Outhouse

An outhouse (or privy) is a small structure, separate from a main building, which covers a pit latrine or a dry toilet. Outside North America, the term "outhouse" refers not to a toilet but to outbuildings in a general sense. Colloquially, the term is also used in some countries to denote the toilet itself, not just the small housing structure.

Terminology

The term "outhouse" is used in North American English for the structure over a pit latrine.[1] The structures are referred to by many other terms throughout the English-speaking world, including "dunny" or "long drop" in Australia and New Zealand,[2] and "bog" in the United Kingdom. The terms "kybo" and "biffy" are unique to the Scouting movements.[3] In British English the word "outhouse" is used for any kind of separate or leanto structure and does not specifically refer to any kind of latrine or toilet. In the Welsh Language the expression "ty bach" = little house refers to any toilet, including a normal bathroom internal to a house.

Design and construction

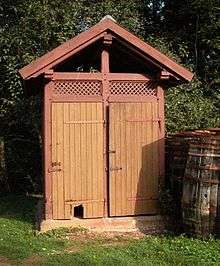

Outhouses vary in design and construction. Common features usually include:

- A separate structure from the main dwelling, close enough to allow easy access, but far enough to minimize odours.

- Being a suitable distance away from any freshwater well, so as to minimize risk of contamination and disease.[4]

- No connection to plumbing, sewer, or septic system.

- Walls and a roof for privacy and to shield the user from the elements—rain, wind, sleet and snow (depending on locale)—and thus to a small degree, cold weather. Floor plans typically are rectangular or square, but hexagonal outhouses have been built.[5] Thomas Jefferson designed and had built two brick octagons at his vacation home.[6]

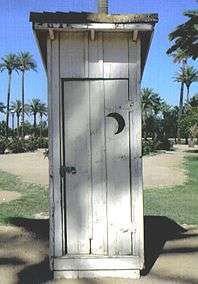

- There is no standard for outhouse door design. The well-known crescent moon on American outhouses was popularized by cartoonists and had a questionable basis in fact. There are authors who claim the practice began during the colonial period as an early "mens"/"ladies" designation for an illiterate populace (the sun and moon being popular symbols for the sexes during those times).[7] Others dismiss the claim as an urban legend.[upper-alpha 1] What is certain is that the purpose of the hole is for venting and light and there were a wide variety of shapes and placements employed.

- In Western societies, many, though not all, have at least one seat with a hole in it, above a small pit. Others, often in more rural, older areas in European countries, simply have a hole with two indents on either side for your feet.

- In Eastern societies, there is a hole in the floor, over which the user crouches.

- A roll of toilet paper is sometimes available. However, historically, old newspapers and catalogs from retailers specializing in mail order purchases, such as the Montgomery Ward or Sears Roebuck catalog, were also common before toilet paper was widely available. Paper was often kept in a can or other container to protect it from mice, etc. The catalogs served a dual purpose, also giving one something to read.[9] Old corn cobs, leaves, or other types of paper were also used.

- Outhouses are typically built on one level, but two-story models are to be found in unusual circumstances. One double-decker was built to serve a two-story building in Cedar Lake, Michigan. The outhouse was connected by walkways. It still stands (but not the building).[upper-alpha 2] The waste from "upstairs" is directed down a chute separate from the "downstairs" facility in these instances, so contrary to various jokes about two-story outhouses, the user of the lower level has nothing to fear if the upper level is in use at the same time.

- The Boston Exchange Coffee House (1809–1818) was equipped with a four-story outhouse[11] with windows on each floor[12]

- U.S. President Calvin Coolidge had a window in his outhouse, but such accoutrements are rare.[13]

- Outhouses are commonly humble and utilitarian, made of lumber or plywood. This is especially so they can easily be moved when the earthen pit fills up. Depending on the size of the pit and the amount of use, this can be fairly frequent, sometimes yearly. As pundit "Jackpine" Bob Cary wrote: "Anyone can build an outhouse, but not everyone can build a good outhouse."[14]

- However, brick outhouses are known. Some have been surprisingly ornate, almost opulent, considering the time and the place.[15] For example, an opulent 19th century antebellum example (a three-holer) is at the plantation area at the state park in Stone Mountain, Georgia.[16] The outhouses of Colonial Williamsburg varied widely, from simple expendable temporary wood structures to high-style brick.[6] See Jefferson's matched pair of eight-sided brick privies.[6] Such outhouses are sometimes considered to be overbuilt, impractical and ostentatious, giving rise to the simile "built like a brick shithouse." That phrase's meaning and application is subject to some debate; but (depending upon the country) it has been applied to men, women, or inanimate objects.

- Construction and maintenance of outhouses is subject to provincial, state, and local governmental restriction, regulation and prohibition.[17] It is potentially both a public health issue, which has been addressed both by law and by education of the public as to good methods and practices (e.g., separation from drinking water sources). This also becomes a more prevalent issue as urban and suburban development encroaches on rural areas,[18] and is an external manifestation of a deeper cultural conflict.[19] See also urban sprawl, urban planning, regional planning, suburbanization, urbanization and counterurbanization.

- Outhouses can be part of larger controversies concerning the environment, environmental policy, environmental quality and environmental law.[20]

- A modern analogy to the outhouse is the "Clivus Multrum", which is an electric and waterless composting toilet. They are an alternative to outhouses and septic fields, and provide effective sanitation in areas too remote for sewer lines. Worm hold privies, another variant of the composting toilet, are being touted by Vermont's Green Mountain Club. These simple outhouses are stocked with red worms (a staple used by home composters).[20] Despite their environmental benefits, composting toilets are likewise subject to regulations.[21]

- In suburban areas not connected to the sewerage, outhouses were not always built over pits. Instead, these areas utilized a pail closet, where waste was collected into large cans positioned under the toilet, to be collected by contractors (or night soil collectors) hired by property owners or the local council. The used cans were replaced with empty, cleaned cans. Until the 1970s Brisbane relied heavily on this form of sanitation.[22]

Biological processes

An outhouse is primarily a hole dug into the ground, into which biological waste solids and liquids are introduced, similar to a cesspit. If sufficient moisture is available, natural bacteria within the waste materials begin the process of fermentation. Earthworms, amoebas, molds, and other organisms in the surrounding ground soils, and flying insects entering the privy hole also consume nutrients in the waste material, slowly decomposing the wastes and forming a compost pile in the base of the pit. Bacteria form a complex biofilm on the wastes and in the surrounding exposed soils around the perimeter of the pit and feed on the wastes splashed or dropped into the pit.

An outhouse operates differently from a septic tank in that the pit is not normally filled with standing water. The solids act as a sponge to retain moisture but also are exposed to open air, allowing for insects and earthworms to feed on the wastes, which would not be possible within a septic tank. Septic tanks also tend to contain only organisms that can survive anaerobic conditions, while the open outhouse pit can sustain both aerobic and anaerobic organisms.

The process of decomposition is slow due to the layering of waste materials but is generally effective if the input of new wastes does not exceed the decomposition rate of the bacteria and other organisms. Small amounts of moisture from urination are absorbed by existing decomposed wastes in the base of the pit. In soils where the percolation rate of water through the soil is slow and where there is not a large amount of waste entering the pit, the wastes can slowly decompose and be rendered harmless without causing groundwater contamination.

In Scandinavia and some other countries, outhouses are built over removable containers that enable easy removal of the waste and enable much more rapid composting in separate piles.

Soil percolation and groundwater pollution

In soils with a fast rate of percolation, such as sandy soils, or where the base of the pit penetrates topsoils and clay going directly down to underlying gravel and fractured substone, waste liquids entering the unlined pit may quickly seep deep underground before bacteria and other organisms can remove contaminants, leading to groundwater pollution. This fast percolation of liquid wastes out of the pit can be slowed or prevented in newly dug outhouses by lining the base of the pit and the walls with a layer of absorptive organic material such as a thick mat of grass clippings. This material then decomposes and becomes part of the compost pile lining the pit that continues to act as a moisture sponge.

In most outhouse designs, the privy hole is covered by a small building. The primary purpose of the building is for privacy and human comfort, so that the user is not exposed and does not get wet when it is raining or cold when it is windy. However, the building has the secondary and (possibly unintended by the builder) effect of protecting the privy hole from large influxes of water when it is raining, which would flood the hole and flush untreated wastes into the underlying soils before they can decompose.

On flat or low-lying ground, the privy hole can be further protected from rain and floodwaters by constructing a small raised hill or berm around the edge of the hole, using material from the hole when the pit is first excavated, to raise the outhouse foundation. This helps falling rain and surface water to flow away from the sides of the outhouse so it does not enter the pit and lead to groundwater contamination.

Rain and surface water flowing into a low-lying open pit will also lead to soil erosion around the edges of the pit, that may eventually undermine the building foundation and potentially lead to collapse of the structure into the enlarging hole.

End of pit life

Eventually, over a period of many years, the solid wastes form a growing pile that fill the pit. A new pit is dug somewhere nearby, and soil obtained from digging the new pit is used to cover and cap off the old pit. Underground organisms such as earthworms continue decomposition of the old pit until the fecal material becomes indistinguishable from the surrounding ground soils.

High volume usage

In locations where an outhouse must serve a large number of users, the single pit may be extended to form a long covered trench or a series of separate pits, so that the waste inputs are spread out over a larger surface area. The fastest waste decomposition generally occurs in the uppermost layer of solids exposed to the air. Decomposition continues slowly in deeper layers but relies on diffusion of air into the solids to sustain life for the organisms within the solids.

A deeper pit may appear to provide additional capacity, but a thick layer of fresh solids deposited by many users may exceed the natural decomposition rate of the organisms in the pit, leading to increased potential for waste seepage out of the pit. A deep pit may also penetrate upper slow-percolation surface soil layers, and allow entry of contaminated waste liquids into the underlying fast percolation subsoils.

Decomposition may be accelerated by stirring or turning the pile, which breaks up the pile and introduces air pockets and air channels that allow faster organism growth within the bed of solids.

Holding tanks

In areas where an open pit cannot be safely constructed due to extremely high soil percolation rates and lack of absorptive organic material to absorb and decompose liquid wastes, the open pit can be replaced with a solid-walled storage tank, that typically must be pumped out regularly if water and waste matter is not permitted to leach out of the storage tank.

As opposed to a closed holding tank, a septic tank can be fashioned. The tank is fabricated so that waste water enters the first chamber of the tank, allowing solids to settle and scum to float. The settled solids are anaerobically digested, reducing the volume of solids. The liquid component flows through the dividing wall into the second chamber, where further settlement takes place, with the excess liquid just below the scum layer then draining in a relatively clean condition from the outlet into the leach field, also referred to as a drain field or seepage field.

If bacteria are added to the septic tank (as directed by the manufacturer), and no non-biodegradable matter (such as oil, grease, plastics, styrofoam, diapers, etc.) is flushed into the system, the waste matter will break down into its basic elements and the septic tank will operate trouble free for many years without the solid waste having to be pumped out.

As a sometimes beneficial consequence of trace amounts of waste matter making its way to the leach field, foliage will naturally flourish over the leach field, hence the phrase, "grass is always greener over the septic tank."

Hazardous waste

As with standard septic and sewage systems, toxic substances such as paint, oil, and chemicals must not be dumped into outhouse pits. The toxic materials will either kill the organisms breaking down the compost pile, or the chemicals may not be digestible, eventually seeping deeper underground and contaminating groundwater under the pit.

Odour

The decomposition of solids by organisms naturally leads to the emission of gases such as methane and hydrogen sulfide. These gases linger within the pit and are the source of the pit odor, but the open-pit nature permits diffusion of these gases out of the pit, so concentrations are typically low enough not to cause harm.

The odor can be reduced by installing a vertical vent tube in the corner of the outhouse structure. In the warmth of the day the vent tube is heated, which sets up a slow air convection current that draws fresh air into the privy hole, and expels warmed pit gases out the top of the vent tube.

Insect control

Some types of flying insects such as the housefly are attracted to the odor of decaying material, and will use it for food for their offspring, laying eggs in the decaying material. Other insects such as mosquitoes seek out standing water that may be present in the pit for the breeding of their offspring.

Both of these are undesirable pests to humans, but can be easily controlled without chemicals by enclosing the top of the pit with tight-fitting boards or concrete, using a privy hole cover that is closed after every use, and by using fine-grid insect screen to cover the inlet and outlet vent holes. This prevents flying insect entry by all potential routes.

Parasites

One of the purposes of outhouses is to avoid spreading parasites such as intestinal worms, notably hookworms, which might otherwise be spread via open defecation.

Controversies, trends and records

Outhouse design, placement, and maintenance has long been recognized as being important to the public health. See posters created by the Works Progress Administration.[23]

The growing popularity of paddling, hiking, and climbing has created special waste disposal issues throughout the world. It is a dominant topic for outdoor organizations and their members.[20]

- On August 29, 2007, the highest outhouse (actually, not a building at all, but a pit toilet surrounded by a low rock wall) in the continental United States, which sat atop Mount Whitney at about 14,494 feet (4,418 m) above sea level, offering a magnificent panorama to the user, was removed. Two other outhouses, in the Inyo National Forest, were closed due to the expense and danger involved in transporting out large sewage drums via helicopter. The annual 19,000 or so hikers of the Mount Whitney Trail, who must pick up National Forest Service permits, are now given Wagbags (a double-sealed sanitation kit) and told how to use them. "Pack it in; pack it out" is the new watchword.[24] Solar-powered toilets did not sufficiently compact the excrement, and the systems were judged failures at that location. Additionally, by relieving park rangers of latrine duty, they were better able to concentrate on primary ranger duties, e.g., talking to hikers.[25] The use of Wagbags and the removal of outhouses is part of a larger trend in U.S. parks.[24]

- In 2007, Europe's two highest outhouses were helicoptered to the top of France's Mont Blanc at a height of 4,260 metres (13,980 ft). The dunny-cans are emptied by helicopter. The facilities will serve 30,000 skiers and hikers annually, thus helping to alleviate the deposit of urine and feces that spread down the mountain face with the spring thaw, and turned it into 'Mont Noir'.[26] More technically, the 2002 book Le versant noir du mont Blanc ("The black hillside of Mont Blanc") exposes problems in conserving the site.[27]

- Upon the 5,642-metre (18,510 ft) Mount Elbrus—Russia's highest peak, the highest mountain in all of Europe and topographically dividing Europe from Asia—sits the world's "nastiest outhouse" at 4,206 metres (13,799 ft). It is in the Caucasus Mountains, near the frontier between Georgia and Russia. As one writer opined, "...it does not much feel like Europe when you're there. It feels more like Central Asia or the Middle East."[28][29] The outhouse is surrounded by and covered in ice, perched off the end of a rock, and with a pipe pouring effluvia onto the mountain. It consistently receives low marks for sanitation and convenience, but is considered to be a unique experience.[30]

- Australia's highest "dunny"—located at Rawson's Pass in the Main Range in Kosciuszko National Park, which each year receives more than 100,000 walkers outside of winter and has a serious human waste management issue, was completed in 2008.[31]

- A stone outhouse in Colca Canyon, Peru, has been claimed to be "the world's highest".[32]

- Many reports document the use of dunny cans (complete with pictures) for the removal of excrement, which must be packed in and packed out on Mount Everest. Also known as "expedition barrels"[33] or "bog barrels",[34] the cans are weighed to make sure that groups do not dump them along the way.[35] "Toilet tents" are erected.[36][37] This would seem to be an improvement over the prior practices, including the so-called "McKinley system"; there has been an increasing awareness that the mountain needs to be kept clean, for the health of the climbers at least.[33]

- A Norwegian invention challenges the conventional outhouse. The toilet incinerates waste into ashes, using only propane and 12 V DC. This incinerating toilet is installed in several thousand cabins in Norway.[38]

- The Swedish Pacto toilet uses a continuous roll of plastic to collect and dispose of waste.[39]

Society and culture

- The double-decker outhouse has been used as an unflattering metaphor for the "Trickle-down theory" of politics, economics, command, management, labor relations, responsibility, etc.[40][41] Depending on who is depicted on top and below, it is an easy and familiar cartoon.[42]

- On November 10, 2003, a drawing of an outhouse was used by B.C. cartoonist Johnny Hart as a motif in a controversial and allegedly religiously-themed piece.[43] The cartoonist denied the allegations and the convoluted analysis of the alleged iconography of the cartoon.

- In Michigan, the Upper Peninsula's Trenary has the largest outhouse race,[44][45] but Mackinaw City is home to an annual and largest "outhouse race south of the Mackinac Bridge".[46] Other famous outhouse races are during the Yale Bologna Festival and in Dawson City, Yukon.

- Charles "Chic" Sale was a famous comedian in vaudeville and the movies. In 1929 he published a small book, The Specialist,[47] which was a hugely popular "underground" success. Its entire premise centered on sales of outhouses, touting the advantages of one kind or another, and labeling them in "technical" terms such as "one-holers", "two-holers", etc. Over a million copies were sold. In 1931 his monologue "I'm a Specialist"[48] was made into a hit record (Victor 22859) by popular recording artist Frank Crumit (music by Nels Bitterman). As memorialized in the "Outhouse Wall of Fame",[49] the term "Chic Sale" became a rural slang synonym for privies, an appropriation of Mr. Sale's name that he personally considered unfortunate. (See Outhouse humor.)

- Folk singer Billy Edd Wheeler wrote and performed a song titled "The Little Brown Shack Out Back", a sentimental look at the outhouse.[50]

- In Newfoundland, a well-known song entitled "Good Old Newfie Outhouse" sings the praises of using the outhouse when it is -25 degrees out, mentioning pleasures like pants being frozen in position at the knees. A version by singer Bobby Evans is available on an album called Silly Songs on iTunes.[51]

- The U.S. National Park Service once built an outhouse that cost above $333,000.[52]

- As a college student, Richard Nixon achieved renown by providing a three-hole outhouse to be tossed onto the traditional campus bonfire.[53]

- Tsi-Ku, also known as Tsi Ku Niang, is described as the Chinese goddess of the outhouse and divination. It is said that a woman could uncover the future by going to the outhouse to ask Tsi-Ku.[54][55]

- Old outhouse pits are seen as excellent places for archeological and anthropological excavations, offering up a trove of common objects from the past—a veritable inadvertent time capsule—which yields historical insight into the lives of the bygone occupants. It is especially common to find old bottles, which seemingly were secretly stashed or trashed, so their content could be privately imbibed.[4][56]

-

Outhouse in the mountains in northern Norway

-

Outhouse used by sharecroppers on display, Louisiana State Cotton Museum, Lake Providence

-

A brick outhouse at Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest estate near Lynchburg, Virginia

-

Example of an outhouse used in the 19th century American Southwest. This one is in the Manistee Ranch in Glendale, Arizona.

-

Another example of an outhouse used in the 19th century American Southwest. This one is in the Sahuaro Ranch in Glendale, Arizona.

-

Eight-seat stone outhouse at the Thomas Leiper Estate near Wallingford, Pennsylvania

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Discussion of outhouses as vernacular architecture (including crescent moon folklore), from the Missouri Folklore Society.[8]

- ↑ 7620 N. Academy Rd, Cedar Lake, Michigan.[10]

Citations

- ↑ "Plans for a five-holer at Sewer History". Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ "ShowUsYourLongDrop.co.nz". Showusyourlongdrop.co.nz. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

This website has been set up to showcase all the creative Long Drops that are popping up around Christchurch, New Zealand (improvised after the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake)

- ↑ "KYBO". Scoutorama.com. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- 1 2 Martin, Douglas (August 29, 1996). "An Outhouse in SoHo Yields Artifacts of 19th century Life - New York Times". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Sewer History: Photos and Graphics".

- 1 2 3 Olmert, Michael. "Necessary and Sufficient". Colonial Williamsburg Journal. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Adams, Cecil (January 9, 1987). "The Straight Dope: Why do outhouse doors have half-moons on them?".

- ↑ "Missouri Outhouses". Missouri Folklore Society. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ "PortalWisconsin.org – Chat".

- ↑ "Cedar Lake, MI - Two-Story Outhouse".

- ↑ Bahne, Charles (2012). Chronicles of Old Boston: Exploring New England's Historic Capital (print). New York: Museyon, Signature Book Services distributor. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-9846334-0-1.

- ↑ Kamensky, Jane (2008). The Exchange Artist: A Tale of High-Flying Speculation and America's First Banking Collapse (print). New York: Viking Press/Penguin Books. p. 184. ISBN 978-0670018413.

- ↑ "Coolidge outhouse with window, picture".

- ↑ Cary, "Jackpine" Bob (2003). The All-American Outhouse–Stories, Design & Construction (print). Cambridge, MN: Adventure Publications. ISBN 978-1-59193-011-2.

- ↑ "Sewer History: Photos and Graphics".

- ↑ Nichols, A. (February 28, 1998). "Georgia's Stone Mountain Brick Outhouse". Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Reilly, Mike (December 18, 2005) [February 19, 1997]. "The World & Milwaukee Early Sanitation History - Outhouses, Privies, Scavengers & Sewers or Privileged Privy Prattle". Privy Vaults: Early Milwaukee Sanitation History. Sussex-Lisbon Historical Society, Inc.

- ↑ "Among the Outhouses, the Prospect of Plumbing; Change, Not Sought by All, May Be in the Pipeline for a Rustic Westchester Niche - New York Times". The New York Times. December 1, 1997. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Kentucky Amish-Mennonite schools accused of violating health regulations". U.S. Water & News. January 1, 2003. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Motavalli, Jim (1998). "Flushed with success: new waste-reducing design in modern toiletry". E: The Environmental Magazine.

- ↑ 'See Composting toilets bring the outhouse indoors — JSCMS Archived August 17, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Observations « Carry the Bags".

- ↑ "Library of Congress, American Memory Historical Collections for the National Digital Library, Reproduction Number LC-USZC2-1592 DLC.".

- 1 2 Barringer, Felicity (September 5, 2007). "No More Privies, So Hikers Add a Carry-Along". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ "FresnoBee.com: Outdoors: A new approach to Whitney's waste". Fresno Bee.

- ↑ "Europe's highest toilet". Ananova. 1989-04-15. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ proMONT-BLANC Le versant noir du Mont-Blanc. Archived December 8, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Outside Magazine 1993 search and article)

- ↑ Flinn, John (August 28, 2010). "The pinnacle of success - and disgust - for climbers". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ See "Getting to the Top in the Caucasus" - New York Times

- ↑ "Kosciuszko National Park Plan of Management: 2006-2007 Implementation Report" (PDF). National Parks and Wildlife Service. 2006. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ "ideotrope | Peru07: Colca Canyon".

- 1 2 "MountainZone.com".

- ↑ "Mt. Everest 2005: The British Everest expedition reports 7 Summits from the North!".

- ↑ "BBC | Horizon on Everest".

- ↑ "Paul & Fi's Mount Everest Climb".

- ↑ "Adventure Peaks Mt Everest 2004 Expedition".

- ↑ "Cinderella Gas".

- ↑ "Pacto Toilet".

- ↑ "American Chronicle: A Well Deserved Death for Trickle-Down"

- ↑ Hyde, Kevin. "Dr. Phil Is Leaving the Building". U of L Journal. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ "The Two Story Outhouse!".

- ↑ Weingarten, Gene (November 21, 2003). "Cartoon Raises a Stink: Some See Slur Against Islam in a 'B.C.' Outhouse Strip". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ↑ Packard, Mary (September 2004). Ripley's Believe It or Not! (hardcover print). New York: Scholastic. ISBN 0-439-46553-2.

- ↑ "The Annual Outhouse Races in Northern Michigan".

- ↑ "Google Image, Mackinaw Outhouse race". Mackinawouthouserace.com. 2012-01-21. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ ISBN 0-285-63226-4

- ↑ Sale, Charles (Chic); Kermode, William (illustrator) (1994) [1929]. "The Specialist" (print). London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-63226-4. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Specialist". Outhouse Wall of Fame. Outhouse Museum. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016.

- ↑ Wheeler, Billy Edd. "That Little Old Shack Out Back" (audio). Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Nolan, Dick. "Song Titles by Album". Dick Nolan. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ Greve, Frank (October 8, 1997). "The Opulent Outhouse". The Seattle Times (Delaware Water Gap, Pennsylvania: Knight-Ridder Newspapers). Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ People's Almanac, Wallechinsky & Wallace.

- ↑ FireyOn. "The Gods and Goddesses of China". Gods and Goddesses of the World. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Monaghan, Patricia; Mullane Literary Agency (editor) (December 2009). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines. Santa Barbara, California: Heinemann Educational Books. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-313-34989-8. ISBN 0-313-34989-4.

- ↑ Compare "What are Outhouse Diggers?". Outhouse Tour of America Tour. January 18, 1998. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

Literature and further reading

- Booth, Dottie (1998). Nature Calls: The History, Lore, and Charm of Outhouses (print). Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-0-89815-990-5.

- Barlow, Ronald S. (1992). The Vanishing American Outhouse: A History of Country Plumbing (print). El Cajon, California: Windmill Publishing. ISBN 0-933846-02-9.

- Cary, "Jackpine" Bob (2003). The All-American Outhouse–Stories, Design & Construction (print). Cambridge, MN: Adventure Publications. ISBN 978-1-59193-011-2.

- Morna E., Gregory; Sian, James (2006). Toilets of the World (paperback). London: Merrell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1-85894-337-X. ISBN 978-1-85894-337-4.

- Harrison, Peter Joel (2002). Garden Houses and Privies, Authentic Details for Design and Restoration (print). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-20332-7. Member of the Outhouse Wall of Fame[1]

- Roberts, J. Aelwyn (2002). Privies of Wales (paperback). Llandegai, Bangor: Tegai Publications. ISBN 0-9539494-0-0.

- Safron, Helena (2009). Memorializing the Backhouse: Sanitizing and Satirizing Outhouses in the American South (MA thesis). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. p. 219.

- Sale, Charles (Chic); Kermode, William (Illustrator) (1994) [1929]. "The Specialist" (print). London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-63226-4. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Outhouse. |

- Example of a twelve-family outhouse from St. Louis, MO, 1910

- Schladweiler, Jon; McDonald, Jan; Matty, Paul; Siva, Stephanie (January 20, 2011). "Sewer History: Photos and Graphics (Historical graphics, photos, and plans for outhouses)". Tracking Down the Roots of Our Sanitary Sewers. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- Olmert, Michael. "Necessary and Sufficient". Colonial Williamsburg Journal. Retrieved November 27, 2014. (article about outhouses in colonial America)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||