Dopamine transporter

The dopamine transporter (also dopamine active transporter, DAT, SLC6A3) is a membrane-spanning protein that pumps the neurotransmitter dopamine out of the synapse back into cytosol, from which other transporters sequester DA and NE into vesicles for storage and later release. Dopamine reuptake via DAT provides the primary mechanism through which dopamine is cleared from synapses, although there may be an exception in the prefrontal cortex, where evidence points to a possibly larger role of the norepinephrine transporter.[1]

DAT is implicated in a number of dopamine-related disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, clinical depression, and alcoholism. The gene that encodes the DAT protein is located on human chromosome 5, consists of 15 coding exons, and is roughly 64 kbp long. Evidence for the associations between DAT and dopamine related disorders has come from a type of genetic polymorphism, known as a VNTR, in the DAT gene (DAT1), which influences the amount of protein expressed.[2]

Function

DAT is an integral membrane protein that removes dopamine from the synaptic cleft and deposits it into surrounding cells, thus terminating the signal of the neurotransmitter. Dopamine underlies several aspects of cognition, including reward, and DAT facilitates regulation of that signal.[3]

Mechanism

DAT is a symporter that moves dopamine across the cell membrane by coupling the movement to the energetically-favorable movement of sodium ions moving from high to low concentration into the cell. DAT function requires the sequential binding and co-transport of two Na+ ions and one Cl− ion with the dopamine substrate. The driving force for DAT-mediated dopamine reuptake is the ion concentration gradient generated by the plasma membrane Na+/K+ ATPase.[4]

In the most widely accepted model for monoamine transporter function, sodium ions must bind to the extracellular domain of the transporter before dopamine can bind. Once dopamine binds, the protein undergoes a conformational change, which allows both sodium and dopamine to unbind on the intracellular side of the membrane.[5]

Studies using electrophysiology and radioactive-labeled dopamine have confirmed that the dopamine transporter is similar to other monoamine transporters in that one molecule of neurotransmitter can be transported across the membrane with one or two sodium ions. Chloride ions are also needed to prevent a buildup of positive charge. These studies have also shown that transport rate and direction is totally dependent on the sodium gradient.[6]

Because of the tight coupling of the membrane potential and the sodium gradient, activity-induced changes in membrane polarity can dramatically influence transport rates. In addition, the transporter may contribute to dopamine release when the neuron depolarizes.[6]

DAT–Cav coupling

Preliminary evidence suggests that the dopamine transporter couples to L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (particularly Cav1.2 and Cav1.3), which are expressed in virtually all dopamine neurons.[7] As a result of DAT–Cav coupling, DAT substrates that produce depolarizing currents through the transporter are able to open calcium channels that are coupled to the transporter, resulting in a calcium influx in dopamine neurons.[7] This calcium influx is believed to be induce CAMKII-mediated phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter as a downstream effect;[7] since DAT phosphorylation by CAMKII results in dopamine efflux in vivo, activation of transporter-coupled calcium channels is a potential mechanism by which certain drugs (e.g., amphetamine) trigger neurotransmitter release.[7]

Protein structure

The initial determination of the membrane topology of DAT was based upon hydrophobic sequence analysis and sequence similarities with the GABA transporter. These methods predicted twelve transmembrane domains (TMD) with a large extracellular loop between the third and fourth TMDs.[8] Further characterization of this protein used proteases, which digest proteins into smaller fragments, and glycosylation, which occurs only on extracellular loops, and largely verified the initial predictions of membrane topology.[9] The exact structure of the transporter was elucidated in 2013 by X-ray crystallography.[10]

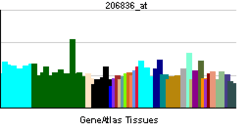

Location and distribution

Regional distribution of DAT has been found in areas of the brain with established dopaminergic circuitry including: nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical pathways.[11] The nuclei that make up these pathways have distinct patterns of expression. Gene expression patterns in the adult mouse show high expression in the substantia nigra pars compacta.[12]

DAT in the mesocortical pathway, labeled with radioactive antibodies, was found to be enriched in dendrites and cell bodies of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and ventral tegmental area. This pattern makes sense for a protein that regulates dopamine levels in the synapse.

Staining in the striatum and nucleus accumbens of the mesolimbic pathway was dense and heterogeneous. In the striatum, DAT is localized in the plasma membrane of axon terminals. Double immunocytochemistry demonstrated DAT colocalization with two other markers of nigrostriatal terminals, tyrosine hydroxylase and D2 dopamine receptors. The latter was thus demonstrated to be an autoreceptor on cells that release dopamine. TAAR1 is a presynaptic intracellular receptor that is also colocalized with DAT and which has the opposite effect of the D2 autoreceptor when activated; i.e., it internalizes dopamine transporters and induces efflux through reversed transporter function via PKA and PKC signaling.

Surprisingly, DAT was not identified within any synaptic active zones. These results suggest that striatal dopamine reuptake may occur outside of synaptic specializations once dopamine diffuses from the synaptic cleft.

In the substantia nigra, DAT is localized to axonal and dendritic (i.e., pre- and post-synaptic) plasma membranes.[13]

Within the perikarya of pars compacta neurons, DAT was localized primarily to rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi complex, and multivesicular bodies, identifying probable sites of synthesis, modification, transport, and degradation.[14]

Genetics and regulation

The gene for DAT, known as DAT1, is located on chromosome 5p15.[2] The protein encoding region of the gene is over 64 kb long and comprises 15 coding segments or exons.[15] This gene has a variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) at the 3’ end (rs28363170) and another in the intron 8 region.[16] Differences in the VNTR have been shown to affect the basal level of expression of the transporter; consequently, researchers have looked for associations with dopamine related disorders.[17]

Nurr1, a nuclear receptor that regulates many dopamine related genes, can bind the promoter region of this gene and induce expression.[18] This promoter may also be the target of the transcription factor Sp-1.

While transcription factors control which cells express DAT, functional regulation of this protein is largely accomplished by kinases. MAPK,[19] CAMKII,[20][21] PKA,[22] and PKC[21][23] can modulate the rate at which the transporter moves dopamine or cause the internalization of DAT. Co-localized TAAR1 is an important regulator of the dopamine transporter that, when activated, phosphorylates DAT through protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling.[22][24] Phosphorylation by either protein kinase can result in DAT internalization (non-competitive reuptake inhibition), but PKC-mediated phosphorylation alone induces reverse transporter function (dopamine efflux).[22][25] Dopamine autoreceptors also regulate DAT by directly opposing the effect of TAAR1 activation.[22] The human dopamine transporter, hDAT, has a high affinity zinc binding site that, upon binding Zn2+, facilitates amphetamine induced efflux and inhibits reuptake of hDAT substrates.[26]

Biological role and disorders

The rate at which DAT removes dopamine from the synapse can have a profound effect on the amount of dopamine in the cell. This is best evidenced by the severe cognitive deficits, motor abnormalities, and hyperactivity of mice with no dopamine transporters.[27] These characteristics have striking similarities to the symptoms of ADHD.

Differences in the functional VNTR have been identified as risk factors for bipolar disorder[28] and ADHD.[29] Data has emerged that suggests there is also an association with stronger withdrawal symptoms from alcoholism, although this is a point of controversy.[30][31] Interestingly, an allele of the DAT gene with normal protein levels is associated with non-smoking behavior and ease of quitting.[32] Additionally, male adolescents particularly those in high-risk families (ones marked by a disengaged mother and absence of maternal affection) who carry the 10-allele VNTR repeat show a statistically significant affinity for antisocial peers.[33][34]

Increased activity of DAT is associated with several different disorders, including clinical depression.[35]

Pharmacology

DAT is also the target of several "DAT-releasers" and “DAT-blockers” including amphetamine and cocaine. These chemicals inhibit the action of DAT and, to a lesser extent, the other monoamine transporters, but their effects are mediated by separate mechanisms.

Cocaine blocks DAT by binding directly to the transporter and reducing the rate of transport.[8] In contrast, amphetamine enters the presynaptic neuron directly through the neuronal membrane or through DAT, competing for reuptake with dopamine. Once inside, it binds to TAAR1 or enters synaptic vesicles through VMAT2. When amphetamine binds to TAAR1, it reduces the firing rate of the postsynaptic neuron and triggers protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling, resulting in DAT phosphorylation. Phosphorylated DAT then either operates in reverse or withdraws into the presynaptic neuron and ceases transport. When amphetamine enters the synaptic vesicles through VMAT2, dopamine is released into the cytosol.[22][36] Amphetamine also produces dopamine efflux through a second TAAR1-independent mechanism involving CAMKIIα-mediated phosphorylation of the transporter, which putatively arises from the activation of DAT-coupled L-type calcium channels by amphetamine.[7]

The dopaminergic mechanisms of each drug are believed to underlie the pleasurable feelings elicited by these substances.[3]

Interactions

Dopamine transporter has been shown to interact with:

Apart from these innate protein-protein interactions, recent studies demonstrated that viral proteins such as HIV-1 Tat protein interacts with the DAT[41][42] and this binding may alter the dopamine homeostasis in HIV positive individuals which is a contributing factor for the HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.[43]

See also

References

- ↑ Carboni E, Tanda GL, Frau R, Di Chiara G (1990). "Blockade of the noradrenaline carrier increases extracellular dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex: evidence that dopamine is taken up in vivo by noradrenergic terminals". J. Neurochem. 55 (3): 1067–70. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04599.x. PMID 2117046.

- 1 2 Vandenbergh DJ, Persico AM, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Li X, Jabs EW, Uhl GR (1992). "Human dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) maps to chromosome 5p15.3 and displays a VNTR". Genomics 14 (4): 1104–6. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80138-7. PMID 1478653.

- 1 2 Schultz W (1998). "Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons". J. Neurophysiol. 80 (1): 1–27. PMID 9658025.

- ↑ Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG (2003). "Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1038/nrn1008. PMID 12511858.

- ↑ Sonders MS, Zhu SJ, Zahniser NR, Kavanaugh MP, Amara SG (1997). "Multiple ionic conductances of the human dopamine transporter: the actions of dopamine and psychostimulants". J. Neurosci. 17 (3): 960–74. PMID 8994051.

- 1 2 Wheeler DD, Edwards AM, Chapman BM, Ondo JG (1993). "A model of the sodium dependence of dopamine uptake in rat striatal synaptosomes". Neurochem. Res. 18 (8): 927–936. doi:10.1007/BF00998279. PMID 8371835.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cameron KN, Solis E, Ruchala I, De Felice LJ, Eltit JM (2015). "Amphetamine activates calcium channels through dopamine transporter-mediated depolarization". Cell Calcium 58 (5): 457–66. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2015.06.013. PMID 26162812.

One example of interest is CaMKII, which has been well characterized as an effector of Ca2+ currents downstream of L-type Ca2+ channels [21,22]. Interestingly, DAT is a CaMKII substrate and phosphorylated DAT favors the reverse transport of dopamine [48,49], constituting a possible mechanism by which electrical activity and L-type Ca2+ channels may modulate DAT states and dopamine release. ... In summary, our results suggest that pharmacologically, S(+)AMPH is more potent than DA at activating hDAT-mediated depolarizing currents, leading to L-type Ca2+ channel activation, and the S(+)AMPH-induced current is more tightly coupled than DA to open L-type Ca2+ channels.

- 1 2 Kilty JE, Lorang D, Amara SG (1991). "Cloning and expression of a cocaine-sensitive rat dopamine transporter". Science 254 (5031): 578–579. doi:10.1126/science.1948035. PMID 1948035.

- ↑ Vaughan RA, Kuhar MJ (1996). "Dopamine transporter ligand binding domains. Structural and functional properties revealed by limited proteolysis". J. Biol. Chem. 271 (35): 21672–21680. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.35.21672. PMID 8702957.

- ↑ Penmatsa A, Wang KH, Gouaux E (2013). "X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism". Nature 503 (7474): 85–90. doi:10.1038/nature12533. PMC 3904663. PMID 24037379.

- ↑ Ciliax BJ, Drash GW, Staley JK, Haber S, Mobley CJ, Miller GW, Mufson EJ, Mash DC, Levey AI (1999). "Immunocytochemical localization of the dopamine transporter in human brain". J. Comp. Neurol. 409 (1): 38–56. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990621)409:1<38::AID-CNE4>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 10363710.

- ↑ Liu Z, Yan SF, Walker JR, Zwingman TA, Jiang T, Li J, Zhou Y (2007). "Study of gene function based on spatial co-expression in a high-resolution mouse brain atlas". BMC Syst Biol 1: 19. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-1-19. PMC 1863433. PMID 17437647.

- ↑ Nirenberg MJ, Vaughan RA, Uhl GR, Kuhar MJ, Pickel VM (1996). "The dopamine transporter is localized to dendritic and axonal plasma membranes of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons". J. Neurosci. 16 (2): 436–47. PMID 8551328.

- ↑ Hersch SM, Yi H, Heilman CJ, Edwards RH, Levey AI (1997). "Subcellular localization and molecular topology of the dopamine transporter in the striatum and substantia nigra". J. Comp. Neurol. 388 (2): 211–227. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<211::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 9368838.

- ↑ Kawarai T, Kawakami H, Yamamura Y, Nakamura S (1997). "Structure and organization of the gene encoding human dopamine transporter". Gene 195 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00131-5. PMID 9300814.

- ↑ Sano A, Kondoh K, Kakimoto Y, Kondo I (1993). "A 40-nucleotide repeat polymorphism in the human dopamine transporter gene". Hum. Genet. 91 (4): 405–6. doi:10.1007/BF00217369. PMID 8500798.

- ↑ Miller GM, Madras BK (2002). "Polymorphisms in the 3'-untranslated region of human and monkey dopamine transporter genes affect reporter gene expression". Mol. Psychiatry 7 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1038/sj/mp/4000921. PMID 11803445.

- ↑ Sacchetti P, Mitchell TR, Granneman JG, Bannon MJ (2001). "Nurr1 enhances transcription of the human dopamine transporter gene through a novel mechanism". J. Neurochem. 76 (5): 1565–1572. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00181.x. PMID 11238740.

- ↑ Morón JA, Zakharova I, Ferrer JV, Merrill GA, Hope B, Lafer EM, Lin ZC, Wang JB, Javitch JA, Galli A, Shippenberg TS (2003). "Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates dopamine transporter surface expression and dopamine transport capacity". J. Neurosci. 23 (24): 8480–8. PMID 13679416.

- ↑ Underhill SM, Wheeler DS, Li M, Watts SD, Ingram SL, Amara SG (July 2014). "Amphetamine modulates excitatory neurotransmission through endocytosis of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 in dopamine neurons". Neuron 83 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.043. PMC 4159050. PMID 25033183.

AMPH also increases intracellular calcium (Gnegy et al., 2004) that is associated with calmodulin/CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007) and modulation and trafficking of the DAT (Fog et al., 2006; Sakrikar et al., 2012).

- 1 2 Vaughan RA, Foster JD (September 2013). "Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 (9): 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005. PMC 3831354. PMID 23968642.

AMPH and METH also stimulate DA efflux, which is thought to be a crucial element in their addictive properties [80], although the mechanisms do not appear to be identical for each drug [81]. These processes are PKCβ– and CaMK–dependent [72, 82], and PKCβ knock-out mice display decreased AMPH-induced efflux that correlates with reduced AMPH-induced locomotion [72].

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miller GM (2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ↑ Pristupa ZB, McConkey F, Liu F, Man HY, Lee FJ, Wang YT, Niznik HB (1998). "Protein kinase-mediated bidirectional trafficking and functional regulation of the human dopamine transporter". Synapse 30 (1): 79–87. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<79::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9704884.

- ↑ Lindemann L, Ebeling M, Kratochwil NA, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Hoener MC (2005). "Trace amine-associated receptors form structurally and functionally distinct subfamilies of novel G protein-coupled receptors". Genomics 85 (3): 372–85. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.11.010. PMID 15718104.

- ↑ Maguire JJ, Parker WA, Foord SM, Bonner TI, Neubig RR, Davenport AP (2009). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXXII. Recommendations for trace amine receptor nomenclature". Pharmacol. Rev. 61 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1124/pr.109.001107. PMC 2830119. PMID 19325074.

- ↑ Scholze P, Nørregaard L, Singer EA, Freissmuth M, Gether U, Sitte HH (2002). "The role of zinc ions in reverse transport mediated by monoamine transporters". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (24): 21505–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112265200. PMID 11940571.

- ↑ Gainetdinov RR, Wetsel WC, Jones SR, Levin ED, Jaber M, Caron MG (1999). "Role of serotonin in the paradoxical calming effect of psychostimulants on hyperactivity". Science 283 (5400): 397–401. doi:10.1126/science.283.5400.397. PMID 9888856.

- ↑ Greenwood TA, Alexander M, Keck PE, McElroy S, Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Kelsoe JR (2001). "Evidence for linkage disequilibrium between the dopamine transporter and bipolar disorder". Am. J. Med. Genet. 105 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(2001)9999:9999<::AID-AJMG1161>3.0.CO;2-8. PMID 11304827.

- ↑ Yang B, Chan RC, Jing J, Li T, Sham P, Chen RY (2007). "A meta-analysis of association studies between the 10-repeat allele of a VNTR polymorphism in the 3'-UTR of dopamine transporter gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 144B (4): 541–550. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30453. PMID 17440978.

- ↑ Sander T, Harms H, Podschus J, Finckh U, Nickel B, Rolfs A, Rommelspacher H, Schmidt LG (1997). "Allelic association of a dopamine transporter gene polymorphism in alcohol dependence with withdrawal seizures or delirium". Biol. Psychiatry 41 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00044-3. PMID 9024952.

- ↑ Ueno S, Nakamura M, Mikami M, Kondoh K, Ishiguro H, Arinami T, Komiyama T, Mitsushio H, Sano A, Tanabe H (1999). "Identification of a novel polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene and the significant association with alcoholism". Mol. Psychiatry 4 (6): 552–7. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000562. PMID 10578237.

- ↑ Ueno S (2003). "Genetic polymorphisms of serotonin and dopamine transporters in mental disorders". J. Med. Invest. 50 (1-2): 25–31. PMID 12630565.

- ↑ Beaver KM, Wright JP, DeLisi M (2008). "Delinquent peer group formation: evidence of a gene x environment correlation". J Genet Psychol 169 (3): 227–44. doi:10.3200/GNTP.169.3.227-244. PMID 18788325.

- ↑ Florida State University (2 October 2008). "Specific Gene Found In Adolescent Men With Delinquent Peers". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ↑ Laasonen-Balk T, Kuikka J, Viinamäki H, Husso-Saastamoinen M, Lehtonen J, Tiihonen J (1999). "Striatal dopamine transporter density in major depression". Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 144 (3): 282–285. doi:10.1007/s002130051005. PMID 10435396.

- ↑ Eiden LE, Weihe E (2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216: 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

- ↑ Wersinger C, Sidhu A (2003). "Attenuation of dopamine transporter activity by alpha-synuclein". Neurosci. Lett. 340 (3): 189–92. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00097-1. PMID 12672538.

- ↑ Lee FJ, Liu F, Pristupa ZB, Niznik HB (2001). "Direct binding and functional coupling of alpha-synuclein to the dopamine transporters accelerate dopamine-induced apoptosis". FASEB J. 15 (6): 916–26. doi:10.1096/fj.00-0334com. PMID 11292651.

- ↑ Torres GE, Yao WD, Mohn AR, Quan H, Kim KM, Levey AI, Staudinger J, Caron MG (2001). "Functional interaction between monoamine plasma membrane transporters and the synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein PICK1". Neuron 30 (1): 121–34. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00267-7. PMID 11343649.

- ↑ Carneiro AM, Ingram SL, Beaulieu JM, Sweeney A, Amara SG, Thomas SM, Caron MG, Torres GE (2002). "The multiple LIM domain-containing adaptor protein Hic-5 synaptically colocalizes and interacts with the dopamine transporter". J. Neurosci. 22 (16): 7045–54. PMID 12177201.

- ↑ Midde, Narasimha M.; Yuan, Yaxia; Quizon, Pamela M.; Sun, Wei-Lun; Huang, Xiaoqin; Zhan, Chang-Guo; Zhu, Jun (2015-03-01). "Mutations at tyrosine 88, lysine 92 and tyrosine 470 of human dopamine transporter result in an attenuation of HIV-1 Tat-induced inhibition of dopamine transport". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology: The Official Journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 10 (1): 122–135. doi:10.1007/s11481-015-9583-3. ISSN 1557-1904. PMC 4388869. PMID 25604666.

- ↑ Midde, Narasimha M.; Huang, Xiaoqin; Gomez, Adrian M.; Booze, Rosemarie M.; Zhan, Chang-Guo; Zhu, Jun (2013-09-01). "Mutation of tyrosine 470 of human dopamine transporter is critical for HIV-1 Tat-induced inhibition of dopamine transport and transporter conformational transitions". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology: The Official Journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 8 (4): 975–987. doi:10.1007/s11481-013-9464-6. ISSN 1557-1904. PMC 3740080. PMID 23645138.

- ↑ Purohit, Vishnudutt; Rapaka, Rao; Shurtleff, David (2011-08-01). "Drugs of abuse, dopamine, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders/HIV-associated dementia". Molecular Neurobiology 44 (1): 102–110. doi:10.1007/s12035-011-8195-z. ISSN 1559-1182. PMID 21717292.

External links

- Dopamine transporter-related Associations, Experiments, Publications and Clinical Trials

- Dopamine Transporter at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||