Dyirbal language

| Dyirbal | |

|---|---|

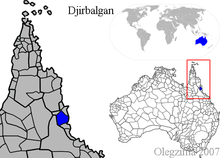

| Region | Northeast Queensland |

Native speakers |

15 (10 Girramay & 5 Dulgubarra Mamu) (2005)[1] to 28 Girramay (2006 census) |

|

Pama–Nyungan

| |

| Dialects |

Ngadjan

Waribarra Mamu

Dulgubarra Mamu

Jirrbal

Gulngay

Djirru

Girramay

Walmalbarra[2]

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

dbl |

| Glottolog |

dyir1250[3] |

| AIATSIS[1] |

Y123 |

| |

Dyirbal /ˈdʒɜːrbəl/[4] (also Djirubal) is an Australian Aboriginal language spoken in northeast Queensland by about 29 speakers of the Dyirbal tribe. It is a member of the small Dyirbalic branch of the Pama–Nyungan family. It possesses many outstanding features that have made it well known among linguists.

In the years since the Dyirbal grammar by Robert Dixon was published in 1972, Dyirbal has steadily gotten closer to extinction as younger community members have failed to learn it.[5]

Phonology

Dyirbal actually has only four places of articulation for the stop and nasals. This is fewer than most other Australian Aboriginal languages, which have six. This is because Dyirbal lacks the dental/alveolar/retroflex split typically found in these languages. Like the majority of Australian languages, it does not make a distinction between voiced consonants (such as b, d, g, etc.) and voiceless consonants (the corresponding p, t, and k, etc. respectively). Like Pinyin, standard Dyirbal orthography uses voiced consonants, which seem to be preferred by speakers of most Australian languages since the sounds (which can often be semi-voiced) are closer to English semi-voiced b, d, g than aspirated p, t, k.

The Dyirbal vowel system is typical of Australia, with three vowels: /i/, /a/ and /u/, though /u/ is realised as [o] in certain environments and /a/ can be realised as [e], also depending on the environment in which the phoneme appears. Thus the actual inventory of sounds is greater than the inventory of phonemes would suggest. Stress always falls on the first syllable of a word and usually on subsequent odd-numbered syllables except the ultima, which is always unstressed. The result of this is that consecutive stressed syllables do not occur.

| Peripheral | Laminal | Apical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Velar | Palatal | Alveolar | Retroflex | |

| Plosive | p | k | c | t | |

| Nasal | m | ŋ | ɲ | n | |

| Trill | ɲ | ||||

| Flap | ɽ | ||||

| Approximant | w | j | l | ||

Grammar

The language is best known for its system of noun classes, numbering four in total. They tend to be divided among the following semantic lines:

- I - most animate objects, men

- II - women, water, fire, violence, and exceptional animals[6]

- III - edible fruit and vegetables

- IV - miscellaneous (includes things not classifiable in the first three)

The class usually labelled "feminine" (II) inspired the title of George Lakoff's book Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. Some linguists distinguish between such systems of classification and the gendered division of items into the categories of "feminine", "masculine" and (sometimes) "neuter" that is found in, for example, many Indo-European languages.

Dyirbal shows a split-ergative system. Sentences with a first or second person pronoun have their verb arguments marked for case in a pattern that mimics nominative–accusative languages. That is, the first or second person pronoun appears in the least marked case when it is the subject (regardless of the transitivity of the verb), and in the most marked case when it is the direct object. Thus Dyirbal is morphologically accusative in the first and second persons, but morphologically ergative elsewhere; and it is still always syntactically ergative.

Taboo

There used to be in place a highly complex taboo system in Dyirbal culture. A speaker was completely forbidden from speaking with his/her mother-in-law, child-in-law, father's sister's child or mother's brother's child, and from approaching or looking directly at these people.[7] A person is forbidden from speaking with their cross-cousin of the opposite sex due to the fact that those relatives are of the section from which an individual must marry, but are too close of kin to choose as a spouse so the avoidance might be present on the grounds of indicating who is sexually unavailable.[7]

Furthermore, because marriage typically takes place a generation above or below, the cross-cousin of the opposite sex often is a potential mother-in-law or father-in-law.[8] In addition, when within hearing range of taboo relatives a person was required to use a specialized and complex form of the language with essentially the same phonemes and grammar, but with a lexicon that shared no words with the non-taboo language except for four lexical items referring to grandparents on the mother and father’s side.[9]

The taboo relationship is reciprocal. Thus, an individual is not allowed to speak with one’s own mother-in-law and it is equally taboo for the mother-in-law to speak with her son-in-law.[7] This relationship is also prevalent among both genders such that a daughter-in-law is forbidden to speak to directly or approach her father-in-law and vice versa. This taboo exists, although it is not as strongly enforced, between members of the same sex such that a male individual should use the respectful style of speech in the presence of his father-in-law, but the father-in-law can decide whether or not to use the everyday style of speech or the respectful style in the presence of his son-in-law.[7]

The specialized and complex form of the language is known as the Dyalŋuy and is used in the presence of the taboo relatives whereas a form referred to in most dialects as Guwal is used in all other circumstances.[7] The Dyalŋuy has one fourth of the amount of lexical items as the everyday language which reduces the semantic content in actual communication in the presence of a taboo relative.[10] For example, in Dyalŋuy the verb 'to ask' is [baŋarrmba-l]. In Guwal, 'to ask' is [ŋanba-l], 'to invite someone over' is [yumba-l], 'to invite someone to accompany one' is [bunma-l] and 'to keep asking after having already been told' is [gunji-y]. There are no correspondences to the other 3 verbs of Guwal in Dyalŋuy.[9]

To get around this limitation, Dyirbal speakers use many syntactic and semantic tricks to make do with a minimal vocabulary which reveals a lot to linguists about the semantic nature of Dyirbal. For example, Guwal makes use of lexical causatives, such as transitive bana- "break" and intransitive gaynyja- "break" (similar to English be dead/kill, lie/lay). Since Dyirbal has fewer lexemes, a morpheme -rri- is used as an intransitive derivational suffix. Thus the Dyalŋguy equivalents of the two words above are transitive yuwa and intransitive yuwa-rri-.[11]

The lexical items found in Dyalŋuy are mainly derived from three sources: “borrowings from the everyday register of neighboring dialects or languages, the creation of new [Dyalŋuy] forms by phonological deformation of lexemes from the language's own everyday style, and the borrowing of terms that were already in the [Dyalŋuy] style of a neighboring language or dialect.”[12]

An example of borrowing between dialects is the word for sun in the Yidin and Ngadyan dialects. In Yidin, the Guwal style word for sun is [buŋan], and this same word is also the Dyalŋuy style of the word for sun in the Ngadyan dialect.[7] It is hypothesized that children of Dyirbal tribes were expected to acquire the Dyalŋuy speech style years following their acquisition of the everyday speech style from their cross cousins who would speak in Dyalŋuy in their presence. By the onset of puberty, the child probably spoke Dyalŋuy fluently and was able to use it in the appropriate contexts.[8] This phenomenon, commonly called mother-in-law languages, was common in indigenous Australian languages. It existed until about 1930, when the taboo system fell out of use.

Notes

- 1 2 Dyirbal at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge University Press. p. xxxiii.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Dyirbal". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ Schmidt, A: "Young People's Dyirbal: An Example of Language Death from Australia" (Cambridge University Press, 1985)

- ↑ Lakoff, George (1990). Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. University of Chicago Press. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dixon, R. M. W. (1972). The Dyirbal language of north Queensland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- 1 2 Dixon, R. M. W. (1989). The Dyirbal kinship system. Oceania , 59(4), 245-268.

- 1 2 Dixon, R. M. W. (1990). The origin of "mother-in-law vocabulary" in two Australian languages. Anthropological Linguistics , 32(1/2), 1-56.

- ↑ Silverstein, M. (1976). Shifters, linguistic categories, and cultural description. In K. H. Basso & H. A. Selby (Eds.), Meaning in Anthropology (pp. 11-55). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- ↑ Dixon, R.M.W. (2000). "A Typology of Causatives: Form, Syntax, and Meaning". In Dixon, R.M.W. & Aikhenvald, Alexendra Y. Changing Valency: Case Studies in Transitivity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–40

- ↑ Evans, N. (2003). Context, culture, and structuration in the languages of Australia. Annual Review of Anthropology, 32, 13-40.

References

- Dixon, R.M.W. (1972). The Dyirbal language of North Queensland. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

External links

- Lecture notes on Dyirbal illustrating mother-in-law language

- Bibliography of Dyirbal people and language resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Bibliography of Girramay people and language resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Bibliography of the Gulngay people and language resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||