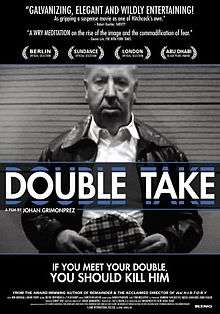

Double Take (2009 film)

| Double Take | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Johan Grimonprez |

| Produced by |

Nicole Gerhards Emmy Oost Hanneke M. van der Tas Denis Vaslin |

| Written by |

Johan Grimonprez Tom McCarthy |

| Music by | Christian Halten |

| Cinematography | Martin Testar |

| Edited by |

Dieter Diependaele Tyler Hubby |

Production company |

Zap-o-Matik |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country |

Belgium Germany Netherlands |

| Language | English |

Double Take is a 2009 essay film, directed by Johan Grimonprez and written by Tom McCarthy. The plot is set during the Cold War and combines both documentary and fictional elements. The protagonist is a fictionalised version of Alfred Hitchcock, who unwittingly gets caught up in a double take. The backdrop of the film charts the rise of the television in the domestic setting and with it, the ensuing commodification of fear during the cold war.[1]

Double Take is a Belgian-Dutch-German co-production and premiered in Europe at the 2009 Berlin Film Festival and in the U.S. at the 2010 Sundance film Festival.

Plot

Inspired by Jorge Luis Borges' short story 25th August, 1983,[2] Double Take's narrative plot is based on a fictional encounter Alfred Hitchcock has with an older version of himself. Whilst on set of his 1962 film The Birds, Hitchcock calls a twelve-minute break in order to answer a phone call in one of the universal studio buildings. After a foreboding encounter with a security guard, Hitchcock finds his way into a room similar to the tearooms in both the Chasen's hotel in Los Angeles and the Claridge's hotel in London. Here, Hitchcock and his doppelgänger meet.[3] The ensuing conversation between the two is characterized by personal paranoia and distrust where the younger Hitchcock is in deep fear of his older alter ego.

Intermittently returning to the room in which the menacing conversation between the two Hitchcocks proceeds,[4] the narrative takes a deathward path. Hitchcock and his doppelgänger regard each other with a mixture of revulsion and confusion. Regarding the aphorism that “if you meet your double, you should kill him”,[5] both Hitchcocks knowing how the encounter must end.[6]“So, tell me, how would you like to die?” asks the older Hitchcock, sipping on a cup of coffee. All the while, Folgers coffee advertisements puncture the narration in the backdrop of the Cold War. By means of his double, Hitchcock the filmmaker realizes that he is going to die. Killed by the younger, television-making, version of himself.[7]

Cast

- Ron Burrage as Hitchcock's Double.[8] "For years, Ron impersonated Hitchcock in everything ranging from Robert Lepage's Le Confessional (1995) (itself a remake), to soap and shampoo commercials, to guest appearances in music videos for Oasis, to introducing Hitchcock Presents on Italian television, to starring in a Japanese documentary about the life of the Master..."[9] However, Burrage shares much more with the real Alfred Hitchcock than his looks; from Hitchcock's pranks to his birthday (13 August). He is not only filling in for Hitchcock but literally taking over his role by introducing Tippi Hedren to the audience after the first screening of the newly restored print of The Birds in Locarno, that actually took place on 13 August.[9]

- Mark Perry as Hitchcock's Voice

- Delfine Bafort as the Hitchcock's blonde (the double of Eva Marie Saint and Tippi Hedren)

Looking for Alfred

In 2005, prior to making Double Take - which started as a casting,[10] Grimonprez shot the ten-minute video installation Looking For Alfred. The video installation explored the director's search for the perfect Hitchcock double. Grimonprez held screen tests in New York, Los Angeles and London.[11] He chose Mike Perry, a Hitchcock sound-alike and an impersonator of Tony Blair, while Ron Burrage, a professional Hitchcock double, as a result of this search, became a protagonist in Double Take.[10] The project explored the legacy of Hitchcock's persona as well as it made references to his films through restaging his cameo appearances. In 2007, Film and Video Umbrella published a book version of Looking For Alfred with inclusions by authors: Patricia Allmer, Jorge Luis Borges, Chris Darke, Thomas Elsaesser, Tom McCarthy, Jeff Noon and Slavoj Zizek.[12]

Themes

The themes of Double Take are paranoia, falsehoods, contradictions and the rise of the culture of fear played out through the beginning of the television era. Six major themes seem to surface:

- 1. Double Bottoms

- 2. The Commercial Break

- 3. Political Layaring

- 4. Reality versus Fiction

- 5. The Figure of the Double

- 6. Representation of Women

1. Double Bottoms and multilayered metaphors[10]

The multilayered metaphors of Double Take explore not only the character of Alfred Hitchcock meeting his double, but also the era's society as a whole.[10] Hitchcock is cast as a paranoid history professor shadowed by an elusive double against the backdrop of the Cold War, played out through the television tube; he "says all the wrong things at all the wrong times while politicians on both sides desperately clamor to say the right things, live on TV."[13] The themes explored in Double Take are all rooted in the following comment by Ron Burrage - the Alfred Hitchcock lookalike: “People always do a double take when they see me.”[14] And as such the film’s exploration into paranoia is also a double take on the Cold War, a mirror of the fear mongering played over the TV tube.

2. The Commercial Break

The five Folgers commercials for instant coffee that play throughout Double Take are referring to the commercial break of the television format, described by Hitchcock as "the enemy of suspense" and "designed to keep you from getting too engrossed in the story".[15] Moreover the commercials represent the exploration of the theme that fear and murder lurks in the domestic setting, “where it always belonged”. They also imply a yearning for successful 'falsehood'.[4] The question of why the Folgers housewives wouldn't simply prepare real coffee refers to the film's question why our culture yearns for successful imitation—for falsehood.[4] In this contradiction one act masquerades its opposite. The Folgers commercial is subverted in such a way that its message, “Drink Folgers,” becomes coded as part of a murder plot.[7]

3. Political Layering, The Cold War & The Birds as metaphor

Double Take presents the Soviet Union and the US as doubles in a series of power plays attempting to assure the other's demise.[5] Besides that Double Take is also about how two man always do the talking:[16] in the 'Kitchen Sink Debate' of 1959, the first televised summit live, Nikita Khrushchev outsmarted Richard Nixon, "whose best retort to the Soviet leader's critiques of U.S. capitalism is to point to the latest in TV sets".[17] Double Take implies that the predominate purposes of the space race as well as the television were propaganda, "both individually and, to greatest effect, when acting together".[18] The infamous 'Kitchen Sink Debate' mimics the conversation between Hitchcock versus Hitchcock, which mimics the man and woman debate in the kitchen during the Folgers commercials in turn.

The mirroring of Hitchcock versus Hitchcock (as Hitchcock frequently doubled himself as the storyteller in his films through his cameos),[9] suggests a similar doubling of Rixard Nixon and the young John F. Kennedy during the first televised presidential debates, the same Kennedy who finds his match in Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and finally Khrushchev versus Leonid Brezhnev just as Brezhnev is plotting Khrushchev's downfall.[19]

The paranoia in Hitchcock's work becomes an allegory for the kind of fear that became so normal during the Cold War.[5] Echoes of and excerpts from Hitchcock's The Birds (1963) propose the film as an allegory for television - which has, according to Hitchcock, "brought murder back into the home-where it always belonged",[18] and as the threat of missiles descending from the sky, suggesting a psychohistorical analogy between the fear of nuclear attack and Hitchcock's suspense.[18]

4. Reality vs Fiction

Double Take plays with different genres against one another and with how fiction comes to stand for reality or the other way around.[10] It shows a recent history against a fiction even while it presents that history itself as an ongoing story of claustrophobic suspense.[18] In the end not only politicians but Hollywood as well are "invested in perpetuating a culture of fear".[18] Double Take also refers to the doubling of cinema versus television through an intimate fiction story versus a bigger political narrative as well as through the rivalry between cinema and its televisual double. This mirrors the plot that sets up Hitchcock the filmmaker versus Hitchcock the television-maker at a time television was taking over cinema.[16]

But Double Take adds a contemporary twist: "You think all the way through that cinema is going to be killed by television or television is going to kill cinema or America is going to kill Russia or Russia is going to kill America. But at the end, it’s the third one, the new one, the younger one, the YouTube version, that comes along and kills them all."[16]

5. Cultural References: the Figure of the Double in Literature

Seeing ones own doppelganger is usually a bad omen, it might even be a "premonition of death".[9] The first narrated line during the 'Borgesian' confrontation between Hitchcock young and old in Double Take launches the plotline and comes with a warning: “If you meet your double, you should kill him.”[20] This provocative statement one should kill one's identical suggest that doing so means nothing but self-protection or even self-preservation.[2] For it is believed that the double has no reflection in the mirror, it can be seen as a mirror itself: "because he performs the protagonist's actions in advance, he is the mirror that eventually takes over."[9] Double Take is based on a similar plot.[9] Hitchcock himself gets eliminated in the first round of a Hitchcock lookalike competition. But all the participants of the competition áre Hitchcock, so "he's losing to himself".[7] Hitchcock studies are "proliferated to such a degree that there are many different Hitchcocks".[7] As Thomas Elsaesser notes that we now have a Hitchcock defined as Nietzschean and as Wittgeinsteinian, as Deleuzian and as Derridean, as Schopenhauerian and as many more contradictory things. In this way Hitchcock returns "as so many doubles of his own improbable self".[21]

Jose Luis Borges' initial short story August 25, 1983 is based on Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Double[2] as well as on Tom McCarthy's story Negative Reel in the book Looking For Alfred.[22] Authors like Adelbert von Chamisso, Hans Christian Andersen, Edgar Allan Poe and many more were inspired by the idea of the double as well.[23] The narration of Double Take is in fact already a double itself, for it is inspired by Borges' novella The Other (1972). Borges rewrote his novella into Agustus 25, 1983 (1983), and it was the latter one that was reworked for Double Take.[9]

6. Hitchcock's Belly Button, women and male hysteria

Hitchcock often portrays strong females leads, who according to Grimonprez mirror his own fears and phobias projected back onto the female character as a way to try to contain her, or even poison her.[9] Similarly, this male hysteria is also installed between man and man in Double Take.[16] Hitchcocks makes this confession in Double Take: "we always fell in love with our characters, that's why we killed them." Grimonprez claims that "Hitchcock wants the woman to embody his own desire, but his dreamwoman never redeems his anxiety precisely because she refuses to fit into that mould. The man then is ultimately faced with a split reality."[16] He is doubled, as it were. Just like the moment Sigmund Freud was confronted with his double during a train journey, when the door of the washing-cabinet swung back and Freud didn't recognize himself in the mirror. For a moment he believed someone entered his travelling compartment by mistake. He only realized that the man was nothing but his own reflection when he jumped up to show the stranger the right direction. Freud "thoroughly disliked his appearance".[24] Whereas this encounter with his double, an anxious feeling crept over him. According to Freud, "meeting one's double is an encounter with the uncanny, occurring at the boundaries between mind and matter and generating a feeling of unbearable terror."[16] The double, once a figure "endowed with life-supporting power",[2] transforms itself "into the opposite of what it originally represented. [...] It becomes "the uncanny harbinger of death"".[2][24]

In an interview with Karen Black, the last in a row of Hitchcock’s famous female protagonists who featured in Hitchcock’s final film Family Plot (1976), Black confirms to Grimonprez that the story about Hitchcock actually not having a belly button was true.[25] This story became part of the plotline in the film Hitchcock didn’t have a Belly Button. "If Hitchcock didnt have a belly button he might be a clone and there might actually be many doubles of the master, of which Ron Burrage was one", wrote Grimonprez.[25]

In Hitchcock didn’t have a Belly Button Black does expressions of Hitchcock. And as she is pretending to be Hitchcock she becomes his vocal double. Jodi Dean writes on his blog I Cite that we experience two people but one voice: "we hear the one who is speaking and know that it is him, but we also hear another - only rarely do we mistake one for the other, we know the difference".[26]

Release & Critical Reception

Double Take premiered in Europe at the Berlinale[27] and in the US at Sundance. The film was screened at several film festivals, including IDFA.[28] Double Take was released on DVD by Soda Pictures[29] in England and Kino Lorber[30] in the United States. It was acquired for TV release by ARTE in 2011.

Variety described Double Take as "wildly entertaining",[17] the New York Times called it "the most intellectually agile of this year’s films"[31] and the Hollywood Reporter found the film "bracingly original", assuming that it "would have tickled Hitch himself".[32] John Waters mentioned Double Take as "My top 10!" in Art Forum and Screen described the film as "Ingenious, witty, virtuoso!".[33]

Double Take is part of the permanent collections of the Tate Modern (Artist Rooms) and Centre Pompidou, amongst others. It was screened at the New Directors/New Films Festival (presented by The Film Society of Lincoln Center) and The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA.

Awards

- Black Pearl Award for Best Documentary Director, Abu Dhabi International Film Festival[34][35]

- Grand Prize, New Media Film Festival, Los Angeles[36]

- Special Mention, Era New Horizons International Film Festival, Warsaw

- Special Mention, Image Forum Festival, Yokohama

- Film of the Month, Sight & Sound

References

- ↑ "Double Take Synopsis".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nobus, D. (October 15, 2009). Borges' and Hitchcock's Double Desire. Arts Centre Vooruit, Ghent, Belgium: Paper presented at the symposium "Shot by Both Sides! Double take".

- ↑ McCarthy, T. (2009). Double Take - Narration of the Film. Inspired by the short story "August 25, 1983" by J. L. Borges.

- 1 2 3 Princenthal, Nancy (May 2009). "Think Again" (PDF). Art in America. No. 5.

- 1 2 3 Cabin, Chris. "Double Take" (PDF). AMCFilmcritic.com. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ↑ Zutter, Natalie. "'Double Take' Provides Layered Look at Cold War Paranoia" (PDF). ...Ology.com. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Provan, Alexander (July 15, 2009). "If you see yourself, kill him" (PDF). Bidoun.

- ↑ "IMDB profile of Ron Burrage".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Darke & Grimonprez, Chris & Johan (2007). Looking For Alfred : Hitchcock is not himself today... An interview with Johan Grimonprez by Chris Darke. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz. pp. 77–99. ISBN 978-1-9042-7025-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 van Tomme, Niels (May–June 2009). "Constructing Histories: Johan Grimonprez discusses "Double Take"" (PDF). Art Papers.

- ↑ "Johan Grimonprez: Looking for Alfred". e-flux. Retrieved December 10, 2004.

- ↑ "Film and Video Umbrella".

- ↑ "Double Take". Johan Grimonprez website.

- ↑ Reynaud, Bérénice. "On the use and misuse of archival footage – Part 1 – Johan Grimonprez’s Double Take (Frontier)". Retrieved July 2010.

- ↑ Romney, Jonathan. "Film of the month: Double Take". Sight & Sound.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bernard & Grimonprez, Catherine & Johan (2010). "It's a poor sort of memory that only works backwards: Johan Grimonprez en dialogue avec Catherine Bernard". L'image-document, entre réalité et fiction, ed. J.-P. Criqui (Paris: Le Bal/Marseille: Images en Manoeuvres Editions): 212–23.

- 1 2 Robert, Koehler. "Review: 'Double Take’". Variety. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Scrimgeour, Alexander (April 2009). "1000 Words, Johan Grimonprez talks about Double Take" (PDF). Artforum.

- ↑ Dean, J. (October 15, 2009). The Real Double. Arts Centre Vooruit, Ghent, Belgium: Paper presented at the symposium "Shot by Both Sides! Double Take".

- ↑ Peranson, Mark. "Interviews | If You Meet Your Double, You Should Kill Him: Johan Grimonprez on Double Take". Cinema Scope.

- ↑ Elsaesser & Grimonprez, Thomas & Johan (2007). Looking for Alfred : Casting Around: Hitchcock's Absence. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz. pp. 137–161. ISBN 978-1-9042-7025-6.

- ↑ McCarthy & Grimonprez, Tom & Johan (2007). Looking for Alfred : Negative Reel. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz. pp. 65–71. ISBN 978-1-9042-7025-6.

- ↑ Goimard & Stragliati, Jacques & Roland (1977). Histoires de Doubles. Paris: Presses Pocket. ISBN 2266003844.

- 1 2 Sigmund, Freud (1955). "The Uncanny". The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 17: 248.

- 1 2 Grimonprez, Johan. "Hitchcock didn’t have a Belly Button: Karen Black interview with Johan Grimonprez". Retrieved 2009.

- ↑ Dean, Jodi. "A voice as something more". I Cite. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Berlinale".

- ↑ "IDFA".

- ↑ "Soda Pictures".

- ↑ "Kino Lorber".

- ↑ Lim, Dennis (February 13, 2009). "Multinational Forces at the Berlin Film Festival" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ↑ Lowe, Justin. "Double Take -- Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ↑ Romney, Jonathan. "Double Take" (PDF). Screen. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ "VAF".

- ↑ "Abu Dhabi Film Festival".

- ↑ "Bamart".

External links

- Official website

- Double Take at the Internet Movie Database

- Borges' and Hitchcock's Double Desire

- This Long Century

- I Cite

- The Kitchen Debate: First Televised Summit

- Mr. Hitchcock would like to say a few words

- Double Take Trailer