Earl Butz

| Earl L. Butz | |

|---|---|

| |

| 18th United States Secretary of Agriculture | |

|

In office December 2, 1971 – October 4, 1976 | |

| President |

Richard M. Nixon Gerald R. Ford |

| Preceded by | Clifford M. Hardin |

| Succeeded by | John A. Knebel |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Earl Lauer Butz July 3, 1909 Albion, Indiana, United States |

| Died |

February 2, 2008 (aged 98) Kensington, Maryland, United States |

| Resting place | Tippecanoe Memory Gardens, West Lafayette, Indiana, United States |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Emma Powell Butz (m. 1937 - 1995, her death) |

| Relations |

Verlo R. Butz Dale E. Butz Ruth E. Butz Buffenbarger Marie M. Butz Howard |

| Children |

William Powell Butz Thomas Earl Butz |

| Parents |

Herman Lee Butz (farmer) Ada Tillie Lower Butz |

| Alma mater | Purdue University |

| Religion | Lutheran |

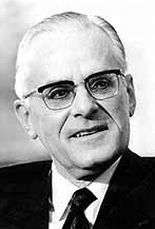

Earl Lauer Butz (July 3, 1909 – February 2, 2008) was a United States government official who served as Secretary of Agriculture under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. His policies favored large-scale corporate farming and an end to New Deal programs, but he is best remembered for a series of verbal gaffes that eventually cost him his job.

Background

Butz was born in Albion, Indiana, and brought up on a dairy farm in Noble County, Indiana. He was the eldest of five children and worked on his parents' 160-acre (65 ha) farm while growing up.[1] He attended a one-room country school through 8th grade and graduated from high school in a class of seven.[2]

Butz was an alumnus of Purdue University, where he was a member of Alpha Gamma Rho fraternity. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in agriculture in 1932, and then a doctorate in agricultural economics in 1937.[3] He was the uncle of American football player Dave Butz.[4][5]

Butz met the former Mary Emma Powell (1911–1995) from North Carolina in 1930, at the National 4-H Camp in Washington, D.C.[3] They were married on December 22, 1937. They had two sons, William Powell and Thomas Earl Butz.[3]

Career

In 1948, Butz became vice president of the American Agricultural Economics Association, and three years later was named to the same post at the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers. In 1954, he was appointed Assistant Secretary of Agriculture by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. That same year he was also named chairman of the United States delegation to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

He left both of the aforementioned posts in 1957, when he became the Dean of Agriculture at his alma mater, Purdue University.[3] In 1968, he was promoted to the positions of Dean of Education and vice president of the university's research foundation.[3] In 1968, he also ran for Governor of Indiana, but came in a distant third at the Republican state convention to eventual winner Edgar Whitcomb and future governor Otis R. Bowen.

Secretary of Agriculture

Butz was Assistant Secretary of Agriculture in Washington, D.C., from 1954 to 1957 under President Dwight Eisenhower. In 1971, President Richard Nixon appointed Butz as Secretary of Agriculture,[3] a position in which he continued to serve after Nixon resigned in 1974 as the result of the Watergate scandal. He was Secretary of Agriculture from 1971 to 1976 under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.[3] In his time heading the USDA, Butz drastically changed federal agricultural policy and reengineered many New Deal era farm support programs.

For example, he abolished a program that paid corn farmers to not plant all their land. (See Henry Wallace's "Ever-Normal Granary".) This program had attempted to prevent a national oversupply of corn and low corn prices. His mantra to farmers was "get big or get out,"[6][7] and he urged farmers to plant commodity crops like corn "from fencerow to fencerow." These policy shifts coincided with the rise of major agribusiness corporations, and the declining financial stability of the small family farm.[8]

Butz took over the Department of Agriculture during the most recent period in American history that food prices climbed high enough to generate political heat. In 1972, the Soviet Union, suffering disastrous harvests, purchased 30 million tons of American grain. Butz had helped to arrange that sale in the hope of giving a boost to crop prices in order to bring restive farmers tempted to vote for George McGovern into the Republican fold.[9]

He was featured in the documentary King Corn, recognized as the person who started the rise of corn production, large commercial farms, and the abundance of corn in American diets. In King Corn, Butz argued that the corn subsidy had dramatically reduced the cost of food for all Americans by improving the efficiency of farming techniques. By artificially increasing demand for food, food production became more efficient and drove down the cost of food for everyone.

Scandals and resignation

At the 1974 World Food Conference in Rome, Butz made fun of Pope Paul VI's opposition to "population control" by quipping, in a mock Italian accent: "He no playa the game, he no maka the rules."[10] A spokesman for Cardinal Cooke of the New York archdiocese demanded an apology, and the White House [10] requested that he apologize.[2] Butz issued a statement saying that he had not "intended to impugn the motives or the integrity of any religious group, ethnic group or religious leader."[10] Through a spokesman, he stated that media outlets had taken this portion of his statement out of their original context, which was that of retelling a joke.[11]

Butz resigned his cabinet post on October 4, 1976, after a second gaffe. News outlets revealed a racist remark he made in front of entertainers Pat Boone and Sonny Bono and former White House counsel John Dean while aboard a commercial flight to California following the 1976 Republican National Convention. The October 18, 1976 issue of Time reported the comment while obscuring its vulgarity:[12]

- Butz started by telling a dirty joke involving intercourse between a dog and a skunk. When the conversation turned to politics, Boone, a right-wing Republican, asked Butz why the party of Lincoln was not able to attract more blacks. The Secretary responded with a line so obscene and insulting to blacks that it forced him out of the Cabinet last week and jolted the whole Ford campaign. Butz said: "I'll tell you what the coloreds want. It's three things: first, a tight pussy; second, loose shoes; and third, a warm place to shit."

- After some indecision, Dean used the line in Rolling Stone, attributing it to an unnamed Cabinet officer. But New Times magazine enterprisingly sleuthed out Butz's identity by checking the itineraries of all Cabinet members.

The reference in Time was to John Dean's article published in Rolling Stone issue #223.[13][14]

In any case, according to The Washington Post, anyone familiar with Beltway politics could "have not the tiniest doubt in [their] mind[s] as to which cabinet officer" uttered it.[2]

While the Associated Press sent the uncensored quotation over the wire, the Columbia Journalism Review claims that only two newspapers — the Toledo Blade (Toledo, Ohio) and the Madison Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin) — published the remark unchanged. In fact, however, the Michigan Daily, the newspaper of the University of Michigan, also published the entire, uncensored, quote. Others bowdlerized the quote, in some cases replacing the female genital reference with "a tight [obscenity]" and the scatological reference with "a warm place to [vulgarism]" or "warm toilet seats". The Lubbock Avalanche-Journal said the original statement was available in the newspaper office; more than 200 stopped by to read it. The San Diego Evening Tribune offered to mail a copy of the whole quotation to anyone who requested it; more than 3,000 readers did.[15]

According to Timothy Noah of Slate, this incident was "epochal" because before this, politicians assumed such offensive remarks could be uttered safely in private; after Butz's resignation, politicians "could no longer assume your fellow whites would protect you for telling a joke insulting to blacks, and you could no longer assume your fellow blacks would protect you for telling a joke insulting to Jews."[16]

The infamous quote was the origin of the movie title Loose Shoes which includes a skit, looking like Cab Calloway band "Darktown After Dark".[17]

Retirement and death

| Wikinews has related news: American government official Earl Butz dies at age 98 |

Butz returned to West Lafayette, Indiana, and was named dean emeritus of Purdue University's School of Agriculture.[18][19][20][21]

On May 22, 1981, Butz pleaded guilty to federal tax evasion charges for having underreported income he had earned in 1978. On June 19 he was sentenced to five years in prison; however, all but 30 days of the term were suspended. He was also fined $10,000 and ordered to pay $61,183 in civil penalties.[22]

Butz continued to serve on corporate boards and speak on agricultural policy. At an international conference in Geneva, Switzerland (sponsored by the Agri-Energy Roundtable (AER) on May 23, 1983, Butz warned his audience (concerning ethanol production and subsidies), "Those who ride the Tiger may find dismounting difficult". A number of those present had represented their countries during the famous 1974 World Food Security Summit (Rome) where Butz had led the US delegation.

Butz died in his sleep on February 2, 2008, in Kensington, Maryland.[23] He is buried at the Tippecanoe Memory Gardens in West Lafayette, Indiana.

At his death, Butz was the oldest living former Cabinet member from any administration.[24][25]

References

- ↑ Robbins, William (4 October 1976). "Butz Delights in Conflict". Lakeland Ledger via New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Children of the Corn Syrup," Shea Dean, The Believer, October 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Forbes, Beth (2 February 2008). "Former Purdue Agriculture Dean Earl Butz dead at 98". Purdue News. Randy Woodson, Wally Tyner; sources. Purdue University. Retrieved 27 July 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Dave Butz defends uncle". Lakeland Ledger. 7 October 1976. p. 1B. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ "Uncle Dave ill-treated, Redskin says". The Free Lance-Star. 7 October 1976. p. 6. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ Scholar, Heather H. (23 October 1973). "Federal Farm Policies Hit". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ Michael Carlson (7 February 2008). "Obituary: Earl Butz | World news". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ Imhoff, Daniel. "Family Farms to Mega-Farms". Foodfight, The Citizen's Guide To A Food And Farm Bill. Watershed Media. ISBN 0-9709500-2-0.

The Farm Bill is actually succeeding at one of its decades-old policy objectives:driving small- to medium-scale commodity farmers off the land.

- ↑ Pollan, Michael (2006). The Omnivore's Dilemma. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303858-0.

- 1 2 3 "Quiet Please," TIME Magazine, December 9, 1974

- ↑ "Butz: 'I'ma Sorry I Speaka Dat Way'." Indianapolis News 1974-11-29: 1.

- ↑ "Exit Earl, Not Laughing," Time, October 18, 1976.

- ↑ Dean, John; Steadman, Ralph (7 October 1976). "Rituals of the Herd". Rolling Stone (Jann Wenner) (223). ISSN 0035-791X External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ "Rolling Stone's Biggest Scoops, Exposés and Controversies, #7: Earl Butz Mouths Off". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. ISSN 0035-791X. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

[John Dean] recounted a joke Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz told him: "I'll tell you what coloreds want," Butz said. "It's three things: first, a tight pussy; second, loose shoes; and third, a warm place to shit. That's all!" Butz resigned soon after.

External link in|website=(help) - ↑ Levitas, Daniel (2002). The terrorist next door : the militia movement and the radical right (1st ed.). New York: Dunne u.a. p. 459. ISBN 0312291051.

- ↑ Timothy Noah, "Earl Butz, History's Victim: How the gears of racial progress tore up Nixon's Agriculture secretary", Slate.com, Feb. 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Dark Town After Dark, Loose Shoes". YouTube. 2006-09-26. Retrieved 2014-09-29.

- ↑ "Earl Butz". People in the News. The Times-News, Hendersonville, NC. 22 August 1981. p. 2. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ "Butz donates $1 million to Purdue ag econ department". Purdue.edu. 1967-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ "Hard work, insight enabled Butz to become agricultural leader". Kpcnews.net. 1909-07-03. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ "Gerald R. Ford Administration Alumni". Gerald Ford Presidential Foundation. Gerald Ford Foundation. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Butz Released 5 Days Early", Associated Press, July 25, 1981

- ↑ Goldstein, Richard (February 4, 2008). "Earl Butz dies at 98". Rutland Herald via New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ O'Keefe, Ed (2009-04-03). "Federal Eye - Spotted: Oldest Living Ex-Cabinet Secretary Releases Book". Voices.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ Gerald R. Ford Administration Alumni | The Gerald Ford Presidential Foundation

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Earl Butz |

- "Meeting King Corn: Earl Butz was a product of his time" 2/19/2008

- "The Butz Stops Here: A reflection on the lasting legacy of 1970s USDA Secretary Earl Butz" 2/7/2008

- Agri-Pulse article "Memories of Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz" 2/10/2008

- High Plains/Midwest Ag Journal article: "Memories of Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz" 2/14/2008

- Farm Futures article: "A Special Tribute to Earl Butz" 2/4/2008

- Burial place of Earl Butz at Find A Grave

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Clifford M. Hardin |

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Served under: Richard M. Nixon, Gerald R. Ford December 2, 1971 – October 4, 1976 |

Succeeded by John A. Knebel |

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|