Edward Cutbush

| Edward Cutbush | |

|---|---|

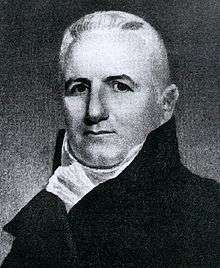

Dr. Edward Cutbush - c. 1835 | |

| Born |

1772 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

July 23, 1843 (aged 71) Geneva, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Pennsylvania 1794 |

|

Medical career | |

| Profession | Physician and Educator |

| Field | United States Navy |

Edward Cutbush (1772 – July 23, 1843) was born in Philadelphia. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1794, where he was resident physician of the Pennsylvania Hospital from 1790 to 1794.[1] Cutbush was surgeon general of the Pennsylvania militia during the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion.[2]

He was an officer and a surgeon in the United States Navy and was commissioned into office in 1799.[1] Cutbush has been called the father of American naval medicine.[3] He resigned from the Navy in 1829, after 30 years of service. During 1826, he was a Professor of Chemistry at Columbian College in the District of Columbia. In 1834, he relocated to Geneva, New York, where he founded Geneva Medical College. During his tenure there, he served as the first dean and Professor of Chemistry.[4]

Biography

Cutbush was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1772. He was the son of Edward Cutbush (1745–1790)[5] and Anne Marriat (d.1789)[5] who married on September 3, 1770.[6] His father, a British immigrant, was a stonecutter or carver.[7] Philadelphian, William Rush (1756–1833), a famous woodworking artist and carver of ship models, was an apprentice of the senior Cutbush. Rush began carving ship figureheads as early as 1790 and gained much notoriety for his distinguished artwork.[8]

Education

Cutbush was a student at Philadelphia College by age 12.[3] He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1794, where he was resident physician of the Pennsylvania Hospital from 1790 to 1794.[1] During his time there, he worked under Dr. William Shippen. While still a student, he was honored by the city of Philadelphia for his services during the 1793 yellow fever epidemic.[3]

Personal life

Edward Cutbush was the eldest of four children. His siblings were Ann Cutbush (1792–1798), William Cutbush (b.1785), who graduated from West Point in 1812 and attained eminence as an engineer, and James Cutbush (1788–1823), a renowned chemist,[7] who worked as a chemistry teacher, assistant surgeon and medical officer and died on December 15, 1823.[9]

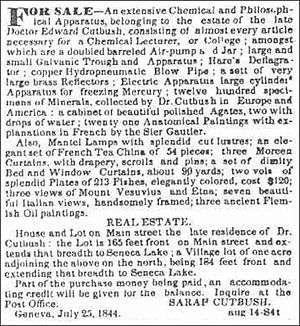

He married Ann "Nancy" Reynolds[5] (1768–1823) in 1795.[1] She was the daughter of James Reynolds, a woodcarver from Philadelphia.[7] After her death, he married Mrs. Sarah Rees, daughter of the late Mr. Josiah Twamley, merchant of Philadelphia. The marriage was announced on October 23, 1824. Cutbush was employed in the Medical Department of the Navy.[10]

Whiskey Rebellion

Cutbush began his career in the Pennsylvania Militia as hospital surgeon and later became surgeon general.[11] during the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion which took place in Western Pennsylvania and Maryland.[2] On September 22, 1794, Governor Mifflin appointed him as senior surgeon in the Hospital department for the militia of the state of Pennsylvania.[12]

Practical profession

The smallpox visited St. Louis, Missouri in 1801 about the time that the city became an American town. "In 1803 the doctors of Philadelphia, including Cutbush, had issued a circular to the whole profession, inculcating the virtue and duty of vaccination on April 12, 1803."[13] "We, the subscribers, physicians of Philadelphia, having carefully considered the nature and effects of the newly-discovered means of preventing, by vaccination, the fatal consequence of the smallpox, think it is a duty thus publicly to declare our opinion that inoculation for the kine or cowpox is a certain preventive of the smallpox, that it is attended with no danger, may be practiced at all ages and seasons of the year, and we do, therefore, recommend it for general use."[13]

Surgeon in U.S. Navy

He received his official naval commission as officer in the United States Navy on June 24, 1799 and was the first surgeon listed in the Naval Registry (and the only one listed as hired during the eighteenth century).[14] He was assigned to naval frigate, USS United States (1797).[3] Not long after, he made his first voyage to Europe when the ship carried an American delegation to negotiate an agreement to end America's quasi war with France.[3]

During the American War of Independence, the U.S. naval medical practice was limited to the use of "contract surgeons" who signed on to a ship for a single cruise. By 1801, Congress authorized half-pay for naval surgeons when they were in between duty, thereby ensuring stability in the Navy's medical ranks. Cutbush was the most prominent U.S. naval physician of this era.[2]

Throughout his long career, Cutbush saw extensive service in America, at sea, and abroad on missions to Spain, Italy, and North Africa. Cutbush participated in the 1802-1803 blockade of the Barbary ports in North Africa while serving on the USS Constitution. He was on duty at the bombardment of Tripoli in 1804.[3] He remained Surgeon in charge of NavalHospital Syracuse, Sicily 1904-1806.

During the War of 1812, he served at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and created a temporary hospital at New Castle, Delaware for the care of men assigned to gunboats in the Delaware Bay.[15]

By spring of 1813, he was transferred to Washington Naval Yard[15] and was granted charge and direction of the "Marine and Navy Hospital establishment and of the medical and hospital Stores, which may from time to time be required for the use of the hospitals, or for the vessels of the United States equipped at this place."[16] During his time there, which lasted until at least 1825, he was mentioned in Navy chronicles as "one of the ablest surgeons and physicians in our service."[17]

Cutbush served on the first board to examine candidates for the Navy's medical service.[3] The intent of the board was to examine Surgeon's Mates, "preparatory to their promotion to the rank of Surgeons." The board was also authorized to examine applicants for Commissions as Surgeons' Mates and report upon their fitness.[18]

Cutbush was the first American to employ lemon juice to prevent scurvy. He noted that "a ship furnished plentifully with lemon juice may bid defiance to the scurvy."[19] He was also an advocate of using leeches in the healing process. "After treatment, patients were removed from the cockpit to the adjacent gun room or the berth deck for observation, and the slightly wounded were ordered back to duty. If there was fever after surgery, Cutbush recommended a low diet and repeated bleedings as necessary. He believed that animal food was the best sustenance after wounding. Leeches were attached to the wound edges to reduce the swelling."[20]

By 1818, he was promoted to senior surgeon of the Navy. Because of his many contributions to nautical medicine he is regarded as "the Nestor of the Medical Corps of the Navy."[21]

Resignation from Navy

In 1828, Cutbush "publicly and fervently threw his support behind John Quincy Adams for re-election. Mere months after Adams lost his bout with Andrew Jackson, the medical veteran unexpectantly received orders to return to sea".[22]

He resigned on June 16, 1829,[23] after 30 years of service,[1] because he was ordered to serve on a vessel unsuitable to his rank.[7]

An editorial of the time in the New York Spectator, discussed how the Navy eliminated "extra allowance" given to officers, "which has reduced the pay of that branch of the service so low as scarcely to leave to the officers engaged in it the means to keep body and soul from divorcement."[24]

The article noted that Dr. Edward Cutbush was the oldest navy surgeon on the list and that he had "quietly been in service" for 30 years. "It was determined to get rid of this veteran, who had committed the great offense of not joining in the hurrah for Andrew Jackson. It is true; he took no part in the political contest, but contented himself with the performance of his duties as a citizen and an officer. But he was an offensive member of the service, and the quacks determined to amputate him."[24]

There was not "courage enough in the cabinet" to dismiss him, "lest the effect on other officers might be pernicious." Instead, he was given an order to report himself to the commanding officer of the station as surgeon on board the USS Constellation (1797), a frigate commanded by Captain Wadsworth that was going out to the Mediterranean.[24]

Cutbush appealed to the Secretary of the Navy in an attempt to revoke the order. "He informed the Secretary that at his advanced age, and with his impaired constitution, he could not live to reach the station. To send him out under these circumstances would be useless in a public view, as he would be incompetent to discharge the duties of the station." To this, the only answer he received was that the order could not be revoked, he must go.[24]

Cutbush then took another ground. As the oldest surgeon in the service, he had certain rights which belong to that rank. One of them was the right to a first rate ship (which apparently the Constellation was not). He also appealed that there were many young officers awaiting promotion who would be competent in the job, however, in his case, "although promotion was an ordinary process in the service, degradation in rank was a very extraordinary one. The Secretary could not, or would not understand his appeal. His reply was the same as before."[24]

"Upon this, Cutbush, disdaining further appeal, drew his commission from his pocket, and handed it to the secretary, and thus terminated the argument and interview together."[24] The newspaper article reported that "Dr. Cutbush of the navy, handed in his resignation yesterday, because he was ordered to duty, after a quiet and undisturbed residence of nineteen years in this city! A hard case indeed."[23]

Cutbush retired to Geneva, New York and put his talents to use as a Professor of Chemistry at Geneva College.[1]

Published works

During his long career as a navy surgeon, Cutbush wrote a pioneering book on the subject of military medicine called Observations on the Means of Preserving the Health of Soldiers and Sailors; and on the Duties of the Medical Department of the Army and Navy; With Remarks on Hospitals and their Internal Arrangement.[25] which was influential in the early ideas about military hygiene and preventive medicine. The pamphlet continued to be used by the military medical service during the War of 1812. In 1865, it was reprinted by the Massachusetts Temperance Alliance of Boston for distribution to Union Soldiers.[26] There were a total of four editions.[27] Today it is considered category rare books - non circulating.

One of the things Cutbush spoke out about in the book was his belief that the Navy should abandon the "flogging" of sailors.[28] The literature marked the beginning of much needed medical reform in both the Army and Navy.[29]

The Columbian Institute

Dr. Edward Cutbush founded The Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences, a Literary and Science Institution in Washington, DC.[30] Acknowledgements are also due to Thomas Law for the suggestion of such a society "at the seat of government."[30] It was the first "learned society" established in Washington and was organized on June 28, 1816,[31] less than two years after the invasion by the British troops.[30] The second article of its constitution states: " The Institute shall consist of mathematical, physical, moral and political sciences, general literature and fine arts."[31]

The society was chartered by Congress on April 20, 1818[31] for a term of twenty years.[30] Cutbush was the first president of the institution, however, by 1825, The Hon. John Quincy Adams held that title.[32]

The membership of the institute included many prominent men of the day, among them; John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay. In addition, many well-known representatives of the Army, the government service, medical and other professions.[30]

In 1820, President James Monroe set aside five acres for a "national greenhouse." Cutbush was one of the earliest crusaders for a plant repository and saw the necessity for a botanical garden "where various seeds and plants could be cultivated, and, as they multiplied, distributed to other parts of the Union."[33]

One of the greatest accomplishments of the society was the creation of a botanic garden in 1821. "By the end of 1823 the tract of land granted by Congress had been drained and leveled, an elliptical pond with an island at its center constructed, and four graveled walks laid out. Trees and shrubs were planted, and the garden was maintained as well as scanty funds would permit until the institute expired in 1837, one year before the termination of its charter."[34]

Cutbush's activities with the society ended when he left Washington in the late 1820s. "His enthusism evidently having begun to decline when it became apparent that substantial aid was not to be expected from the Government."[11]

The Columbian Institute's charter expired in 1838 and, in 1841, it was absorbed by the National Institute for the Promotion of Science.[35] The botanic garden ceased to operate in 1837 when the society stopped holding meetings. However it was re-instituted in 1842 when the Wilkes expedition of the South Seas brought back a collection of plants.[36]

The very tract of land the old garden occupied in 1837, was the site of the new United States Botanic Garden, established in 1850, thirteen years after the demise of the Columbian Institute.

The garden is located next to the Smithsonian Institution and a mere eighty feet from the steps of the U.S. Capitol Building. Currently, the tract is home to almost 10,000 living inhabitants, some of them over 165 years old.[33]

Columbian College

Cutbush was a Professor of Chemistry at Columbian College, located in the District of Columbia[37] from 1825 through 1827.[38] The college was instituted by an act of the United States Congress in the winter of 1821. Soon after, in 1824, the medical department was organized and professors appointed and by March, 1825, lectures commenced.[37]

Many years later, Columbian College was renamed to Columbia University and later to George Washington University.[39] Cutbush and his associates intended this university to be a national university.[39]

Geneva Medical College

Geneva Medical College was founded on September 15, 1834 after Trustees of Geneva College (now called Hobart and William Smith Colleges) approved the suggestion of Professor of Chemistry, Edward Cutbush, M.D., to create a medical school.[4] The institution was first known as the Medical Institution of Geneva College. It was the thirtieth medical school founded in North America and the seventh in New York State.[4]

Cutbush served as the first dean for the college from 1834 to 1839.[40] He was also Professor of Chemistry during his tenure at Geneva.[1]

Later life

By July 12, 1842, he was listed as a member of the Ontario County Medical Association of New York State in the association's annual report.[41]

Edward Cutbush died on July 23, 1843[42] in Geneva, New York at the age of 71.[38] He was buried in Pulteney Street cemetery in Geneva, New York and is still recognized there as a veteran of the United States armed forces.[43]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "New Jersey History". The New Jersey Historical Society, 2001. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Edward F. "Medical Practice in the Military.". Answers Corporation. Oxford University Press, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McCallum, Jack Edward. Military medicine: from ancient times to the 21st century. ABC-CLIO, 2008. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- 1 2 3 "Timeline History of SUNY Upstate Medical University". SUNY Upstate Medical Center. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- 1 2 3 Luft, Eric. "Bibliography Index" (PDF). Syracuse University. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ Paullo, Brenda. "Pennsylvania Marriages Prior to 1790". Pennsylvania Archives. USGenWeb Archives. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Edward F. "James Cutbush - An American Chemist (1788-1823)" (PDF). The University of Pennsylvania. J.B. Lippincott Company - Prometheus Publications, 1999. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ↑ "William Rush - Artist, Art". AskArt, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ↑ Segelquist, Dennis. "Civil War Days and those surnames". Segelquist. 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ↑ "Marriages.". New York Spectator (New York, New York). October 23, 1824.

- 1 2 Rathbun, Richard. The Columbian institute for the promotion of arts and sciences: A Washington Society of 1816-1838. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, October 18, 1917. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "Military abstracts from executive minutes". Electronic Library, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- 1 2 "Digitation Projects: The Medical Profession.". Published by George Clark, Boston, 1838. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ The Naval Monument: Containing Official and Other Accounts of All the Battles Fought Between the Navies of the United States and Great Britain. Published by George Clark, Boston, 1838. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- 1 2 Heidler, David S. & Jeanne T. Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland (2004). Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "Navy Board.". New York Spectator (New York, New York). June 11, 1824.

- ↑ Vitamin C in health and disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc, 1997. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ Kirkup, John (2005). The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century.

- ↑ "Developments of the Medical Office.". U.S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ↑ "Navy Medicine Enters the Political Arena" (PDF). The Grog Ration, December, 2008. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- 1 2 "Resignation.". Rome Reporter (Rome, New York). June 17, 1829.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Letter From Washington.". The Van Nuys News (Van Nuys, California). June 28, 1829.

- ↑ "Navy Medicine Comes Ashore". Oxford University Press, 1986. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ "Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers". Philadelphia : Printed for Thomas Dobson, Fry and Kammerer, printers, 1808. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ↑ "Edward Cutbush (Open Library)". Internet Archive, 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ↑ "Flogging in the Navy.". Department of the Navy, January 12, 2005. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ Pleadwell, Frank L., Capt. "Edward Cutbush, M.D.: The Nestor of the Medical Corps of the Navy." Annals of Medical History 5 (1923): page 367

- 1 2 3 4 5 Science - The Columbian Institute. New York, The Science Press, p.508, 1917. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- 1 2 3 "Thomas Law, a bibliographical sketch". Allen G. Clark, Washington, D.C. (1900). Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "The Columbian Institute.". New York Spectator (New York, New York). January 14, 1825.

- 1 2 "Our Nation's Greenhouse: The Mall, Washington, D.C." (PDF). Trumpet Vine, 2008. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ↑ "Greene: American Science in the Age of Jefferson.". Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "Columbian Institute's Records 1816-1841.". Smithsonian Institution Archives, February 3, 2003. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ↑ http://citycat.dclibrary.org/uhtbin/cgisirsi.exe/QWMC2f9na7/ML-KING/33270231/511/5327

- 1 2 "Medical School as described in an 1826 guidebook to Washington accessdate=2010-06-10". GWUEnclopedia. Special Collections Research Center Gelman Library, January 11, 2010.

- 1 2 Early American Chemical Societies. Appletons' Popular Science Monthly, 1897. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- 1 2 Haskin, Frederic J. (December 17, 1913). "University of the United States is Again Advocated.". Schenectady Gazette (Schenectady, New York).

- ↑ "History of the College of Medicine". SUNY Upstate Medical Center. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ↑ "Ontario County Medical Association". Conover’s History of Ontario Co., 2006. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ General alumni catalog of the University of Pennsylvania. The Alumni Association of the University, 1922. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ↑ "Veteran's Burials Decoration Day.". Geneva Daily Times, Geneva, N.Y., May 28, 1904. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

External links

- Penn Library: Smith Image Collection

- Naval Medicine in 1812. Mayer, Nancy

- The United States' naval chronicle, 1824

- Naval Register of 1826

- Penn's College and University Founders. Scott W. Hawley, 2002

- The Philadelphia medical and physical journal. Barton M.D., Benjamin Smith, 1808

- In Old Washington (Navy Yards), James Groggon Articles, Evening Star, November 12, 1910

- List of Officers, Dates of Commissions, and Length of Service at Sea Communicated to the House of Representatives, January 23, 1814

|