Domain of a function

In mathematics, and more specifically in naive set theory, the domain of definition (or simply the domain) of a function is the set of "input" or argument values for which the function is defined. That is, the function provides an "output" or value for each member of the domain.[1] Conversely, the set of values the function takes on as output is termed the image of the function, which is sometimes also referred to as the range of the function.

For instance, the domain of cosine is the set of all real numbers, while the domain of the square root consists only of numbers greater than or equal to 0 (ignoring complex numbers in both cases). When the domain of a function is a subset of the real numbers, and the function is represented in an xy Cartesian coordinate system, the domain is represented on the x-axis.

Formal definition

Given a function f:X→Y, the set X is the domain of f; the set Y is the codomain of f. In the expression f(x), x is the argument and f(x) is the value. One can think of an argument as an input to the function, and the value as the output.

The image (sometimes called the range) of f is the set of all values assumed by f for all possible x; this is the set {f(x) | x ∈ X}. The image of f can be the same set as the codomain or it can be a proper subset of it. It is, in general, smaller than the codomain; it is the whole codomain if and only if f is a surjective function.

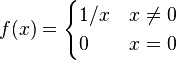

A well-defined function must map every element of its domain to an element of its codomain. For example, the function f defined by

has no value for f(0). Thus, the set of all real numbers, R, cannot be its domain. In cases like this, the function is either defined on R\{0} or the "gap is plugged" by explicitly defining f(0). If we extend the definition of f to

then f is defined for all real numbers, and its domain is  .

.

Any function can be restricted to a subset of its domain. The restriction of g : A → B to S, where S ⊆ A, is written g |S : S → B.

Natural domain

The natural domain of a function is the maximal set of values for which the function is defined, typically within the reals but sometimes among the integers or complex numbers. For instance the natural domain of square root is the non-negative reals when considered as a real number function. When considering a natural domain, the set of possible values of the function is typically called its range.[2]

Domain of a partial function

There are two distinct meanings in current mathematical usage for the notion of the domain of a partial function from X to Y, i.e. a function from a subset X' of X to Y. Most mathematicians, including recursion theorists, use the term "domain of f" for the set X' of all values x such that f(x) is defined. But some, particularly category theorists, consider the domain to be X, irrespective of whether f(x) exists for every x in X.

Category theory

In category theory one deals with morphisms instead of functions. Morphisms are arrows from one object to another. The domain of any morphism is the object from which an arrow starts. In this context, many set theoretic ideas about domains must be abandoned or at least formulated more abstractly. For example, the notion of restricting a morphism to a subset of its domain must be modified. See subobject for more.

Real and complex analysis

In real and complex analysis, a domain is an open connected subset of a real or complex vector space.

In partial differential equations, a domain is an open connected subset of the euclidean space Rn, where the problem is posed, i.e., where the unknown function(s) are defined.

More examples

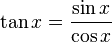

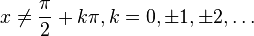

- As a partial function from the real numbers the function

is defined for all

is defined for all  .

. - If one defines the square root of a negative number x as the complex number z, with positive imaginary part, such that z2 = x, the function

is defined for all real numbers x.

is defined for all real numbers x. - Function

is defined for all

is defined for all

See also

- Bijection, injection and surjection

- Codomain

- Domain decomposition

- Effective domain

- Lipschitz domain

- Naive set theory

- Range (mathematics)

References

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||