Ebla

|

Ruins of the outer wall and the "Damascus Gate" | |

Shown within Syria | |

| Alternate name |

Tell Mardikh تل مرديخ |

|---|---|

| Location | Idlib Governorate, Syria |

| Region | Levant |

| Coordinates | 35°47′53″N 36°47′53″E / 35.798°N 36.798°ECoordinates: 35°47′53″N 36°47′53″E / 35.798°N 36.798°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 3500 BC |

| Abandoned | 7th century AD |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Kish civilization, Amorite |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1964–2011 |

| Archaeologists | Paolo Matthiae |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Ebla (Arabic: إبلا, modern: تل مرديخ, Tell Mardikh), was one of the earliest kingdoms in Syria. Its remains constitute a tell located about 55 km (34 mi) southwest of Aleppo near the village of Mardikh. Ebla was an important center throughout the third millennium BC and in the first half of the second millennium BC. Its discovery proved the Levant was a center of ancient, centralized civilization equal to Egypt and Mesopotamia, and ruled out the view that the latter two were the only important centers in the Near East during the early Bronze Age. Karl Moore described the first Eblaite kingdom as the first recorded world power.[1]

Starting as a small settlement in the early Bronze Age (c. 3500 BC), Ebla developed into a trading empire and later into an expansionist power that imposed its hegemony over much of northern and eastern Syria. Its language, Eblaite, is now considered the earliest attested Semitic language after Akkadian. Ebla was destroyed during the 23rd century BC; it was then rebuilt and was mentioned in the records of the Third Dynasty of Ur. The second Ebla was a continuation of the first, ruled by a new royal dynasty. It was destroyed at the end of the third millennium BC, which paved the way for the Amorite tribes to settle in the city, forming the third Ebla. The third kingdom also flourished as a trade center; it became a subject and an ally of Yamhad (modern-day Aleppo) until its final destruction by the Hittite king Mursili I in c. 1600 BC.

Ebla maintained its prosperity through a vast trading network. Artifacts from Sumer, Cyprus, Egypt and as far as Afghanistan were recovered from the city's palaces. The political organization of Ebla had features different from the Sumerian model. Women enjoyed a special status and the queen had major influence in the state and religious affairs. The pantheon of gods was mainly north Semitic and included deities exclusive to Ebla. The city was excavated starting in 1964, and became famous for the Ebla tablets, an archive of about 20,000 cuneiform tablets found there, dated to around 2350 BC.[note 1] Written in both Sumerian and Eblaite and using the cuneiform, the archive has allowed a better understanding of the Sumerian language and provided important information over the political organization and social customs of the mid third millennium BC's Levant.

History

A possible meaning of the word "Ebla" is "white rock", referring to the limestone outcrop on which the city was built.[2][3] Ebla was first settled around 3500 BC;[4][5] its growth was supported by many satellite agricultural settlements. The city benefited from its role as an entrepôt of growing international trade, which probably began with an increased demand for wool in Sumer.[4] Archaeologists designate this early habitation period "Mardikh I"; it ended around 3000 BC.[6] Mardikh I is followed by the first and second kingdoms era between about 3000 and 2000 BC, designated "Mardikh II".[7] I. J. Gelb consider Ebla as part of the Kish civilization, which was a cultural entity of East Semitic-speaking populations that stretched from the center of Mesopotamia to the western Levant.[8]

First kingdom

| First Eblaite Kingdom | |||||

| Ebla | |||||

| |||||

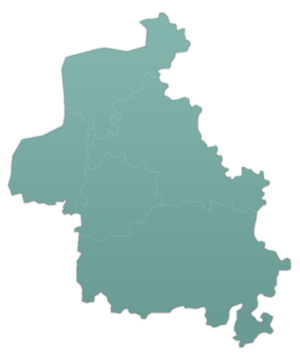

The first kingdom at its greatest extent, including vassals | |||||

| Capital | Ebla | ||||

| Languages | Eblaite language | ||||

| Religion | Levantine Religion.[9] | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||

| • | Established | c. 3000 BC | |||

| • | Disestablished | c. 2300 BC | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

During the first kingdom period between about 3000 and 2300 BC, Ebla was the most prominent kingdom among the Syrian states, especially during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC, which is known as "the age of the archives" after the Ebla tablets.[7]

Early period

The early period between 3000 and 2400 BC is designated "Mardikh IIA".[7][10] General knowledge about the city's history prior to the written archives is obtained through excavations.[11] The first stages of Mardikh IIA is identified with building "CC",[12] and structures that form a part of building "G2",[13] which was apparently a royal palace built c. 2700 BC.[4][14] Toward the end of this period, a hundred years' war with Mari started.[15][16] Mari gained the upper hand through the actions of its king Saʿumu, who conquered many of Ebla's cities.[17] In the mid-25th century BC, king Kun-Damu defeated Mari, but the state's power declined following his reign.[note 2][18]

Archive period

The archive period, which is designated "Mardikh IIB1", lasted from c. 2400 BC until c. 2300 BC.[7] The end of the period is known as the "first destruction",[19] mainly referring to the destruction of the royal palace (called palace "G" and built over the earlier "G2"),[20] and much of the acropolis.[21] During the archive period, Ebla had political and military dominance over the other Syrian city-states of northern and eastern Syria, which are mentioned in the archives.[22] Most of the tablets, which date from that period, are about economic matters but also include royal letters and diplomatic documents.[23]

The written archives do not date from before Igrish-Halam's reign,[24] which saw Ebla paying tribute to Mari,[15] and an extensive invasion of Eblaite cities in the middle Euphrates region led by the Mariote king Iblul-Il.[25][26] Ebla recovered under King Irkab-Damu in about 2340 BC; becoming prosperous and launching a successful counter-offensive against Mari.[27][28] Irkab-Damu concluded a peace and trading treaty with Abarsal;[note 3][29] it is one of the earliest-recorded treaties in history.[30]

At its greatest extent, Ebla controlled an area roughly half the size of modern Syria,[31] from Ursa'um in the north,[32] to the area around Damascus in the south,[33] and from Phoenicia and the coastal mountains in the west,[34][35] to Haddu in the east.[29][36] Half of kingdom was under the direct control of the king and was administered by governors; the rest consisted of vassal kingdoms paying tribute and supplying military assistance to Ebla.[31] One of the most important of these vassals was Armi,[37] which is the city most often mentioned in the Ebla tablets.[38] Ebla had more than sixty vassal kingdoms and city-states,[39] including Hazuwan, Burman, Emar, Halabitu and Salbatu.[28][36][40]

The vizier was the king's chief official.[41] The holder of the office possessed great authority; the most powerful vizier was Ibrium, who campaigned against Abarsal during the term of his predecessor Arrukum.[42] During the reign of Isar-Damu, Ebla continued the war against Mari, which defeated Ebla's ally Nagar, blocking trade routes between Ebla and southern Mesopotamia via upper Mesopotamia.[15] Ebla conducted regular military campaigns against rebellious vassals,[42] including several attacks on Armi,[43][44][45] and a campaign against the southern city of Ibal—close to Qatna.[42][46] In order to settle the war with Mari, Isar-Damu allied with Nagar and Kish.[47] The campaign was headed by the Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish, who led the combined armies to victory in a battle near Terqa.[42] The alliance also attacked Armi and occupied it, leaving Ibbi-Sipish's son Enzi-Malik as governor.[45] Ebla suffered its first destruction a few years after the campaign,[48] probably following Isar-Damu's death.[49]

First destruction of Ebla

The first destruction occurred c. 2300 BC; palace "G" was burned, baking the clay tablets of the royal archives and preserving them.[50] Many theories about the cause and the perpetrator have been posited:[48]

- High (early) dating hypothesis: Giovanni Pettinato supports an early dating for Ebla that would put the destruction at around 2500 BC.[note 4][52] Pettinato, while preferring the date of 2500 BC, later accepted the event could have happened in 2400 BC.[note 5][53] The scholar suggests the city was destroyed in 2400 BC by a Mesopotamian such as Eannatum of Lagash—who boasted of taking tribute from Mari—or Lugalzagesi of Umma, who claimed to have reached the Mediterranean.[note 6][53]

- Akkadian hypothesis: Both kings Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin claimed to have destroyed a town called Ibla,[54] The discoverer of Ebla, Paolo Matthiae, considers Sargon a more likely culprit;[note 7][56] his view is supported by Trevor Bryce,[57] but rejected by Michael Astour.[note 8][60]

- Mari's revenge: According to Alfonso Archi and Maria Biga, the destruction happened approximately three or four years after the battle of Terqa.[48] Archi and Biga say the destruction was caused by Mari[48] in retaliation for its humiliating defeat at Terqa.[61] This view is supported by Mario Liverani.[42] Archi says the Mariote king Isqi-Mari destroyed Ebla before ascending the throne of his city.[62]

- Natural catastrophe: Astour says a natural catastrophe caused the blaze which ended the archive period.[21] He says the destruction was limited to the area of the royal palace and there is no convincing evidence of looting.[21] He dates the fire to c. 2290 BC (Middle Chronology).[63]

Second kingdom

| Second Eblaite Kingdom | |||||

| Ebla | |||||

| |||||

Approximate borders of the second kingdom | |||||

| Capital | Ebla | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||

| • | Established | c. 2300 BC | |||

| • | Disestablished | c. 2000 BC | |||

The second kingdom's period is designated "Mardikh IIB2", and spans the period between 2300 and 2000 BC.[19] The second kingdom lasted until Ebla's second destruction, which occurred anytime between 2050 and 1950 BC, with the 2000 BC dating being a mere formal date.[64][65] The Akkadians under Sargon and his descendant Naram-Sin invaded the northern borders of Ebla aiming for the forests of the Amanus Mountain; the intrusions were separated by roughly 90 years and the areas attacked were not attached to Akkad.[16]

A new local dynasty ruled the second kingdom of Ebla,[57] but there was continuity with its first kingdom heritage.[66] Ebla maintained its earliest features, including its architectural style and the sanctity of the first kingdom's religious sites.[67] A new royal palace was built in the lower town,[68] and the transition from the archive period is marked only by the destruction of palace "G".[21] Little is known about the second kingdom because no written material have been discovered aside from one inscription dating to the end of the period.[68]

The second kingdom was attested to in contemporaneous sources; in an inscription, Gudea of Lagash asked for cedars to be brought from Urshu in the mountains of Ebla, indicating Ebla's territory included Urshu north of Carchemish in modern-day Turkey.[69] Texts that dates to the seventh year of Amar-Sin (c. 2040 BC),[note 9] a ruler of the Ur III empire, mention a messenger of the Ensí ("Megum") of Ebla.[note 10][note 11][76] The second kingdom was considered a vassal by the Ur III government,[77] but the nature of the relation is unknown and it included the payment of tribute.[78] A formal recognition of Ur's overlordship appears to be a condition for the right of trade with that empire.[79]

The second kingdom disintegrated toward the end of the 21st century BC,[32] and ended with the destruction of the city by fire, although evidence for the event has only been found outside of the so called "Temple of the Rock", and in the area around palace "E" on the acropolis.[67] The reason for the destruction is not known;[67] according to Astour, it could have been the result of a Hurrian invasion c. 2030 BC,[80] led by the former Eblaite vassal city of Ikinkalis.[note 12][82] The destruction of Ebla is mentioned in the fragmentary Hurro-Hittite legendary epic "Song of Release" discovered in 1983,[83] which Astour considers as describing the destruction of the second kingdom.[84] In the epic, an Eblaite assembly led by a man called "Zazalla" prevents king Meki from showing mercy to prisoners from Ebla's former vassal Ikinkalis,[81] provoking the wrath of the Hurrian storm god Teshub and causing him to destroy the city.[85]

Third kingdom

| Third Eblaite Kingdom | |||||

| Ebla | |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Ebla | ||||

| Languages | Amorite language.[86] | ||||

| Religion | Levantine Religion | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||

| • | Established | c. 2000 BC | |||

| • | Disestablished | c. 1600 BC | |||

The third kingdom is designated "Mardikh III"; it is divided into periods "A" (c. 2000–1800 BC) and "B" (c. 1800–1600 BC).[19] In period "A", Ebla was quickly rebuilt as a planned city.[87] The foundations covered the remains of Mardikh II; new palaces and temples were built, and new fortifications were built in two circles—one for the low city and one for the acropolis.[87] The city was laid out on regular lines and large public buildings were built.[88][89] Further construction took place in period "B".[88]

The first known king of the third kingdom is Ibbit-Lim,[90] who described himself as the Mekim of Ebla.[note 13][73] A basalt votive statue bearing Ibbit-Lim's inscription was discovered in 1968; this helped to identify the site of Tell-Mardikh with the ancient kingdom Ebla.[73][92] The name of the king is Amorite in the view of Pettinato; it is therefore probable the inhabitants of third kingdom Ebla were predominantly Amorites, as were most of the inhabitants of Syria at that time.[93]

By the beginning of the 18th century BC, Ebla had become a vassal of Yamhad, an Amorite kingdom centered in Aleppo.[94][95] Written records are not available for this period, but the city was still a vassal during Yarim-Lim III of Yamhad's reign.[88] One of the known rulers of Ebla during this period was Immeya, who received gifts from the Egyptian Pharaoh Hotepibre, indicating the continuing wide connections and importance of Ebla.[96] The city was mentioned in tablets from the Yamhadite vassal city of Alalakh in modern-day Turkey; an Eblaite princess married a son of King Ammitaqum of Alalakh, who belonged to a branch of the royal Yamhadite dynasty.[97][98]

Ebla was destroyed by the Hittite King Mursili I in about 1600 BC.[99] Indilimma was probably the last king of Ebla;[100] a seal of his crown prince Maratewari was discovered in the western palace "Q".[100][101] According to Archi, the "Song of Release" epic describes the destruction of the third kingdom and preserves older elements.[81]

Later periods

Ebla never recovered from its third destruction. It was a small village in the phase designated "Mardikh IV" (1600–1200 BC),[99] and was mentioned in the records of Alalakh as a vassal to the Idrimi dynasty.[102] "Mardikh V" (1200–535 BC) was a rural, early Iron Age settlement that grew in size during later periods.[99] Further development occurred during "Mardikh VI", which lasted until c. 60 AD.[99] "Mardikh VII" began in the 3rd century AD and lasted until the 7th century,[103] after which the site was abandoned.[104]

Organization

City layout

Ebla consisted of a lower town and a raised acropolis in the center.[105] During the first kingdom, the city had an area of 56 hectares and was protected by mud-brick fortifications.[106] Ebla was divided into four districts—each with its own gate in the outer wall.[107] The acropolis included the king's palace "G",[108] and one of two temples in city dedicated to Kura (called the "Red Temple").[109] The lower city included the second temple of Kura in the southeast called "Temple of the Rock".[110] During the second kingdom, a royal palace (Archaic Palace "P5") was built in the lower town northwest of the acropolis,[72] in addition to temple "D" built over the destroyed "Red Temple".[111]

During the third kingdom, Ebla was a large city nearly 60 hectares in size,[112] and was protected by a fortified rampart, with double chambered gates.[113] The acropolis was fortified and separated from the lower town.[114] New royal palace "E" was built on the acropolis (during Mardikh IIIB),[89] and a temple of Ishtar was constructed over the former "Red" and "D" temples (in area "D").[109][115] The lower town was also divided into four districts;[107] palace "P5" was used during Mardikh IIIA,[116] and replaced during Mardikh IIIB by the "Intermediate Palace".[113]

Other building included the vizier palace,[note 14][117] the western palace (in area "Q"),[118] the temple of Shamash (temple "N"), the temple of Rasap (temple "B1") and the northern palace (built over the "Intermediate Palace").[113][119] In the north of the lower town, a second temple for Ishtar was built,[120] while the former "Temple of the Rock" was replaced by a temple of Hadad.[note 15][120] Beneath the western palace, natural caves constituted a royal burial ground; it includes many tombs such as the "Tomb of the Lord of the Goats" and "Tomb of the Princess".[89]

Government

The first kingdom government consisted of the king (styled Malikum) and the grand vizier, who headed a council of elders (Abbu) and the administration.[121] The central administration was located in the acropolis. The queen shared the running of affairs of state with the king,[108] the crown prince was involved in internal matters and the second prince was involved in foreign affairs.[108] Most affairs, including military ones, were handled by the vizier and the administration, which consisted of 13 court dignitaries—each of whom controlled between 400 and 800 men forming a bureaucracy with 11,700 people.[121] Each of the four quarters of the lower city was governed by a chief inspector and many deputies.[108] Smaller cities were governed by governors, each of whom was under the authority of the grand vizier.[122] Women received salaries equal to those of men and could accede to important positions and head government agencies.[123]

The second kingdom was a monarchy[78] but little is known about it because of a lack of written records.[68] The third kingdom was a city-state monarchy with reduced importance under the authority of Yamhad.[124]

Kings of Ebla

The Eblaites worshiped dead kings as gods. For the first kingdom monarchs, tablets listing offerings to kings mention ten names,[57] and another list mentions 33 kings. [note 16][49][126] No kings are known from the second kingdom and all dates are estimates according to the Middle chronology.[4][127]

| Ruler | Reigned | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The first kingdom | ||||

| Sakume | c. 3100 BC.[128] | |||

| Su (.) (...) | Name damaged.[49] | |||

| Ladau | ||||

| Abugar | ||||

| Namnelanu | ||||

| Dumudar | ||||

| Ibla | ||||

| Kulbanu | ||||

| Assanu | ||||

| Samiu | ||||

| Zialu | ||||

| Enmanu | c. 2740 BC.[4] | |||

| Namanu | c. 2720 BC.[4] | |||

| Da (.) (.) | c. 2700 BC.[4] | Name damaged.[49] | ||

| Sagisu | c. 2680 BC.[4] | |||

| Dane'um | c. 2660 BC.[4] | |||

| Ibbini-Lim | c. 2640 BC.[4] | |||

| Ishrut-Damu | c. 2620 BC.[4] | |||

| Isidu | c. 2600 BC.[4] | |||

| Isrut-Halam | c. 2580 BC.[4] | |||

| Iksud | c. 2560 BC.[4] | |||

| Talda-Lim | c. 2540 BC.[4] | |||

| Abur-Lim | c. 2520 BC.[4] | |||

| Agur-Lim | c. 2500 BC.[4] | |||

| Ib-Damu | c. 2480 BC.[4] | A seal bearing his name was found in Kültepe.[73] | ||

| Baga-Damu | c. 2460 BC.[4] | |||

| Enar-Damu | c. 2440 BC.[4] | Amongst the most referenced deified kings in the offering lists.[128] | ||

| Eshar-Malik | c. 2420 BC.[4] | |||

| Kun-Damu | c. 2400 BC.[4] | |||

| Adub-Damu | c. 2380 BC.[4] | Short reign.[18] | ||

| Igrish-Halam | c. 2360 BC.[4] | Ruled 12 years.[129] | ||

| Irkab-Damu | c. 2340 BC.[4] | Ruled 11 years.[29] Rise of vizier Ibrium.[130] | ||

| Isar-Damu | c. 2320 BC.[4] | Ruled about 35 years.[29] Rise of vizier Ibbi-Sipish.[130] | ||

| Ir'ak-Damu | A prince, might have ascended the throne for a short period.[49] | |||

|

The third kingdom | ||||

| Ibbit-Lim | c. 2000 BC.[131] | |||

| Immeya | c. 1750 BC.[132] | His grave is identified with the so called "Tomb of the Lord of the Goats".[96] | ||

| Hammu(....) | A successor of Immeya, not necessarily the direct one, the name was damaged but probably Hammurabi.[133] | |||

| Indilimma | c. 1600 BC.[134] | |||

People, language and culture

The first and second kingdoms

Mardikh II's periods shared the same culture.[116] the population of Ebla during Mardikh IIB1 is estimated to have numbered around 40,000 in the capital, and over 200,000 people in the entire kingdom.[135] The Eblaites of Mardikh II were Semites.[136] Giovanni Pettinato said the Eblaite language was a West Semitic language; Gelb and others said it was an East Semitic dialect closer to the Akkadian language.[137] Academic consensus considers Eblaite an East-Semitic language which exhibits both West-Semitic and East-Semitic features.[note 17][139][140]

Ebla held several religious and social festivals, including rituals for the succession of a new king, which normally lasted for several weeks.[141] The Eblaite calendars were based on a solar year divided into twelve months.[142] Two calendars were discovered; the "old calendar" used during the reign of Igrish-Halam, and a "new calendar" introduced by vizier Ibbi-Sipish.[142] Many months were named in honor of deities; in the new calendar, "Itu be-li" was the first month of the year, and meant "the month of the lord".[143] Each year was given a name instead of a number.[144]

The Eblaites imported Kungas from Nagar,[note 18][146] and used them to draw the carriages of royalty and high officials, as well as diplomatic gifts for allied cities.[146] Society was less centered around the palace and the temple than in Mesopotamian kingdoms. The Eblaite palace was designed around the courtyard, which was open toward the city, thus making the administration approachable. This contrasts with Mesopotamian palaces, which resembled citadels with narrow entrances and limited access to the external courtyard.[147] Music played an important part in the society and musicians were both locals,[148] or hired from other cities such as Mari.[149] Ebla also hired acrobats from Nagar, but later reduced their number and kept some to train local Eblaite acrobats.[150]

The third kingdom

The Mardikh III population was predominately Semitic Amorite.[93] The Amorites were mentioned in the first kingdom's tablets as neighbors and as rural subjects.[151] They came to dominate Ebla after the destruction of the second kingdom[152] and formed the bulk of its population. The city witnessed a great increase in construction, and many palaces, temples and fortifications were built.[153] The Amorite Eblaites worshiped many of the same deities as the Eblaites of earlier periods,[154] and maintained the sanctity of the acropolis in the center of the city.[67] The third kingdom's iconography and royal ideology were under the influence of Yamhad's culture; kingship was received from the Yamhadite deities instead of Ishtar of Ebla, which is evident by the Eblaite seals of Indilimma's period.[155]

Economy

During the first kingdom period, the palace controlled the economy,[122] but wealthy families managed their financial affairs without government intervention.[156] The economic system was redistributive; the palace distributed food to its permanent and seasonal workers. It is estimated that around 40,000 persons contributed to this system, but in general, and unlike in Mesopotamia, land stayed in the hands of villages, which paid an annual share to the palace.[157] Agriculture was mainly pastoral; large herds of cattle were managed by the palace.[157] The city's inhabitants owned around 140,000 head of sheep and goats, and 9,000 cattle.[157]

Ebla derived its prosperity from trade;[157] its wealth was equal to that of the most important Sumerian cities,[158] and its main commercial rival was Mari.[159] Ebla's main articles of trade were probably timber from the nearby mountains, and textiles.[160] Handicrafts also appear to have been a major export, evidenced by the quantity of artifacts recovered from the palaces of the city.[161] Ebla possessed a wide commercial network reaching as far as modern-day Afghanistan.[162] It shipped textiles to Cyprus, possibly through the port of Ugarit,[163] but most of its trade seems to have been directed by river-boat towards Mesopotamia—chiefly Kish.[164] The main palace G was found to contain artifacts dating from Ancient Egypt bearing the names of Pharaohs Khafra and Pepi I.[165]

Ebla continued to be a center of trade during the second kingdom, evidenced by the surrounding cities that appeared during its period and were destroyed along with the city.[note 19][64] Trade continued to be Ebla's main economic activity during the third kingdom; archaeological finds show there was an extensive exchange with Egypt and coastal Syrian cities such as Byblos.[112]

Religion

Ebla was a polytheistic state.[166] During the first kingdom, the pantheon had three genres of deities; in the first and most common there were pairs of gods, such as the deity and his female consort, or divine couples such as the deities that cooperate to create the cosmos, as in the Egyptian and Mesopotamian pantheons.[167] The second genre included single deities, while the third genre consisted of divine pairs who were actually a single deity that had two names.[167] Eblaites worshiped few Mesopotamian deities, preferring northern Semitic gods, some of which were unique to Ebla.

- The first genre included the eastern Semitic chief god Dagan,[168] and his consort, Belatu ("his wife"). The patron gods of the city were Kura, who was unique to Ebla,[169] and his consort Barama.[170] Other major deities included Hadad (Hadda)[171] and his consort Habadu,[172] and Rasap and his consort Adamma.[173]

- The second genre included the Syrian goddess Ishara,[note 20] who was the goddess of the royal family.[170] Ishtar was also worshiped but was mentioned only five times in one of the monthly offering lists, while Ishara was far more important, appearing 40 times.[177] Other deities included Damu;[note 21] Nidakul, who was exclusive to Ebla; the Mesopotamian god Utu;[171] Ashtapi;[179] and Shipish the goddess of the sun who had a temple dedicated to her cult.[180]

- The third genre included the artisan god Kamish/Tit, Kothar-wa-Khasis, the planet Venus represented by twin mountain Gods, Shahar as the morning star and Shalim as the evening star. Eblaites also practiced the deification of dead kings.[167] The four city gates were named after the gods Dagan, Hadda, Rasap and Utu, but it is unknown which gate had which name.[181] Overall, the offering list mentioned about 40 deities receiving sacrifices.[171]

During the third kingdom, Amorites worshiped common northern Semitic gods; the unique Eblaite deities disappeared.[182] Hadad was the most important god, while Ishtar took Ishara's place and became the city's most important deity apart from Hadad.[154]

Biblical connection theories

At the beginning of the process of deciphering the tablets, Pettinato made claims about a possible connections between Ebla and the Bible,[183] citing an alleged references in the tablets to the existence of Yahweh, the Patriarchs, Sodom and Gomorrah and other Biblical references.[183] However, much of the initial media excitement about a supposed Eblaite connections with the Bible, based on preliminary guesses and speculations by Pettinato and others, is now widely discredited as "exceptional and unsubstantiated claims" and "great amounts of disinformation that leaked to the public".[183][184] In Ebla studies, the focus has shifted away from comparisons with the Bible; Ebla is now studied as a civilization in its own right.[183] The change came after a bitter personal and academic conflict between the scholars involved, as well as what some described as political interference by the Syrian authorities.[185]

Discovery and library

In 1964, Italian archaeologists from the University of Rome La Sapienza under the direction of Paolo Matthiae began excavating at Tell Mardikh. In 1968, they recovered a statue dedicated to the goddess Ishtar bearing the name of Ibbit-Lim, mentioning him as king of Ebla.[186] That identified the city, long known from Lagashite and Akkadian inscriptions.[187][188] In the next decade, the team discovered a palace (palace G) dating from c. 2500 – 2000 BC. Finds in the palaces include a small sculpture made out of precious materials, black stones and gold.[158] Other artifacts included wood furniture inlaid with mother-of-pearl and composite statues created from colored stones.[161] A silver bowl bearing king Immeya's name was recovered from the "Tomb of the Lord of the Goats", together with Egyptian jewels and an Egyptian ceremonial mace presented by pharaoh Hotepibre.[96] Ebla's first kingdom is an example of early Syrian centralized states,[189] and is considered one of the earliest empires by scholars[190][191] including Samuel Finer[192] and Karl Moore, who consider it the first-recorded world power.[1] Ebla's discovery changed the former view of Syria's history as a bridge between Mesopotamia and Egypt; it proved the region was a center of civilization in its own right.[193][194]

About 20,000 cuneiform tablets[195] consisting of 2,500 well-preserved, complete tablets and thousands of fragments, were discovered in the site.[196] About 80% of the tablets are written using the usual Sumerian combination of logograms and phonetic signs,[197] while the others exhibited an innovative, purely phonetic representation using Sumerian cuneiform of a previously unknown Semitic language, which was called "Eblaite".[198] Bilingual Sumerian/Eblaite vocabulary lists were found among the tablets, allowing them to be translated.[181]

Ebla's close link to southern Mesopotamia, where the script had developed, further highlights the contemporaneous links between the Sumerians and Semitic cultures. The tablets provide many important insights into the cultural, economic and political life in northern Mesopotamia around the middle of the 3rd millennium BC.[199] They also provide insight into the everyday lives of the inhabitants and containing information about state revenues, Sumerian-Eblaite dictionaries,[181] school texts, an archive of provisions and tribute, law cases,[200] diplomatic and trade contacts, and a scriptorium where apprentices copied texts.[201] The tablets also contain writings on Ebla's hymns, legends, scientific observations and magic.[198]

Library

The tablets constitute one of the oldest archives and libraries ever found; there is tangible evidence of their arrangement and even classification.[202] The larger tablets had originally been stored on shelves, but had fallen onto the floor when the palace was destroyed.[203] The locations of the fallen tablets allowed the excavators to reconstruct their original positions on the shelves; they found the tablets had originally been shelved according to subject.[204]

These features were absent from earlier Sumerian excavations. Sophisticated techniques of arrangement of texts, coupled with their composition, evidence the great antiquity of archival and library practices, which may be far older than was assumed to be the case before the discovery of the Ebla library.[202] A sizable portion of the tablets contain literary and lexicographic texts; evidence seems to suggest the collection also served—at least partially—as a true library rather than a collection of archives intended solely for use by the kings, their ministers, and their bureaucracy.[202] The tablets show evidence of the early transcription of texts into foreign languages and scripts, classification and cataloging for easier retrieval, and arrangement by size, form and content.[202] The Ebla tablets have thus provided scholars with new insights into the origin of library practices that were in use 4,500 years ago.

Current situation

As a result of the Syrian Civil War, excavations of Ebla stopped in March 2011,[205] and large-scale looting occurred after the site came under the control of an opposition armed group.[206] Many tunnels were dug and a crypt full of human remains was discovered; the remains were scattered and discarded by the robbers, who hoped to find jewelry and other precious artifacts.[206] Digging all around the mound was conducted by nearby villagers with the aim of finding artifacts; some villagers removed carloads of soil suitable for making ceramic liners for bread-baking ovens from the tunnels.[206]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All dates in the article are estimated by the Middle Chronology, unless stated otherwise.

- ↑ The political weakness started during the short reign of Adub-Damu.[18]

- ↑ Probably located along the Euphrates river east of Ebla.[29]

- ↑ At first Pettinato supported the Naram-Sin theory before proposing the High dating.[51]

- ↑ Michael Astour argues that using the chronology accepted by Pettinato, one obtains the date of 2500 BC for the reign of Ur-Nanshe of Lagash, who ruled approximately 150 years prior to Lagash's destruction at the hands of king Lugalzagesi. Since Ur-Nanshe ruled in 2500 BC, and his reign is separated by at least 150 years from Hidar of Mari's reign which saw Ebla's destruction, then the date for that event is pulled beyond 2500 BC and even 2400 BC.[51]

- ↑ Astour argue that according to the middle chronology used for the 2400 BC date, Eannatum's reign ended in 2425 BC and Ebla was not destroyed until 2400 BC; according to the same chronology Lugalzagesi's reign would have started fifty years after 2400 BC.[53]

- ↑ At first Matthiae supported the Naram-Sin theory then switched to Sargon.[55]

- ↑ Astour believes that Sargon and his grandson were referring to a city with a similar name in Iraq named "Ib-la".[58] Astour says the archives of Ebla at the time of their destruction correspond to the political situation predating the establishment of the Akkadian empire, not just the reign of Naram-Sin.[55] It is also unlikely Sargon was responsible because at the time of their destruction, the Ebla tablets describe Kish as independent. Lugalzagesi sacked Kish and was killed by Sargon before Sargon destroyed Ibla or Ebla.[59]

- ↑ Amar-Sin's reign lasted from 2045 to 2037 BC (middle chronology).[70]

- ↑ "Megum" is thought to have been a title of the ruler of Ebla rather than a personal name.[71] King Ibbit-Lim of the latter third kingdom of Ebla also used this title.[72] An Eblaite seal that reads the sentence Ib-Damu Mekim Ebla, was used in the 19th century BC by an Assyrian merchant named Assur-Nada from Kültepe.[73] Ib Damu was the name of an Eblaite king from the early period of the first kingdom.[73]

- ↑ In a tablet, the name of Ili-Dagan "the man of Ebla" is mentioned, and he was thought to be a ruler.[74] However, other texts mentions him as the envoy of Ebla's ruler.[75]

- ↑ Unidentified location to the north of Ebla in the proximity of Alalakh.[81]

- ↑ This led Astour, David I. Owen and Ron Veenker to identify Ibbit-Lim with the pre-Amorite Megum of the Third Ur era.[91] However, this identification is now refuted.[72]

- ↑ Called the southern palace (in area "FF"), it was located at the foot of the southern side of the acropolis.[117]

- ↑ Area HH.[117]

- ↑ Tablet TM.74.G.120 discovered by Alfonso Archi.[126]

- ↑ Grammatically, Eblaite is closer to Akkadian, but lexically and in some grammatical forms, Eblaite is closer to West-Semitic languages.[138]

- ↑ The Kunga is a hybrid of a donkey and a female onager, which Nagar was famous for breeding.[145]

- ↑ Archaeologist Alessandro de Maigret deduced that Ebla retained its trading position.[64]

- ↑ At the beginning of Ebla's studies, it was believed that the existence of Ishara and another god Ashtapi in Ebla's pantheon, is a proof for a Hurrian existence in the Eblaite first kingdom.[174] However it is now known that those deities were pre-Hurrian and perhaps pre-Semitic deities, later incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon.[154][175][176]

- ↑ Probably an old Semitic deity and not identical to the Sumerian Damu.[178]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Karl Moore,David Charles Lewis (2009). The Origins of Globalization. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-135-97008-6.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 248. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. pp. 241, 242. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- ↑ Ian Shaw,Robert Jameson (2008). A Dictionary of Archaeology. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-470-75196-1.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2009). Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8108-6324-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- ↑ Donald P. Hansen, Erica Ehrenberg (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-57506-055-2.

- ↑ Sarah Iles Johnston (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- ↑ Sharon R. Steadman,Gregory McMahon (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). p. 268. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 250. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 247. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 246. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Hartmut Kühne,Rainer Maria Czichon,Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). 4 ICAANE. p. 66. ISBN 978-3-447-05757-8.

- 1 2 3 "Monuments of War, War of Monuments: Some Considerations on Commemorating War in the Third Millennium BC. Orientalia Vol.76/4". Davide Nadali. 2007. p. 349,350. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- 1 2 3 Hartmut Kühne, Rainer Maria Czichon, Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). 4 ICAANE. p. 68. ISBN 978-3-447-05757-8.

- 1 2 3 Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon, Gary Rendsburg, Nathan H. Winter (1992). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 3. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-931464-77-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Giovanni Pettinato (1981). The archives of Ebla: an empire inscribed in clay. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-385-13152-0.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- ↑ Regine Pruzsinszky, Dahlia Shehata (2010). Musiker und Tradierung: Studien Zur Rolle Von Musikern Bei Der Verschriftlichung und Tradierung Von Literarischen Werken. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-643-50131-8.

- ↑ Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-14-193825-7.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 40. ISBN 978-90-04-13158-3.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-979875-9.

- 1 2 Lisa Cooper (2006). Early Urbanism on the Syrian Euphrates. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-134-26107-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Alfonso Archi and Maria Giovanna Biga, In Search of Armi, Journal of Cuneiform Studies Vol. 63, pp. 5-34". The American Schools of Oriental Research. 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Stephen C. Neff (2014). Justice Among Nations. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-72654-3.

- 1 2 William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Jonathan N. Tubb (1998). Canaanites. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8061-3108-5.

- ↑ Maria Eugenia Aubet (2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-521-79543-2.

- ↑ Gordon Douglas Young (1981). Ugarit in Retrospect: Fifty Years of Ugarit and Ugaritic. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-931464-07-2.

- 1 2 Diane Bolger, Louise C. Maguire (2010). The Development of Pre-State Communities in the Ancient Near East: Studies in Honour of Edgar Peltenburg. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-84217-837-9.

- ↑ Giovanni Pettinato (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8018-4150-7.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 486. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 484. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 485. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- 1 2 Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 486. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Nicole Brisch, Jesper Eidem (2014). Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-11-026641-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-316-19503-1.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- 1 2 3 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Harry A. Hoffner, Gary M. Beckman, Richard Henry Beal, John Gregory McMahon (2003). Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner, Jr: On the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-57506-079-8.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon ,Gary Rendsburg, Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- 1 2 3 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- ↑ Wayne Horowitz (1998). Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-931464-99-7.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-979875-9.

- ↑ "War of the lords. The battle of chronology. Page 7". Joachim Bretschneider, Anne-Sophie Van Vyve, Greta Jans Leuven. 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- 1 2 3 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 245. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 252. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- 1 2 3 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2015). Ur: The City of the Moon God. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4725-3169-8.

- ↑ Università degli studi di Roma "La Sapienza." Dipartimento di scienze storiche, archeologiche ed antropologiche dell'antichità (2000). Proceedings of the First International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Rome, May 18th–23rd 1998, Volume 2. p. 1405. ISBN 978-88-88233-00-0.

- 1 2 3 Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- ↑ Goetze, Albrecht (1953). "Four Ur Dynasty Tablets Mentioning Foreigners". Journal of Cuneiform Studies 7 (3): 103. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359547.

- ↑ Edward Lipiński, Karel van Lerberghe, Antoon Schoors (1995). Immigration and Emigration Within the Ancient Near East: Festschrift E. Lipiński. p. 185. ISBN 978-90-6831-727-5.

- ↑ Horst Klengel (1992). Syria, 3000 to 300 B.C.: a handbook of political history. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-05-001820-1.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- 1 2 3 Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ David Konstan,Kurt A. Raaflaub (2009). Epic and History. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4443-1564-6.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ David Konstan,Kurt A. Raaflaub (2009). Epic and History. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4443-1564-6.

- ↑ Harvey Weiss (1985). Ebla to Damascus: Art and Archaeology of Ancient Syria : an Exhibition from the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums of the Syrian Arab Republic. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-86528-029-8.

- 1 2 Jack Cheng,Marian H. Feldman (2007). Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context. p. 75. ISBN 90-04-15702-6.

- 1 2 3 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- 1 2 3 Watson E. Mills,Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- ↑ Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic (2013). Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-58839-475-0.

- ↑ Horst Klengel (1992). Syria, 3000 to 300 B.C.: a handbook of political history. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-05-001820-1.

- ↑ Joan Aruz (2013). Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-58839-475-0.

- 1 2 Giovanni Pettinato (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8018-4150-7.

- ↑ Mogens Herman Hansen (2007). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation, Volume 21. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-57506-135-1.

- ↑ Marlies Heinz,Marian H. Feldman (2000). Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East. p. 55. ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4.

- 1 2 3 Joan Aruz,Kim Benzel,Jean M. Evans (2008). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-58839-295-4.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC). p. 807. ISBN 978-0-8020-5873-7.

- ↑ Beatrice Teissier (1984). Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals from the Marcopolic Collection. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-520-04927-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-134-15908-6.

- 1 2 Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic (2013). Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-58839-475-0.

- ↑ Seymour Gitin, J. Edward Wright, J. P. Dessel (2006). Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-57506-117-7.

- ↑ Michael.C.Astour (1969). Orientalia: Vol. 38. p. 388.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck,Eberhard Otto,Wolfhart Westendorf (1986). Lexikon der Ägyptologie: Stele-Zypresse. -1986. -VIII p.-1456 col.- [1] dépl. p. 347. ISBN 978-3-447-02663-5.

- ↑ Watson E. Mills,Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- ↑ Diane Bolger, Louise C. Maguire (2010). The Development of Pre-State Communities in the Ancient Near East: Studies in Honour of Edgar Peltenburg. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-84217-837-9.

- ↑ Lorenzo Nigro (2007). Byblos and Jericho in the Early Bronze I: Social Dynamics and Cultural Interactions : Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Rome on March 6th 2007 by Rome "La Sapienza" University. p. 110. ISSN 1826-9206.

- 1 2 Lorenzo Nigro (2007). Byblos and Jericho in the Early Bronze I: Social Dynamics and Cultural Interactions : Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Rome on March 6th 2007 by Rome "La Sapienza" University. p. 112. ISSN 1826-9206.

- 1 2 3 4 Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1995). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E–J. p. 537. ISBN 978-0-8028-3782-0.

- 1 2 Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 543. ISBN 978-1-136-21912-2.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Licia Romano (2010). 6 ICAANE. p. 251. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- 1 2 Joan Aruz,Kim Benzel,Jean M. Evans (2008). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-58839-295-4.

- 1 2 3 Margreet L. Steiner,Ann E. Killebrew (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000–332 BCE. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-19-166255-3.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- ↑ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans,Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- 1 2 3 Margreet L. Steiner,Ann E. Killebrew (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000–332 BCE. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-166255-3.

- ↑ Seymour Gitin,J. Edward Wright,J. P. Dessel (2006). Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-57506-117-7.

- ↑ Hartmut Kühne, Rainer Maria Czichon, Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). 4 ICAANE. p. 177. ISBN 978-3-447-05703-5.

- 1 2 Lorenzo Nigro (2007). Byblos and Jericho in the Early Bronze I: Social Dynamics and Cultural Interactions : Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Rome on March 6th 2007 by Rome "La Sapienza" University. p. 130. ISSN 1826-9206.

- 1 2 Samuel Edward Finer (1997). The History of Government from the Earliest Times: Ancient monarchies and empires, Volume 1. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-820664-4.

- 1 2 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- ↑ Giovanni Pettinato (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8018-4150-7.

- ↑ William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- ↑ "Seated Ruler, 2000–1700 BC". Cleavland ART Museum. 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700–2350 BC). p. 210. ISBN 978-1-4426-9047-9.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon, Gary Rendsburg, Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700–2350 BC). p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4426-9047-9.

- 1 2 Eric M. Meyers (1997). The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, Volume 2. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-511216-0.

- ↑ Luigi Cagni (1981). La lingua di Ebla: Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Napoli, 21-23 april 1980). p. 78.

- ↑ Joan Aruz (2013). Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-58839-475-0.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae (2010). Ebla: la città del trono : archeologia e storia (in Italian). p. 218. ISBN 978-88-06-20258-3.

- ↑ American Schools of Oriental Research (1984). The Biblical Archaeologist, Volume 47. p. 3.

- ↑ C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky (1991). Archaeological Thought in America. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-521-40643-7.

- ↑ Eric M. Meyers (1997). The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, Volume 2. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-19-511216-0.

- ↑ Robert Hetzron (2013). The Semitic Languages. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-136-11580-6.

- ↑ Watson E. Mills,Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. p. 226.

- ↑ Alan S. Kaye (1991). Semitic studies, Volume 1. p. 550.

- ↑ Robert Hetzron (2013). The Semitic Languages. p. 101.

- ↑ Barbette Stanley Spaeth (2013). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0.

- 1 2 Giovanni Pettinato (1981). The archives of Ebla: an empire inscribed in clay. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-385-13152-0.

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1995). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 4. p. 756. ISBN 978-0-8028-3784-4.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-979875-9.

- ↑ Elena Efimovna Kuzʹmina (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. p. 134. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- 1 2 Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 436. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- ↑ Regine Pruzsinszky, Dahlia Shehata (2010). Musiker und Tradierung: Studien Zur Rolle Von Musikern Bei Der Verschriftlichung und Tradierung Von Literarischen Werken. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-643-50131-8.

- ↑ Regine Pruzsinszky, Dahlia Shehata (2010). Musiker und Tradierung: Studien Zur Rolle Von Musikern Bei Der Verschriftlichung und Tradierung Von Literarischen Werken. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-643-50131-8.

- ↑ David Oates, Joan Oates, Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-9519420-9-3.

- ↑ Hartmut Kühne,Rainer Maria Czichon,Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). 4 ICAANE. p. 205. ISBN 978-3-447-05757-8.

- ↑ Brian M. Fagan,Charlotte Beck (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-19-507618-9.

- ↑ Amélie Kuhrt (1995). The Ancient Near East, C. 3000–330 BC. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

- 1 2 3 Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- ↑ Pelio Fronzaroli (2003). Semitic and Assyriological Studies: Presented to Pelio Fronzaroli by Pupils and Colleagues. p. 101. ISBN 978-3-447-04749-4.

- ↑ Giovanni Pettinato (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8018-4150-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- 1 2 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-964667-8.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- 1 2 Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000–300 BC). p. 271. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- ↑ International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament. Congress (1978). Congress Volume. p. 83. ISBN 978-90-04-05835-4.

- ↑ Giovanni Pettinato (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8018-4150-7.

- ↑ Joan Aruz, Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ↑ Craig Davis (2007). Dating the Old Testament. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-9795062-0-8.

- 1 2 3 Cyrus Herzl Gordon,Gary Rendsburg,Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- ↑ Yoël L. Arbeitman (2000). The Asia Minor Connexion: Studies on the Pre-Greek Languages in Memory of Charles Carter. p. 223. ISBN 978-90-429-0798-0.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700–2350 BC). p. 206. ISBN 978-1-4426-9047-9.

- 1 2 Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- 1 2 3 Sarah Iles Johnston (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- ↑ Alfonso Archi (1994). Orientalia: Vol. 63. p. 250.

- ↑ Maciej M. Münnich (2013). The God Resheph in the Ancient Near East. p. 261. ISBN 978-3-16-152491-2.

- ↑ Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Nicole Brisch, Jesper Eidem (2014). Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State. p. 100. ISBN 978-3-11-026641-2.

- ↑ Karel van Lerberghe, Gabriela Voet (1999). Languages and Cultures in Contact: At the Crossroads of Civilizations in the Syro-Mesopotamian Realm ; Proceedings of the 42th [sic] RAI. p. 155. ISBN 978-90-429-0719-5.

- ↑ Daniel E. Fleming (2000). Time at Emar: The Cultic Calendar and the Rituals from the Diviner's Archive. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-57506-044-6.

- ↑ Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon, Gary Rendsburg (1990). Eblaitica: essays on the Ebla archives and Eblaite language, Volume 2. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-931464-49-2.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon, Gary Rendsburg, Nathan H. Winter (1992). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 3. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-931464-77-5.

- ↑ Joan Aruz (2013). Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-58839-475-0.

- 1 2 3 Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 8. ISBN 90-04-13158-2.

- ↑ Hans Gustav Güterbock,K. Aslihan Yener,Harry A. Hoffner,Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Mark W. Chavalas (2003). Mesopotamia and the Bible. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-567-08231-2.

- ↑ Ivan Mannheim (2001). Syria & Lebanon Handbook. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-900949-90-3.

- ↑ William E. Harris (1989). From Man to God: An LDS Scientist Views Creation, Progression and Exaltation. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-88290-345-3.

- ↑ Lorna Oakes (2009). Mesopotamia. p. 751. ISBN 978-0-8028-3784-4.

- ↑ Barbara Ann Kipfer (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-306-46158-3.

- ↑ Barbara Ann Kipfer (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. p. 683. ISBN 978-0-306-46158-3.

- ↑ Anne Porter (2012). Mobile Pastoralism and the Formation of Near Eastern Civilizations: Weaving Together Society. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-521-76443-8.

- ↑ Gordon Douglas Young (1981). Ugarit in Retrospect: Fifty Years of Ugarit and Ugaritic. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-931464-07-2.

- ↑ Susan Pollock, Reinhard Bernbeck (2009). Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4051-3723-2.

- ↑ Samuel Edward Finer (1997). The History of Government from the Earliest Times: Ancient monarchies and empires, Volume 1. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-820664-4.

- ↑ Jimmy Jack McBee Roberts (2002). The Bible and the Ancient Near East: Collected Essays. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-57506-066-8.

- ↑ Margreet L. Steiner,Ann E. Killebrew (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: C. 8000–332 BCE. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-19-921297-2.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon (1987). Forgotten scripts: their ongoing discovery and decipherment. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-88029-170-5.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae (2007). The Royal Archives of Ebla. ISBN 978-88-7624-665-4.

- ↑ Joseph Naveh (1982). Early history of the alphabet: an introduction to West Semitic epigraphy and palaeography. p. 28. ISBN 978-965-223-436-0.

- 1 2 Stuart A. P. Murray (2013). The Library: An Illustrated History. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-62873-322-8.

- ↑ Norman Yoffee,Bradley L. Crowell (2006). Excavating Asian History: Interdisciplinary Studies in Archaeology and History. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8165-2418-1.

- ↑ Mary Tilma (2008). Ancient Book Relevant Faith. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-60647-950-6.

- ↑ Roy MacLeod (2005). The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-85771-438-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Wellisch, Hans H. (1981). Ebla: The World's Oldest Library. The Journal of Library History (1974–1987), Vol. 16, No. 3 (Summer, 1981), pp. 488–500.

- ↑ Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- ↑ Patricia C. Franks (2013). Records and Information Management. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-55570-910-5.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae (2013). Studies on the Archaeology of Ebla 1980–2010. p. ix. ISBN 978-3-447-06937-3.

- 1 2 3 "Grave Robbers and War Steal Syria's History". The New York Times. 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Aruz, Joan (2013). Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-475-0.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-15908-6.

- Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- Finer, Samuel (1997). The History of Government from the Earliest Times: Ancient monarchies and empires, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820664-4.

- Frayne, Douglas (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700–2350 BC). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-9047-9.

- Fronzaroli, Pelio (2003). Semitic and Assyriological Studies: Presented to Pelio Fronzaroli by Pupils and Colleagues. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04749-4.

- Gordon, Cyrus; Rendsburg, Gary; Winter, Nathan (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- Güterbock, Hans; Yener, K. Aslihan; Hoffner, Harry; Dhesi, Simrit (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History: Papers in Memory of Hans G. Güterbock. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-053-8.

- Hamblin, William (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- Klengel, Horst (1992). Syria, 3000 to 300 B.C.: a handbook of political history. Akademie Verlag. ISBN 978-3-05-001820-1.

- Kühne, Hartmut; Czichon, Rainer; Kreppner, Florian (2008). 4 ICAANE. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05757-8.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- Matthiae, Paolo; Marchetti, Nicoló (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. Left Coast Press. ISBN 978-1-61132-228-6.

- Matthiae, Paolo; Romano, Licia (2010). 6 ICAANE. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-06175-9.

- Pettinato, Giovanni (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4150-7.

- Podany, Amanda (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979875-9.

- Spaeth, Barbette (2013). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0.

- Steiner, Margreet; Killebrew, Ann (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000-332 BCE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-166255-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ebla. |

- Ebla (Tell Mardikh) Suggestion to have Ebla (Tell Mardikh) recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site

- Ebla - Tell Mardikh with photos and plans of the digs (Italian)

- Two Weights from Temple N at Tell Mardikh-Ebla, by E. Ascalone and L. Peyronel (pdf)

- The Urban Landscape of Old Syrian Ebla. F. Pinnock (pdf)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|