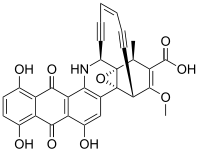

Dynemicin A

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(1S,4R,4aR,14S,14aS,18Z)-6,8,11-trihydroxy-3-methoxy-1-methyl-7,12-dioxo-1,4,7,12,13,14-hexahydro-4a,14a-epoxy-4,14-hex[3]ene[1,5]diynonaphtho[2,3-c]phenanthridine-2-carboxylic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 124412-57-3 | |

| ChemSpider | 8205706 |

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image |

| PubChem | 10030135 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C30H19NO9 | |

| Molar mass | 537.473 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Dynemicin A is an anti-cancer enediyne drug. It displays properties which illustrate promise for innovative cancer treatments, but still requires further research.

History and background

Dynemicin A was first isolated from the soil in the Gujarat State of India. It was discovered to be the natural product of the indigenous bacteria Micromonospora chersina. The natural product displays a bright purple color due to the anthraquinone chromophore structure within Dynemicin A. Initially this compound was isolated for its aesthetic properties as a dye, until further research demonstrated its anti-cancer properties. Shortly after the compound’s discovery, the Bristol-Myers Pharmaceutical Company first elucidated the structure in Japan. The structure of dynemicin A was determined from X-ray diffraction studies of triacetyldynemicin A; a closely related compound.

Synthesis

The first reported synthesis of dynemicin was accomplished by Myers and coworkers.[1]

Biosynthesis

Dynemicin A is an antitumor natural product isolated from Micromonospora chersina which causes DNA strand cleavage. Iwasaki et al. first studied the biosynthetic pathway of Dynemicin A by 13C NMR labeling experiments.[2] Dynemicin A is thought to be biosynthesized separately from two different heptaketide chains originated from seven head-to-tail coupled acetate units, which is then connected to form Dynemicin A. Initially, precursors such as 3 and 4 were proposed to derive from the oleate/crepenynate pathway, as initially put forth for NSC Chrom A biosynthesis.[3] However, recent work by Thorson and coworkers revealed the biosynthesis of the dynemicin enediyne core to be catalyzed by an enediyne polyketide synthase (PKSE) similar to that employed in calicheamicin biosynthesis.[4][5]

Mechanism of action

Dynemicin A is specific for B-DNA, and functions by intercalating into the minor groove of the double helix. For intercalation to occur the separation between strands which is usually 3-4 angstroms needs to be widened to 7-8 angstroms to allow enough space for the ligand to bind. Given this the DNA must be strained to accommodate the Dynemicin A resulting in an induced fit-like process. Once intercalated within the DNA the epoxide is activated in one of two ways. First, if NADPH or a thiol reduces the molecule the Bergman re-cyclization of the enediyne proceeds. Second if a nucleophilic mechanism is utilized then the retro-Bergman re-cyclization of the enediyne is used. The final products of these two mechanisms are outlined below. When the re-cyclization occurs, the conformational changes and chemical reactions taking place result in a non-reversible double stranded cleavage of the DNA, leading to in cell death. This mechanism is extremely cytotoxic because prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells alike do not possess a mechanism to repair a double stranded cleavage of their DNA. During in vitro studies the molecule showed an increased affinity for a specific 10 base pair sequence (CTACTACTTG). In vivo studies have yet to confirm this phenomenon. Professor Martin Semmelhack from Princeton University was the first person to propose the NADPH reduction pathway.

Pharmacological properties

The pharmacological properties of this drug have not yet been fully explored but currently suggest that it may be a more potent anti-cancer agent than other chemotherapeutic drugs. The bacterium is believed to use dynemicin A as an antibacterial agent to help it survive in its niche in the environment. Dynemicin A, as a drug, specifically targets B-DNA and is most effective in rapidly dividing cells. The broad spectrum of the drug prevents current use because it creates unwanted damage in normal healthy tissues. In vivo studies in mice and rats suggest that the treatment is most effective in leukemia, breast and lung cancers. Synthetic alternatives which are more specific to cancer cells and leave healthy tissues unharmed are being researched. Other animal models are available but have proven ineffective and therefore there are currently no human trials underway. The enediyne property of this drug relates to another antibiotic known as neocarzinostatin which is approved for clinical use. As with dynemicin A, neocarzinostatin also interacts with DNA.

References

- ↑ Myers, AG; Fraley, ME; Tom, NJ; Cohen, SB; Madar, DJ (January 1995). "Synthesis of (+)-dynemicin A and analogs of wide structural variability: establishment of the absolute configuration of natural dynemicin A.". Chemistry & Biology 2 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1016/1074-5521(95)90078-0. PMID 9383401.

- ↑ Tokiwa, Y.; Miyoshi-Saitoh, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Sunaga, R.; Konishi, M.; Oki, T.; Iwasaki, S (1992). "Biosynthesis of dynemicin A, a 3-ene-1,5-diyne antitumor antibiotic". J. Am. Chem. Soc 114 (11): 4107–4110. doi:10.1021/ja00037a011.

- ↑ Hensens, O. D.; Giner, J.; Goldberk, I. H (1989). "Biosynthesis of NCS Chrom A, the chromophore of the antitumor antibiotic neocarzinostatin". J. Am. Chem. Soc 111: 3295–3299. doi:10.1021/ja00191a028.

- ↑ Liu, W; Ahlert, J; Gao, Q; Wendt-Pienkowski, E; Shen, B; Thorson, JS (14 October 2003). "Rapid PCR amplification of minimal enediyne polyketide synthase cassettes leads to a predictive familial classification model.". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (21): 11959–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.2034291100. PMID 14528002.

- ↑ Gao, Q; Thorson, JS (May 2008). "The biosynthetic genes encoding for the production of the dynemicin enediyne core in Micromonospora chersina ATCC53710.". FEMS microbiology letters 282 (1): 105–14. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01112.x. PMID 18328078.

- ElSohly, Adel. "Dynemicin A: Molecule in Review." Columbia University. 12 June 2009.

- Liew, C. W.; Scharff, A.; Kotaka, M.; Kong, R.; Sun, H.; Qureshi, I.; Bricogne, G.; Liang, Z.; Lescar, J. (2010). "Induced-fit upon Ligand Binding Revealed by Crystal Structures of the Hot-dog Fold Thioesterase in Dynemicin Biosynthesis". J. Mol. Biol. 404: 291–306. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.041.

- Nicolaou, K. C., S. A. Snyder, A. G. Meyers, and S. J. Danishefsky. "Dynemicin A." Classics in Total Synthesis II: More Targets, Strategies, Methods. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2003. 75-107.

- Schulz-Aellen, Marie-Françoise. "Cancer Drugs." Aging and Human Longevity. Boston: Birkhäuser, 1997. 203-04

- Silverman, Richard B. "Dynemicin A." The Organic Chemistry of Drug Design and Drug Action. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic, 2004. 381-85

- Tuttle, Tell; Kraka, Elfi; Cremer, Dieter (2005). "Docking, Triggering, and Biological Activity of Dynemicin A in DNA: A Computational Study". Journal of the American Chemical Society 127 (26): 9469–484. doi:10.1021/ja046251f.

- Tuttle, Tell; Kraka, Elfi; Theil, Walter; Cremer, Dieter (2007). "A QM/MM Study of the Bergman Reaction of Dynemicin A in the Minor Groove of DNA". J Phys Chem 111: 8321–328. doi:10.1021/jp072373t.

External links

- http://www.columbia.edu/cu/chemistry/groups/synth-lit/MIR2009/2009_06_12-AElsohly-Dynemycin.pdf

- http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/pubmedArticle.do?structureId=2XFL#

- http://books.google.com/books?id=PE587tLs3w0C&pg=PA76&lpg=PA76&dq=Bristol-Myers+structure+dynemicin+a&source=bl&ots=X-l9kgIwfu&sig=H6RCeET9W75_KSupYJhxx3gYRsc&hl=en&ei=_CG6TdWJL8rz0gHYusRt&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CDgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Bristol-Myers%20structure%20dynemicin%20a&f=false

- http://books.google.com/books?id=7l6IOF2t3vIC&pg=PA203&lpg=PA203&dq=where+does+dynemicin+a+come+from&source=bl&ots=fcczlI2BvW&sig=mUWUqTwG283RgGvAxUARhqMJNcw&hl=en&ei=GKe0TabeNouO0QGSwPSfCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=dynemycin&f=false

- http://smu.edu/catco/pdf/jacs_127_9469.pdf

- http://smu.edu/catco/pdf/JPC-B_111_8321.pdf

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/media/81/Examples-of-anthraquinone-pigments

- http://www.chem.strath.ac.uk/people/academic/tell_tuttle/research/qmmm