Three-body problem

In physics and classical mechanics, the three-body problem is the problem of taking an initial set of data that specifies the positions, masses and velocities of three bodies for some particular point in time and then determining the motions of the three bodies, in accordance with the laws of classical mechanics (Newton's laws of motion and of universal gravitation). The three-body problem is a special case of the n-body problem.

Historically, the first specific three-body problem to receive extended study was the one involving the Moon, the Earth and the Sun.[1] In an extended modern sense, a three-body problem is a class of problems in classical or quantum mechanics that model the motion of three particles.

History

The gravitational problem of three bodies in its traditional sense dates in substance from 1687, when Isaac Newton published his "Principia" (Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica). In Proposition 66 of Book 1 of the "Principia", and its 22 Corollaries, Newton took the first steps in the definition and study of the problem of the movements of three massive bodies subject to their mutually perturbing gravitational attractions. In Propositions 25 to 35 of Book 3, Newton also took the first steps in applying his results of Proposition 66 to the lunar theory, the motion of the Moon under the gravitational influence of the Earth and the Sun.

The problem became of technical importance in the 1720s, as an accurate solution would be applicable to navigation, specifically for the determination of longitude at sea. This problem was addressed by Amerigo Vespucci and by Galileo Galilei before being solved by John Harrison's invention of the Marine chronometer. Before the chronometer became available, Vespucci had used, in 1499, knowledge of the position of the moon to determine his position in Brazil. However the accuracy of the lunar theory was low, due to the perturbing effect of the Sun, and planets, on the motion of the Moon around the Earth.

Jean d'Alembert and Alexis Clairaut, who developed a longstanding rivalry, both attempted to analyze the problem in some degree of generality, and by the use of differential equations to be solved by successive approximations. They submitted their competing first analyses to the Académie Royale des Sciences in 1747.[2]

It was in connection with these researches, in Paris, in the 1740s, that the name "three-body problem" (Problème des Trois Corps) began to be commonly used. An account published in 1761 by Jean d'Alembert indicates that the name was first used in 1747.[3]

In 1887, mathematicians Heinrich Bruns[4] and Henri Poincaré showed that there is no general analytical solution for the three-body problem given by algebraic expressions and integrals. The motion of three bodies is generally non-repeating, except in special cases.[5]

Examples

Gravitational systems

A prominent example of the classical three-body problem is the movement of a planet with a satellite around a star. In most cases such a system can be factorized, considering the movement of the complex system (planet and satellite) around a star as a single particle; then, considering the movement of the satellite around the planet, neglecting the movement around the star. In this case, the problem is simplified to the two-body problem. However, the effect of the star on the movement of the satellite around the planet can be considered as a perturbation.

A three-body problem also arises from the situation of a spacecraft and two relevant celestial bodies, e.g. the Earth and the Moon, such as when considering a free return trajectory around the Moon, or other trans-lunar injection. While a spaceflight involving a gravity assist tends to be at least a four-body problem (spacecraft, Earth, Sun, Moon), once far away from the Earth when Earth's gravity becomes negligible, it is approximately a three-body problem.

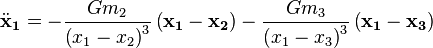

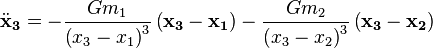

The general statement for the three body problem is as follows. At an instant in time, for vector positions  and masses

and masses  , three coupled second-order differential equations exist:

, three coupled second-order differential equations exist:

A complete solution for a particular three-body problem provides the positions for all three particles for all time given three initial positions and initial velocities.

Circular restricted three-body problem

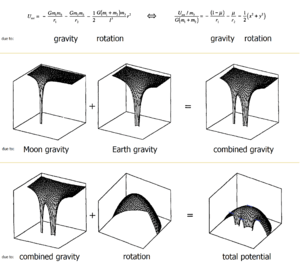

In the circular restricted three-body problem, two massive bodies move in circular orbits around their common center of mass, and the third mass is negligible with respect to the other two.[6] With respect to a rotating reference frame, the two co-orbiting bodies are stationary, and the third can be stationary as well at the Lagrangian points, or orbit around them, for instance on a horseshoe orbit. It can be useful to consider the effective potential.

Periodic solutions

In 1767 Leonhard Euler found three families of periodic solutions in which the three masses are collinear at each instant. In 1772 Lagrange found a family of solutions in which the three masses form an equilateral triangle at each instant. Together, these solutions form the central configurations for the three-body problem. These solutions are valid for any mass ratios, and the masses move on Keplerian ellipses. These five families are the only known solutions for which we have explicit analytic formulae. In the special case of the circular restricted three-body problem, these solutions, viewed in a frame rotating with the primaries, become points which are referred to as L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5 and called Lagrangian points .

Additional solutions

In work summarized in 1892-1899, Henri Poincaré established the existence of an infinite number of periodic solutions to the restricted three-body problem, and established techniques for continuing these solutions into the honest three-body problem.

In 1893 Meissel stated what is nowadays called the Pythagorean three-body problem: three masses in the ratio 3:4:5 are placed at rest at the vertices of a 3:4:5 triangle. Burrau [7] further investigated this problem in 1913. In 1967 Victor Szebehely and coworkers established eventual escape for this problem using numerical integration, while at the same time finding a nearby periodic solution.

In 1911, United States Scientist William Duncan MacMillan found one special solution. In 1961, Russian mathematician Sitnikov improved this problem. See Sitnikov problem.

In the 1970's Michel Hénon and R. Broucke each found a set of solutions which form part of the same family of solutions: the Broucke-Henon-Hadjidemetriou family. In this family the three objects all have the same mass and can exhibit both retrograde and direct forms. In some of Broucke solutions two of the bodies follow the same path.[8]

In 1993 a solution with three equal masses moving around a figure-eight shape was discovered by physicist Cris Moore at the Santa Fe Institute. This solution has zero total angular momentum.

In 2013, physicists Milovan Šuvakov and Veljko Dmitrašinović at the Institute of Physics in Belgrade discovered 13 new families of solutions for the equal mass zero angular momentum three body problem.[5][8]

Classical versus quantum mechanics

Physicist Vladimir Krivchenkov used the three-body problem as an example, showing the simplicity of quantum mechanics in comparison to classical mechanics. The quantum three-body problem is studied in university courses of quantum mechanics.[9] For a special case of the quantum three-body problem known as the hydrogen molecular ion, the eigenenergies are solvable analytically (see discussion in quantum mechanical version of Euler's three-body problem) in terms of a generalization of the Lambert W function.

However this is possible only by taking certain assumptions which basically reduce the problem to a single-body problem within an energy potential. Generally even a two-body problem is not solvable analytically in quantum mechanics, since there is usually no analytical solution to the multi-particle Schrödinger partial differential equation. Some mathematical research in quantum mechanics is still dedicated either to finding a good numerical solution [10] or finding ways to reduce the problem into a more simple system that can be solved analytically such as the Hartree–Fock method and the Franck–Condon principle.

Sundman's theorem

In 1912, the Finnish mathematician Karl Fritiof Sundman proved there exists a series solution in powers of t1/3 for the 3-body problem.[11] This series is convergent for all real t, except initial data that correspond to zero angular momentum. However, these initial data are not generic since they have Lebesgue measure zero.

An important issue in proving this result is the fact that the radius of convergence for this series is determined by the distance to the nearest singularity. Therefore it is necessary to study the possible singularities of the 3-body problems. As it will be briefly discussed below, the only singularities in the 3-body problem are binary collisions (collisions between two particles at an instant), and triple collisions (collisions between three particles at an instant).

Now collisions, whether binary or triple (in fact any number), are somehow improbable—since it has been shown they correspond to a set of initial data of measure zero. However, there is no criterion known to be put on the initial state in order to avoid collisions for the corresponding solution. So, Sundman's strategy consisted of the following steps:

- Using an appropriate change of variables, to continue analyzing the solution beyond the binary collision, in a process known as regularization.

- Prove that triple collisions only occur when the angular momentum L vanishes. By restricting the initial data to L ≠ 0 he removed all real singularities from the transformed equations for the 3-body problem.

- Showing that if L ≠ 0, then not only can there be no triple collision, but the system is strictly bounded away from a triple collision. This implies, by using Cauchy's existence theorem for differential equations, there are no complex singularities in a strip (depending on the value of L) in the complex plane centered around the real axis (shades of Kovalevskaya).

- Find a conformal transformation that maps this strip into the unit disc. For example if s = t1/3 (the new variable after the regularization) and if

then this map is given by:

then this map is given by:

This finishes the proof of Sundman's theorem.

Unfortunately the corresponding convergent series converges very slowly. That is, getting the value to any useful precision requires so many terms, that his solution is of little practical use. Indeed, in 1930 David Beloriszky calculated that if Sundman’s series were going to be used for astronomical observations then the computations would involve at least  terms.[12]

terms.[12]

n-body problem

The three-body problem is a special case of the n-body problem, which describes how n objects will move under one of the physical forces, such as gravity. These problems have a global analytical solution in the form of a convergent power series, as was proven by Sundman for n = 3 and by Wang for n > 3 (see n-body problem for details). However, the Sundman and Wang series converge so slowly that they are useless for practical purposes;[13] therefore, it is currently necessary to approximate solutions by numerical analysis in the form of numerical integration or, for some cases, classical trigonometric series approximations (see n-body simulation). Atomic systems, e.g. atoms, ions, and molecules, can be treated in terms of the quantum n-body problem. Among classical physical systems, the n-body problem usually refers to a galaxy or to a cluster of galaxies; planetary systems, such as star(s), planets, and their satellites, can also be treated as n-body systems. Some applications are conveniently treated by perturbation theory, in which the system is considered as a two-body problem plus additional forces causing deviations from a hypothetical unperturbed two-body trajectory.

See also

- Michael Minovitch

- Gravity assist

- Euler's three-body problem

- Few-body systems

- n-body simulation

- Galaxy formation and evolution

- Triple star system

- de:Sitnikov-Problem

Notes

- ↑ "Historical Notes: Three-Body Problem". Retrieved December 2010.

- ↑ The 1747 memoirs of both parties can be read in the volume of Histoires (including Mémoires) of the Académie Royale des Sciences for 1745 (belatedly published in Paris in 1749) (in French):

- Clairaut: "On the System of the World, according to the principles of Universal Gravitation" (at pp. 329–364); and

- d'Alembert: "General method for determining the orbits and the movements of all the planets, taking into account their mutual actions" (at pp. 365–390).

- The peculiar dating is explained by a note printed on page 390 of the 'Memoirs' section:"Even though the preceding memoirs, of Messrs. Clairaut and d'Alembert, were only read during the course of 1747, it was judged appropriate to publish them in the volume for this year" (i.e. the volume otherwise dedicated to the proceedings of 1745, but published in 1749).

- ↑ Jean d'Alembert, in a paper of 1761 reviewing the mathematical history of the problem, mentions that Euler had given a method for integrating a certain differential equation "in 1740 (seven years before there was question of the Problem of Three Bodies)": see d'Alembert, "Opuscules Mathématiques", vol.2, Paris 1761, Quatorzième Mémoire ("Réflexions sur le Problème des trois Corps, avec de Nouvelles Tables de la Lune ...") pp. 329–312, at sec. VI, p. 245.

- ↑ J J O'Connor & E F Robertson (August 2006). "Bruns biography". University of St. Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- 1 2 Jon Cartwright (8 March 2013). "Physicists Discover a Whopping 13 New Solutions to Three-Body Problem". Science Now. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ↑ Restricted Three-Body Problem, Science World.

- ↑ Burrau. "Burrau".

- 1 2 M. Šuvakov; V. Dmitrašinović. "Three-body Gallery". Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ Gol’dman, I. I.; Krivchenkov, V. D. (2006). Problems in Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.). Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486453227.

- ↑ H. Parsian and R. Sabzpoushan, "Two Particles Problem in Quantum Mechanics" , Adv. Studies Theor. Phys., Vol. 7, 2013, no. 13, 621 - 627, doi: 10.12988/astp.2013.3432

- ↑ Barrow-Green, J. (2010). The dramatic episode of Sundman, Historia Mathematica 37, pp. 164–203.

- ↑ Beloriszky, D. 1930. Application pratique des méthodes de M. Sundman à un cas particulier du problème des trois corps. Bulletin Astronomique 6 (series 2), 417–434.

- ↑ Diacu, Florin. "The Solution of the n-body Problem*", The Mathematical Intelligencer, 1996.

References

- Poincaré, H. (1967). New Methods of Celestial Mechanics, 3 vols. (English trans.). American Institute of Physics. ISBN 1-56396-117-2.

- Aarseth, S. J. (2003). Gravitational n-Body Simulations. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43272-3.

- Bagla, J. S. (2005). "Cosmological N-body simulation: Techniques, scope and status". Current Science 88: 1088–1100. arXiv:astro-ph/0411043. Bibcode:2005CSci...88.1088B.

- Chambers, J. E.; Wetherill, G. W. (1998). "Making the Terrestrial Planets: N-Body Integrations of Planetary Embryos in Three Dimensions". Icarus 136 (2): 304–327. Bibcode:1998Icar..136..304C. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.6007.

- Efstathiou, G.; Davis, M.; White, S. D. M.; Frenk, C. S. (1985). "Numerical techniques for large cosmological N-body simulations". ApJ 57: 241–260. Bibcode:1985ApJS...57..241E. doi:10.1086/191003.

- Hulkower, Neal D. (1978). "The Zero Energy Three Body Problem". IUMJ 27: 409–447. Bibcode:1978IUMJ...27..409H. doi:10.1512/iumj.1978.27.27030.

- Hulkower, Neal D. (1980). "Central Configurations and Hyperbolic-Elliptic Motion in the Three-Body Problem". Celestial Mechanics 21 (1): 37–41. Bibcode:1980CeMec..21...37H. doi:10.1007/BF01230244.

- Moore, Cristopher (1993), "Braids in classical dynamics" (PDF), Physical Review Letters 70 (24): 3675–3679, Bibcode:1993PhRvL..70.3675M, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.3675, PMID 10053934.

- Šuvakov, Milovan; Dmitrašinović, V. (2013). "Three Classes of Newtonian Three-Body Planar Periodic Orbits". Phys. Rev. Lett. 110 (10): 114301. arXiv:1303.0181. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110k4301S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.114301.

- Li, Xiaoming; Liao, Shijun (2014). "On the stability of the three classes of Newtonian three-body planar periodic orbits". Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 57 (11): 2121–2126. arXiv:1312.6796. Bibcode:2014SCPMA..57.2121L. doi:10.1007/s11433-014-5563-5.

In popular culture

- The three-body problem is represented as a set of equations on the blackboard of Professor Barnhardt in the movie The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951).

- "The Three-Body Problem" is both the title and the topic of a science fiction book by Chinese author Cixin Liu

External links

- Chenciner, Alain (2007). "Three body problem" 2 (10). Scholarpedia: 2111. Retrieved 2009-12-18.