Doppler imaging

Inhomogeneous structures on stellar surfaces, i.e. temperature differences, chemical composition or magnetic fields, create characteristic distortions in the spectral lines due to the Doppler effect. These distortions will move across spectral line profiles due to the stellar rotation. The technique to reconstruct these structures on the stellar surface is called Doppler-imaging, often based on the Maximum Entropy image reconstruction to find the stellar image. This technique gives the smoothest and simplest image that is consistent with observations.

To understand the magnetic field and activity of stars, studies of the Sun are not sufficient. Therefore, studies of other stars are necessary. Periodic changes in brightness have long been observed in stars which indicate cooler or brighter starspots on the surface. These spots are larger than the ones on the Sun, covering up to 20% of the star. Spots with similar size as the ones on the Sun would hardly give rise to changes in intensity. In order to understand the magnetic field structure of a star, it is not enough to know that spots exist because their location and extent are also important.

History

Doppler imaging was first used to map chemical peculiarities on the surface of Ap stars. For mapping starspots it was first used by Steven Vogt and Donald Penrod in 1983, when they demonstrated that signatures of starspots were observable in the line profiles of the active binary star HR 1099 (V711 Tau); from this they could derive an image of the stellar surface.

Criteria for Doppler Imaging

In order to be able to use the Doppler imaging technique the star needs to fulfill some specific criteria.

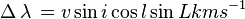

- The stellar rotation needs to be the dominating effect broadening spectral lines,

.

.

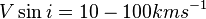

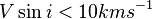

- The projected equatorial rotational velocity should be at least ,

. If the velocity in lower, spatial resolution is degraded, but variations in the line profile can still give information of areas with higher velocities. For very high velocities ,

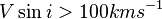

. If the velocity in lower, spatial resolution is degraded, but variations in the line profile can still give information of areas with higher velocities. For very high velocities ,  ., lines become too shallow for recognizing spots.

., lines become too shallow for recognizing spots.

- The inclination angle, i, should preferably be between 20˚-70˚.

- When i =0˚ the star is seen from the pole and therefore there is no line-of-sight component of the rotational velocity, i.e. no Doppler effect. When seen equator-on, i =90˚ the Doppler image will get a mirror-image symmetry, since it is impossible to distinguish if a spot is on the northern or southern hemisphere. This problem will always occur when i ≥70˚; Doppler images are still possible to get but harder to interpret.

Theoretical Basis

In the simplest case, dark starspots decrease the amount of light coming from one specific region; this causes a dip or notch in the spectral line. As the star rotates the notch will first appear on the short wavelength side when it becomes visible towards the observer. Then it will move across the line profile and increase in angular size since the spot is seen more face-on, the maximum is when the spot passes the star’s meridian. The opposite happens when the spot moves over to the other side of the star. The spot has its maximum Doppler shift for;

Where l is the latitude and L is the longitude. Thus signatures from spots at higher latitudes will be restricted to spectral line centers, which will also occurring when the rotation axis is not perpendicular to the line of sight. If the spot is located at high latitude it is possible that it will always be seen, in which case the distortion in the line profile will move back and forth and only the amount of distortion will change.

Doppler imaging can also be made for changing chemical abundances across the stellar surface; these may not give rise to notches in the line profile since they can be brighter than the rest of the surface, instead producing a dip in the line profile.

Zeeman-Doppler imaging

The Zeeman-Doppler imaging is a variant of the Doppler imaging technique, by using circular and linear polarization information to see the small shifts in wavelength and profile shapes that occur when a magnetic field is present.

Binary stars

Another way to determine and see the extent of starspots is to study stars that are binaries. Then the problem with i =90° is reduced and the mapping of the stellar surface can be improved. When one of the stars passes in front of the other there will be an eclipse, and starspots on the eclipsed hemisphere will cause a distortion in the eclipse curve, revealing the location and size of the spots. This technique can be used for finding both dark (cool) and bright (hot) spots.

See also

References

- Vogt et al. (1987),"Doppler images of rotating stars using maximum entropy image reconstruction ", ApJ, 321, 496V

- Vogt, Steven S., & G. Donald Penros, "Doppler Imaging of spotted stars - Application to the RS Canum Venaticorum star HR 1099" in Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Symposium on the Renaissance in High-Resolution Spectroscopy - New Techniques, New Frontiers, Kona, HI, June 13–17, 1983 Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Publications (ISSN 0004-6280), vol. 95, Sept. 1983, p. 565-576.

- Strassmeier,( 2002 ),"Doppler images of starspots", AN, 323, 309S

- Korhonen et al. (2001), "The first close-up of the ``flip-flop phenomenon in a single star", A&A, 379L, 30K

- S.V.Berdyugina (2005), "Starspots: A Key to the Stellar Dynamo", Living Reviews in Solar Physics, vol. 2, no. 8

- K.G.Strassmeier (1997), "Aktive sterne. Laboratorien der solaren Astrophysik", Springer, ISBN 3-211-83005-7

- Gray, "The Observation and Analysis of Stellar Photospheres", 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521851866

- Collier Cameron et al., "Mapping starspots and magnetic fields on cool stars"