Doggerland

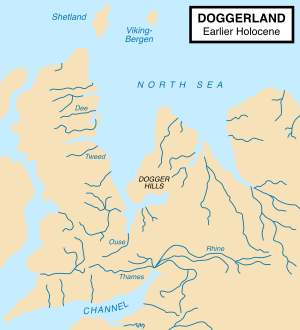

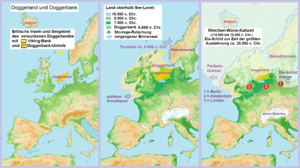

Doggerland was an area of land, now lying beneath the southern North Sea, that connected Great Britain to mainland Europe during and after the last Ice Age. It was then gradually flooded by rising sea levels around 6,500–6,200 BCE. Geological surveys have suggested that it stretched from Britain's east coast to the Netherlands and the western coasts of Germany and the peninsula of Jutland.[1] It was probably a rich habitat with human habitation in the Mesolithic period,[2] although rising sea levels gradually reduced it to low-lying islands before its final destruction, perhaps following a tsunami caused by the Storegga Slide.[3]

The archaeological potential of the area had first been discussed in the early 20th century, but interest intensified in 1931 when a commercial trawler operating between the sandbanks and shipping hazards of the Leman Bank and Ower Bank east of the Wash dragged up a barbed antler point that dated to a time when the area was tundra. Vessels have dragged up remains of mammoth, lion and other land animals, and small numbers of prehistoric tools and weapons.[4]

Formation

Until the middle Pleistocene, Britain was a peninsula off Europe, connected by a massive chalk anticline, the Weald–Artois Anticline across the Straits of Dover. During the Anglian glaciation, approximately 450,000 years ago, an ice sheet filled much of the North Sea, with a large proglacial lake in the southern part fed by the Rhine, Scheldt and Thames river systems. The catastrophic overflow of this lake carved a channel through the anticline, leading to the formation of the Channel River, which carried the combined Scheldt and Thames rivers into the Atlantic. It probably created the potential for Britain to become isolated from the continent during periods of high sea level, although some scientists argue that the final break did not occur until a second ice-dammed lake overflowed during the MIS8 or MIS6 glaciations, around 340,000 or 240,000 years ago.[5]

During the most recent glaciation, the Last Glacial Maximum that ended in this area around 18,000 years ago, the North Sea and almost all of the British Isles were covered with glacial ice and the sea level was about 120 m (390 ft) lower than it is today. After that the climate became warmer and during the Late Glacial Maximum much of the North Sea and English Channel was an expanse of low-lying tundra, around 12,000 BC extending to the modern northern point of Scotland.[6]

Evidence including the contours of the present seabed shows that after the first main Ice Age, the watershed between the North Sea and the English Channel extended east from East Anglia then south-east to the Hook of Holland rather than across the Strait of Dover and that the Seine, Thames, Meuse, Scheldt and Rhine joined and flowed along the English Channel dry bed as a wide slow river that flowed far before reaching the Atlantic Ocean.[2][6] At about 8000 BC the north-facing coastal area of Doggerland had a coastline of lagoons, saltmarshes, mudflats and beaches as well as inland streams, rivers, marshes and sometimes lakes. It may have been the richest hunting, fowling and fishing ground in Europe in the Mesolithic period.[2][7]

One big river system found by 3D seismic survey was the 'Shotton River', which drained the south-east part of the Dogger Bank hill area into the east end of the Outer Silver Pit lake. It is named after Birmingham geologist Frederick William Shotton.

Disappearance

As the thick ice sheet gradually melted away, at the end of the last glacial period of the current ice age, sea levels rose and the land began to rise and sink as an isostatic adjustment to the gradual removal of the huge weight of ice. Doggerland eventually became submerged beneath the North Sea, cutting off what was previously the British peninsula from the European mainland by around 6500 BC.[6] The Dogger Bank, an upland area of Doggerland, is believed to have remained as an island until at least 5000 BC.[6] Before it flooded completely, Doggerland was a wide undulating plain containing complex meandering river systems, with associated channels and lakes. Key stages are now believed to include the gradual evolution of a large tidal embayment between eastern England and Dogger Bank by 7000 BC and rapid sea level rise thereafter, leading to the Dogger Bank becoming an island and Great Britain being finally physically disconnected from the continent.[9]

A recent hypothesis is that much of the remaining coastal land, already much reduced in size from the original land area, was flooded by a megatsunami around 6200 BC caused by a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway known as the Storegga Slide. This theory suggests "that the Storegga Slide tsunami would have had a catastrophic impact on the contemporary coastal Mesolithic population. [...] Following the Storegga Slide tsunami, it appears, Britain finally became separated from the continent and in cultural terms, the Mesolithic there goes its own way."[9] A study published in 2014 suggested that the only remaining parts of Doggerland at the time of the Storegga Slide were low-lying islands, but supported the view that the area was abandoned at about the same time as the tsunamis.[3]

Another version is that the Storegga Slide tsunami devastated Doggerland but ebbed back into the sea and that later the bursting of Lake Agassiz released so much fresh water to the world ocean that sea level over about two years rose enough to permanently flood much of Doggerland and make Britain into an island.[10]

Discovery and investigation by archaeologists

By the late 19th century it was realized that what is now known as Doggerland had existed. For example, the H. G. Wells short story A Story of the Stone Age (1897) is set in "a time when one might have walked dryshod from France (as we call it now) to England, and when a broad and sluggish Thames flowed through its marshes to meet its father Rhine, flowing through a wide and level country that is under water in these latter days, and which we know by the name of the North Sea...Fifty thousand years ago it was, fifty thousand years if the reckoning of geologists is correct", though most of the action seems to occur in modern Surrey and Kent, but stretching out to Doggerland.[11]

The remains of plants brought to the surface from Dogger Bank had been studied as early as 1913 by paleobiologist Clement Reid and the remains of animals and worked flints from the Neolithic period had been found around the fringes of the area.[12] In his book The Antiquity of Man, published in 1915, anatomist Sir Arthur Keith had discussed the archaeological potential of the area.[12] In 1931, the trawler Colinda hauled up a lump of peat whilst fishing near the Ower Bank, 40 kilometres (25 mi) east of Norfolk. The peat was found to contain a barbed antler point, possibly used as a harpoon or fish spear, 220 millimetres (8.5 in) long, later identified to date from between 4,000 and 10,000 BCE, when the area was tundra.[2][7] The tool was exhibited in the Castle Museum in Norwich.[7]

Interest in the area was reinvigorated in the 1990s by the work of Professor Bryony Coles, who named the area "Doggerland" ("after the great banks in the southern North Sea"[7]) and produced a series of speculative maps of the area.[7][13] Although she recognised that the current relief of the southern North Sea seabed is not a sound guide to the topography of Doggerland,[13] the topography of the area has more recently begun to be reconstructed more authoritatively using seismic survey data obtained through petroleum exploration surveys.[14][15][16]

A skull fragment of a Neanderthal, dated at over 40,000 years old, was recovered from material dredged from the Middeldiep, a region of the North Sea some 16 kilometres (10 mi) off the coast of Zeeland, and was exhibited in Leiden in 2009.[17] In March 2010 it was reported that recognition of the potential archaeological importance of the area could affect the future development of offshore wind farms in the North Sea.[18]

In July 2012, the results of a fifteen-year study of Doggerland by the universities of St Andrews, Dundee, and Aberdeen, including artefacts and analysis of survey results, were displayed at the Royal Academy in London.[19] Richard Bates of St Andrews University said:[19]

"We have speculated for years on the lost land's existence from bones dredged by fishermen all over the North Sea, but it's only since working with oil companies in the last few years that we have been able to re-create what this lost land looked like....We have now been able to model its flora and fauna, build up a picture of the ancient people that lived there and begin to understand some of the dramatic events that subsequently changed the land, including the sea rising and a devastating tsunami."

In September 2015, archaeologists at the University of Bradford announced a major project to chart Doggerland in 3D, and to make extensive studies of DNA taken from deep sea core samples collected in the area. [20]

In popular culture

- The "Mammoth Journey" episode of the BBC television programme Walking with Beasts is partly set on the dry bed of the southern North Sea.

- The area featured in the "Britain's Drowned World" episode of the Channel 4 Time Team documentary series.[21]

- The first chapter of Edward Rutherfurd's novel Sarum describes the flooding of Doggerland.

- Science fiction author Stephen Baxter's Northland trilogy is set in an alternative timeline in which Doggerland (Northland in the books) is never inundated.

- The opening song of Ian Anderson's 2014 album, Homo Erraticus, is titled "Doggerland," and provides a first person narrative from the point of view of the prehistoric people who might have lived there.

- The Young Adult author Ted Garvin's "Doggerland" is set in Doggerland.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Doggerland Project", University of Exeter Department of Archaeology

- 1 2 3 4 Patterson, W, "Coastal Catastrophe" (paleoclimate research document), University of Saskatchewan

- 1 2 Rincon, Paul (1 May 2014). "Prehistoric North Sea 'Atlantis' hit by 5m tsunami". BBC News.

- ↑ Mihai, Andrei (February 5, 2015). "Doggerland – the land that connected Europe and the UK 8000 years ago". ZME Science. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ↑ Pettitt, Paul; White, Mark (2012). The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 98–102, 277. ISBN 978-0-415-67455-3.

- 1 2 3 4 University of Sussex, School of Life Sciences, C1119 Modern human evolution, Lecture 6, slide 23

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vincent Gaffney, "Global Warming and Lost Lands: Understanding the Effects of Sea Level Rise"

- ↑ Stride, A.H (January 1959). "On the origin of the Dogger Bank, in the North Sea". Geological magazine 96 (1): 33–34. doi:10.1017/S0016756800059197. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- 1 2 Bernhard Weninger et al., The catastrophic final flooding of Doggerland by the Storegga Slide tsunami, Documenta Praehistorica XXXV, 2008

- ↑ Britain's Stone Age Tsunami, Channel 4, 8 to 9 pm, Thursday 30 May 2013

- ↑ Online text

- 1 2 Keith, Arthur (15 August 2004). "3". The Antiquity of Man. Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. p. 41. ISBN 81-7041-977-8. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- 1 2 B.J. Coles. "Doggerland : a speculative survey (Doggerland : une prospection spéculative)", Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, ISSN 0079-497X, 1998, vol. 64, pp. 45–81 (3 p.1/4)

- ↑ Laura Spinney, "The lost world: Doggerland"

- ↑ Vincent Gaffney, Kenneth Thomson, Simon Fitch, Mapping Doggerland: The Mesolithic Landscapes of the Southern North Sea, University of Birmingham, 2007

- ↑ Vincent Gaffney, Simon Fitch, David Smith, Europe's Lost World: The rediscovery of Doggerland, University of Birmingham, 2009

- ↑ Palarch: Spectacular discovery of first-ever Dutch Neanderthal Fossil skull fragment unveiled by Minister Plasterk in National Museum of Antiquities, 15 June 2009

- ↑ Stone Age could complicate N.Sea wind farm plans, Reuters, 23 March 2010

- 1 2 BBC News, Hidden Doggerland underworld uncovered in North Sea, 3 July 2012. Accessed 4 July 2012

- ↑ Sarah Knapton (1 September 2015). "British Atlantis: archaeologists begin exploring lost world of Doggerland". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Heritage Action

Further reading

- The Rediscovery of Doggerland, by Vincent Gaffney, Simon Fitch & David Smith, Council for British Archaeology, 2009, ISBN 1-902771-77-X

- Doggerland: a Speculative Survey, by B.J. Coles, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 64 1998 pp 45–81.

- Mapping Doggerland: The Mesolithic Landscapes of the Southern North Sea, V. Gaffney, K. Thomson and S. Fitch (editors), 2007, Archaeopress.

- Discussed in depth in chapters 2–4 in Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History, Alistair Moffat, 2005, Thames & Hudson Inc. ISBN 978-0-500-05133-7

- Spinney, Laura (December 2012). Robert Clark (photog); Alexander Maleev (Illus.). "The Lost World of Doggerland". National Geographic 222 (6): 132–143. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doggerland. |

- "Hunting for DNA in Doggerland, an Ancient Land Beneath the North Sea", Elizabeth Preston, Wired, 27 November 2015

- "The moment Britain became an island", Megan Lane, BBC News, 15 February 2011

- "North Sea Paleolandscapes", Institute for Archaeology and Antiquity, University of Birmingham

- "North Sea Prehistory Research and Management Framework (NSPRMF) 2009", English Heritage, 2009

- "The Doggerland project", Professor Bryony Coles, University of Exeter. Includes hypothesised map of Doggerland in the early Holocene.

- CGI images (2 stills and a movie) of a Mesolithic camp beside the Shotton River

- "Das rekonstruierte Doggerland" ("Doggerland reconstructed"), computer generated images of a Doggerland landscape, 19 August 2008, Der Spiegel (German)

- "Hidden Doggerland underworld uncovered in North Sea", BBC News, 3 July 2012