. The hypothesis is championed primarily by Robert M. Schoch, a geologist and associate professor of natural science at the College of General Studies at Boston University, and John Anthony West, an author and alternative Egyptologist.

At the behest of West, Frank Domingo, a forensic scientist in the New York City Police Department and an expert forensic anthropologist,[22] used detailed measurements of the Sphinx, forensic drawings and computer imaging to conclude that Khafra, as depicted on extant statuary, was not the model for the Sphinx's face.[23]

The Great Sphinx as Anubis

Author Robert K. G. Temple proposes that the Sphinx was originally a statue of the Jackal-Dog Anubis, the God of the Necropolis, and that its face was recarved in the likeness of a Middle Kingdom pharaoh, Amenemhet II. Temple bases his identification on the style of the eye make-up and the style of the pleats on the head-dress.[24]

Racial characteristics

Over the years several authors have commented on what they perceive as "Negroid" characteristics in the face of the Sphinx.[25] This issue has become part of the Ancient Egyptian race controversy, with respect to the ancient population as a whole.[26] The face of the Sphinx has been damaged over the millennia.

Medical analysis

Surgeon Hutan Ashrafian from Imperial College London has analysed the Sphinx to identify that it may have represented an individual suffering from prognathism which may have been a reflection of a disease suffered by the sculpture’s human inspiration. Furthermore, as the Sphinx represented a lion, the same person may have suffered from an associated condition where "lion-like" features were apparent (leontiasis ossea).[27][28]

Restoration

After the Giza Necropolis was abandoned, the Sphinx became buried up to its shoulders in sand. The first documented attempt at an excavation dates to c. 1400 BC, when the young Thutmose IV (1401–1391 or 1397–1388 BC) gathered a team and, after much effort, managed to dig out the front paws, between which he placed a granite slab, known as the Dream Stele, inscribed with the following (an extract):

... the royal son, Thothmos, being arrived, while walking at midday and seating himself under the shadow of this mighty god, was overcome by slumber and slept at the very moment when Ra is at the summit [of heaven]. He found that the Majesty of this august god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks to his son, saying: Look upon me, contemplate me, O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living ... Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.[29]

Later, Ramesses II the Great (1279–1213 BC) may have undertaken a second excavation.

Mark Lehner, an Egyptologist, originally asserted that there had been a far earlier renovation during the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2184 BC),[30] although he has subsequently recanted this "heretical" viewpoint.[31]

In AD 1817, the first modern archaeological dig, supervised by the Italian Captain Giovanni Battista Caviglia, uncovered the Sphinx's chest completely. The entire Sphinx was finally excavated in 1925 to 1936, in digs led by Émile Baraize.

In 1931, engineers of the Egyptian government repaired the head of the Sphinx because part of its headdress had fallen off in 1926 due to erosion, which had also cut deeply into its neck.[32]

Missing nose and beard

The one-metre-wide nose on the face is missing. Examination of the Sphinx's face shows that long rods or chisels were hammered into the nose, one down from the bridge and one beneath the nostril, then used to pry the nose off towards the south.[34]

The Arab historian al-Maqrīzī, writing in the 15th century, attributes the loss of the nose to iconoclasm by Muhammad Sa'im al-Dahr, a Sufi Muslim from the khanqah of Sa'id al-Su'ada. In AD 1378, upon finding the local peasants making offerings to the Sphinx in the hope of increasing their harvest. Enraged, he destroyed the nose, and was later hanged for vandalism.[35] Al-Maqrīzī describes the Sphinx as the "talisman of the Nile" on which the locals believed the flood cycle depended.

There is also a story that the nose was broken off by a cannonball fired by Napoleon's soldiers, that still lives on today. Other variants indict British troops, the Mamluks, and others. Sketches of the Sphinx by the Dane Frederic Louis Norden, made in 1738 and published in 1757, show the Sphinx missing its nose.[36] This predates Napoleon's birth in 1769.

In addition to the lost nose, a ceremonial pharaonic beard is thought to have been attached, although this may have been added in later periods after the original construction. Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev has suggested that had the beard been an original part of the Sphinx, it would have damaged the chin of the statue upon falling.[15] The lack of visible damage supports his theory that the beard was a later addition.

Mythology

Colin Reader has proposed that the Sphinx was probably the focus of solar worship in the Early Dynastic Period, before the Giza Plateau became a necropolis in the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2134 BC).[37] He ties this in with his conclusions that the Sphinx, the Sphinx temple, the Causeway and the Khafra mortuary temple are all part of a complex which predates Dynasty IV (c. 2613–2494 BC). The lion has long been a symbol associated with the sun in ancient Near Eastern civilizations. Images depicting the Egyptian king in the form of a lion smiting his enemies date as far back as the Early Dynastic Period.

In the New Kingdom, the Sphinx became more specifically associated with the god Hor-em-akhet (Hellenized: Harmachis) or "Horus-at-the-Horizon", which represented the pharaoh in his role as the Shesep-ankh (English: Living Image) of the god Atum. Pharaoh Amenhotep II (1427–1401 or 1397 BC) built a temple to the north east of the Sphinx nearly 1000 years after its construction, and dedicated it to the cult of Hor-em-akhet.

Reception

In the last 700 years, there has been a proliferation of travellers and reports from Lower Egypt, unlike Upper Egypt, which was seldom reported from prior to the mid-18th century. Alexandria, Rosetta, Damietta, Cairo and the Giza Pyramids are described repeatedly, but not necessarily comprehensively. Many accounts were published and widely read. These include those of George Sandys, André Thévet, Athanasius Kircher, Balthasar de Monconys, Jean de Thévenot, John Greaves, Johann Michael Vansleb, Benoît de Maillet, Cornelis de Bruijn, Paul Lucas, Richard Pococke, Frederic Louis Norden and others. But there is an even larger set of more anonymous people who wrote obscure and little-read works, sometimes only unpublished manuscripts in libraries or private collections, including Henry Castela, Hans Ludwig von Lichtenstein, Michael Heberer von Bretten, Wilhelm von Boldensele, Pierre Belon du Mans, Vincent Stochove, Christophe Harant, Gilles Fermanel, Robert Fauvel, Jean Palerne Foresien, Willian Lithgow, Joos van Ghistele, etc.

Over the centuries, writers and scholars have recorded their impressions and reactions upon seeing the Sphinx. The vast majority were concerned with a general description, often including a mixture of science, romance and mystique. A typical description of the Sphinx by tourists and leisure travelers throughout the 19th and 20th century was made by John Lawson Stoddard:

It is the antiquity of the Sphinx which thrills us as we look upon it, for in itself it has no charms. The desert's waves have risen to its breast, as if to wrap the monster in a winding-sheet of gold. The face and head have been mutilated by Moslem fanatics. The mouth, the beauty of whose lips was once admired, is now expressionless. Yet grand in its loneliness, – veiled in the mystery of unnamed ages, – the relic of Egyptian antiquity stands solemn and silent in the presence of the awful desert – symbol of eternity. Here it disputes with Time the empire of the past; forever gazing on and on into a future which will still be distant when we, like all who have preceded us and looked upon its face, have lived our little lives and disappeared.[38]

From the 16th century far into the 19th century, observers repeatedly noted that the Sphinx has the face, neck and breast of a woman. Examples included Johannes Helferich (1579), George Sandys (1615), Johann Michael Vansleb (1677), Benoît de Maillet (1735) and Elliot Warburton (1844).

Most early Western images were book illustrations in print form, elaborated by a professional engraver from either previous images available or some original drawing or sketch supplied by an author, and usually now lost. Seven years after visiting Giza, André Thévet (Cosmographie de Levant, 1556) described the Sphinx as "the head of a colossus, caused to be made by Isis, daughter of Inachus, then so beloved of Jupiter". He, or his artist and engraver, pictured it as a curly-haired monster with a grassy dog collar. Athanasius Kircher (who never visited Egypt) depicted the Sphinx as a Roman statue, reflecting his ability to conceptualize (Turris Babel, 1679). Johannes Helferich's (1579) Sphinx is a pinched-face, round-breasted woman with a straight haired wig; the only edge over Thevet is that the hair suggests the flaring lappets of the headdress. George Sandys stated that the Sphinx was a harlot; Balthasar de Monconys interpreted the headdress as a kind of hairnet, while François de La Boullaye-Le Gouz's Sphinx had a rounded hairdo with bulky collar.

Richard Pococke's Sphinx was an adoption of Cornelis de Bruijn's drawing of 1698, featuring only minor changes, but is closer to the actual appearance of the Sphinx than anything previous. The print versions of Norden's careful drawings for his Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie, 1755 are the first to clearly show that the nose was missing. However, from the time of the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt onwards, a number of accurate images were widely available in Europe, and copied by others.

Legacy

In media

Mystery of the Sphinx, narrated by Charlton Heston, a documentary presenting the theories of John Anthony West, was shown as an NBC Special on 10 November 1993 (winning an Emmy award for Best Research) A 95-minute DVD, Mystery of the Sphinx: Expanded Edition was released in 2007.[39] Age of the Sphinx, a BBC Two Timewatch documentary presenting the theories of John Anthony West and critical to both sides of the argument, was shown on 27 November 1994. In 2008, the film 10,000 BC showed a supposed original Sphinx with a lion's head. Before this film, this lion head theory had been published in documentary films about the origin of the Sphinx.

In popular culture

Several fictional stories pose some comedic causes of the Sphinx's facial deformity. Disney's cartoon film Aladdin (1992) attributes the Sphinx's broken nose to a stonemason who accidentally chipped it off after being distracted by Aladdin and Jasmine flying past on their magic carpet during the song "A Whole New World". In the cartoon book Asterix and Cleopatra, Obelix climbs up the face of the Sphinx and accidentally knocks the nose off. An episode of the Disney television series Ducktales shows the Sphinx nose being destroyed moments after its completion when Bubba the Caveduck accidentally crashes into it with a time machine.

Gallery

-

André Thévet, Cosmographie de Levant (1556)

-

Hogenberg and Braun (map), Cairus, quae olim Babylon (1572), exists in various editions, from various authors, with the Sphinx looking different.

-

Jan Sommer, (unpublished) Voyages en Egypte des annees 1589, 1590 & 1591, Institut de France, 1971 (Voyageurs occidentaux en Égypte 3)

-

George Sandys, A relation of a journey begun an dom. 1610 (1615)

-

François de La Boullaye-Le Gouz, Les Voyages et Observations (1653)

-

Balthasar de Monconys, Journal des voyages (1665)

-

Olfert Dapper, Description de l'Afrique (1665), note the two different displays of the Sphinx.

-

Cornelis de Bruijn, Reizen van Cornelis de Bruyn door de vermaardste Deelen van Klein Asia (1698)

-

.png)

The Sphinx as seen by Frederic Louis Norden (1755)

-

.png)

Frederic Louis Norden, Voyage d'Égypte et de Nubie (1755)

-

.png)

Description de l'Egypte (Panckoucke edition), Planches, Antiquités, volume V (1823), also published in the Imperial edition of 1822.

-

.png)

Description de l'Egypte (Panckoucke edition), Planches, Antiquités, volume V (1823), also published in the Imperial edition of 1822.

-

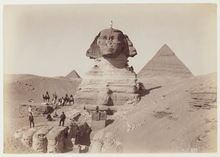

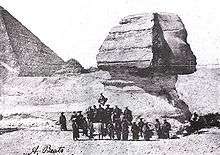

Members of the Second Japanese Embassy to Europe (1863) in front of the Sphinx, 1864.

-

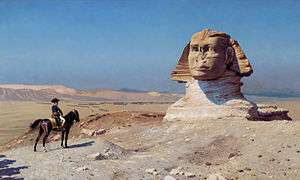

Jean-Léon Gérôme's Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, 1867–1868.

-

Johanne Baptista Homann (map), Aegyptus hodierna (1724)

-

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt. Gizeh [selected images]. View 04: Pyramids and Sphinx., n.d., Kay C. Lenskold. Floral Park, N.Y. Brooklyn Museum Archives

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Emporis – Great Sphinx of Giza". Giza /: Emporis.com. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ↑ Dunford, Jane; Fletcher, Joann; French, Carole (ed., 2007). Egypt: Eyewitness Travel Guide. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7566-2875-8.

- 1 2 Christiane Zivie-Coche, Sphinx: History of a Monument, pages 99–100 (Cornell University Press, 2002). ISBN 0-8014-3962-0

- ↑ Coxill, David (1998). "The Riddle of the Sphinx". InScription: Journal of Ancient Egypt. 2 (Spring 1998), 17; cited in Schoch, Robert M. (2000). "New Studies Confirm Very Old Sphinx" in Dowell, Colette M. (ed). Circular Times.

- ↑ "The Natural History of Pliny : Pliny, the Elder". Book 36. Translation by John Bostock and Henry Thomas Riley. London: H. G. Bohn. 1857. p. 336–337. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ See Thutmose IV#Dates and length of reign

- ↑ "Sphinx Project: Why Sequence is Important". 2007. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ Hassan, Selim (1949). The Sphinx: Its history in the light of recent excavations. Cairo: Government Press, 1949.

- ↑ Lehner, Mark (Spring 2002). "Unfinished Business: The Great Sphinx" in Aeragram, 5:2 (Spring 2002), 10–14. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ↑ Colavito, Jason (2001). "Who Built the Sphinx?" at Lost Civilizations Discovered. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ↑ Hawass, Zahi. (The Khufu at The Plateau. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 Reader, Colin (2002). "Giza Before the Fourth Dynasty", Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum, 9 (2002), 5–21. Retrieved 2008-12-17. Archived December 10, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Giza Sphinx & Temples Page 3 - The Great Sphinx - Spirit & Stone". Theglobaleducationproject.org. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ↑ Wallis Budge, E. A. (1904). The Gods of the Egyptians: Studies in Egyptian Mythology. Courier Dover Publications, 1969. 2 volumes. ISBN 0-486-22055-9.

- 1 2 3 Fleming, Nic (2004-12-14). "I have solved riddle of the Sphinx, says Frenchman" in The Daily Telegraph. Updated 14 December 2004. Retrieved 28 June 2005.

- ↑ Riddle of the Sphinx Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ↑ Hancock, Graham; Bauval, Robert (2000-12-14). Atlantis Reborn Again. Horizon. BBC. Aired 2000-12-14.

- ↑ Orser, Charles E. (2003). Race and practice in archaeological interpretation. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8122-3750-4.

- ↑ Hancock, Graham; Bauval, Robert (1997). The Message of the Sphinx: A Quest for the Hidden Legacy of Mankind. Three Rivers Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-517-88852-0.

- ↑ Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.) (2006). Archaeological fantasies: how pseudoarchaeology misrepresents the past and misleads the public. Routledge. pp. 20, 38–40, 100–103, 127, 197–201, 238, 241–255. ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8.

- ↑ Schoch, Robert M. (1992). "Redating the Great Sphinx of Giza" in Circular Times, ed. Collette M. Dowell. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ↑ Taylor, Karen T., History of the IAI Forensic Art Discipline at the International Association for Identification. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ↑ West, John Anthony (1993). Serpent in the Sky: The High Wisdom of Ancient Egypt, 232. Wheaton: Quest Books, 1993. ISBN 0-8356-0691-0.

- ↑ Robert K. G. Temple, The Sphinx Mystery: The Forgotten Origins of The Sanctuary of Anubis (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2009). ISBN 978-1-59477-271-9

- ↑ Regier, Willis G. (ed.) (2004). Book of the Sphinx. U of Nebraska Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8032-3956-2.

- ↑ Irwin, Graham W. (1977). Africans abroad, Columbia University Press, p. 11

- ↑ Ashrafian, Hutan. (2005). "The medical riddle of the Great Sphinx of Giza". J Endocrinol Invest 28: 866. doi:10.1007/bf03347583.

- ↑ Galassi, Francesco M. (2014). "On the face and identity of the Great Sphinx of Giza: a medico-anthropological review". Shemu (the quarterly newsletter of the Egyptian Society of South Africa) 18 (3).

- ↑ Mallet, Dominique, The Stele of Thothmes IV: A Translation, at harmakhis.org. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ "The ARCE Sphinx Project—A Preliminary Report". Hall of Maat. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ "'Khufu Knew the Sphinx' by Colin Reader". Ianlawton.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Popular Science Monthly, July 1931, page 56.

- ↑ "British Museum - Fragment of the beard of the Great Sphinx". britishmuseum.org.

- ↑ Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids. Thames & Hudson. p. 41. ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- ↑ "Faq#11: Who shot off the nose of the Sphinx?". napoleon-series.org. Retrieved February 2012.

- ↑ "F.L. Norden. Travels in Egypt and Nubia, 1757. Plate 47, Profil de la tête colossale du Sphinx". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 24 Jan 2014.

- ↑ Reader, Colin (2000-03-17). Further considerations on the Age of the Sphinx at Rational Spirituality. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ "John L. Stoddard's Lectures" 2. 1898: 111.

- ↑ Blueghost (10 November 1993). "Mystery of the Sphinx (TV Movie 1993)". IMDb.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Sphinx of Giza. |

- Riddle of the Sphinx

- Egyptian and Greek Sphinxes

- Egypt—The Lost Civilization Theory

- The Sphinx's Nose

- What happened to the Sphinx's nose?

- Sphinx photo gallery

- Al Maqrizi's account (Arabic)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

Coordinates: 29°58′31″N 31°08′16″E / 29.97528°N 31.13778°E