Early life of Pedro II of Brazil

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The early life of Pedro II of Brazil covers the period from his birth on 2 December 1825 until 18 July 1841, when he was crowned and consecrated. Born in Rio de Janeiro, the Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II was the youngest and only surviving male child of Dom Pedro I, first emperor of Brazil, and his wife Dona Leopoldina, archduchess of Austria. From birth, he was heir to his father's throne and was styled Prince Imperial. As member of the Brazilian Royalty, he held the honorific title "Dom".[1]

Pedro II's mother died when he was one year old, and his father remarried, to Amélie of Leuchtenberg, a couple years later. Pedro II formed a strong bond with Empress Amélie, whom he considered to be his mother throughout the remainder of his life. When Pedro I abdicated on 7 April 1831 and departed to Europe with Amélie, Pedro II was left behind with his sisters and became the second emperor of Brazil. He was raised with simplicity but received an exceptional education towards shaping what Brazilians then considered an ideal ruler. The sudden and traumatic loss of his parents, coupled with a lonely and unhappy upbringing, greatly affected Pedro II and shaped his character.

When he ascended to the throne, Pedro II was only five years old. Until he came of age and would be able to exert his constitutional powers, a regency was created. It proved to be weak and to have little effective authority, which led the nation into anarchy, ravaged by political faction struggles and countless rebellions. Exploited as a tool by rival political factions in pursuit of their own interests, Pedro II was manipulated into accepting an early elevation to majority status on 22 July 1840 at age 14, thus putting an end to nine years of chaotic regency rule.

Heir to the throne

Birth

Pedro de Alcântara João Carlos Leopoldo Salvador Bibiano Francisco Xavier de Paula Leocádio Miguel Gabriel Rafael Gonzaga[2][3][4][5] was born following a childbirth that lasted for more than five hours at 2:30 a.m. on 2 December 1825.[6][7][8] His name, as well as his father's, was a homage to St. Peter of Alcantara.[9][10]

Through his father, Emperor Pedro I, he was a member of the Brazilian branch of the House of Braganza. This, in turn, was an illegitimate branch of the Capetian dynasty. He was thus grandson of João VI and nephew of Miguel I.[11][12] His mother was the Archduchess Maria Leopoldina, daughter of Francis II, last Holy Roman Emperor. Through his mother he was a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte and first cousin of Emperors Napoleon II of France, Franz Joseph I of Austria and Maximilian I of Mexico.[12][13][14][15] Among his ancestors, it can be cited Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King Louis XIV of France.[13]

On the day of his birth Pedro was presented by Brigadier General Francisco de Lima e Silva, the Empress' veador (gentleman usher) to members of the Brazilian government assembled at the Paço de São Cristóvão (Palace of Saint Christopher), home of the Imperial family.[4][6][16] He was only 47 centimeters tall[17] and was considered a fragile and sickly child. He had inherited the epilepsy of the Spanish Bourbons,[18][19] although this would completely disappear at adolescence.[20] He was baptized a few days later on 9 December.[4][13][17] His elder sister Maria was godmother,[3] and his father was named as his godfather.[11]

Having been born after the recognition of Brazilian independence, he was considered a foreigner under Portuguese law.[21] However, his elder sister, having been born prior to independence, was able to ascend the throne of Portugal as Maria II upon the abdication of their father (Pedro I, who was also Pedro IV of Portugal) on 28 May 1826.[22] As the only legitimate male child of Pedro I to survive infancy, he became heir to his father's Brazilian crown as Prince Imperial and was officially recognized as such on 6 August 1826.[3][23]

Early years

Pedro I invited Dona Mariana de Verna Magalhães Coutinho (later Countess of Belmonte in 1844) to take the position of aia (supervisor) to his son.[23][24] Mariana de Verna was a Portuguese widow who was considered a cultured, honorable and kindly woman.[19][23][25] Pedro II called her "Dadama" as he did not pronounce the word "dame" correctly as a child.[23] However, he would continue calling her in this way into adulthood, though out of affection and treating her as his surrogate mother.[3][6][19][23][26] As was the custom of the time, he was not nursed by his mother. Instead, a Swiss immigrant from the Morro do Queimado colony ("Burnt Hill", now Nova Friburgo) by the name of Marie Catherine Equey[lower-alpha 1] was chosen as his wet nurse.[17]

Empress Leopoldina died on 11 December 1826, days after the stillbirth of a male child,[27][28] when Pedro was one year old.[15][19][22] Pedro would have no memory of his mother; only what he was later told about her.[19][29] Of his father, "he retained no strong images of him" in adulthood,[30] that is, he recalled "no clear visual image" of Pedro I.[31]

His father was married two and a half years later to Amélie of Leuchtenberg. Prince Pedro spent little time with his stepmother, who would ultimately leave the country two years later. Even so, they had an affectionate relationship[28][32][33] and kept in contact with each other until her death in 1873.[34] So strong was Amélie's influence over the young prince that he always considered her to be his mother, and as an adult "the ideal female, whom he ever sought, was dark-haired, vivacious, and intelligent, and noticeably older in years than he."[35] Pedro I abdicated the Imperial crown on 7 April 1831, after a long conflict with the federalist liberals. He and Amélie immediately departed for Portugal to reclaim the crown of his daughter, which had been usurped by his brother Miguel I.[36][37] Left behind, Prince Imperial Pedro thus became "Dom Pedro II, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil".[lower-alpha 2][8][38]

The Regency

Accession

When the five-year-old Pedro awoke on 7 April 1831, beside him on the bed lay his father's imperial crown.[39] Pedro I and his wife[40] had already left Brazilian soil and boarded the British frigate Warspite. Pedro II wrote a letter of farewell to his father aided by Mariana de Verna.[39] On receipt of this, a tearful Pedro I composed a reply, calling the little boy "My beloved son, and my Emperor."[39][41] His father and stepmother remained on board the Warspite another five days before leaving for Europe, but they did not see the young emperor during that period … or ever again.[42] For the remainder of his life, Pedro I would become distressed upon his children's absences and fretted about their futures. Pedro II missed his father and stepmother (who had assumed his mother's role), and this may account for his later lack of any emotional display in public.[40] In fact, the "sudden loss of his family was to haunt Pedro II throughout his life".[31] Three of his sisters stayed behind in Brazil with Pedro II: Januária, Paula and Francisca.[43]

Pedro II was acclaimed as the new Brazilian Emperor on 9 April.[38] Bewildered by his parents' abandonment and frightened by the large crowds and thundering artillery salutes, he wept inconsolably as he was taken, with Mariana de Verna at his side, by carriage up to the City Palace.[39][41] The frightened young Emperor was displayed along with his sisters at one of the windows of the palace. He stood atop a chair so that he could be seen by the assembled thousands and observe their acclamations.[39][44] The Brazilians were touched by this "figure of a small orphan who would rule them one day."[45] The entire ordeal, followed by the roar of saluting cannon, was so traumatic to the little emperor that it may account for his noted aversion to ceremonies as an adult.[46]

His elevation as emperor ushered in a period of crisis, the most troublesome in Brazil's history.[47] As Pedro II could not exert his constitutional prerogatives as Emperor (Executive and Moderating Power) until he reached majority, a regency was created. The first regency consisted of a triumvirate, and one of its members was the same Brigadier General Francisco de Lima e Silva who had presented the infant Pedro to the Government more than five years previously.[36] Disputes between political factions resulted in an unstable, almost anarchical, regency. The Liberals who had ousted Pedro I soon split into two factions: moderate liberals (constitutional monarchists who would later split into the Liberal Party and Conservative Party)[48] and Republicans (a small minority, but radical and highly rebellious).[49] There were also the Restorationists who had been previously known as Bonifacians.[49]

Several rebellions erupted during the regency.[50] The first were the Rebellion of Santa Rita (1831),[51] the Revolt of the Year of the Smoke (1833)[52] and the Cabanada (or War of the Cabanos, 1832–34),[53][54] which sought the return of Pedro I and which had the support of common people, former slaves, and slaves.[55][56] The death of Pedro I on 24 September 1834[57] ended their hopes.[48][58] The promulgation of the Additional Act in 1834, a constitutional amendment that gave higher administrative and political provincial decentralization, exacerbated conflicts between political parties, as whichever dominated the provinces would also gain control over the electoral and political system. Those parties which lost elections rebelled and tried to assume power by force.[59] Rebellious factions, however, continued to uphold the Throne as a way of giving the appearance of legitimacy to their actions (that is, they were not in revolt against the monarchy per se). The Cabanagem (1835–40),[53] the Sabinada (1837–38)[53] and the Balaiada (1838–41)[53][60] all followed this course, even though in some instances provinces attempted to secede and become independent republics (though ostensibly only so long as Pedro II was a minor).[61] The exception was the Ragamuffin War, which began as yet another dispute between political factions in the province of Rio Grande do Sul[59] but quickly evolved into a separatist rebellion financed by the Argentine dictator Don Manuel Rosas.[62] But even in this case, the majority of the province's population, including the largest and most prosperous cities, remained loyal to the Empire.[63]

Guardianship

Upon leaving the country, Emperor Pedro I selected three people to take charge of his children. The first was his friend José Bonifácio, whom he nominated as guardian,[38][64] a position which was later confirmed by the National Assembly.[38][39] The second was Mariana de Verna, who had occupied the position of aia (supervisor) from the birth of Pedro II.[65] The third person was Rafael,[lower-alpha 3] an afro-Brazilian veteran of the Cisplatine War.[65][66] Rafael was an employee in the Palace of São Cristóvão whom Pedro I deeply trusted and asked to look after his son—a charge which he carried out during the rest of his life.[3][66] São Cristóvão was Pedro II's primary residence from infancy.[67] At the end of 1832 Princess Paula became severely ill (likely with meningitis) and died three weeks later on 16 January 1833.[68] Her loss reinforced the sense of abandonment already felt by Pedro II and his remaining two sisters.[68]

José Bonifácio was dismissed from his position in December 1833.[46] He "brooked no challenge to his omnipotence as guardian. He was quick to take umbrage with those who disputed his prerogatives or challenged his powers, and his dictatorial ways threatened entrenched interests at the court. In particular, he clashed with D. Mariana de Verna Magalhães, who, as first lady of the emperor's bedchamber and supported by numerous relatives, had for several years enjoyed considerable influence in court affairs."[69] His relationship with the liberal-dominated regency had become unsustainable[46] due to his leadership of the restorationist faction which sought to recall Pedro I[46][70] and install him as regent until Pedro II attained majority.[68][71] the National Assembly ratified Manuel Inácio de Andrade, Marquis of Itanhaém as his replacement.[57][72][73]

Itanhaém was chosen for the post because he was considered submissive and easily manipulated.[74] The new guardian proved to be a man of mediocre intelligence,[72] though honest.[74] He was wise enough to provide the young Emperor with an extraordinary education. The guardian had a "great influence on the democratic character and thought of Pedro II."[75] The professors who were already teaching Pedro II and his sisters under José Bonifácio were retained by the new guardian.[76] The exception was Friar Pedro de Santa Mariana who was nominated to occupy the place of aio (supervisor) formerly held by Friar Antonio de Arrábida (who had tutored Pedro I as a child).[77][78] General supervision of Pedro II's education fell to Friar Pedro Mariana, and he took personal charge of his Latin, religion and mathematics studies. He was one of the few people outside his family for whom Pedro II held great affection.[79]

Among the precepts which Itanhaém and Friar Pedro Mariana sought to instill in Pedro II were: that all human beings should be considered as his equals, that he should seek to be impartial and just, that public servants and ministers of state should be carefully watched, that he should not have favourites, and that his concern should always be for the public welfare.[78] Both had as an objective "to make a human, honest, constitutional, pacifist, tolerant, wise and just monarch. That is, a perfect ruler, dedicated integrally to his obligations, above political passions and private interests."[80] Later, in January 1839, Itanhaém called Cândido José de Araújo Viana (later Marquis of Sapucaí) to be instructor of Pedro II's education, and he and the emperor also got on very well.[81]

Education

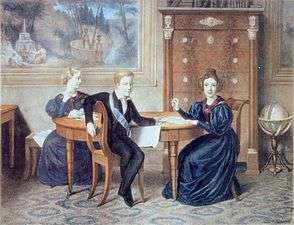

The education of Pedro II began while he was still heir to throne, and he learned to read and write in Portuguese at age five. His first tutors were Mariana de Verna and Friar Antonio de Arrábida.[82] When he became Emperor he already had several professors. Amongst these were Félix Taunay (father of Alfredo d'Escragnolle Taunay) and Luís Alves de Lima e Silva (son of the regent Francisco de Lima e Silva), who taught French and Fencing respectively, and towards both of whom he developed lifelong friendship and admiration.[83][84] Pedro II passed the entire day studying[80] with only two hours reserved for amusements.[45] He would wake up at 6.30 a.m. and begin studies at seven, continuing until 10 p.m., after which he would go to bed.[85] The disciplines were diverse, including everything from languages, history, philosophy, astronomy, physics, geography and music, to hunting, equestrianism and fencing.[45]

Great care was taken to guide him away from his father's example in matters related to education, character and personality.[57][86] He would learn throughout his life to speak and write not only his native Portuguese, but also Latin, French, German, English, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Chinese, Occitan and a Tupi–Guarani language.[87][88][89][90] His passion for reading allowed him to assimilate any information.[91] Pedro II, was not a genius,[22] although he was intelligent and possessed a facility for accumulating knowledge.[92]

As a constitutional monarch, his education was followed closely by the National Assembly, which demanded from Itanhaém progress reports concerning his studies.[75] During this time, Pedro II was kept unaware of events occurring outside the palace, including political matters.[72] News which did intrude upon the emperor and his sisters concerned deaths within their family. In December 1834, they learned of the early and unanticipated death of their father. A few months later their grandfather Francis II, who had shown great interest in his grandchildren, died (June 1835). These losses drew the emperor and his sisters closer together and strengthened their sense of family, despite the absence of their parents.[93]

The Emperor experienced an unhappy and solitary childhood.[3][94] He was considered precocious, docile and obedient,[91][95] but frequently cried and often nothing seemed to please him.[94] He "was not raised in luxury and everything was very simple."[96] As his sisters could not accompany him at other times,[80] he only had permission to meet them after lunch,[95] and even then for only one hour.[57] He had few friends of his age, and the only one he retained into adulthood was Luís Pedreira do Couto Ferraz, future Viscount of Bom Retiro.[65][85][95] However, he was treated tenderly by Mariana de Verna and also by Rafael, who played with him by carrying him on his shoulders[65] and who also allowed Pedro II to hide in his room to escape from studies.[3] For the greater part of his time, he was surrounded by servants who only had permission to speak to him when questioned.[57] The environment in which Pedro II was raised turned him into a shy and needy person[75][97] who saw in "books another world where he could isolate and protect himself."[78][98] Behind the "pomp of the monarchy, of the self-sufficient appearance, there must have lived an unhappy man."[97]

The "Courtier Faction"

From 7 April 1831 Pedro II was Emperor of Brazil,[99] but he would only be able to exercise his constitutional prerogatives upon reaching the age of majority at 18. This would not occur until 2 December 1843.[99][100][101][102][103] The possibility of lowering the age of majority was floated for the first time in 1835 by the conservatives.[100][103][104] On 12 October 1835, the liberal Diogo Antônio Feijó was elected sole regent after the 1834 Additional Act dispensed with the triumvirate regency.[105] He "lacked the vision, flexibility, and resources needed to guide Brazil under conditions which had prevailed since the death of Pedro I and the passage of the Ato Adicional"[106] (Additional Act).

Feijó resigned his position as regent in 1837, and the conservative Pedro de Araújo Lima (later Marquis of Olinda) was elected as his replacement.[107] One of the main goals of Olinda was restore respect for Imperial authority,[108] and thus "traditional ceremonies and practices surrounding the monarch, suspended since Pedro I's abdication, were revived."[108] The "campaign to inculcate deference and respect for the young emperor found ready acceptance throughout Brazil."[109]

Fearful that their adversaries would perpetuate themselves in power, the Liberals had also begun to call for lowering the age of majority.[110] They saw an opportunity, given the emperor's age and inexperience, that "he might be manipulated by whoever brought him to power."[111] The Liberals allied themselves with the former Restorationists, now led by Antônio Carlos and Martim Francisco, brothers of the ex-guardian José Bonifácio de Andrada (who had died in 1838).[111] The bill proposed by the Conservatives to lower the age of majority was defeated in the Senate on 17 May 1840 by a margin of 18 votes to 16.[111][112] In contrast to the Conservatives, Liberals were unscrupulous in ignoring the law to attain their goals and decided to immediately declare Pedro II of age. To accomplish this required the support of the three most powerful people in the Imperial court: Aureliano de Sousa e Oliveira Coutinho, Paulo Barbosa da Silva and Mariana de Verna.[20][84][113]

Aureliano Coutinho, the powerful minister of Justice, had managed to appoint Paulo Barbosa (a friend of his brother Saturnino de Sousa e Oliveira Coutinho)[114] to the position of steward.[84][115] It was Paulo Barbosa who called the Marquis of Itanhaém[74] to become guardian of the princes and Friar Pedro Mariana to be supervisor[116] of Pedro II. He thought both would submit to his interests. Mariana de Verna, former supervisor and surrogate mother of Pedro II and the current first lady-in-waiting, was esteemed by both Aureliano and Paulo Barbosa.[57] Her daughter was married to a nephew of the steward.[117] All "three liked power and influence for its own sake, interpreted any opposition to their dominance in personal terms, and were ruthless in defense of their position at court."[20]

This alliance between "Aureliano, D. Mariana, and Paulo Barbosa, with the marquis of Itanhaém as their adherent, rapidly secured them dominance over the affairs"[118] of the court. It became impossible to advance any proposal or decision without having gained their stamp of approval, while they were chiefly concerned with "their own interests and those of their friends."[118] This trio and their adherents became known as the "Courtier Faction" and the "Joana Club" (named Paulo Barbosa’s country house on the Joana river, where they usually met).[114] Their alliance with the Liberals evolved as a consequence of Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos, one of Olinda's ministers, being eager to remove his sworn enemy Paulo Barbosa and the marquis of Itanhaém from the Imperial Household.[119]

Majority and coronation

Olinda's position was precarious. "He lacked the character and skills to impose his authority, while the attempts he did make to take control were seen as presumptuous, a usurpation of a position belonging to the emperor alone."[120] The "generation of politicians who had come to power in the 1830s, following upon the abdication of Pedro I, had learned from bitter experience the difficulties and dangers of government. By 1840 they had lost all faith in their ability to rule the country on their own. They accepted Pedro II as an authority figure whose presence was indispensable for the country's survival."[121] The Liberals took the dispute over lowering the age of majority directly to the populace, inciting them to place pressure on the politicians.[122] The Brazilian people supported lowering the age of majority[123] and a popular song was heard in the streets: "We want Pedro the Second,/ Although he is not of age;/ The nation excuses the law,/ and long live the majority!"[102][122][124] As emperor, Pedro II "was the living symbol of the unity of the fatherland […] This position gave him, in the eyes of public opinion, a higher authority than that of any regent."[125] The Conservatives weren’t opposed to the Liberal plan, and both (including the regent himself,[126] who would inevitably lose his office) wished to end the regency.[101][103] Olinda asked Pedro II what he thought about the issue of majority, and he simply answered, "I have not thought about that," and continued, "I have already heard about it, but I have not given it any attention."[126]

A crowd of 3,000 people went to the Senate to demand a declaration of majority.[122] The "supporters of an immediate majority gathered at the Senate and passed a motion, signed by 17 senators (out of 49) and by 40 deputies (out of 101), calling on the emperor to take full powers."[127] A delegation of eight, led by Antônio Carlos de Andrada carrying this declaration, proceeded to the Imperial Palace of São Cristóvão to ask if Pedro II would accept or reject the early declaration of his majority.[122][124][126][127] Pedro II asked for the opinion of Itanhaém, Friar Pedro Mariana and Araújo Viana (pawns of the "Courtier Faction"), who convinced him to accept and thus prevent new disorders in the country.[102][127][128] The emperor would say years later that the Liberals had taken advantage of his immaturity and inexperience.[128] He shyly answered "Yes" when asked if he desired the age of majority to be lowered, and "Now" when asked if he would prefer that it come into effect at that moment or if he would wait until his birthday in December.[129][130]

On the following day, 23 July 1840, the National Assembly formally declared the 14-year-old Pedro II of age. A crowd of 8,000 people gathered to witness the act.[99][128] There, in the afternoon, the young emperor took the oath of office.[lower-alpha 4][102][131] For a second time, Pedro II was acclaimed by the gentry, the Armed Forces and the Brazilian people.[128] "There was not, this time, the panic and weeping of 1831. There was only a young and shy boy divided between the fascination of power and the fear of a new world which, unexpectedly, was being opened to him."[132] The "declaration of Pedro II's majority aroused a general euphoria. A feeling of release and renewal united Brazilians. For the first time since the middle of the 1820s the national government at Rio de Janeiro commanded a general acceptance."[133]

Pedro II was acclaimed, crowned and consecrated on 18 July 1841.[134][135] He wore a white robe that had belonged to his grandfather Francis II,[136] an orange pallium made of feathers from the Guianan cock-of-the-rock (a homage to Brazil's birds and indigenous Brazilian chieftains) woven by Tiriyó Indians especially for the emperor[lower-alpha 5] and a green mantle emblazoned with branches of cacao and tobacco, both symbols of the Brazilian empire.[137] After being anointed, he received the Imperial insignia (the Imperial Regalia of Brazil): the Sword (which had belonged to his father[136]), the Scepter (of pure gold[136] with a wyvern on its tip, symbol of the House of Braganza[137]), the Imperial Crown (made especially for the coronation[136] with jewels removed from Pedro I’s crown[138]), the Globe, and the Hand of Justice.[135]

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Upon becoming a widow many years later, on 16 August 1851, Catherine received a room in the City Palace and was supported by Pedro II until her death at age 80 on 19 July 1878. See Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 276.

- ↑ Article 100 of the Brazilian Constitution of 1824 says: "His titles are – Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil –, and is styled – Imperial Majesty". See Rodrigues 1863, p. 71.

- ↑ Little is available concerning Rafael. It is known that he likely was born in Porto Alegre in 1791, and that he died on 16 November 1889 of a heart attack after learning of the emperor's overthrow —Calmon in Calmon 1975, p. 57.

He had been a slave at one time, but was freed somehow and later fought in the Cisplatine War. He traveled along with Pedro II during one of his trips to Europe. —Vainfas in Vainfas 2002, p. 198. - ↑ § "I swear to maintain the Roman, Apostolic, Catholic religion, and the integrity of the Empire, to observe and to enforce the political Constitution of the Brazilian Nation and the other laws of the Empire, and to promote the general good of Brazil as far as this is my responsibility."

- ↑ The material in the pallium would be changed in the 1860s to feathers from the Toucan’s crop. See Schwarcz 1998, p. 78.

Citations

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 424.

- ↑ Bueno 2003, p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vainfas 2002, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 Calmon 1975, p. 4.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Besouchet 1993, p. 39.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 Olivieri 1999, p. 5.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 3.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 46.

- 1 2 Besouchet 1993, p. 40.

- 1 2 Schwarcz 1998, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Barman 1999, p. 1.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, p. 14.

- 1 2 Besouchet 1993, p. 41.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Carvalho 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carvalho 2007, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Barman 1999, p. 49.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 Olivieri 1999, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Calmon 1975, p. 5.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 9.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 10.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 15.

- 1 2 Carvalho 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 16.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 22.

- 1 2 Barman 1999, p. 33.

- ↑ Besouchet 1993, p. 46.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 26.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ Barman 1999, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 Carvalho 2007, p. 21.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carvalho 2007, p. 22.

- 1 2 Calmon 1975, p. 56.

- 1 2 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 18.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 19.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 30.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 Olivieri 1999, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 Carvalho 2007, p. 24.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 21.

- 1 2 Carvalho 2007, p. 36.

- 1 2 Dolhnikoff 2005, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 53.

- ↑ Carvalho 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ Carvalho 2008, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 Carvalho 2007, p. 43.

- ↑ Gonçalves 2009, p. 81.

- ↑ Carvalho 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Gonçalves 2009, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schwarcz 1998, p. 57.

- ↑ Besouchet 1993, p. 61.

- 1 2 Dolhnikoff 2005, p. 206.

- ↑ Souza 2008, p. 326.

- ↑ Janotti 1990, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Holanda 1976, p. 116.

- ↑ Piccolo 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Carvalho 2007, p. 31.

- 1 2 Calmon 1975, p. 57.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Barman 1999, p. 42.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 37.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 31.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Carvalho 2007, p. 25.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Olivieri 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 45.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Carvalho 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, pp. 44–45.

- 1 2 3 Carvalho 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Barman 1999, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, p. 26.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, pp. 39, 46.

- 1 2 3 Carvalho 2007, p. 32.

- 1 2 Vainfas 2002, p. 199.

- ↑ Besouchet 1993, p. 56.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, p. 226.

- ↑ Olivieri 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 428.

- ↑ Besouchet 1993, p. 401.

- 1 2 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 50.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 46.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 53.

- 1 2 Carvalho 2007, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 Besouchet 1993, p. 50.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 60.

- 1 2 Carvalho 2007, p. 33.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 Bueno 2003, p. 194.

- 1 2 Carvalho 2007, p. 37.

- 1 2 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Olivieri 1999, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Schwarcz 1998, p. 67.

- ↑ Olivieri 1999, p. 11.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 61.

- ↑ Barman 1999, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 63.

- 1 2 Barman 1999, p. 64.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 65.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, pp. 37–38.

- 1 2 3 Carvalho 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 71.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 43.

- 1 2 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 93.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 91.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 51.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 275.

- 1 2 Barman 1999, p. 50.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 67.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 68.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 317.

- 1 2 3 4 Carvalho 2007, p. 39.

- ↑ Bueno 2003, pp. 194–195.

- 1 2 Bueno 2003, p. 195.

- ↑ Olivieri 1999, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Schwarcz 1998, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Barman 1999, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Carvalho 2007, p. 40.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 136.

- ↑ Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 70.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 73.

- ↑ Carvalho 2007, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Barman 1999, p. 74.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 73.

- 1 2 Lyra 1977, Vol 1, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Schwarcz 1998, p. 79.

- 1 2 Schwarcz 1998, p. 78.

- ↑ Schwarcz 1998, p. 80.

Bibliography

- Barman, Roderick J. (1999). Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3510-0.

- Besouchet, Lídia (1993). Pedro II e o Século XIX (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. ISBN 978-85-209-0494-7.

- Bueno, Eduardo (2003). Brasil: Uma História (in Portuguese) (1st ed.). São Paulo: Ática. ISBN 978-85-08-08952-9.

- Calmon, Pedro (1975). História de D. Pedro II. 5 v (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio.

- Carvalho, José Murilo de (2007). D. Pedro II: ser ou não ser (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-359-0969-2.

- Carvalho, José Murilo de (2008). Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional (in Portuguese) (Rio de Janeiro: SABIN) 4 (39). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Dolhnikoff, Miriam (2005). Pacto imperial: origens do federalismo no Brasil do século XIX (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Globo. ISBN 978-85-250-4039-8.

- Gonçalves, Andréa Lisly (2009). Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional (in Portuguese) (Rio de Janeiro: SABIN) 4 (45). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de (1976). História Geral da Civilização Brasileira (II) (in Portuguese) 3. DIFEL/Difusão Editorial S.A.

- Janotti, Aldo (1990). O Marquês de Paraná: inícios de uma carreira política num momento crítico da história da nacionalidade (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Lyra, Heitor (1977). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Ascenção (1825–1870) (in Portuguese) 1. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Olivieri, Antonio Carlos (1999). Dom Pedro II, Imperador do Brasil (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Callis. ISBN 978-85-86797-19-4.

- Piccolo, Helga (2008). Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional (in Portuguese) (Rio de Janeiro: SABIN) 3 (37). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Rodrigues, José Carlos (1863). Constituição política do Império do Brasil (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Universal de Laemmert.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (1998). As barbas do Imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-7164-837-1.

- Souza, Adriana Barreto de (2008). Duque de Caxias: o homem por trás do monumento (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. ISBN 978-85-200-0864-5.

- Vainfas, Ronaldo (2002). Dicionário do Brasil Imperial (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva. ISBN 978-85-7302-441-8.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)