Edwards curve

In mathematics, the Edwards curves are a family of elliptic curves studied by Harold Edwards in 2007. The concept of elliptic curves over finite fields is widely used in elliptic curve cryptography. Applications of Edwards curves to cryptography were developed by Bernstein and Lange: they pointed out several advantages of the Edwards form in comparison to the more well known Weierstrass form.

Definition

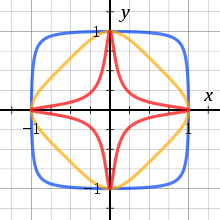

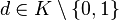

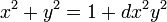

The equation of an Edwards curve over a field K which does not have characteristic 2 is:

for some scalar  .

Also the following form with parameters c and d is called an Edwards curve:

.

Also the following form with parameters c and d is called an Edwards curve:

where c, d ∈ K with cd(1 − c4·d) ≠ 0.

Every Edwards curve is birationally equivalent to an elliptic curve in Weierstrass form, and thus admits an algebraic group law once one chooses a point to serve as a neutral element. If K is finite, then a sizeable fraction of all elliptic curves over K can be written as Edwards curves. Often elliptic curves in Edwards form are defined having c=1, without loss of generality. In the following sections, it is assumed that c=1.

The group law

(See also Weierstrass curve group law)

The points on an elliptic curve form an abelian group: one can add points and take integer multiples of a single point. When an elliptic curve is described by a non-singular cubic equation, then the sum of two points P and Q, denoted P + Q, is directly related to third point of intersection between the curve and the line that passes through P and Q. But for higher degree singular curves, such as Edwards curves, the situation is somewhat more complicated. For a geometric explanation of the addition law on Edwards curves, see "Faster Computation of the Tate Pairing" by Arene et al.[1]

Edwards addition law

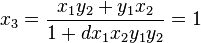

On any elliptic curve, by which is meant a curve of genus 1 and a point selected to serve the neutral element, the sum of two points is given by a rational expression of the coordinates of the points, although in general one may need to use several formulas to cover all possible pairs. For the Edwards curve, taking the neutral element to be the point (0, 1), the sum of the points (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) is given by the formula

The inverse of any point (x1, y1) is (−x1, y1). One can check that the point (0, −1) has order 2, and that the points (±1,0) have order 4. In particular, an Edwards curve always has a point of order 4 with coordinates in K.

If d is not a square in K, then there are no exceptional points: the denominators 1 + dx1x2y1y2 and 1 − dx1x2y1y2 are always nonzero. Therefore, the Edwards addition law is complete when d is not a square in K. This means that the formulas work for all pairs of input points on the Edwards curve with no exceptions for doubling, no exception for the neutral element, no exception for negatives, etc.[2] In other words, it is defined for all pairs of input points on the Edwards curve over K and the result gives the sum of the input points.

If d is a square in K, then the same operation can have exceptional points, i.e. there can be pairs (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) where 1 + dx1x2y1y2 = 0 or 1 − dx1x2y1y2 = 0.

One of the attractive feature of the Edwards Addition law is that it is strongly unified i.e. it can also be used to double a point, simplifying protection against side-channel attack. The addition formula above is faster than other unified formulas and has the strong property of completeness[2]

Example of addition law :

Let's consider the elliptic curve in the Edwards form with d=2

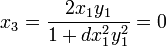

and the point  on it. It is possible to prove that the sum of P1 with the neutral element (0,1) gives again P1. Indeed, using the formula given above, the coordinates of the point given by this sum are:

on it. It is possible to prove that the sum of P1 with the neutral element (0,1) gives again P1. Indeed, using the formula given above, the coordinates of the point given by this sum are:

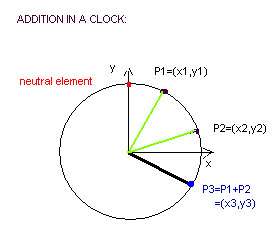

An analogue on the circle

To understand better the concept of "addition" of points on a curve, a nice example is given by the classical circle group:

take the circle of radius 1

and consider two points P1=(x1,y1), P2=(x2,y2) on it. Let α1 and α2 be the angles such that:

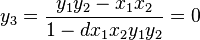

The sum of P1 and P2 is, thus, given by the sum of "their angles". That is, the point P3=P1+P2 is a point on the circle with coordinates (x3,y3), where:

In this way, the addition formula for points on the circle of radius 1 is:

.

.

Projective homogeneous coordinates

In the context of cryptography, homogeneous coordinates are used to prevent field inversions that appear in the affine formula. To avoid inversions in the original Edwards addition formulas, the curve equation can be written in projective coordinates as:

.

.

A projective point (X1 : Y1 : Z1) corresponds to the affine point (X1/Z1, Y1/Z1) on the Edwards curve.

The identity element is represented by (0 : 1 : 1). The inverse of (X1 : Y1 : Z1) is (−X1 : Y1 : Z1).

An addition formula in projective homogeneous coordinates is given by:

- (X3 : Y3 : Z3) = (X1 : Y1 : Z1) + (X2 : Y2 : Z2)

where

- X3 = Z1Z2(X1Y2 − Y1X2)(X1Y1Z22 + Z12X2Y2)

- Y3 = Z1Z2(X1X2 + Y1Y2)(X1Y1Z22 − Z12X2Y2)

- Z3 = kZ12Z22(X1X2 + Y1Y2)(X1Y2 − Y1X2) with k = 1/c.

Algorithm

Using the following algorithm, X3, Y3, Z3 can be written as: X3→ GJ, Y3→ HK, Z3→ kJK.d

where: A→ X1Z2,

B→ Y1Z2,

C→ Z1X2,

D→ Z1Y2,

E→ AB,

F→ CD,

G→ E+F,

H→ E-F,

J→ (A-C)(B+D)-H,

K→ (A+D)(B+C)-G

Doubling

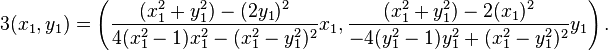

Doubling can be performed with exactly the same formula as addition. Doubling refers to the case in which the inputs (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are known to be equal. Since (x1, y1) is on the Edwards curve, one can substitute the coefficient by (x12 + y12 − 1)/x12y12 as follows:

This reduces the degree of the denominator from 4 to 2 which is reflected in faster doublings. A general addition in Edwards coordinates takes 10M + 1S + 1C + 1D + 7a and doubling costs 3M + 4S + 3C + 6a where M is field multiplications, S is field squarings, D is the cost of multiplying by a selectable curve parameter and a is field addition.

- Example of doubling

As in the previous example for the addition law, let's consider the Edwards curve with d=2:

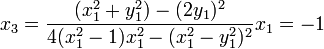

and the point P1=(1,0). The coordinates of the point 2P1 are:

The point obtained from doubling P1 is thus P3=(0,-1).

Mixed Addition

Mixed addition is the case when Z2 is known to be 1. In such a case A=Z1.Z2 can be eliminated and the total cost reduces to 9M+1S+1C+1D+7a

Algorithm

A= Z1.Z2

B= Z12

C=X1.X2

D=Y1.Y2

E=d.C.D

F=B-E

G=B+E

X3= Z1.F((XI+Y1).(X2+Y2)-C-D)

Y3= Z1.G.(D-C)

Z3=C.F.G

Tripling

Tripling can be done by first doubling the point and then adding the result to itself. By applying the curve equation as in doubling, we obtain

There are two sets of formulas for this operation in standard Edwards coordinates. The first one costs 9M + 4S while the second needs 7M + 7S. If the S/M ratio is very small, specifically below 2/3, then the second set is better while for larger ratios the first one is to be preferred.[3] Using the addition and doubling formulas (as mentioned above) the point (X1 : Y1 : Z1) is symbolically computed as 3(X1 : Y1 : Z1) and compared with (X3 : Y3 : Z3)

- Example of tripling

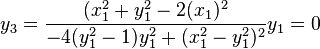

Giving the Edwards curve with d=2, and the point P1=(1,0), the point 3P1 has coordinates:

So, 3P1=(-1,0)=P-1. This result can also be found considering the doubling example: 2P1=(0,1), so 3P1 = 2P1 + P1 = (0,-1) + P1 = -P1.

- Algorithm

A=X12

B=Y12

C=(2Z1)2

D=A+B

E=D2

F=2D.(A-B)

G=E-B.C

H=E-A.C

I=F+H

J=F-G

X3=G.J.X1

Y3=H.I.Y1

Z3=I.J.Z1

This formula costs 9M + 4S

Inverted Edwards coordinates

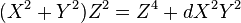

Bernstein and Lange introduced an even faster coordinate system for elliptic curves called the Inverted Edward coordinates[4] in which the coordinates (X : Y : Z) satisfy the curve (X2 + Y2)Z2 = (dZ4 + X2Y2) and corresponds to the affine point (Z/X, Z/Y) on the Edwards curve x2 + y2 = 1 + dx2y2 with XYZ ≠ 0.

Inverted Edwards coordinates, unlike standard Edwards coordinates, do not have complete addition formulas: some points, such as the neutral element, must be handled separately. But the addition formulas still have the advantage of strong unification: they can be used without change to double a point.

For more information about operations with these coordinates see http://hyperelliptic.org/EFD/g1p/auto-edwards-inverted.html

Extended Coordinates for Edward Curves

There is another coordinates system with which an Edwards curve can be represented; these new coordinates are called extended coordinates[5] and are even faster than inverted coordinates. For more information about the time-cost required in the operations with these coordinates see: http://hyperelliptic.org/EFD/g1p/auto-edwards.html

See also

For more information about the running-time required in a specific case, see Table of costs of operations in elliptic curves.

Notes

- ↑ Christophe Arene; Tanja Lange; Michael Naehrig; Christophe Ritzenthaler (2009). "Faster Computation of the Tate Pairing". Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- 1 2 Daniel. J. Bernstein , Tanja Lange, pag. 3, Faster addition and doubling on elliptic curves

- ↑ Bernstein et al., Optimizing Double-Base Elliptic curve single-scalar Multiplication

- ↑ Daniel J.Bernstein . Tanja Lange , pag.2, Inverted Edward coordinates

- ↑ H. Hisil, K. K. Wong, G. Carter, E. Dawson Faster group operations on elliptic curves

References

- Daniel Bernstein, T.Lange (2007), Faster Addition and Doubling on Elliptic curves (PDF)

- Edwards, Harold M. (9 April 2007), "A normal form for elliptic curves", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society (Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society) 44: 393–422, doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-07-01153-6, ISSN 0002-9904, retrieved 2010-01-29

- Faster Group Operations on Elliptic curves, H. Hisil, K. K. Wong, G. Carter, E. Dawson

- D.J.Bernstein, P.Birkner. T. Lange, C.Peters, Optimizing Double-Base Elliptic-Curve Single-Scalar Multiplication (PDF)

- Washington, Lawrence C. (2008), Elliptic Curves: Number Theory and Cryptography, Discrete Mathematics and its Applications (2nd ed.), Chapman & Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1-4200-7146-7

- Daniel J. Bernstein, T. Lange, Inverted Edwards coordinates (PDF)

![\begin{align}

2(x_1,y_1) & = (x_1,y_1)+(x_1,y_1) \\[6pt]

2(x_1,y_1) & = \left( \frac{2x_1y_1}{1+dx_1^2y_1^2}, \frac{y_1^2-x_1^2}{1-dx_1^2y_1^2} \right) \\[6pt]

& = \left( \frac{2x_1y_1}{x_1^2+y_1^2}, \frac{y_1^2-x_1^2}{2-x_1^2-y_1^2} \right)

\end{align}](../I/m/6c8344df75b4cce0eac4c8b0c3df3b45.png)