Edvard Beneš

| Edvard Beneš | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd & 4th President of Czechoslovakia | |

|

In office 2 April 1945 – 7 June 1948 | |

| Preceded by | Emil Hácha |

| Succeeded by | Klement Gottwald |

|

In office 18 December 1935 – 5 October 1938 | |

| Preceded by | Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk |

| Succeeded by | Emil Hácha |

| President of Czechoslovakia in exile | |

|

In office October 1939 – 2 April 1945 | |

| Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia | |

|

In office 26 September 1921 – 7 October 1922 | |

| Preceded by | Jan Černý |

| Succeeded by | Antonín Švehla |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs of Czechoslovakia | |

|

In office 14 November 1918 – 18 December 1935 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Milan Hodža |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

28 May 1884 Kožlany, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (now Czech Republic) |

| Died |

3 September 1948 (aged 64) Sezimovo Ústí, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic) |

| Political party | Czechoslovak National Socialist Party |

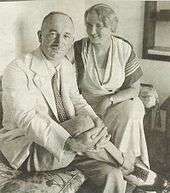

| Spouse(s) | Hana Benešová |

Edvard Beneš (Czech pronunciation: [ˈɛdvard ˈbɛnɛʃ]; 17 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czechoslovak politician who served as the President of Czechoslovakia twice, from 1935–1938 and 1939–1948. He was also Minister of Foreign Affairs (1918–1935), Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia (1921–1922) and the President of Czechoslovakia in exile (1939–1945). A member of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, he was known as a skilled diplomat.[1]

Early life and education

Edvard Beneš was born into a peasant family in the small town of Kožlany, Bohemia, in the Empire of Austria-Hungary, on 17 May 1884.[2] His brother was the Czechoslovak politician Vojta Beneš, grandfather of Emilie Benes Brzezinski. His grandnephew is Václav E. Beneš, a Czech-American mathematician.[3]

Beneš spent much of his youth in the Vinohrady district of Prague, where he attended a grammar school from 1896 to 1904. During this time he played football for Slavia Prague.[4] After studies at the Faculty of Philosophy of the Charles University in Prague, he left for Paris and continued his studies at the Sorbonne and at the Independent School of Political and Social Studies (École Libre des Sciences Politiques). He completed his first degree in Dijon, where he received his doctorate of law in 1908. He then taught for three years at the Prague Academy of Commerce, and after his habilitation in the field of philosophy in 1912, he became a lecturer in sociology at Charles University. He was also involved in Scouting.[5]

First exile

During World War I, Beneš was one of the leading organizers of an independent Czechoslovakia from abroad. He organized a Czech pro-independence anti-Austrian secret resistance movement called "Maffia". In September 1915, he went into exile, and in Paris he made intricate diplomatic efforts to gain recognition from France and the United Kingdom for the Czechoslovak independence movement. From 1916–1918 he was a Secretary of the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris and Minister of the Interior and of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Czechoslovak government.

In May 1918, Beneš, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Milan Rastislav Štefánik were reported to be organizing a Czecho-Slovak army to fight for the Western Allies in France, recruited from among Czechs and Slovaks able to get to the front and also from the large emigrant populations in the United States, said to number more than 1,500,000.[6] The force grew into one of tens of thousands and took part in several battles, including Zborov and Bakhmach.

Early Czechoslovakian politics

From 1918 to 1935, Beneš was the first and longest-serving Foreign Minister of Czechoslovakia, a post he held through 10 successive governments, one of which he headed himself from 1921 to 1922. He served in parliament from 1920–1925 and from 1929–1935. He represented Czechoslovakia in talks on the Treaty of Versailles. He briefly returned to the academic world as a professor in 1921.

Between 1923 and 1927 he was a member of the League of Nations Council (serving as president of its committee from 1927–1928). He was a renowned and influential figure at international conferences, such as those at Genoa in 1922, Locarno in 1925, The Hague in 1930, and Lausanne in 1932.

Beneš was a member of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party (until 1925 called the Czechoslovak Socialist Party) and a strong Czechoslovakist - he did not consider Slovaks and Czechs to be separate ethnicities.

First presidency

When President Tomáš Masaryk retired in 1935, Beneš was the obvious choice as his successor.

He opposed Nazi Germany's claim to the German-speaking Sudetenland in 1938. In October 1938 Italy, France and Great Britain signed the Munich Agreement, which allowed for the immediate annexation and military occupation of the Sudetenland by Germany. Czechoslovakia was not consulted on this agreement. Beneš only agreed after France and the United Kingdom let it be known that, if he did not do so, they would become uninterested in the fate of Czechoslovakia (their military alliance with Czechoslovakia notwithstanding).[7]

Beneš was forced to resign on 5 October 1938 under German pressure.[7] Emil Hácha was chosen as President. In March 1939, Hácha's government was bullied into authorising the German occupation of the remaining Czech territory. (Slovakia had declared its nominal independence by then.)

Second exile

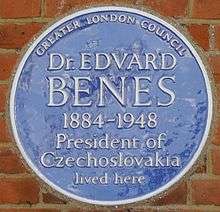

On 22 October 1938 Beneš went into exile in Putney, London. In October 1939, he organised the Czechoslovak National Liberation Committee. In November 1940 in the wake of the London Blitz, Beneš, his wife, their nieces, and his household staff moved to the Abbey at Aston Abbotts near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. The staff of his private office, including his Secretary Edvard Táborský and his chief of staff Jaromír Smutný, moved to the Old Manor House in the neighbouring village of Wingrave, while his military intelligence staff headed by František Moravec was stationed in the nearby village of Addington. In 1940, the UK recognised the National Liberation Committee as the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile, with Jan Šrámek as Prime Minister and Beneš as President. In reclaiming the presidency, Beneš took the line that his 1938 resignation had been under duress, and was therefore void.

In 1941 Beneš and František Moravec planned Operation Anthropoid, with the intention of assassinating Reinhard Heydrich.[8] This was implemented in 1942, and resulted in brutal German reprisals such as the execution of thousands of Czechs and the eradication of the two villages of Lidice and Ležáky.

Although not a Communist, Beneš was also on friendly terms with Stalin. Believing that Czechoslovakia had more to gain from an alliance with the Soviet Union than with Poland, he torpedoed the plans for a Polish-Czechoslovakian confederation and in 1943 he signed an entente with the Soviet Union.[9][10][11]

Second presidency

After the Prague uprising at the end of World War II, Beneš returned home and reassumed his former position as President. He was unanimously confirmed in office the National Assembly on 28 October 1945. Under article 58.5 of the Constitution, "The former president shall stay in his or her function till the new president shall be elected." On 19 June 1946 Beneš was formally elected to his second term as President.[12]

The Beneš decrees (officially called "Decrees of the President of the Republic"), among other things, expropriated the property of citizens of German and Hungarian ethnicity, and facilitated Article 12 of the Potsdam Agreement by laying down a national legal framework for loss of citizenship and expropriation of property of about three million Germans and Hungarians.

Beneš presided over a coalition government, the National Front, from 1946 headed by Communist leader Klement Gottwald as prime minister. On 21 February 1948, 12 non-Communist ministers resigned to protest Gottwald's refusal to stop the packing of the police with Communists, despite a majority of the Cabinet ordering it to end. The non-Communists believed that Beneš would side with them and allow them to stay in office as a caretaker government pending elections.

Beneš initially refused to accept their resignations and insisted that no government could be formed without the non-Communist parties. However, Gottwald threatened a general strike unless Beneš appointed a Communist-dominated government. The Communists also occupied the offices of the non-Communists who had resigned. Amid fears that civil war was imminent and rumours that the Red Army would sweep in to back Gottwald, Beneš gave way on 25 February. He accepted the resignations of the non-Communist ministers and appointed a new government in accordance with Gottwald's specifications. It was nominally still a coalition, but was dominated by Communists and fellow travelers—in effect, giving legal sanction to a Communist coup d'état.

Shortly afterward, elections were held in which voters were presented with a single list from the Communist-dominated National Front. The newly elected National Assembly approved the Ninth-of-May Constitution shortly after being sworn in. Although it was not a completely Communist document, it was close enough to the Soviet Constitution that Beneš refused to sign it. He resigned as President on 7 June 1948; Gottwald succeeded him.

Death

Beneš had been in poor health since suffering two strokes in 1947, and was a broken man after seeing a situation come about that he had made it his life's work to avoid. He died of natural causes at his villa in Sezimovo Ústí, Czechoslovakia on 3 September 1948.[2] He is interred in the garden of his villa, and his bust is part of the gravestone. His wife (who lived until 2 December 1974) is interred beside him.

In fiction

In 1934 H.G.Wells wrote "The Shape of Things to Come", a prediction of the Second World War. In Wells' depiction the war starts in 1940 and drags on until 1950, Czechoslovakia avoids being occupied by Germany, and Beneš remains its President throughout. Wells assigns to Beneš the role of initiating a cease-fire to end the fighting, and the book (supposedly written in the 22nd Century) remarks that "The Beneš Suspension of Hostilities remains in force to this day".

In Prague Counterpoint, the second volume of Bodie and Brock Thoene's Zion Covenant Series, Hitler appoints an assassin to kill Beneš—who fails due to being tackled by an American journalist (and captured by Beneš' bodyguards). But Hitler later uses the execution of this Sudeten Nazi to proclaim him a martyr as a continuing fuse to the Sudeten Crisis.

See also

Further reading

- Hauner, Milan, ed. "'We Must Push Eastwards!' The Challenges and Dilemmas of President Beneš after Munich," Journal of Contemporary History (2009) 44#4 pp. 619–656 in JSTOR

- Lukes, Igor. Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler: The Diplomacy of Edvard Benes in the 1930s (1996) online

- Neville, Peter. Eduard Beneš and Tomáš Masaryk: Czechoslovakia (2011)

- Rees, Neil (2005). The Secret History of the Czech Connection: The Czechoslovak Government in Exile in London and Buckinghamshire During the Second World War. Buckinghamshire: Neil Rees. ISBN 0-9550883-0-5. OCLC 62196328.

- Zbyněk Zeman, Antonín Klimek: The Life of Edvard Beneš 1884-1948: Czechoslovakia in Peace and War, Oxford University Press / Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1997, ISBN 0-19-820583-X ISBN 978-0198205838

Book review by Richard Crampton.[13] - Zinner, Paul E. (1994). "Czechoslovakia: The Diplomacy of Eduard Benes". In Gordon A. Craig and Felix Gilbert. The Diplomats, 1919-1939. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 100–122. ISBN 0-691-03660-8. OCLC 31484352.

- John Wheeler-Bennett Munich : Prologue to Tragedy, New York : Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948.

Primary sources

- Hauner, Milan, ed. Edvard Beneš’ Memoirs: the days of Munich (vol.1), War and Resistance (vol.2), Documents (vol.3). First critical edition of reconstructed War Memoirs 1938-45 of President Beneš of Czechoslovakia (published by Academia Prague 2007. ISBN 978-80-200-1529-7)

References

- ↑ "Edvard Benes - Prague Castle". Hrad.cz. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- 1 2 Dennis Kavanagh (1998). "Benes, Edvard". A Dictionary of Political Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 43. Retrieved 31 August 2013. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Princeton Alumni Weekly - Knihy Google. Books.google.cz. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ "Radio Praha - Stalo se před 100 lety: Robinson a Beneš". Radio.cz. 28 April 2001. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ "Skauting »Historie". Junák - svaz skautů a skautek ČR (in Czech). Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- ↑ 'Czech Army for France' in The Times, Thursday, 23 May 1918, p. 6, col. F

- 1 2 William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

- ↑ "HISTORIE: Špion, kterému nelze věřit - Neviditelný pes". Neviditelnypes.lidovky.cz. 14 March 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ Andrea Orzoff. Battle for the Castle. Oxford University Press US. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-19-974568-5. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ A. T. Lane; Elżbieta Stadtmüller (2005). Europe on the move: the impact of Eastern enlargement on the European Union. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 190. ISBN 978-3-8258-8947-0. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ Roy Francis Leslie; R. F. Leslie (1983). The History of Poland since 1863. Cambridge University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-521-27501-9. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "Prozatimní NS RČS 1945-1946, 2. schůze, část 1/4 (28. 10. 1945)". Psp.cz. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ "Central Europe Review - Book Review: The Life of Edvard Benes, 1884-1948". Ce-review.org. 18 November 1999. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edvard Beneš. |

- President Benes in exile in England during World War II

- Biography at the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Czech)

- "Sons of Death". Time Magazine. 26 September 1938. Retrieved 14 August 2008. (English) - an article published in Time on 26 September 1938 - free archive

- Pictures of Edvard Beneš funeral - lying in state (in the opened coffin)

- Pictures of Edvard Beneš funeral - funeral procession with wreaths and laying of coffin into grave

- Pictures of Edvard Beneš and his wife - archive of Šechtl and Voseček Museum of Photography

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Position established |

Minister of Foreign Affairs of Czechoslovakia 1918–1935 |

Succeeded by Milan Hodža |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk |

President of Czechoslovakia 1935–1938 1945–1948 |

Succeeded by Emil Hácha Klement Gottwald |

| Preceded by Emil Hácha |

President of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile 1940–1945 |

Succeeded by Position abolished |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Marshal Ferdinand Foch |

Cover of Time Magazine 23 March 1925 |

Succeeded by George Harold Sisler |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

|