Double play

In baseball, a double play (denoted on statistics sheets by DP) for a team or a fielder is the act of making two outs during the same continuous playing action. In baseball slang, making a double play is referred to as "turning two" or a "twin killing".

Double plays are also known as "the pitcher's best friend" because they disrupt offense more than any other play, except for the rare triple play. Pitchers often select pitches that make a double play more likely (typically a pitch easily hit as a ground ball to a middle infielder) and teams on defense alter infield positions to make a ground ball more likely to be turned into a double play. Because a double play ends an inning in a one-out situation, it often makes the scoring of a run impossible in that inning. In a no-out situation with runners at first base and third base, the double play may be so desirable that the defensive team allows a runner to score from third base so that two outs are made and further scoring by the batting team is more difficult.

Scoring of double plays

Double plays in which both outs are recorded by force plays or the batter-runner being put out at first base are referred to as "force double plays".[1] Double plays in which the first out is recorded via a force play or putting the batter-runner out at first base and the second out by tagging a runner who would have been forced out but for the first out (as when a first baseman fields a ground ball, steps on first base, and then throws to second) are referred to as "reverse force double plays". Should a run score on a play in which a batter hits into either a force double play or a reverse force double play, the official scorer may deny the batter credit for an RBI, although the batter always gets credit for an RBI on a one-out groundout or a fielder's choice play in which a baserunner scores.

Records of double plays were not kept regularly until 1933 in the National League and 1939 in the American League. Double plays initiated by a batter hitting a ground ball (but not a fly ball or line drive) are recorded in the official statistic GIDP (grounded into double play).

Types of double plays

Common double plays

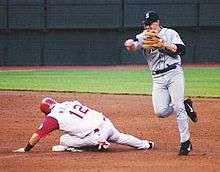

The most common type of double play occurs with a runner on first base and a ground ball hit towards the middle of the infield. The player fielding the ball (generally the shortstop or second baseman) throws to the fielder covering second base, who steps on the base before the runner from first arrives to force that runner out, and then throws the ball to first base to put out the batter-runner for the second out. If the ball originated with the shortstop and was then thrown to the second baseman, the play is referred to as a "6-4-3 double play", after the numbers assigned to the players in order of field position; if it is hit to the second baseman and then thrown to the shortstop, it is known as a 4-6-3 double play (6-shortstop, 4-second base, 3-first base; see baseball positions). A slightly less common ground ball double play is the 5-4-3 double play, also called the "Around the Horn" double play which occurs on a ground ball hit to the third baseman (5), who throws to the second baseman (4) at second base, who then throws to the first baseman (3). Comparatively few third basemen succeed often at turning such double plays which require a third baseman with good range and a great throwing arm. Rarer still is a 4-3-6 or 6-3-4 double play in which a middle infielder throws first to the first baseman to retire the batter and the first baseman then throws to the other middle infielder who tags the runner from first base (the force situation having been removed when the batter was put out).

It is also possible for an infielder (usually the second baseman or shortstop) or catcher to field a ground ball, touch the base that he is closest to (getting an out) and then throwing to first base. For a third baseman this play is unlikely because it requires a force play at third base that requires runners at first and second base. For a catcher this is extremely rare because it requires that the bases be loaded so that the catcher has a force play at the plate and a ground ball hit so feebly that the catcher can easily field it. Such plays are scored 2-3 (catcher to first baseman), 4-3 (second baseman to first baseman), 5-3 (third baseman to first baseman), or 6-3 (shortstop to first baseman).

Unassisted double plays are more common than unassisted triple plays. The typical scenario includes an infielder catching a line drive and stepping on a base to double off a runner. Rarer is a scenario where an infielder tags two runners on the same play.

Double plays also occur on ground balls hit to the pitcher. Most of the time, these double plays will go 1-6-3 (pitcher to shortstop to first baseman), though sometimes these double plays will go 1-4-3 (pitcher to second baseman to first baseman). 6-3 and 4-3 double plays occur on ground balls to the shortstop or second baseman, respectively, which the fielder takes for an unassisted putout at second before throwing to first. The 3-6-3 double play occurs on a ground ball to the first baseman, who throws to the shortstop at second base before stepping on first. Thus, the shortstop can throw back to the first baseman, who is still able to get the putout at first. Variants of this double play include the 3-6-1 double play (where the pitcher covers first) and the 3-6-4 double play (where the second baseman covers first). Also, the first baseman may choose to retire the batter at first before throwing to the shortstop at second, who then tags the runner coming from first (tag because the force has been removed). More rare double plays include the 1-6-4-3, and the 1-4-6-3 double play. In these, the pitcher will "kick-save" the ball (instinctively knocking down the batted ball with his foot), or the ball will deflect off some other part of the pitcher's body.

Another class of double plays include those in which infielders catch line drives and then throw or run to a base to catch a baserunner who fails to return to the base from which he has started. The batter is out because his ball has been caught on the fly, and a runner is out at another base. For example, if a batter hits a line drive to the second baseman (or any other infielder, or the pitcher) that a baserunner from first base thinks is a clean hit and the second baseman catches before it drops, then the second baseman can throw to first base to the fielder (usually the first baseman) covering the base; should the first baseman either touch first base with any part of his body (usually his feet) or tag the baserunner returning to first (not necessary), then a double play is completed. More rare is an unassisted double play in which the fielder catches a line drive and either tags a runner off base or tags a base that a baserunner cannot return to on time.

A "strike 'em out, throw 'em out" double play requires that a base runner is caught stealing immediately after the batter strikes out. The batter is out on a called or swinging third strike while the runner is caught (typically for this play the shortstop). Such is a 2-6 double play unless a rundown ensues or the play is made at some base other than second base. The catcher gets a putout for the strikeout and an assist for the throw that leads to the caught stealing.

On occasion, bad bunts can result in double plays. An attempted sacrifice bunt may be laid down such that a charging pitcher, first baseman or catcher (the typical initiators of such plays) is able to field the ball, throw to second base to force a runner out, and the shortstop (the usual fielder at second base on a bunt play) then is able to throw to the fielder covering first base (usually the second baseman) to put out the batter. With a runner on first base, should the batter bunt a ball fair as an infield fly, the infield fly rule that protects baserunners is no longer applicable. At his discretion, the fielder in position to catch the bunted fly ball may elect to 'trap' the fly ball (that is, put his glove on the ground but over the ball to secure it) or (a fielder is not allowed to drop a ball deliberately to force runners to advance) catch it on a short bounce, in which case the runner at first must reach second base before a throw is made to second base. The fielder covering second base can throw to first base to complete the double play. Should the runner at first stray too far from first base, however, and the infielder catches the pop fly, the infielder gets the out for catching an infield fly and throws to first base to complete the double play.

Rare double plays

Another double play occurs when a fly ball is hit to the outfield and caught, but a runner on the basepath strays too far away from his base. If the ball is thrown back to that base before the runner returns or tags up to go to the next base, the runner is out along with the batter for a double play.

A strike-'em-out-throw-'em-out double play at third base is rare, and an unassisted double play by the catcher on a play in which a baserunner tries to steal home base on a straight steal during a strikeout is highly unlikely. It is possible that a risky baserunning play will ensue during a strikeout in which a baserunner attempts to score from third base on a successful steal of second or a rundown play in which an infielder or pitcher throws to the catcher who then tags a runner trying to score, in which case the catcher gets two putouts (one for the strikeout and one for the tag play at home) and one assist for a throw to the infield. A catcher might also initiate a double play on a strikeout that begins with a dropped third strike and a throw to first to put out the batter-runner and a baserunner attempts to reach third or home on an attempted steal.

Two others involve outfield flies: more commonly, a baserunner tags up from third base on an outfield fly, attempting to score before a throw from the outfielder (more rarely an infielder) can be thrown to the catcher. Should the catcher tag the runner before he can score, the play is considered a double play, and the outfielder is credited with an assist. Similar plays can be made at second base or third base, or in rundown plays on the infield. Many outfield assists are made on such plays, and the most assists made in any given year by a single outfielder is typically about twenty (they need not be made on double plays).

Far rarer is a play in which the runner attempts to advance before the outfielder catches the fly ball. As a rule the double play is completed after the pitcher receives the ball and throws to the base that the runner has left too soon; on appeal the base-runner who left the base too early is called out on the play.

A rare double play that can only take place with the bases loaded is a play in which a sharply-hit ball is fielded by an infielder, who throws to home to force the runner coming in from third. The catcher then throws the ball to the fielder covering first base to retire the batter. Such a double play ended the top half of the 8th inning during Game 7 of the 1991 World Series: With one out and the bases loaded, Atlanta's Sid Bream hit a ground ball at Twins first baseman Kent Hrbek, who fielded it and threw it to catcher Brian Harper to retire Lonnie Smith at home. Harper then threw back to Hrbek to retire the side. Another variation of this play, in which the pitcher, and not an infielder, first fields the ground ball is the "1-2-3 double play." Such a play occurred in the no-hit shutout that Jack Morris pitched in 1984.[2]

A unique double play likely never to happen again in MLB; a 9-2-7-2 that effectively ended a career. On July 9, 1985 with Phil Bradley, a 3 times Big Eight decorated University of Missouri football player, on second Gorman Thomas singles to right. Jesse Barfield, with an arguably the strongest arm of the 80's, charged the ball and fired slightly up the line to Buck Martinez who had just enough time to catch the ball before absorbing Bradley's full charge. A broken leg and severely dislocated ankle but he held on. Attempting to catch Thomas rounding second Martinez, now seated and severely injured, threw the ball into left field. On the error Thomas rounds third attempting to score. George Bell (outfielder) now in shallow left field to the line quickly returns the ball to Martinez, on a hop, who applies a tag on a scrambling Thomas. The play effectively ended Buck's playing career but is arguably the greatest character play you'll ever see and one of strangest double play in MLB history. [3] [4] [5]

A bizarre double play occurred in a nationally televised game between the New York Yankees and Chicago White Sox on August 2, 1985 when both Bobby Meacham and Dale Berra were tagged out at home by Carlton Fisk on a deep drive single to left-center by Rickey Henderson. An identical situation would occur again in the 2006 NLDS between the Dodgers and Mets when Russell Martin hit a single to right field and Paul Lo Duca tagged out Jeff Kent and J.D. Drew at the plate.

An unusual double play occurred on April 12, 2008, Yankees at Red Sox. The infield was shifted right for Jason Giambi, with a baserunner on first. Giambi grounded to 2nd baseman Dustin Pedroia, who threw to the 3rd baseman Kevin Youkilis, who because of the shift actually had to cover 2nd base. Youkilis tagged second, then turned the DP by throwing to 1st baseman Sean Casey, to get Giambi out. This would therefore be a rare "4-5-3" double play. A similar double play occurred in the interleague game in Nippon Professional Baseball on June 14, 2009, where Hiroshima Toyo Carp against Saitama Seibu Lions, which Carp placed a five-man infield with left fielder covered the place between pitcher and 2nd base, and finally grounded into a rare "7-2-3" double play when the ball grounded to the shifted man.[6] The Chicago Cubs turned a 7-2-3 double play against the Pirates on Apr 2, 2014.

Another rare double play includes interference, where an offensive player hinders a defensive player's attempt at throwing the ball to make an out. Such a double play happened on July 24, 2000 in a game between the Anaheim Angels and the Texas Rangers. In the first inning, Mo Vaughn of the Angels struck out swinging, and the Ranger catcher Pudge Rodriguez attempted to throw out Kevin Stocker, who was trying to steal 2nd base. In his follow through, Rodriguez's hand hit Vaughn's bat, preventing him from making an accurate throw to 2nd base. Home plate umpire Gerry Davis called Stocker out at 2nd due to batter's interference. Scoring wise, the play went as a strike out for the pitcher Kenny Rogers, an unassisted double play for Rodriguez, and batter's interference on Vaughn.

On May 27, 2011, the AA New Britain Rock Cats had a double play against the Binghamton Mets involving seven defenders. With runners on second and third, a ground ball was hit to the first baseman. The first baseman threw to the catcher to tag the runner from third. The catcher chased the runner back to third. By then, the runner from second was most of the way to third, so the catcher threw to the shortstop. Then the runner from third tried to go home again so the shortstop threw to the pitcher now covering home, who then threw to the third baseman who got the runner out. At this point, the batter was between first and second, so the third baseman threw to the first baseman to chase him down. He threw to the second baseman. Then the runner from second ran again, so the second baseman threw to the shortstop. The shortstop threw to the center fielder now covering second, who tagged the runner for the second out. The play was scored as a 3-2-6-1-5-3-4-6-8 double play.[7][8][9]

Strategy

Highly desirable to the pitching team and highly undesirable to the batting team, the double play often proves critical to wins and losses of specific games. The pitching team is likely to change pitch selection and defensive alignment to make one of the more common double plays (the ones involving infield ground balls) more likely. Batting teams may adapt themselves to thwart or even exploit the situation.

A so-called double-play position involves the second baseman and shortstop moving away from second base so that one of the fielders can field a ground ball and the other can run easily to second base to catch a ball thrown to him so that he can tag the base before the baserunner from first base can reach second base, the infielder tagging second base then throwing to first base to complete the double play. The pitcher tries to throw a pitch in the strike zone that, if hit, is likely to be grounded to an infielder (or the pitcher) and turned into a double play.

In a situation with runners on second and third and fewer than two outs, a team may decide to give an intentional pass to a hitter, often a slow baserunner who is perceived as one of the more dangerous hitters on the team or to the pitcher. A double play is then possible on a ground ball to a middle infielder. However:

(1) a subsequent walk scores a run, and

(2) the batter reaching first base on the intentional walk may score on subsequent plays should no outs be made.

This situation allows a great reward to the pitching team should it succeed in inducing a double play (far less opportunity of scoring) but also great reward to the batting team should it fail.

Batting teams can select lineups to reduce the likelihood of double plays by alternating slow right-handed hitters with left-handed hitters or hitters who are fast baserunners, or by putting a slow-running slugger (typically a catcher) in a low spot in the batting order (often #7 where there is no designated hitter). In a situation where a double play is possible, the batting team can

- attempt to steal second base if it is unoccupied (but only with a fast baserunner)

- sacrifice bunt, which concedes an out but advances the baserunner and prevents a double play

- either avoid swinging at pitches likely to become infield ground outs or foul them off

- avoid pulling the ball (a ground ball "pulled" by a right-handed batter to the left side of the infield is a likely double-play ball)

- hit and run, a play in which the baserunner on first runs to second immediately after the pitch is thrown in the hope that the batter makes contact with the pitch

- try to hit the ball as a long fly ball, ideally a home run

All of these strategies entail risk and may be either inappropriate or impossible, depending on the situation. A stolen base attempt ensures that the runner on first base is either at second (making a double play impossible) or out (likewise, but with an out and the loss of a baserunner). Some batters cannot bunt well, and poor bunts can themselves result in double plays. Avoiding the double-play pitch may mean taking a called strike. Trying not to pull the ball decreases the possibility of a home run that scores two or more runs. The hit-and-run play requires that the batter hit the ball, lest the baserunner be caught stealing on a throw from the catcher to the shortstop or second baseman covering second base and makes a pick-off of a baserunner more likely. A strikeout-prone hitter who swings wildly in the hope of getting a pitch that he can hit as a long fly ball as a sacrifice fly, double, triple, or home run is more likely to strike out.

Because the rarer double plays require baserunning errors, no team relies upon them to get out of a bad situation unless the opportunity arises. Even extreme strikeout pitchers such as Randy Johnson or Pedro Martínez sometimes have to rely on double plays to be effective.

The ability to "make the pivot" on an infield double play, i.e. receive a throw from the third-base side, then turn and throw the ball to first in time to force-out the batsman, while avoiding being "taken out" by the runner, is considered to be a key skill for a second baseman.

Cal Ripken, Jr. holds the major league record for most double plays grounded into in a career, with 350. He also holds the American League record for most double plays made by a shortstop. Both records are a consequence of his longevity as a player and the long grass at the Baltimore baseball stadium (Camden Yards and Memorial Stadium) as well as an accurate and strong throwing arm that allowed him to start more double plays than most other shortstops. As a batter, Ripken was a slow baserunner throughout his career, so he was less likely to reach base safely on a ground ball hit to the infield. A reasonably powerful right-handed hitter who frequently hit near the middle of the batting order and did not strike out at a high rate, he frequently came to the plate with runners on base, and usually made solid contact (as opposed to bunting) to usually put the ball in play. More likely to hit the ball sharply to the left side of the infield, placed in the order of the lineup so that he usually had runners on base ahead of him, and less likely to beat throws to first base, and having a very long career because he was a good hitter for average and power, this competent hitter grounded into an unusual number of double plays.

A batter who grounded into comparatively few double plays (72 in his long career) was Kirk Gibson, a left-handed hitter and a fast runner who struck out often but largely hit fly balls and hit few ground balls. As a left-handed hitter, if he pulled the ball and put it on the ground, he usually pulled the ball to the right side of the infield. To complete a double play on a ground ball that he did hit, a team had to complete the usually-difficult 3-6-3 or 3-6-1 double play; Gibson would usually reach first base before the double play could be completed in part because the 3-6-3 and 3-6-1 double plays take two long throws and in part because as a left-handed hitter he had a slightly-shorter run to first base. Like Ripken he was a power hitter usually batting in the middle of the batting order and often with runners on first base; unlike Ripken he hit far fewer balls toward fielders who could turn double plays upon him and struck out far more often, his strikeouts making a GIDP impossible.

All-time single season double play leaders by position

First Base

- Ferris Fain: 194 (Philadelphia A's 1949)

- Ferris Fain: 192 (Philadelphia A's 1950)

- Donn Clendenon: 182 (Pittsburgh Pirates 1966)

- Andrés Galarraga: 176 (Colorado Rockies 1997)

- Ron Jackson: 175 (Minnesota Twins 1979)

- Albert Pujols: 175 (St. Louis Cardinals 2005)

- Gil Hodges: 171 (Brooklyn Dodgers 1951)

- Mickey Vernon: 168 (Cleveland Indians 1949)

- Carlos Delgado: 167 (Toronto Blue Jays 2001)

- Ted Kluszewski: 166 (Cincinnati Reds 1954)

Second Base

- Bill Mazeroski: 161 (Pittsburgh Pirates 1966)

- Jerry Priddy: 150 (Detroit Tigers 1950)

- Bill Mazeroski: 144 (Pittsburgh Pirates 1961)

- Dave Cash: 141 (Philadelphia Phillies 1974)

- Nellie Fox: 141 (Chicago White Sox 1957)

- Carlos Baerga: 138 (Cleveland Indians 1992)

- Bill Mazeroski: 138 (Pittsburgh Pirates 1962)

- Buddy Myer: 138 (Washington Senators 1935)

- Red Schoendienst: 137 (St. Louis Cardinals 1954)

- Jackie Robinson:137 (Brooklyn Dodgers 1951)

- Jerry Coleman: 137 (New York Yankees 1950)

Shortstop

- Rick Burleson: 149 (Boston Red Sox 1980)

- Roy Smalley: 144 (Minnesota Twins 1979)

- Bobby Wine: 137 (Montreal Expos 1970)

- Lou Boudreau:134 (Cleveland Indians 1944)

- Spike Owen: 133 (Seattle Mariners/Boston Red Sox 1986)

- Rey Sánchez: 130 (Kansas City Royals/Atlanta Braves, 2001)

- Rafael Ramirez: 130 (Atlanta Braves 1982)

- Jack Wilson: 129 (Pittsburgh Pirates, 2004)

- Roy McMillan: 129 (Cincinnati Reds 1954)

- Gene Alley: 128 (Pittsburgh Pirates 1966)

- Vern Stephens: 128 (Boston Red Sox 1949)

- Hod Ford: 128 (Cincinnati Reds 1928)

Third Base

- Graig Nettles: 54 (Cleveland Indians 1971)

- Harlond Clift: 50 (St. Louis Browns 1937)

- Johnny Pesky: 48 (Boston Red Sox 1949)

- Paul Molitor: 48 (Milwaukee Brewers 1982)

- Sammy Hale: 46 (Philadelphia A's 1927)

- Clete Boyer: 46 (New York Yankee 1965)

- Gary Gaetti: 46 (Minnesota Twins 1983)

- Eddie Yost: 45 (Washington Senators 1950)

- Frank Malzone: 45 (Boston Red Sox 1961)

- Darrell Evans: 45 (Atlanta Braves 1972)

- Jeff Cirillo: 45 (Milwaukee Brewers 1998)

Catcher

- Steve O’Neill: 36 (1917)

- Frankie Hayes: 29 (1945)

- Yogi Berra: 25 (1951)

- Ray Schalk: 25 (1916)

- Tom Haller: 23 (1968)

- Muddy Ruel:23 (1924)

- Jack Lapp: 23 (1915)

- Bob O’Farrell: 22 (1922)

- Steve O’Neill: 22 (1914)

- Wes Westrum: 21 (1950)

- Gabby Hartnett: 21 (1927)

Pitcher

- Bob Lemon: 15 (Cleveland Indians, 1953)

- Randy Jones: 12 (San Diego Padres, 1976)

- Curt Davis: 12 (Philadelphia Phillies, 1934)

- Eddie Rommel: 12 (Philadelphia Athletics, 1924)

- Kirk Rueter: 11 (San Francisco Giants, 2001)

- Gene Bearden: 11 (Cleveland Indians, 1948)

- Burleigh Grimes: 11 (Brooklyn Dodgers, 1925)

- Art Nehf: 11 (New York Giants, 1920)

- Scott Perry: 11 (Philadelphia Athletics, 1919)

- Tom Rogers: 11 (Philadelphia Athletics, 1919)

Left Field

- Jimmy Sheckard: 12 (Chicago Cubs, 1911)

- Max Carey: 10 (Pittsburgh Pirates, 1912)

- Alfonso Soriano: 9 (Washington Nationals, 2006)

- Duffy Lewis: 9 (Boston Red Sox, 1910)

- Harry Stovey: 9 (Philadelphia Athletics, 1889)

- Kip Selbach: 8 (New York Giants, 1900)

- Ed Delahanty: 8 (Philadelphia Phillies, 1893) [*includes 17 games in CF]

- Albert Belle: 7 (Cleveland Indians, 1993)

- Zack Wheat: 7 (Brooklyn Superbas, 1913)

- Sherry Magee: 7 (Philadelphia Phillies, 1907)

- Joe Kelley: 7 (Brooklyn Superbas, 1899)

- Jesse Burkett: 7 (Cleveland Spiders, 1892)

- Billy Hamilton: 7 (Philadelphia Phillies, 1892)

- Billy Hamilton: 7 (Philadelphia Phillies, 1891)

Center Field

- Happy Felsch: 15 (Chicago White Sox, 1919)

- Tom Brown: 13 (Louisville Colonels, 1893)

- Mike Griffin: 12 (Brooklyn Grooms, 1895)

- Cy Seymour: 12 (Cincinnati Reds, 1905)

- Ginger Beaumont: 12 (Boston Doves, 1907)

- Tris Speaker: 12 (Boston Red Sox, 1909)

- Tris Speaker: 12 (Boston Red Sox, 1914)

- Bill Lange: 11 (Chicago Orphans, 1899)

- Fielder Jones: 11 (Chicago White Sox, 1902)

- Ben Koehler: 11 (St. Louis Browns, 1905)

- Burt Shotton: 11 (St. Louis Browns, 1913)

Right Field

- Jimmy Sheckard: 14 (Baltimore Orioles, 1899)

- Tom Brown: 12 (Pittsburgh Alleghenys, 1886)

- Tommy McCarthy: 12 (St. Louis Browns, 1888)

- Jimmy Bannon: 12 (Boston Beaneaters, 1894)

- Danny Green: 12 (Chicago Orphans, 1899)

- Ty Cobb: 12 (Detroit Tigers, 1907)

- Mel Ott: 12 (New York Giants, 1929)

- Sam Thompson: 11 (Detroit Wolverines, 1886)

- Tommy McCarthy: 11 (St. Louis Browns, 1889)

- Sam Thompson: 11 (Philadelphia Phillies, 1896)

- Jimmy Sebring: 11 (Pittsburgh Pirates, 1903)

- Chief Wilson: 11 (St. Louis Cardinals, 1914)

References

- ↑ "Baseball Almanac - Baseball Rules". Retrieved 2012-05-10.

- ↑ Baseball-Reference April 7th, 1984

- ↑ YouTube, 9-2-7-2 double play

- ↑ Epic Games in Blue Jays History: Buck Martinez Completes a Double Play on a Broken Leg

- ↑ The greatest play ever made

- ↑

- ↑ Scoreboard on milb.com

- ↑ Crazy double-play on Yahoo! videos

- ↑ New Britain Rock Cats crazy double play

- Bibliography

- James, Bill (2002). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- Career GIDP leaders, Baseball-Reference.com