East Timor–Indonesia relations

|

|

Timor-Leste |

Indonesia |

|---|---|

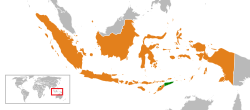

East Timor (officially named the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste) and Indonesia share the island of Timor. Indonesia invaded the former Portuguese colony in 1975 and annexed East Timor in 1976, maintaining East Timor as its 27th province until a United Nations-sponsored referendum in 1999, in which the people of East Timor chose independence. Following a United Nations interim administration, East Timor gained independence in 2002. After 2002, their relations are good. Indonesia has an embassy in Dili. East Timor has an embassy in Jakarta and a consulate in Kupang.

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 1,201,542[1] | 255,461,700[2] |

| Area | 15,410 km2 (5,743 sq mi ) | 1,904,569 km2 (735,358 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 76.2/km2 (197.4/sq mi) | 124.66/km2 (322.87/sq mi) |

| Time zones | 1 | 3 |

| Capital | Dili | Jakarta |

| Largest City | Dili – 222,323 (234,331 Metro) | Jakarta – 11,374,022 (30,326,103 Metro) |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Official language | Tetum, Portuguese | Indonesian |

| Main religions | 96.9% Catholicism, 2.2% Protestantism, 0.3% Islam, 0.5% Other | 87.2% Islam, 6.9% Protestantism, 2.9% Catholicism, 1.6% Hinduism, 0.72% Buddhism, 0.05% Confucianism, 0.5% Other |

| Ethnic groups | Tetum, Mambai, Tukudede, Galoli, Baikeno, Bunak, Fataluku | 40.22% Javanese, 15.5% Sundanese, 3.58% Batak, 3.03% Madurese, 2.88% Betawi, 2.73% Minangkabau, 2.69% Bugis, 2.27% Malay, 27.1% Other |

| GDP (per capita) | $1,847 | $11,135 |

| GDP (nominal) | $1.293 billion | $895.577 billion |

Historical background

Portugal took control of the territory that would become known as Portuguese Timor in the middle of the 18th century, and maintained the eastern half of the island (West Timor was a Dutch possession until World War II) as a colony until Portugal's left-leaning[a] Carnation Revolution in 1974. Portugal declared its intent to give its former colony independence and local parties formed, intending to contest East Timor's first free elections scheduled for 1976. Indonesia, then firmly-rooted in the anti-Soviet camp in Southeast Asia, was alarmed by the left-leaning parties that looked set to win that election. Indonesian invaded the territory in 1975 and annexed East Timor the following year. The subsequent 24-year occupation of East Timor caused great damage to Indonesia's diplomatic relations and to its International reputation.[3]

Falintil, the armed wing of the leftist[b] East Timorese political party Fretilin became the major source of resistance to Indonesia's annexation, but military resistance was eventually all but eliminated. Poet and semi-professional football goalkeeper José Alexandre Gusmão led 20 years of low-level insurrection and diplomatic pressure against the occupation. Gusmão, nicknamed Xanana by his followers, became East Timor's first president following its independence.[4]

East Timorese independence

Following Suharto's forced resignation in 1998, his Vice President and successor BJ Habibie offered a surprise referendum on East Timorese independence.[5] After 78% of East Timorese chose independence in the referendum, Habibie was attacked across the Indonesian political spectrum for betraying national interests and lost what little chance he had of retaining the presidency in Indonesia's October 1999 election.[6] He was replaced by Abdurrahman Wahid, a staunch opponent of East Timorese independence.

Parts of the Indonesian military were strongly opposed to the East Timorese independence and had spent much of 1998 and 1999 arming pro-Indonesia partisans and arranging attacks on independence groups. Within hours of the referendum results being announced by UN Special Envoy to East Timor Jamsheed Marker, the Indonesian military enacted a scorched earth plan in the territory, destroying over half of the territory's fixed infrastructure, killing about 1,500 East Timorese and displacing a further 300,000 people over the next few weeks, until an Australian-led UN peace-keeping force arrived in the country on September 20, 1999.[7]

The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) provided an interim civil administration and a peacekeeping mission in the territory of East Timor, from its establishment in October 1999[8] until the territory's independence on May 20, 2002.

Post 2002

Despite the traumatic past, relations with Indonesia are very good. Indonesia is by far the largest trading partner of East Timor (Approximately 50% of imports, 2005) and is steadily increasing its share.

Problems to be solved include, East Timor-Indonesia Boundary Committee meetings to survey and delimit land boundary; and Indonesia is seeking resolution of East Timorese refugees in Indonesia.

See also

References

- ↑ The World Factbook Estimate 2014 - https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2119.html

- ↑ CBS Estimate May 2015 - http://www.bps.go.id/linkTabelStatis/view/id/1274

- ↑ A Nation in Waiting Chapter 8, East Timor: The little pebble that could, Adam Schwarz, Westview Press, 2nd edition (1999)

- ↑ The President Behind the Nation The Christian Science Monitor, Dan Murphy, May 20, 2002

- ↑ Hafidz, Tatik S.. Fading away?: The political role of the army in Indonesia’s transition to democracy, 1998–2001. Singapore Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, p. 43

- ↑ Criticisms mount over Habibie's East Timor decision The Jakarta Post, September 7, 1999

- ↑ Scorched Earth, Far Eastern Economic Review, John McBeth and Dan Murphy, September 16, 1999, pp. 10–14

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1272. S/RES/1272(1999) (1999) Retrieved 2008-04-12.

Footnotes

- a. ^ "Shortly after midnight on April 25, 1974 young left-wing officers of the Movimento das Forcas Armadas (MFA) overthrew Portugals 48-year-old nationalist dictatorship... (it) came to be known as "the Carnation Revolution."" The Spirit of Democracy, p. 39, Larry Diamond, Macmillan 2008.

- b. ^ "Fretilin was established by a seminary-trained mestizo elite with links to left-wing groups in both Portugal and its African colonies." Dictionary of the modern politics of South-East Asia, p. 115, Michael Leifer, Taylor & Francis, 2001.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||