Duchy of Saxony

| Duchy of Saxony | |||||

| Hartogdom Sassen - Herzogtum Sachsen | |||||

| Stem duchy of the Carolingian Empire (843–911) and of East Francia (911–962) State of the Holy Roman Empire (from 962) | |||||

| |||||

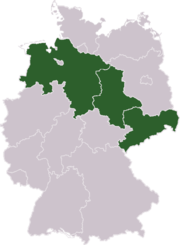

Saxonia about 1000, 19th century map | |||||

| Capital | Not specified | ||||

| Government | Principality | ||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| • | Formation by Charlemagne | 804 | |||

| • | Welfs ascendancy | 1137 | |||

| • | Expanded by conquest | 1142 | |||

| • | Welfs deposed, Ascanians enfeoffed with severely belittled duchy | 1180 | |||

| • | John I and Albert II co-rulers; - Competences divided | 1260 1269, 1272 and 1282 | |||

| • | Definite partition into Saxe-Lauenburg and Saxe-Wittenberg | 1296 | |||

| • | Wittenbergs extinct; reunification failed | 1422 | |||

| * | |||||

The Duchy of Saxony (Low German: Hartogdom Sassen, German: Herzogtum Sachsen) was originally the area settled by the Saxons in the late Early Middle Ages, when they were subdued by Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars from 772 and incorporated into the Carolingian Empire (Francia) by 804. Upon the 843 Treaty of Verdun, Saxony was one of the five German stem duchies of East Francia; Duke Henry the Fowler was elected German king in 919.

Upon the deposition of the Welf duke Henry the Lion in 1180, the ducal title fell to the House of Ascania, while numerous territories split from Saxony. In 1296 the remaining lands were divided into the duchies of Saxe-Wittenberg and Saxe-Lauenburg.

Geography

The Saxon stem duchy covered the greater part of present-day Northern Germany, including the modern German states (Länder) of Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt up to the Elbe and Saale rivers in the east, the city-states of Bremen and Hamburg, as well as the Westphalian part of North Rhine-Westphalia and the Holstein region (Nordalbingia) of Schleswig-Holstein. In the late 12th century, Duke Henry the Lion also occupied the adjacent area of Mecklenburg (the former Billung March).

The Saxons were one of the most robust groups in the late tribal culture of the times, and eventually bequeathed their tribe's name to a variety of more and more modern geo-political territories from Old Saxony (Altsachsen) near the mouth of the Elbe up the river via the Prussian Province of Saxony (in present-day Saxony-Anhalt) to Upper Saxony, the Electorate and Kingdom of Saxony from 1806 corresponding with the German Free State of Saxony, which bears the name today though it was not part of the medieval duchy (see map on the right).

History

Older stem duchy

According to the Res gestae saxonicae by 10th century chronicler Widukind of Corvey, the Saxons had arrived from Britannia at the coast of Land Hadeln in the Elbe-Weser Triangle, called by the Merovingian rulers of Francia to support the conquest of Thuringian kingdom. More probably, Saxon tribes from Land Hadeln under the leadership of legendary Hengist and Horsa in the late days of the Roman Empire had invaded Britannia. (see Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain).

The Royal Frankish Annals mention a 743 Frankish campaign led by the Carolingian Mayor of the Palace Carloman against the Saxons, followed by a second expedition together with his brother Pepin the Short the next year. In 747 their rebellious brother Grifo allied with Saxon tribes and temporarily conquered the stem duchy of Bavaria. Pepin, Frankish king from 750, again invaded Saxony and subdued several Westphalian tribes until 758.

In 772 Pepin's son Charlemagne started the final conquest of the Saxon lands. Though his ongoing campaigns were successful, he had to deal with the fragmentation of the Saxon territories in Westphalian, Eastphalian and Angrian tribes, demanding the conclusion of specific peace agreements with single tribes, which soon were to be broken by other clans. The Saxons devastated the Frankish stronghold at Eresburg; their leader (Herzog) Widukind refused to appear at the 777 Imperial Diet at Paderborn, retired to Nordalbingia and afterwards led several uprisings against the occupants, avenged by Charlemagne at the (alleged) Massacre of Verden in 782. Widukind finally had to pledge allegiance in 785, having himself baptised and becoming a Frankish count. Saxon uprisings continued until 804, when the whole stem duchy had been incorporated into the Carolingian Empire.

Afterwards, Saxony was ruled by Carolingian officials, e.g. Wala of Corbie (d. 836), a grandson of Charles Martel and cousin of the emperor, who in 811 fixed the Treaty of Heiligen with King Hemming of Denmark, defining the northern border of the Empire along the Eider River. Among the installed dukes were already nobles of Saxon descent, like Wala's successor Count Ekbert, husband of Saint Ida of Herzfeld, a close relative of Charlemagne.

Younger stem duchy

Ida of Herzfeld may have been an ancestor of the Saxon count Liudolf (d. 866), who married Oda of Billung and ruled over a large territory along the Leine river in Eastphalia, where he and Bishop Altfrid of Hildesheim founded Gandersheim Abbey in 852. Liudolf became the progenitor of the Saxon ducal, royal and imperial Ottonian dynasty; nevertheless his descendance, especially his affiliation with late Duke Widukind, has not been conclusively established.

Subdued only a few decades earlier, the Saxons rose to one of the leading tribes in East Francia; it is however uncertain, if the Ottonians already held the ducal title in the 9th century. Liudolf's elder son Bruno (Brun), progenitor of the Brunswick cadet branch of the Brunonen, was killed in a battle with invading Vikings under Godfrid in 880. He was succeeded by his younger brother Otto the Illustrious (d. 912), mentioned as dux in the contemporary annals of Hersfeld Abbey, which however seems to have been denied by the Frankish rulers. His position was strong enough to wed Hedwiga of Babenberg, daughter of mighty Duke Henry of Franconia, princeps militiae of King Charles the Fat. As all of Hedwiga's brothers were killed in the Franconian Babenberg feud with the rivalling Conradines, Otto was able to adopt the strong position of his father-in-law and to evolve the united Saxon duchy under his rule.

In 911 the East Frankish Carolingian dynasty became extinct with the death of King Louis the Child, whereafter the dukes of Saxony, Swabia and Bavaria met at Forchheim to elect the Conradine duke Conrad I of Franconia king. One year later, Otto's son Henry the Fowler succeeded his father as Duke of Saxony. According to the medieval chronicler Widukind of Corvey, King Conrad designated Henry his heir, thereby denying the succession of his own brother Eberhard of Franconia, and in 919 the Saxon duke was elected King of East Francia by the assembled Saxon and Franconian princes at Fritzlar. Henry was able to integrate the Swabian, Bavarian and Lotharingian duchies into the imperial federation, vital to handle the continuous attacks by Hungarian forces, whereby the Saxon troops about 928/929 occupied large territories in the east settled by Polabian Slavs. Henry's eastern campaigns to Brandenburg and Meissen, the establishment of Saxon marches as well as the surrender of Duke Wenceslaus of Bohemia marked the beginning of the German eastward expansion (Ostsiedlung).

House of Billung

Upon Henry's death in 936 at Memleben, his son Otto I succeeded him. According to Widukind, he was crowned king at Aachen Cathedral, with the other German dukes Gilbert of Lorraine, Eberhard of Franconia, Arnulf of Bavaria and Herman of Swabia paying homage to him. Like his father, he chose not to relinquish the Saxon ducal dignity, and instead appointed Hermann Billung a princeps militiae or margrave ("Markgraf") of Saxony in 938, mainly in order to subdue the Slavic Lutici tribes in what was to become the Billung March beyond the Elbe River. He thereby disregarded the claims of Herman's elder brother Wichmann, who in turn joined the failed revolt by Otto's half-brother Thankmar. In 953 and again in 961 King Otto elevated Hermann Billung to a viceduke in Saxony, though he reserved the dux title for himself.

- 973: Otto I dies in Memleben; Otto II becomes Emperor. Hermann Billung dies in Quedlinburg; Bernhard I Billung becomes duke of Saxony.

- 983: Danish uprising in Hedeby. Slavonian uprising in Northalbingia. Otto III becomes Emperor.

- 1002: The death of Otto III marks the end of the Saxon emperors.

- 1011: Duke Bernhard I Billung dies; his son Bernhard II becomes duke.

- 1042: Ordulf Billung, son of Bernhard II, marries Wulfhild, the half-sister of King Magnus of Denmark and Norway. Danes and Saxons fight against the Wends.

- 1059: Ordulf Billung becomes Duke after the death of his father.

- 1072: Magnus Billung becomes Duke.

- 1106: Duke Magnus dies without heir, ending the Billung dynasty. The Billung territory becomes part of the Welf and Ascanian countries. Lothar of Supplinburg becomes Duke of Saxony.

- 1112: Otto of Ballenstedt created Duke by Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor.

- 1115: Victory of Lothar of Supplinburg in the battle of Welfesholz over King Henry V.

- 1125: Lothar of Supplinburg elected as German King and crowned Emperor, as Lothar II.

- 1137 Death of Lothar. The Welf Henry X the Proud, Duke of Bavaria since 1126, had been appointed Lothar's successor (who died without a male heir) as Duke of Saxony. However, as he was not officially invested and it would make him far too powerful, his claim is not recognized by his rivals.

- 1138: Henry X loses the election for King of the Germans against Conrad of Hohenstaufen. Insisting to hold both duchies, Bavaria and Saxonia, a claim Conrad opposes, Henry refuses an oath of allegiance and is consequently stripped of all his titles. The Duchy of Saxony is granted to the Ascanian Albert the Bear.

- 1139: Due to his marriage to Lothar's only daughter Gertrude of Supplingenburg, Henry still holds substantial lands within the Duchy of Saxony. Henry fiercely resists Albert's attempts to take possession of Saxony. Preparing an attack on the Duchy of Bavaria, Henry X dies unexpectedly.

- 1141: Albert the Bear renounces the Duchy of Saxony and the title (as well as the Duchy of Bavaria) is granted to Henry X adolescent son Henry the Lion.

Henry the Lion

In 1142 King Conrad III of Germany granted the ducal title to the Welf scion Henry the Lion (as Duke Henry III). Henry gradually extended his rule over northeastern Germany, leading crusades against the pagan Wends. During his reign Henry massively supported to the development of the cities in his dominion, such as Brunswick, Lüneburg and Lübeck, a policy ultimately contributing to the movement of the House of Welf from its homelands in southern Germany to the north.

In 1152 Henry supported his cousin Frederick III of Swabia to be elected King of Germany (as Frederick I Barbarossa), probably being promised to regain the Duchy of Bavaria in exchange. Henry's dominion now covered more than two thirds of Germany from the Alps to the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, making him one of the mightiest ruler in central Europe, and thus also a potential threat for other German princes and even Barbarossa.

To expand his rule, Henry continued to claim titles of lesser families, who left no legitimate heir. This policy caused unrest among many Saxon nobles and other German princes, first and foremeost his father's old enemy, Albrecht the Bear. During Barbarossa's fourth Italian campaign in 1166, a league of German Nobles declared war on Henry. The war continued until 1170, despite several attempts of the Emperor to mediate. Ultimately, Henry's position remained unchallenged, due to Barbarossa's favourable rule.

In 1168, Henry married Matilda Plantagenêt, the daughter of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine and sister of Richard Lionheart.

The following years led to an estrangement between Barbarossa and Henry. Henry ceased to support the Emperor's Italy campaigns, which were all proven unsuccessful, as massively as he used to, and instead focused on his own possessions. In 1175 Barbarossa again asked for support against the Lombard League, which Henry is said to have refused bluntly, even though Barbarossa kneeled before him. Records of this event were not written until several years later, and sources are contradictory, depending on whom the author favoured. Nevertheless, lacking the support of the Saxons the following Battle of Legnano was a complete failure for the Emperor.

When the majority of the realm's princes had returned from Italy, Henry's refusal was instantly exploited to weaken his position. Views differ, whether Barbarossa initiated Henry's downfall or if it was orchestrated by the princes first and foremost.[1]

Between 1175 and 1181 Henry was charged with several accusations, such as violating the honour of the realm (honor imperii), breach of the peace, and treason. Because by following the summons to the Hoftag, Henry would've acknowledge the charges as rightful, he refused all of them. In 1181 he was ultimately stripped of his titles. Unwilling to give up without a fight, Henry already had dealt the first blow in 1180 against the city of Goslar, which he had coveted for several years already. During the following war, Henry's domestic policy and the treatment of his vassals proved fatal, and his power quickly crumbled. In 1182 Henry the Lion ultimately went into Exile, joining the court of his father-in-law, Henry II of England. Following the death of his wife and the Emperor participating in the Third Crusade Henry returned to Brunswick in 1189 and briefly tried to regain the lost lands. After several setbacks Henry made peace with Barbarossa's son and heir, King Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor.

The ancient stem duchy of Saxony was partitioned in some dozens of territories of imperial immediacy by Barbarossa, and ceased to exist. The western part was split in several minor counties and bishoprics, and the newly formed Duchy of Westphalia. In the east, the Ascanians, the Welf's old rivals, finally gained a, severely belittled, Duchy of Saxony, occupying only the easternmost, comparably small territories along the river Elbe around Lauenburg upon Elbe and around Wittenberg upon Elbe. Limiting the lands the Ascanians gained along with the ducal title to these eastern territories caused the migration of the name Saxony from north-western Germany to the location of the modern Free State of Saxony.

The deposed ducal House of Welf could maintain its allodial possessions, which did not remain part of the Duchy of Saxony after the enfeoffment of the Ascanians. The Welf possessions were elevated to the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also Brunswick and Lunenburg) in 1235. This duchy continued to use the old Saxon coat-of-arms showing the Saxon Steed in argent on gules, while the Ascanians adopted for the younger Duchy of Saxony their family colours, a barry of ten, in sable and or, covered by a crancelin of rhombs bendwise in vert, symbolising the Saxon dukedom.

House of Ascania

In 1269, 1272 and 1282 the co-ruling brothers John I and Albert II gradually divided their governing competences within the then three territorially unconnected Saxon areas (Hadeln, Lauenburg and Wittenberg), thus preparing a partition.

After John I had resigned in 1282 in favour of his three minor sons Eric I, John II and Albert III, followed by his death three years later, the three brothers and their uncle Albert II continued the joint rule in Saxony.

In 1288 Albert II applied at King Rudolph I for the enfeoffment of his son and heir Duke Rudolph I with the Palatinate of Saxony, which ensued a long lasting dispute with the eager clan of the House of Wettin. When the County of Brehna was reverted to the Empire after the extinction of its comital family the king enfeoffed Duke Rudolph. In 1290 Albert II gained the County of Brehna and in 1295 the County of Gommern for Saxony. King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia succeeded in bringing Albert II in favour of electing Adolf of Germany as new emperor: Albert II signed an elector pact on 29 November 1291 that he would vote the same as Wenceslaus. On 27 April 1292 Albert II, with his nephews still minor, wielded the Saxon electoral vote, electing Adolf of Germany.

The last document, mentioning the joint government of Albert II with his nephews as Saxon fellow dukes dates back to 1295.[2] The definite partitioning of the Duchy of Saxony into Saxe-Lauenburg (German: Herzogtum Sachsen-Lauenburg), jointly ruled by the brothers Albert III, Eric I and John II and Saxe-Wittenberg (German: Herzogtum Sachsen-Wittenberg), ruled by Albert II took place before 20 September 1296. The Vierlande, Sadelbande (Land of Lauenburg), the Land of Ratzeburg, the Land of Darzing (today's Amt Neuhaus), and the Land of Hadeln are mentioned as the separate territory of the brothers.[3] Albert II received Saxe-Wittenberg around the eponymous city and Belzig. Albert II thus became the founder of the Ascanian line of Saxe-Wittenberg.

Members of the Welf cadet branch House of Hanover later became prince-electors of Brunswick-Lüneburg (as of 1692/1708), kings of Great Britain, Ireland (both 1714), the United Kingdom (1801) and Hanover (1814).

Territories seceded from Saxony after 1180

A number of seceded territories even gained imperial immediacy, while others only changed their liege lord on the occasion. The following list includes states that existed in the territory of the former stem duchy in addition to the two legal successors of the stem duchy, the Ascanian Duchy of Saxony formed in 1296 centered around Wittenberg and Lauenburg, as well as the Duchy of Westphalia, held by the Archbishops of Cologne, that already split off in 1180.

Westphalia

- County of Bentheim

- County of Mark

- Prince-Bishopric of Münster

- Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück

- County of Ravensberg

- County of Tecklenburg

Angria

- Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen

- Abbacy of Corvey

- County of Delmenhorst

- County of Diepholz

- County of Everstein

- County of Hoya

- Lordship of Lippe, an allodial possession within the Duchy of Saxony until 1180, gaining disputed imperial immediacy

- Prince-Bishopric of Minden

- County of Oldenburg

- Prince-Bishopric of Paderborn

- Prince-Bishopric of Verden

- County of Waldeck

Eastphalia

- County of Blankenburg, until 1180 a Saxon fief, then a fief of the Prince-Bishopric of Halberstadt

- County of Brunswick, later the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1235), the Welf allodial possessions

- Abbacy of Gandersheim

- Prince-Bishopric of Halberstadt

- Prince-Bishopric of Hildesheim

- County of Hohenstein, seated in Hohenstein

- Prince-Archbishopric of Magdeburg

- County of Mansfeld

- Abbacy of Quedlinburg

- County of Wernigerode

Nordalbingia

- County of Holstein

- Prince-Bishopric of Lübeck

- Prince-Bishopric of Ratzeburg

- Prince-Bishopric of Schwerin

See also

Notes

- ↑ Knut Görich: Jäger des Löwen oder Getriebener der Fürsten? Friedrich Barbarossa und die Entmachtung Heinrichs des Löwen. In: Werner Hechberger, Florian Schuller (Hrsg.), Staufer & Welfen. Zwei rivalisierende Dynastien im Hochmittelalter. Regensburg 2009, S. 99–117.

- ↑ Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373-389, here p. 375. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- ↑ Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373-389, here p. 375. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

|